THE EXTENT AND LIMIT OF NEW ORLEANS — ITS WARDS, DISTRICTS, AND OTHER SUB-DIVISIONS — THE FOUNDING OF THE CITY — A BRIEF REVIEW OF ITS EARLY HISTORY.

While all the country north of the Tennessee river is locked in ice: its trees leafless and its

homes stormed by fierce arctic winds, New Orleans smiles through the green of orange and

magnolia trees. Her gardens are bright and odorous with flowers; the streets are filled with

loungers and sight-seers; all the open-air resorts are crowded; there is a busy hum of gaiety

and music and laughter everywhere.

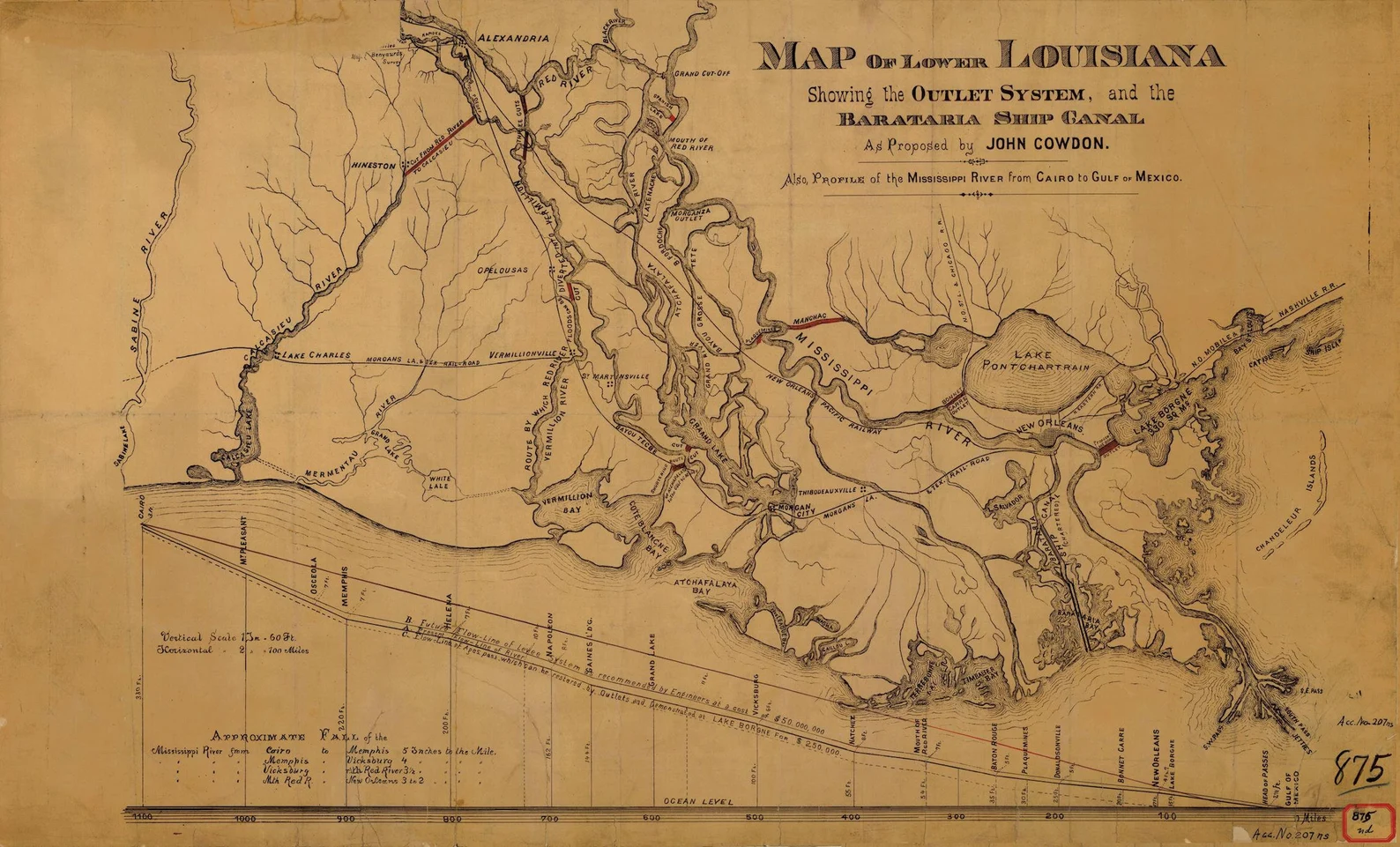

The city boasts three waterside resorts. Each has a hotel, a theatre, a fine restaurant. All

of them are on Lake Pontchartrain, only five or six miles from the heart of the city, by steam

cars running at short intervals. To him who has lived among blizzards and hailstorms, it must

be a sensation to dine upon an open balcony in January, to see roses blooming in the garden, to

breathe the soft south wind fanned from the Gulf of Mexico, and feel that luxuriousness peculiar

to tropical latitudes. He can take his choice of the West End, Spanish Fort and Milneburg, at

any of which points he can get an elegant repast. There is the Jockey Club with its races, the

bayous and their aquatic sports, the base-ball parks, the river-side resorts with beer and music.

In town are many restaurants, theatres, concert halls and saloons, where the stranger can

spend his evening pleasantly. Indeed, one must be strangely hard to please who, coming from

the bleak and wintry North, cannot find sufficient enjoyment rambling about the bright and

crowded streets, peeping into places of amusement and tasting the luxury of the wondrous

climate of New Orleans.

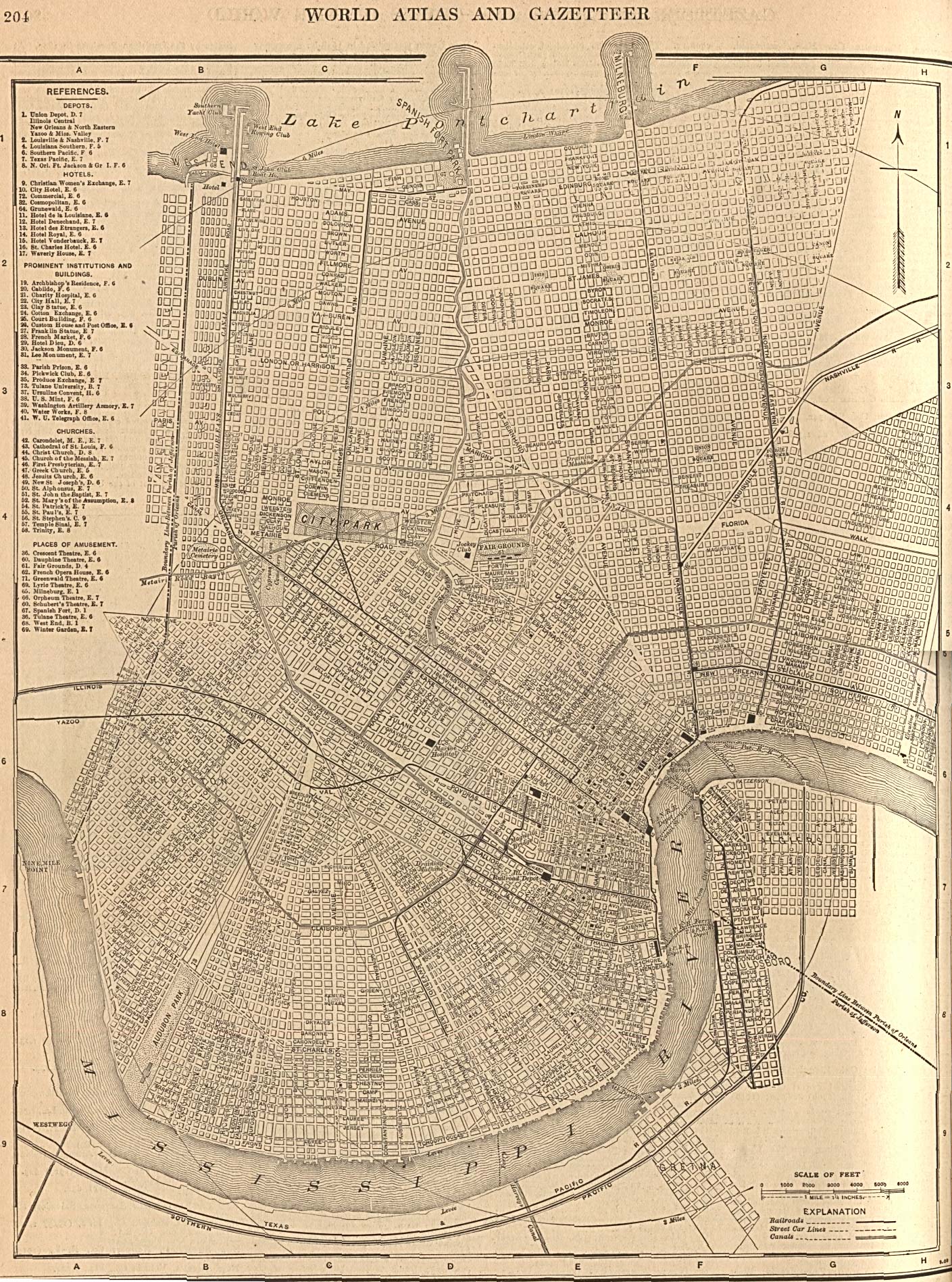

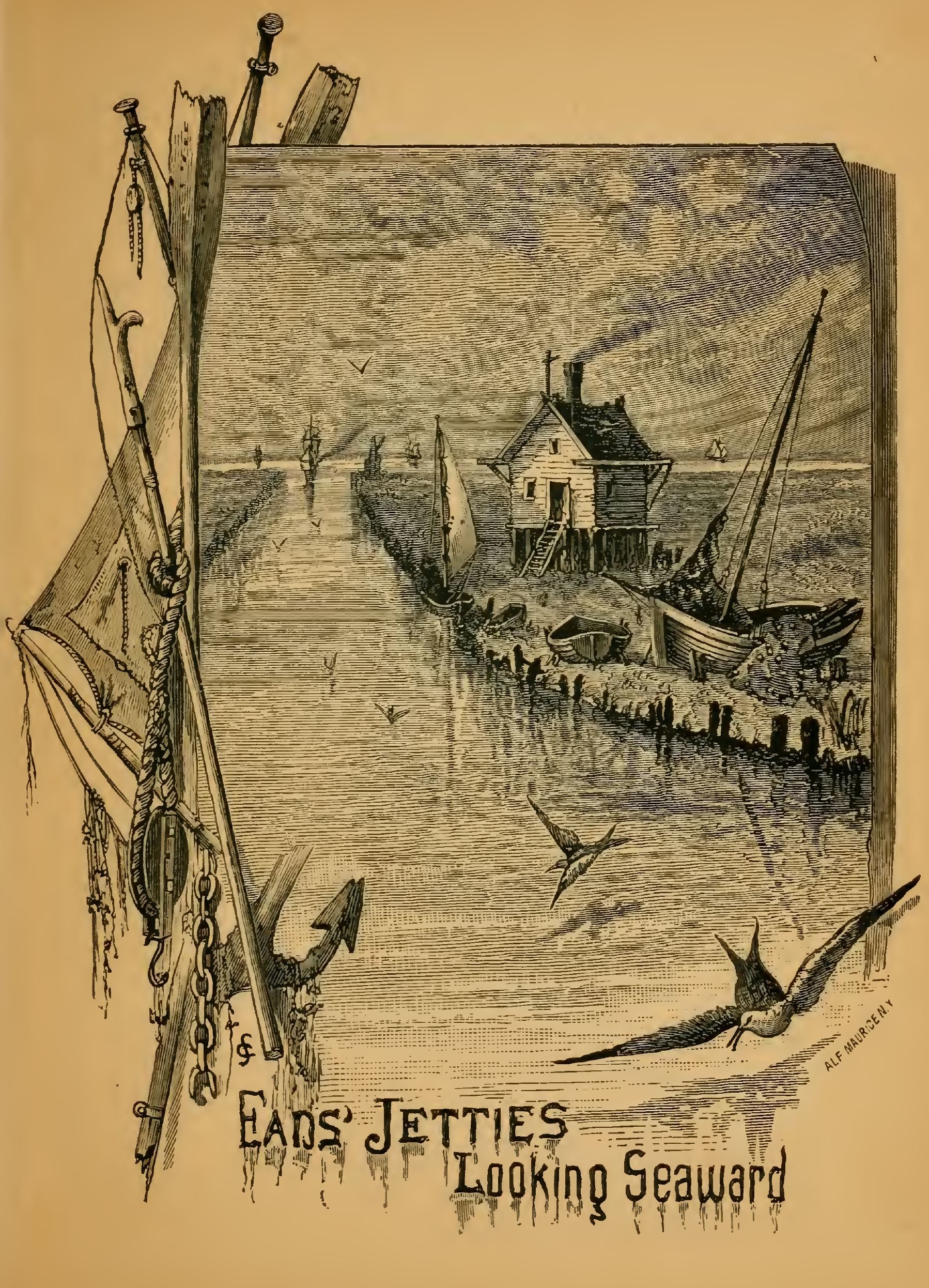

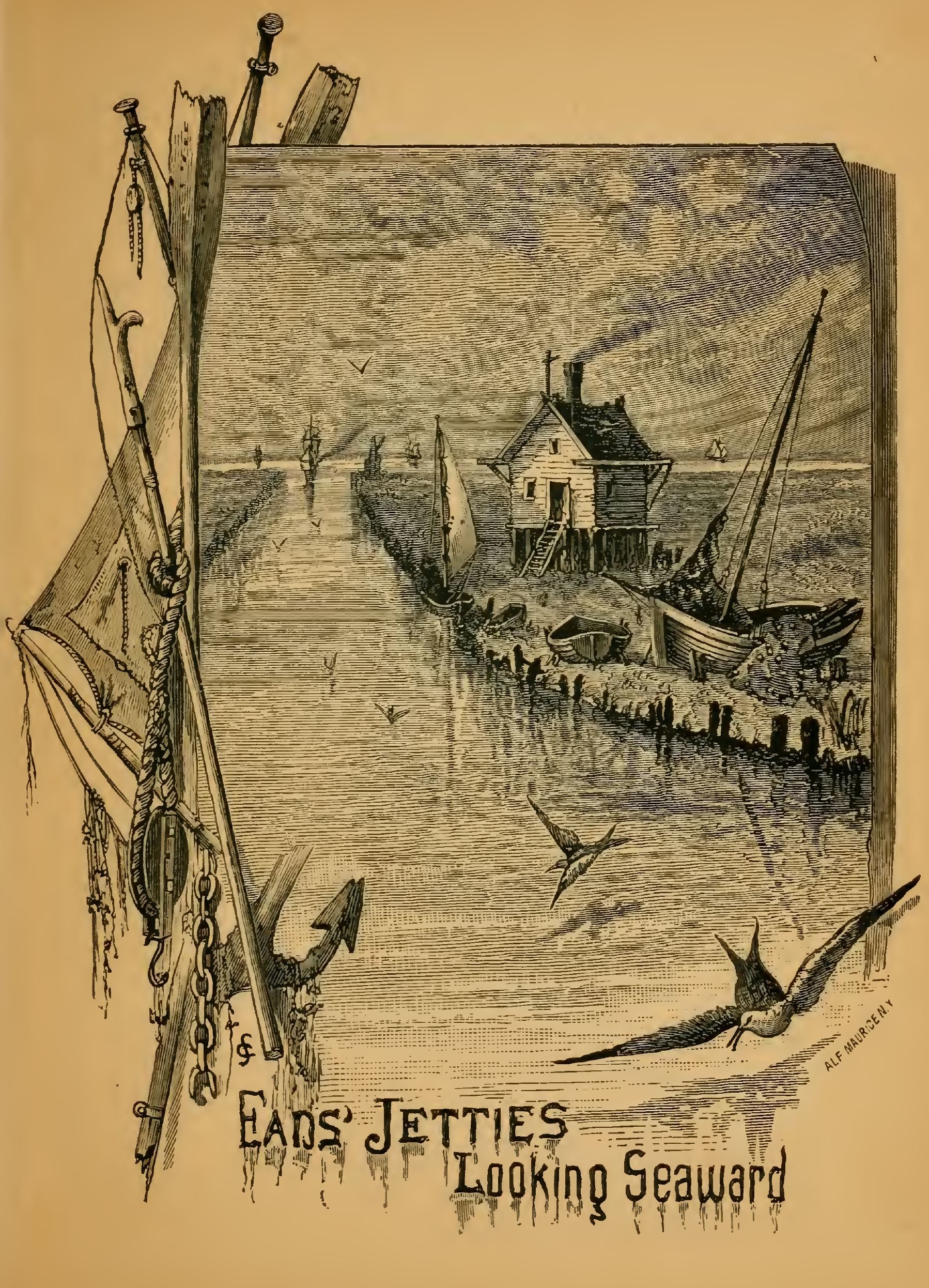

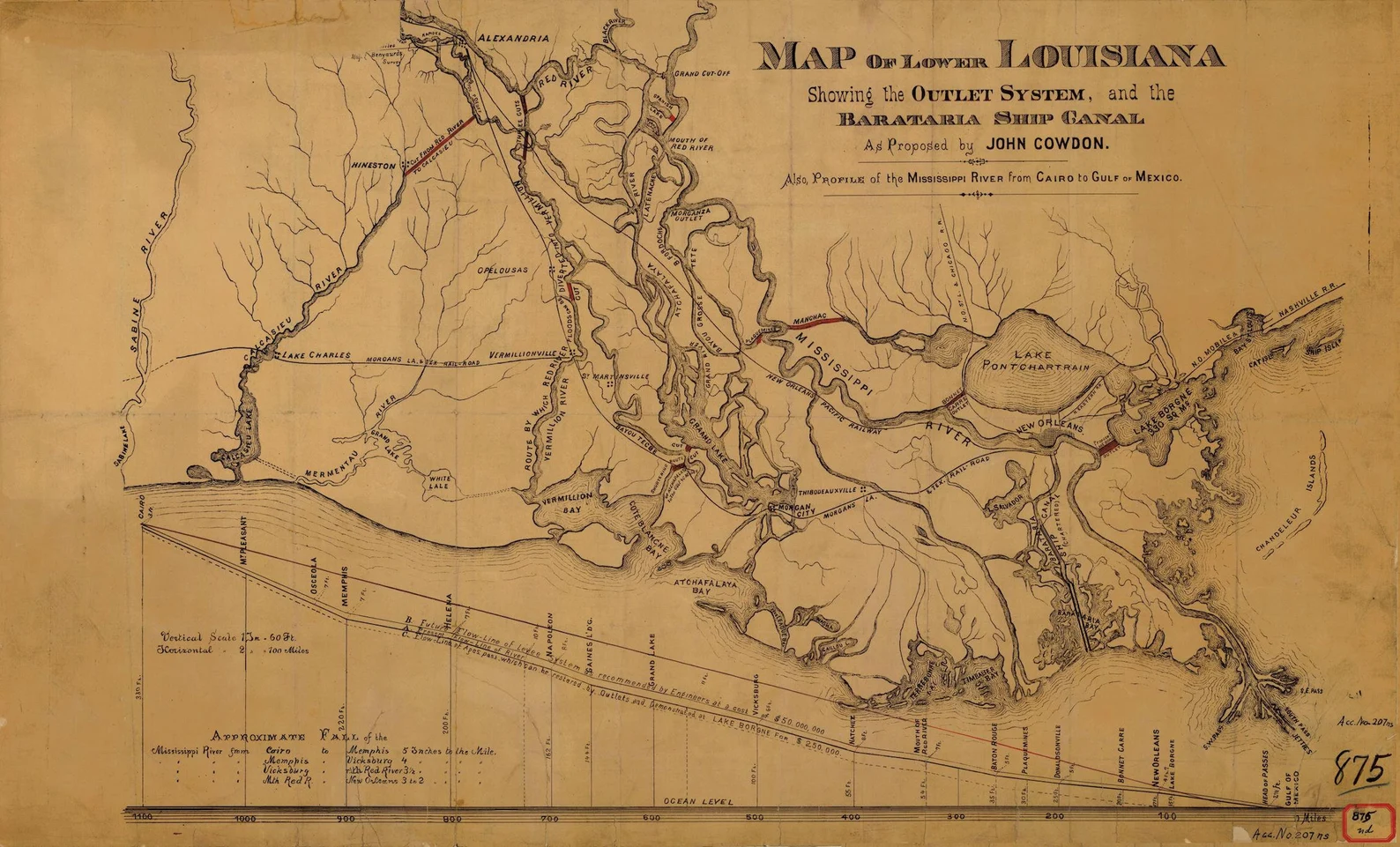

The city is situated on the left or east bank of the Mississippi, 107 miles from its mouth. A

small portion — the fifteenth ward, generally styled “Algiers” — is on the west bank, but the

great bulk of it, with nineteen-twentieths of its population, is east of the river.

The Mississippi here is 1,500 to 3,000 feet in width, being much narrower than above. However, it makes up in depth, which here ranges from 60 to 250 feet, and enables the largest vessels

to land at the bank or wharf. The speed of the current varies greatly, being 5 miles an hour

during high water, at other periods very slow. The current, moreover, is treacherous, and in

many places the river runs up-stream. Even when the upper current is moving towards the

Gulf, an under-current runs in a different direction. Notwithstanding the power of the river, it

is affected by the Gulf, and the latter’s tides are felt at New Orleans. Salt water often forces

its way up the Mississippi, making the river water, on which many depend, unfit to drink; salt

water fish are often caught in the river at and above New Orleans, and sharks over seven feet long.

The tendency of the Mississippi, at the city, is to move westward. This it does, by

depositing its alluvium on the east or New Orleans bank, and washing away the other bank,

causing large cavings. This movement is rapid, averaging 15 feet a year. It is always adding

new squares and streets to the front of New Orleans, which is known as “the batture.” When

the city was founded, the Custom-house which stood 160 years ago where it stands to-day, was

on the river bank. Now it is three squares inland. At the foot of St. Joseph street most

batture has been made, the river having travelled westward 1800 feet in a century and a half.

What is now the east bank was then the west bank. During that period the Mississippi has filled up

slowly but surely, its own channel — which is now well built up — and has, at the same time,

carved out an entirely new channel for itself.

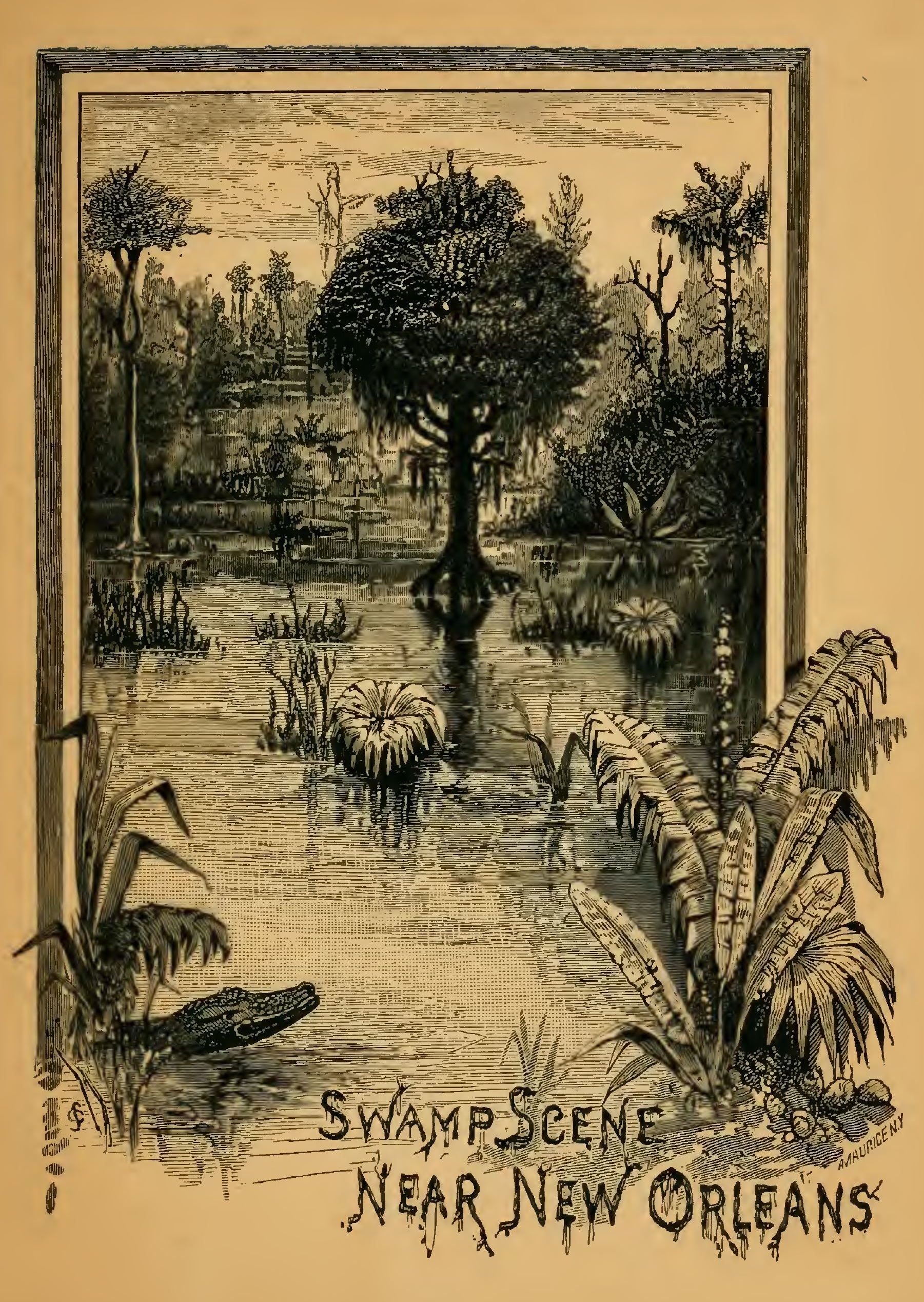

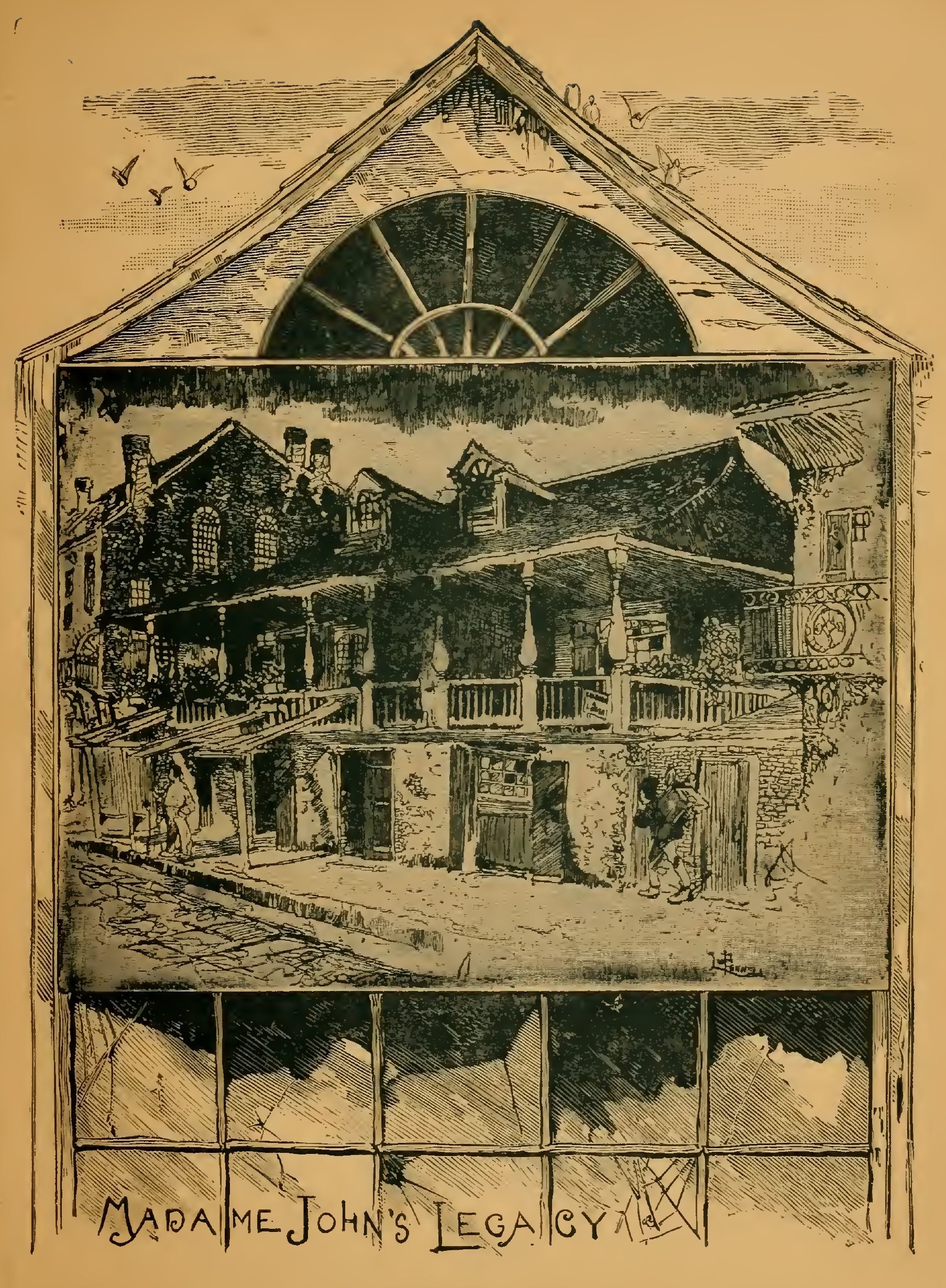

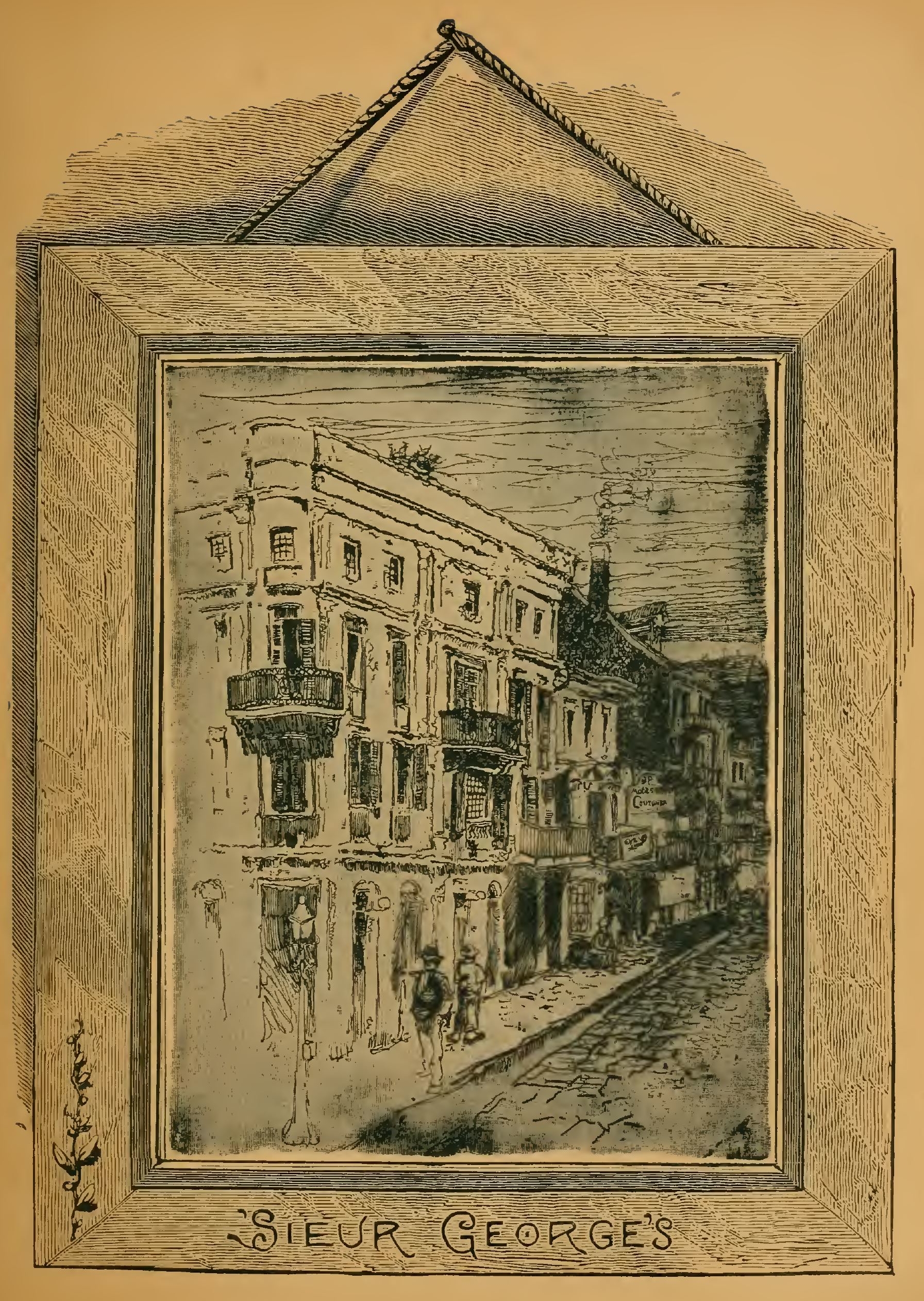

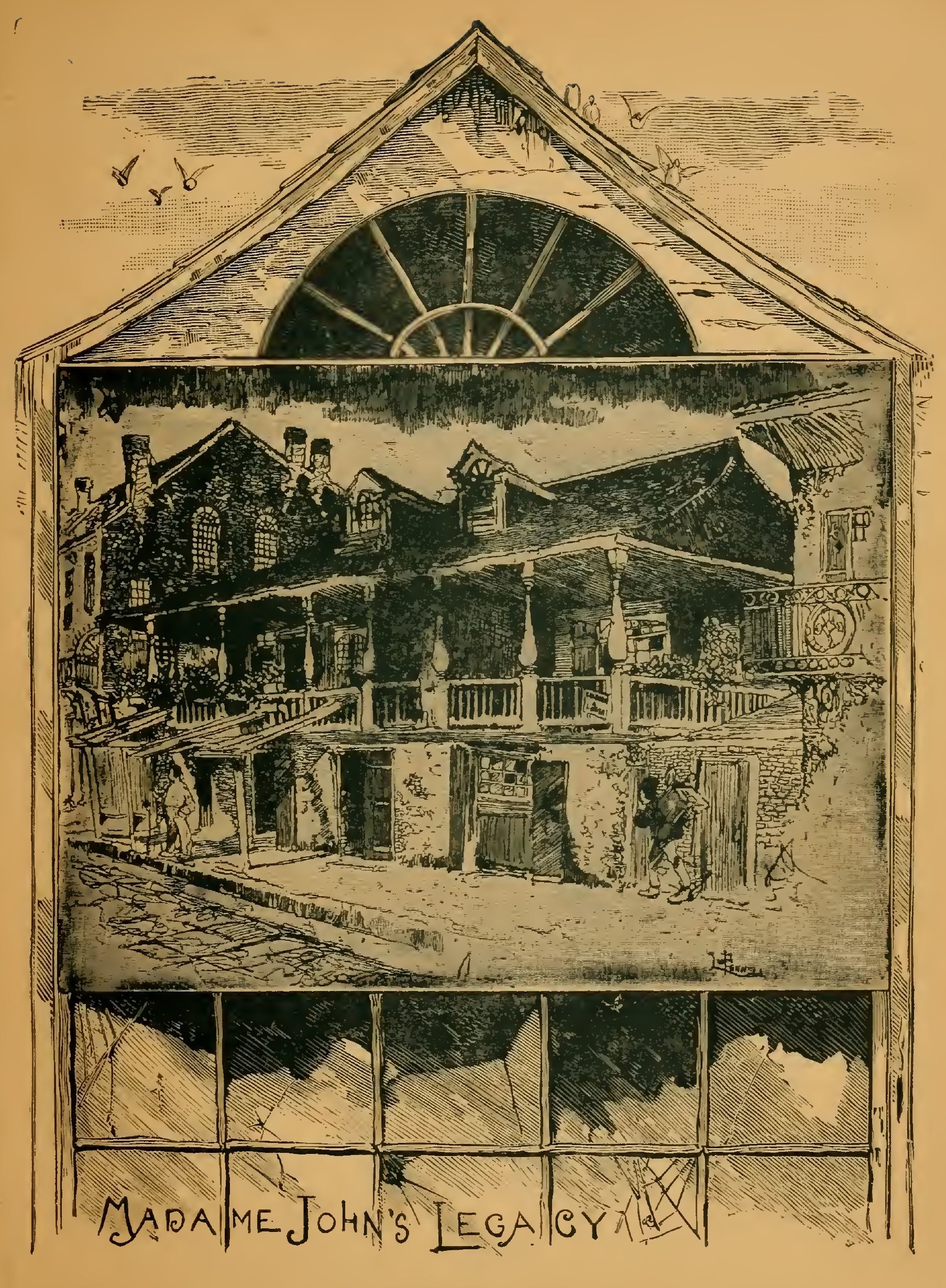

“New Orleans is specially interesting among the cities of the United States,” remarks

the British Encyclopædia “from the picturesqueness of its older sections, and the languages, tastes

and customs of a large portion of Its people. Its history is as sombre and unique as the dark

wet cypress forest, draped in long pendant Spanish moss, which once occupied its site and

which still encircles its horizon.”

It was founded in 1718 by Jean Baptiste Lemoyne de Bienville, a French Canadian, Governor

of the French colony which had been planted nineteen years earlier at Biloxi, on Mississippi

Sound. A few years after its founding when it was still but little more than a squalid village of

deported galley slaves, trappers and gold hunters, it was made the capital of that vast Louisiana, which loosely comprised the whole Mississippi Valley. The names remaining in vogue

in that portion of the city still distinguished as le vieux carré, or the old French quarter, preserve

an interesting record of these humble beginnings. The memory of the French dominion is

retained in the titles and foreign aspects of Toulouse, Orleans, Du Maine, Conti, Dauphiné and

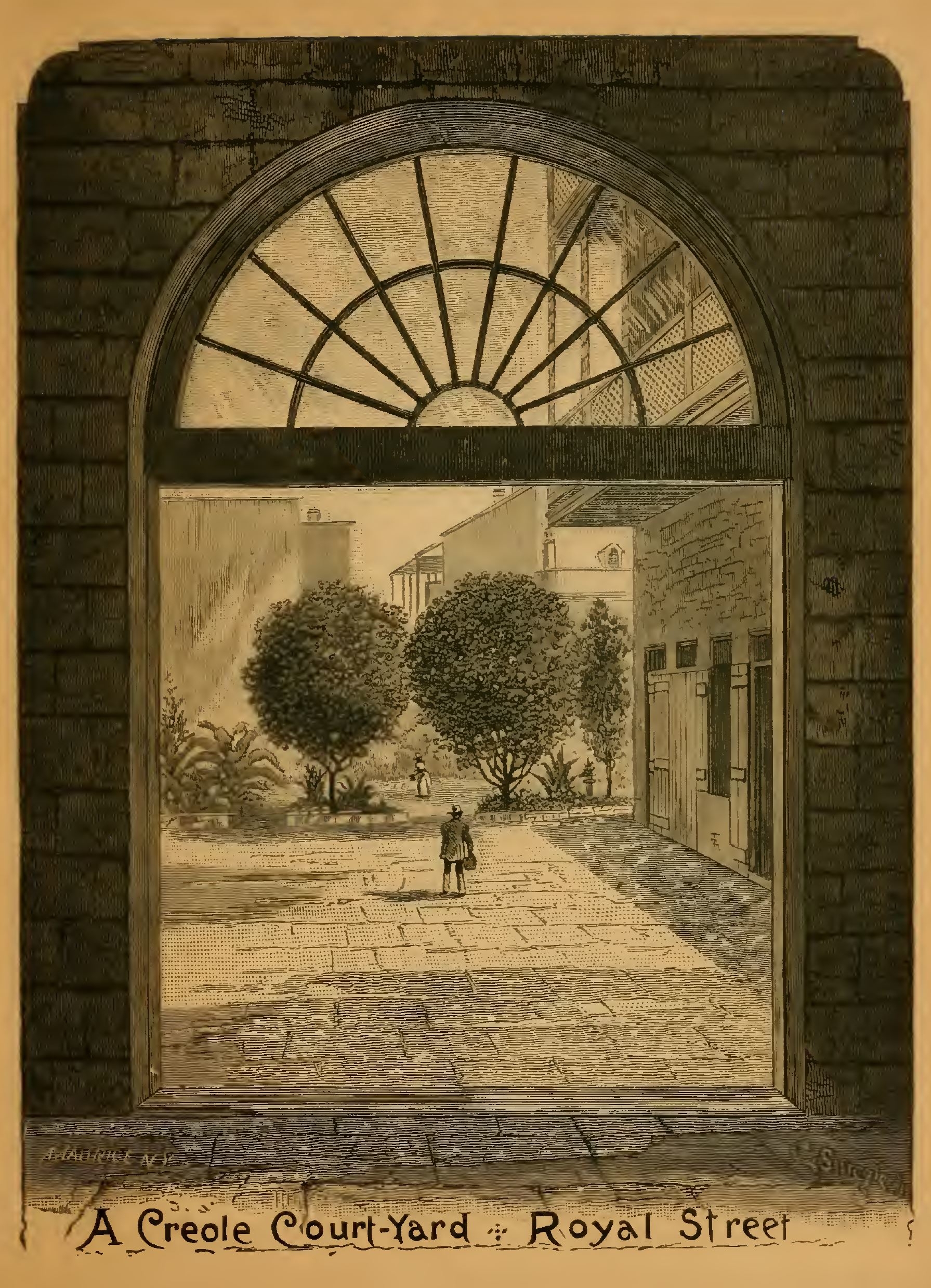

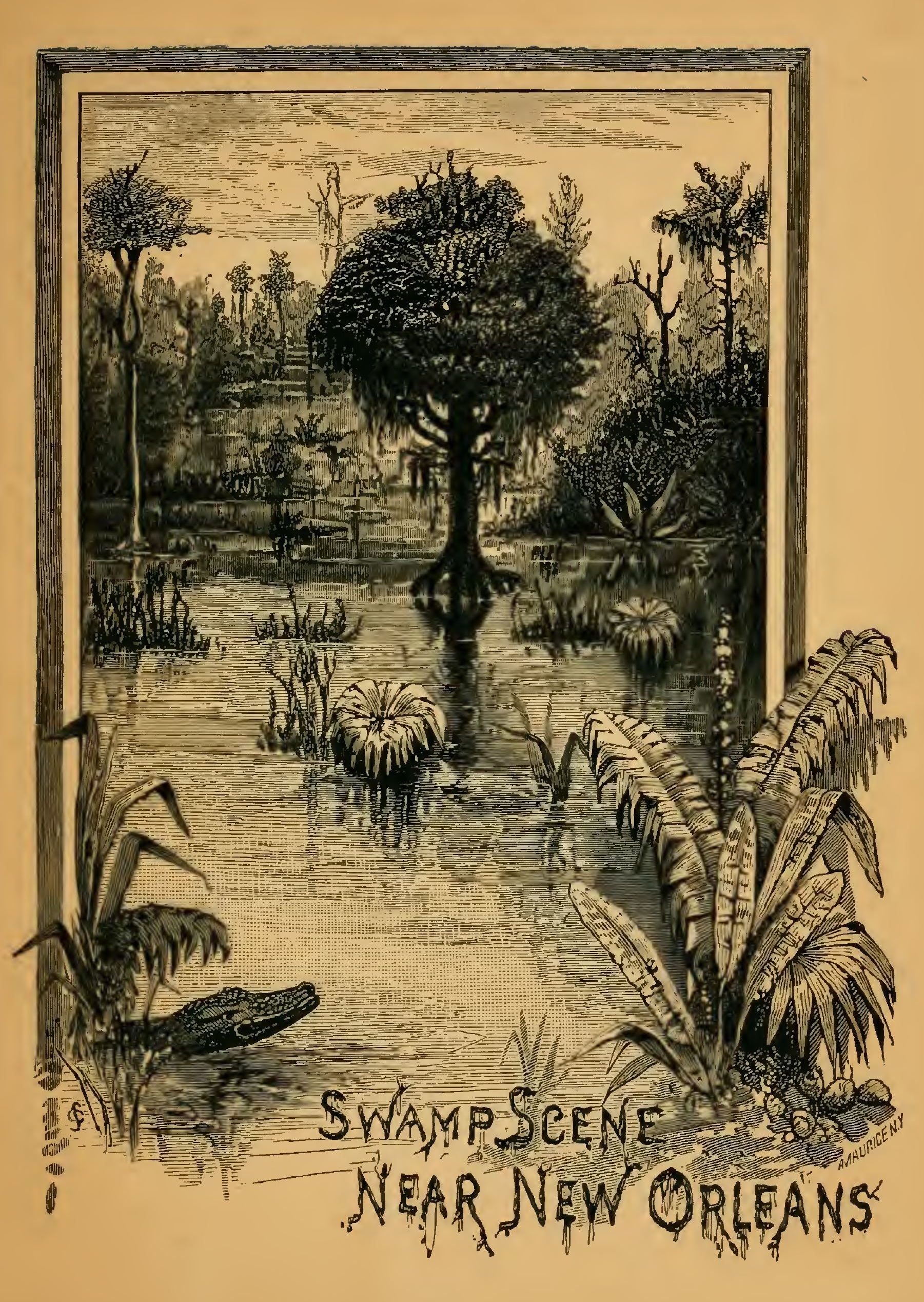

Chartres streets; while the sovereignty of Spain is even more distinctly traceable in the stuccoed

walls and iron lattices, huge locks and hinges, arches and gratings, balconies and jalousies,

corrugated roofs of tiles, dim corridors and inner courts, brightened with portierés, urns and

basins, statues half hid in roses and vines, and musical with sounds of trickling water. There

are streets named for the Spanish Governors, Unzaga. Galvez. Miro, Salcedo, Casa Calva and

Carondelet.

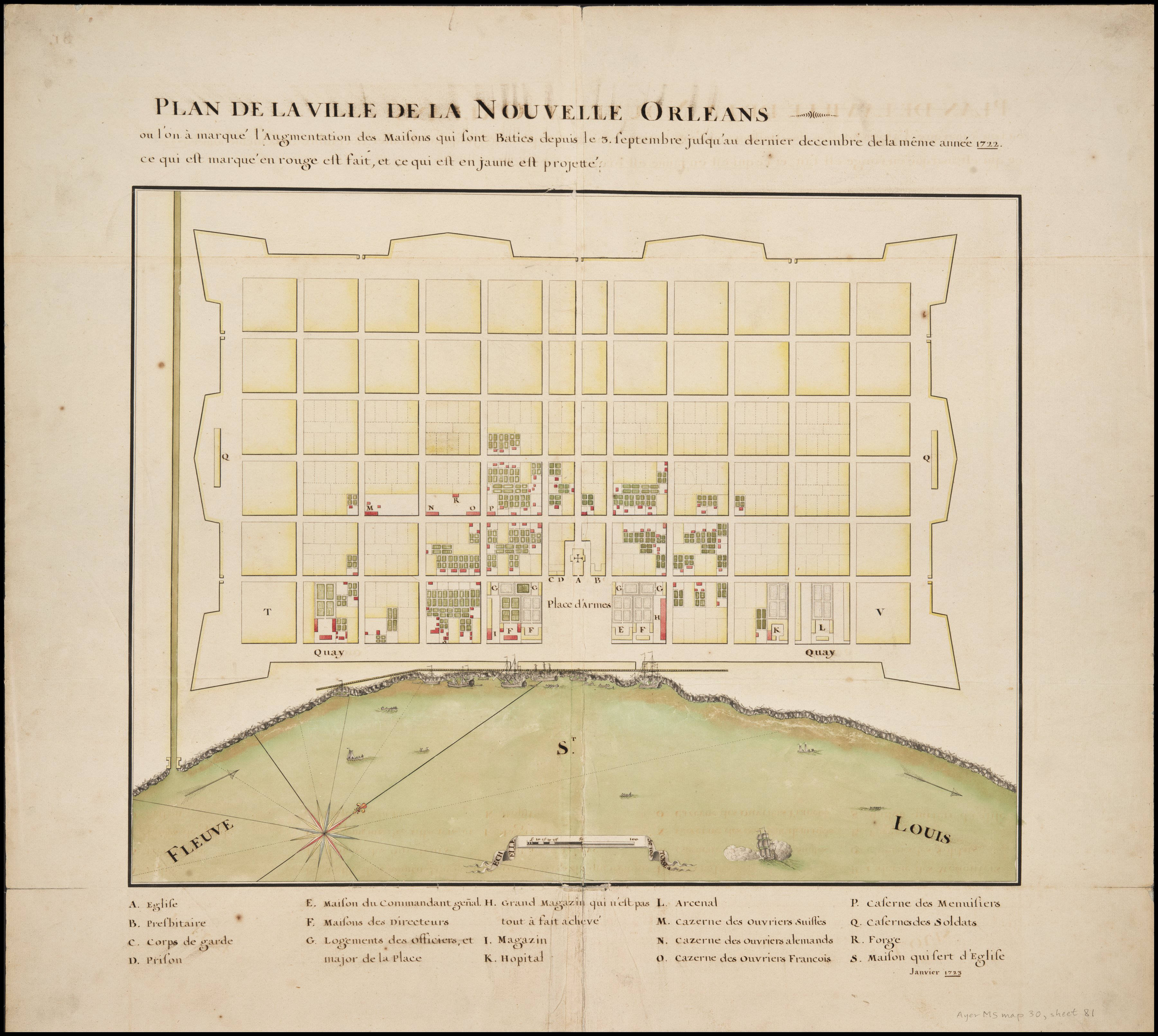

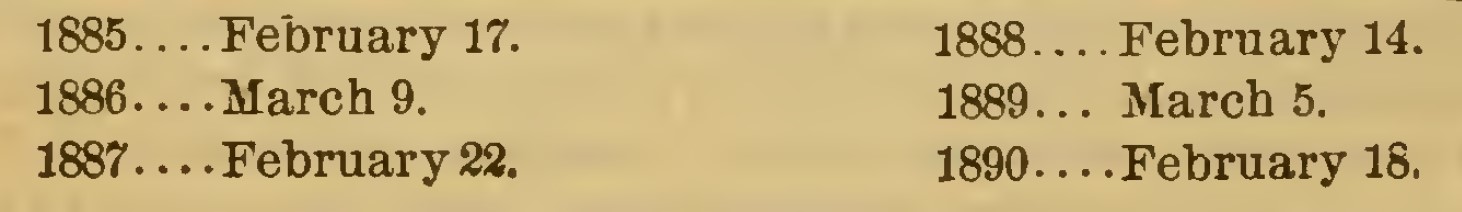

New Orleans. 1723.

The site of New Orleans was selected by Bienville as the highest point on the river bank and

consequently safe from overflow. The second year of its occupation, however, the entire town

was submerged, and it was found necessary to construct a dyke around it to protect it against

inundation. This dyke was the beginning of the immense system of levées which have cost the

people of the Lower Mississippi Valley over $150,000,000 to erect and maintain. The site selected

by Bienville for the city was deemed specially favorable, first on account of its height — it was

ten feet above the level of the ocean — and secondly, on account of a bayou which ran just back

of the town to Lake Pontchartrain, thus giving the city communication with the Gulf, otherwise

than by the river whose strong current at high flood rendered it difficult of ascent. It did not

prove to be so favorable as it had appeared at first sight, being covered by a noisome and

almost impenetrable cypress swamp, and subject to frequent if not annual overflow. Its distance from the mouth of the river was also a great disadvantage. Bayou St. John, known to the

Indians as Choupich (muddy), and Bayou Sauvage, afterward Gentilly, navigable to small seagoing vessels to within a mile of the Mississippi’s bank, led by a short course to the open waters of the lake and thence to the Gulf. Here, in 1718, Bienville landed a detachment of twenty-five

convicts or galley slaves, twenty-five carpenters and a few voyageurs from the Illinois Country

(Canadians) to make a clearing and erect the necessary huts for the new city which he proposed

to found, and which he named in honor of his Highness, the Prince Regent of France, Louis

Philippe, Duke d’Orléans, one of the greatest roués and scoundrels that ever lived.

The original city, as laid off by Bienville, comprised eleveu squares front on the river,

running from Customhouse street (rue de la Douane) to Barracks street (rue des Quartiers),

and five squares back from levée street (rue de la levée) to Burgundy (rue de la Bourgogne). These limits constituted for many years the boundaries of New Orleans. During

the early French days, houses were built back of this, along the road running towards

the lake and Bayou St. John. Plantations were established on the river bank, both

above and below the city. When the city was transferred from Spain to France, and thence

to the United States, the great bulk of the population still lived in the old quarters. The

Americans, however, began to establish themselves above on what was of old the Jesuits’

plantation, building up a new town, which became known as the faubourg St. Mary or

Sainte Marie. At the lower end of town, another suburb was laid out, known as faubourg

Marigny. This made New Orleans a perfect crescent in shape, for the river just in front

of the city bends gracefully in the form of a half moon. To this circumstance is due the title of

“Crescent City,” bestowed upon New Orleans fifty years ago, and which, although very applicable then, is ridiculous to-day. The city has spread up stream, following the bank of the river, annexing innumerable suburban towns and villages, until it is now in shape very much like the letter “S,” long and narrow, while a portion of it, the fifteenth ward, or Algiers, is situated on

the right bank and cut off entirely from the rest of the city.

In this movement upstream and backward towards the lake, New Orleans has swallowed a

large number of towns and villages — almost as many as London itself. And as many of the

districts thus devoured still retain iu ordinary parlance their old titles, it is very confusing to

strangers. Thus, the western portion of New Orleans is never spoken of as the fifteenth ward,

but always as Algiers, recalling the fact that fifteen years ago, it was a city with a complete

municipal government of its own, mayor, council and policemen. The extreme upper portion

of New Orleans, constituting the Sixteenth and Seventeenth wards, is universally known as

Carrollton, while another portion, that bordering on Lake Pontchartrain, still bears the title of

Milneburg, in honor of the philanthropist Milne.

New Orleans comprises today what originally constituted the cities of New Orleans, Algiers,

Carrollton, Jefferson City and Lafayette, the faubourgs Treme, Delord, St. Johnsburg, Marigny,

DeClouet. Sainte Marie, Annonciation, Washington, Neuve Marigny, las Communes, and the

villages of Greenville, Burtheville, Bouligny, Hurstville, Fribourg, Rickerville, Mechanicsville,

Belleville, Bloomington, Freetown, Metairieville, Milneburg. Feinerburg, Gentilly, Marley,

Foucher and others.

Of these, the only names still used to any extent are Algiers, Carrollton, Jefferson.

Greenville, Gentilly, Milneburg and Freetown.

Algiers is that portion of New Orleans on the right, or west bank of the river, where the

Southern Pacific or Louisiana & Texas R. R. has its depot.

Freetown, is a negro suburb of Algiers, lying directly north of it. and between it and Gretna.

Carrollton embraces what is known as the Seventh district or the Sixteenth and Seventeenth

wards. Upper Line street divides it from the remainder of the city. It extends between parallel

lines to Lake Pontchartrain and includes the lake resort or pleasure ground known as West End.

Jefferson City constitutes what is known as the Sixth district, or Twelfth, Thirteenth and

Fourteenth wards. It comprises all that portion of New Orleans between Toledano and Upper

Line streets.

Greenville is that portion of Jefferson next to Carrollton and bordering the river, and in the

immediate neighborhood of the Upper City Park or Exposition Grounds.

Gentilly is the small settlement mainly of farmers, dairy-men and vegetable dealers in the

Bayou Gentilly, a corruption of Chantilly, the celebrated estate of the Condés in France, just

back of the Third district on the line of the Pontchartrain Railroad.

Milneburg is the village lying at the terminus of the Pontchartrain Railroad on Lake Pontchartrain. The terminus of the New Orleans & Lake Road is similarly known as West End, and

that of the New Orleans & Spanish Fort Railroad as Spanish Fort.

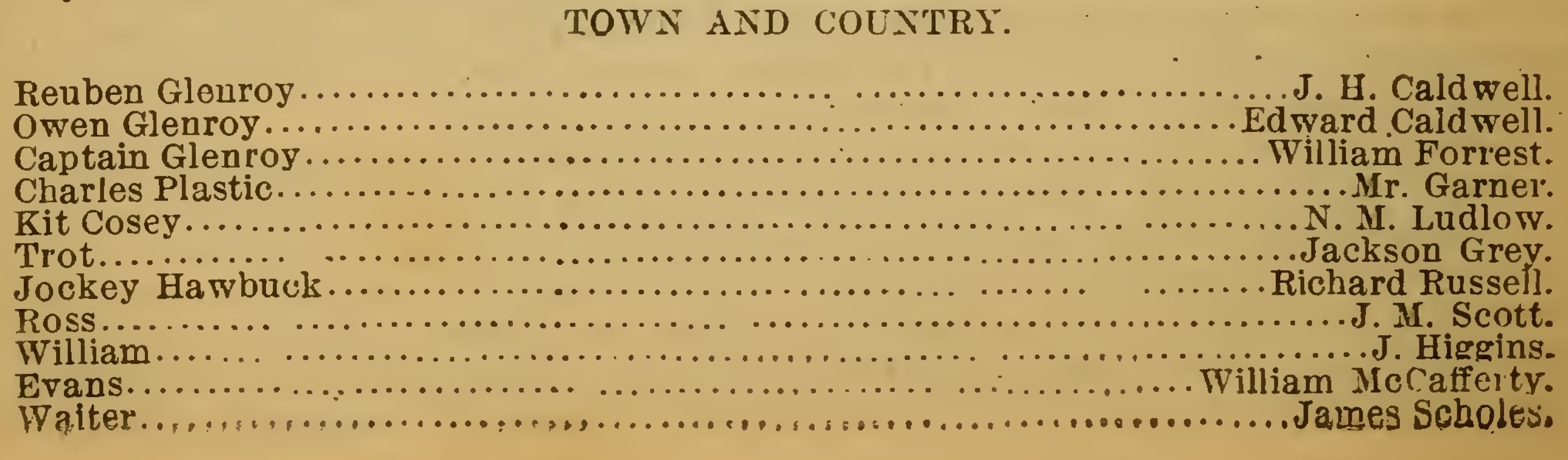

New Orleans includes the entire parish of Orleans, the greater portion of which is an uninhabitable swamp. All the land between the river and lakes Pontchartrain and Borgne is consequently a portion of the city and controlled by municipal laws and ordinances. The total area

subject to municipal government is 187 square miles or 119,680 acres. Of this only a very small

portion, less than one-tenth, is built upon or even cultivated in farms or inhabited. The greater

portion of New Orleans is still covered by the primeval cypress forests and sea swamp and marsh. Chef Menteur, the Rigolets, are part and parcel of the city, although thirty miles distant from a house. Within the municipal limits are the best fishing and duck-hunting resorts in the South, and there are probably sections of the Ninth ward of New Orleans which have never

been visited by man, and as unknown as the centre of Africa. One can easily get lost in these morasses, and several instances of quite recent occurrence are on record of men having been

lost for days and weeks in the cypress swamps, which are a portion of the municipality, and

from which they were rescued when very nearly expiring from starvation.

A short time ago, a writer engaged in preparing sketches of New Orleans scenes, had a photograph taken of the swamp lying in the exact geographical centre of New Orleans, immediately

behind the Boys’ House of Refuge. The photograph was so weird and gloomy that the magazine

declined to print it, confessing that it was a fine sketch, but declaring, at the same time, that no

one would believe for a second, that such a melancholy spot existed in the centre of a great

city.

This condition of affairs is due to the necessity of placing all this country, between the river

and the lakes, under the control of the city authorities, in order to facilitate and improve its

system of drainage. The river being higher than the city and Lake Pontchartrain lower, it has

been found necessary to drain backward through large open canals into the lake.

New Orleans is divided into districts and wards. The wards are the political divisions,

while the districts are mainly used for describing the location of a building. Thus, one seldom

speaks of living in the Third ward, but rather says, “in the first district.”

A still more marked division of the city is that between the French, or Creole, and American

quarters. Canal street, which separates the First and Second districts, is that dividing line, and

separates two towns as widely different in race, language, customs or ideas as two races of

people living close to each other, and separated only by an imaginary line, can well be.

NEW ORLEANS UNDER THE FRENCH AND SPANISH DOMINIONS — VICISSITUDES OF THE

EARLY INHABITANTS — ORIGIN OF THE POPULATION — HOW THE CITY LOOKED IN

1726.

The city of New Orleans was founded in 1718. That is a few men were landed there and put

to work constructing huts and warehouses. In 1719 an overflow occurred which flooded the

entire town, and compelled the men to cease work on the buildings and begin the erection of a

levée around the place in order to prevent a recurrence of the calamity. In 1720, New Orleans was placed under the military command of M. De Noyau. Bienville, in colonial council,

endeavored to have it declared the capital of the colony of Louisiana, instead of old Biloxi, (now

Ocean Springs), but was outvoted.

He sent his chief of engineers, however, Sieur Le Blond de la Tour, a Knight of St. Louis, to

the little settlement, with orders “to choose a suitable site for a city worthy to become the capital of Louisiana.” Stakes were driven, lines drawn, streets marked off, town lots granted,

ditched and palisaded, a rude levée thrown up along the river front, and the scattered settlers of

the neighborhood gathered into the form of a town. To de la Tour, therefore, is due the naming of the streets of the old city.

On Bayou St. John, near this little town, was a settlement of Indians, called Tchoutchouma,

or the place of the Houma or Sun, a title which has been often poetically applied to New

Orleans.

In 1721 warehouses had already been erected, and Bienville (then Governor of Louisiana)

reserved the right to make his residence in the new city on certain governmental regulations.

Finally, in June of the following year, 1722, the royal commissioners having at length given

orders to transfer the seat of government from Biloxi to New Orleans, a gradual removal was

begun of the troops and effects of the Mississippi Company, who had control of Louisiana. In

August, Bienville completed the transfer by moving thither the gubernatorial headquarters.

In the January preceding these accessions the place already contained 100 houses and 300

inhabitants.

It will be seen, therefore, that it was entirely due to Bienville’s perspicuity and obstinacy

that New Orleans was finally made the capital of the French possessions in America. The State

of Louisiana and city of New Orleans have ill requited him. In the U. S. Custom House there is

a basso-rilievo in marble of Bienville, which is the only monument ever erected to him in New

Orleans. A single street bears his name, thanks to de la Tour, his own engineer. Beyond this,

New Orleans has done nothing to honor the man to whom she owes her foundation, and whom

for years her people called “father.”

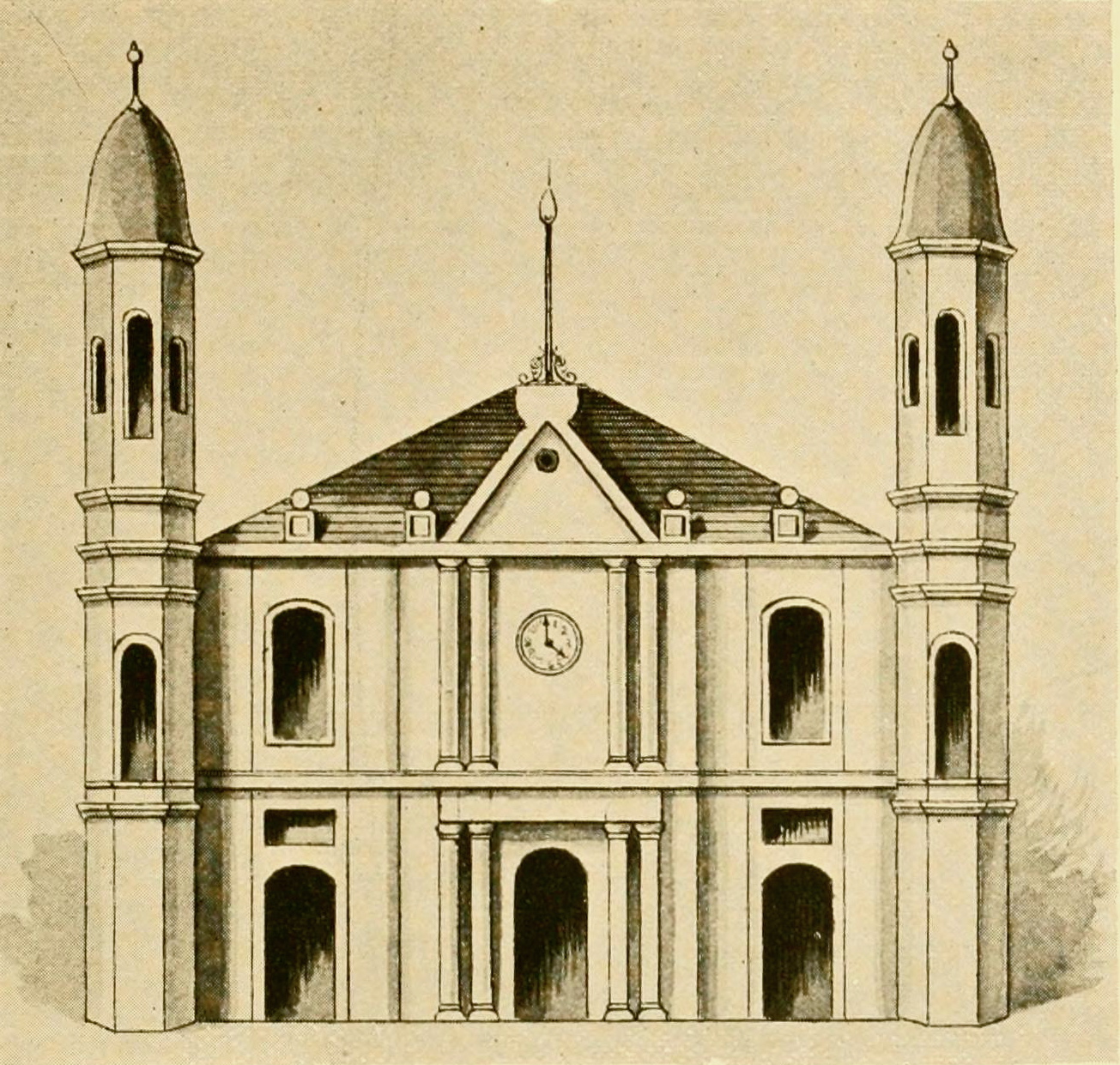

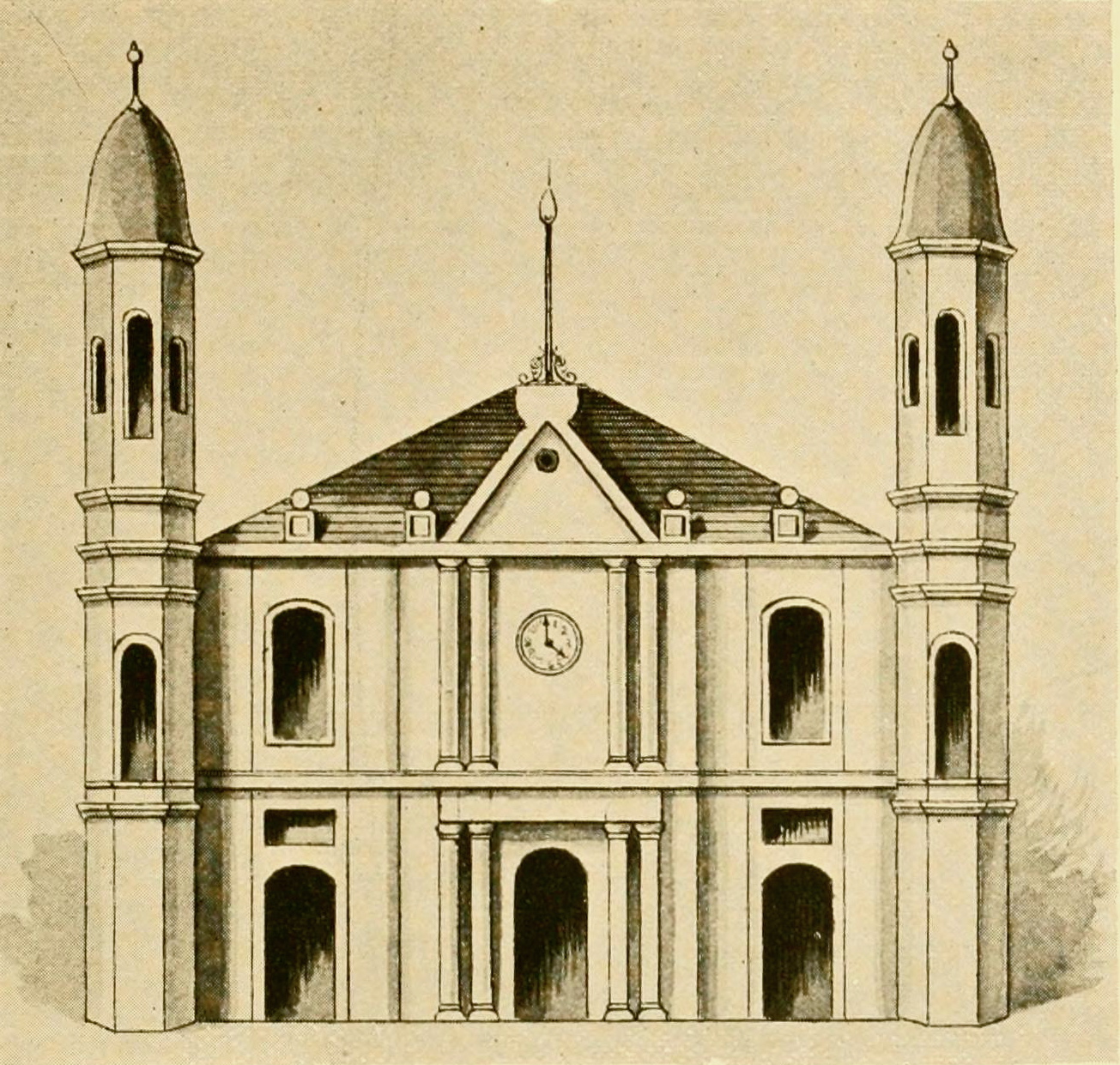

The buildings in the little city must have been very unstable, for the next year, on September 11th, a storm destroyed the parish church — the predecessor of the St. Louis Cathedral, and standing on the same site now occupied by that building — the hospital, and thirty of the one

hundred dwellings the town contained.

The population increased with wonderful rapidity. In 1723, a party of emigrants from

Germany, who had crossed the ocean to settle on lands in Arkansas, granted to them by the

celebrated Law, being disappointed in their original intention, descended the river to New

Orleans, hoping to obtain a passage back to France. This the government was unable to

furnish, but small tracts of land were given to them on both sides of the river about thirty miles

above New Orleans, at what is known as the German Coast, where they settled and engaged in

agricultural pursuits, supplying the city with vegetables and garden products. This was the

commencement of the German element in the population of New Orleans.

Most of these Germans, however, became thoroughly Gallicized in the course of time, and

to-day their descendants speak nothing but French, and most of them bear French titles, having

translated their Teutonic names into French.

In 1732, the population of the little city had grown to 5,000. A few civil and military officials

of high rank had brought their wives with them from France, and a few Canadians had brought

them from Canada, but they were the exceptions. The male portion of the population consisted

principally of soldiers, trappers, miners, galley slaves and redemptioners bound for three years’

service, while the still disproportionally small number of women was almost entirely made up

of transported and unreformed inmates of houses of correction, with a few Choctaw squaws

and African slave women. Gambling, duelling and vicious idleness were indulged in to such an

extent as to give the authorities great concern. The Company addressed its efforts to the improvement of both the architectural and social features of the provincial capital, and the years 1726 and 1727 are conspicuous for these endeavors. The importation of male vagabonds and criminals had already ceased, stringent penalties were laid upon gambling, and steps were taken for promotion of education and religion.

Though the plan of the town comprised a parallelogram of 4,000 feet on the river by a depth of 1,800, and was divided into regular squares of 300 feet, front and depth, yet its appearance was disorderly and squalid. A few board cabins of split cypress (pieux) thatched with cypress bark, were scattered confusedly over the swampy ground, surrounded and isolated from each other by willow brakes, reedy ponds and sloughs bristling with dwarf palmettos and swarming with reptiles.

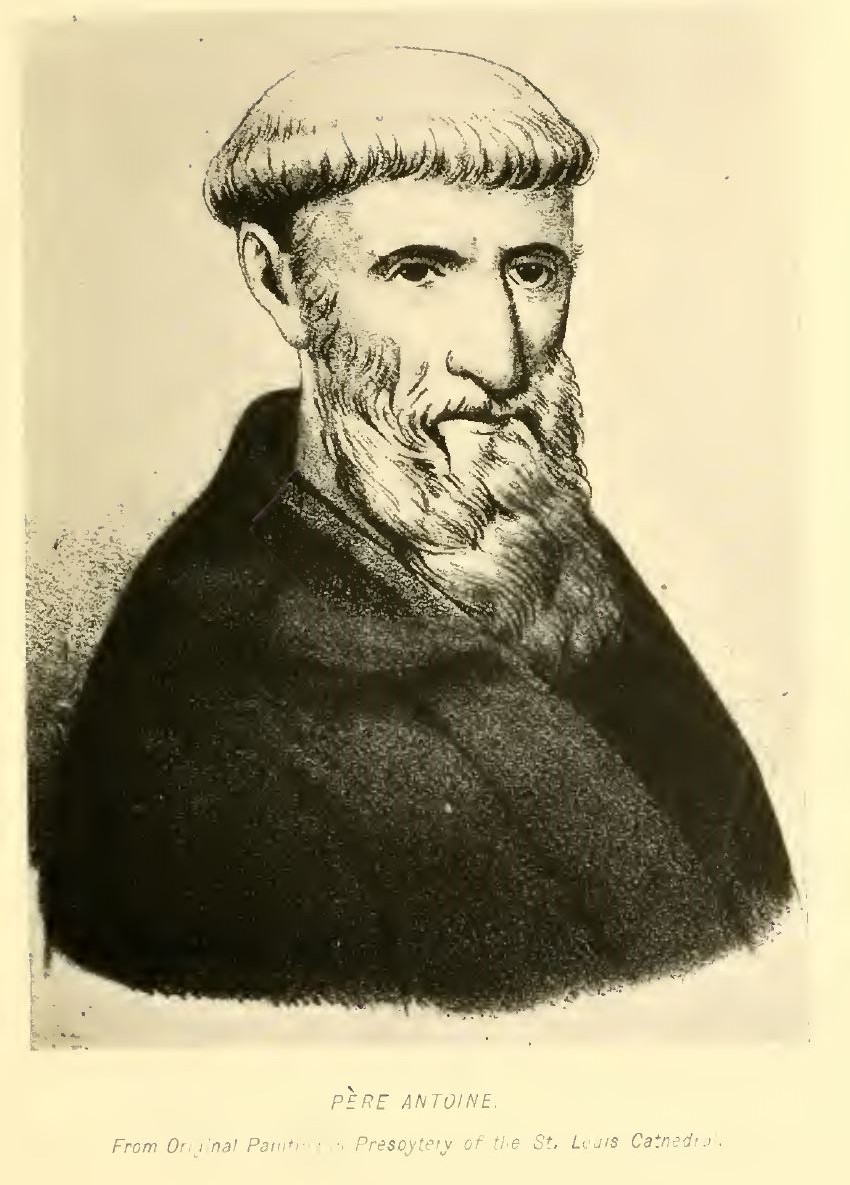

In the middle of the river front two squares had been reserved, the front one as a parade ground or Place d’Armes (now Jackson Square), the other for ecclesiastical purposes. The middle of the rear square had from the first been occupied by a church, and is at present the site of the St.

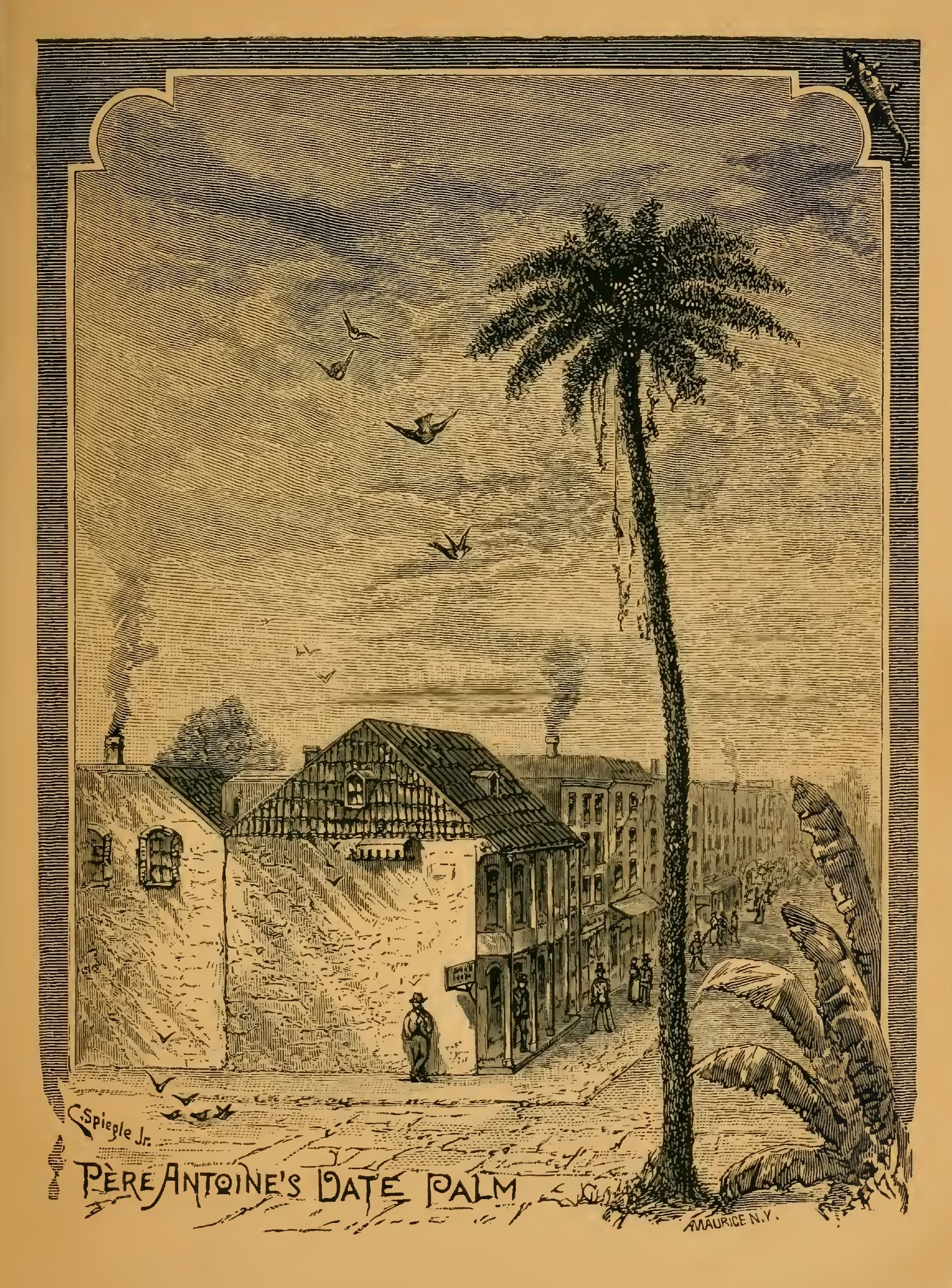

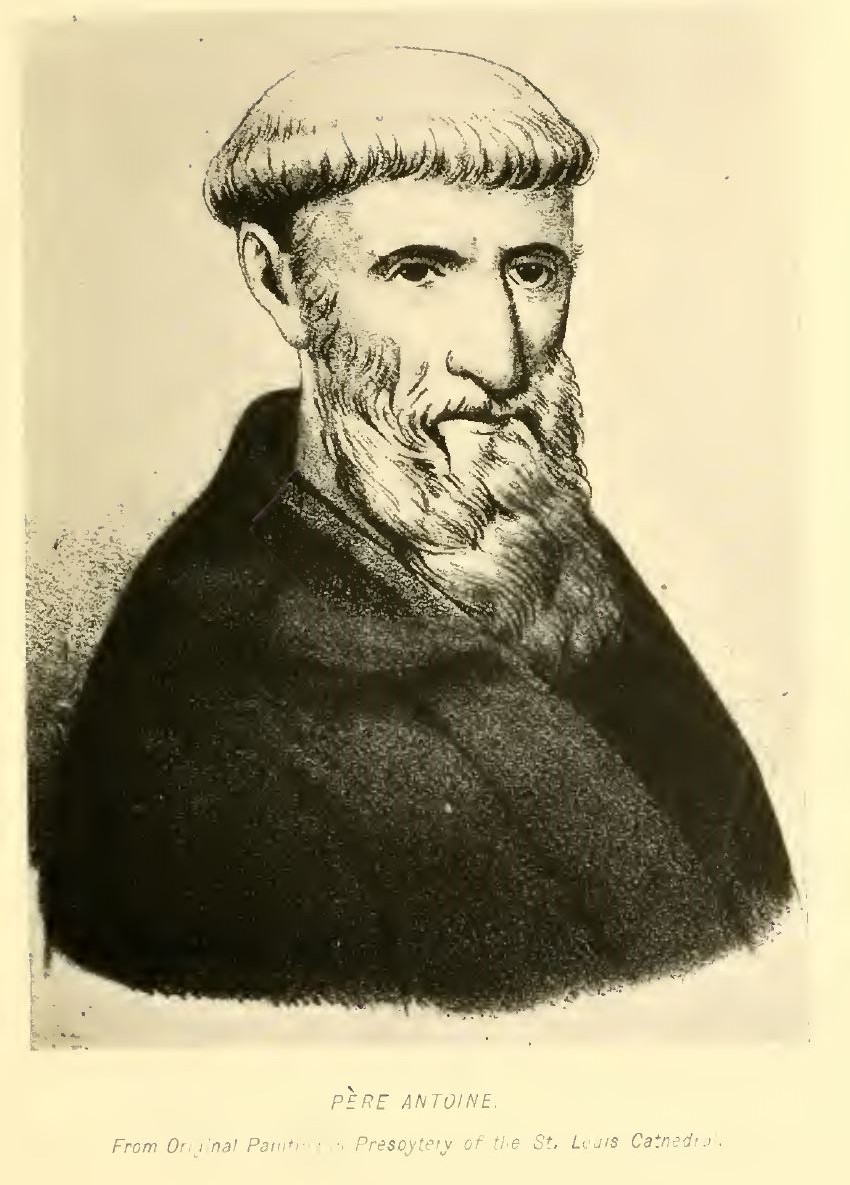

Louis Cathedral. On the left and adjoining the church a company of Capuchin priests erected in 1726 a convent. A company of Ursuline nuns, commissioned to open a school for girls and to

attend to the sick, arrived in 1727 from France, and were given temporary quarters in the house on the north corner of Chartres and Bienville streets, while the foundations of a large and commodious nunnery were laid for them in the square bounded by the river front, Chartres, rue de l’Arsenal (now Ursuline street, in honor of the nuns), and the lower limit of the city, now Hospital street. This building, which was finished in 1730, being then the largest edifice in New Orleans, was occupied by the nuns for ninety-four years, until 1824, when they removed to their present convent below the city. In 1831 the old building became the State House of Louisiana: in 1834 it was made the archiepiscopal palace for the Catholic Archbishop of New Orleans, in which capacity it still serves. It is the oldest building in New Orleans, being in 1885 one hundred

and fifty-five years of age, and as strong and stable as when first built.

A soldiers’ hospital was built near the convent in the square above, which gave to Hospital

street its name.

The Jesuits received the grant of a tract of land immediately above the city, in consideration of which they agreed to educate the youth of New Orleans. This tract was twenty arpents

(3,600 feet) front, by fifty arpents (9,000 feet) depth, and lay within the boundaries now indicated by Common and Terpsichore streets, and back from the River to the Bayou. A further grant of

seven arpents front, adjoining the first grant, made the Jesuits’ plantation cover all the land now

known as the first district. The space between the plantation and the city was declared a terre commune, a pleasure ground not to be built on, but to be used as a public road and for the purposes of fortification. This terre commune marks Common street, which derives its name therefrom.

The Jesuits settled on their plantation in 1727, being furnished with a residence, a chapel,

and slaves to cultivate their lands. They introduced the orange, fig, sugar cane and indigo

plant to Louisiana.

A map of New Orleans, made in 1728 when Perièr was Governor of the colony of Louisiana

shows the ancient Place d’Armes of the same rectangular figure as to-day, an open plot of grass,

crossed by two diagonal paths and occupying the exact middle of the town front. Behind it

stood the parish church of St. Louis, built like most of the public buildings of that day, of

brick. On the right of the church was a small guardhouse and prison, and on the left was the

dwelling of the Capuchins. On the lower side of the Place d’Armes, at the corner of Ste. Anne

and Chartres, were the quarters of the government employees. The grounds facing the Place

d’Armes in St. Peter and Ste. Anne streets were still unoccupied, except by cord-wood and a

few pieces of parked artillery on the one side and a small house for issuing rations on the other.

Just off the river front, on Toulouse street, were the smithies of the Marine, while on the other

hand two long narrow buildings lining either side of the street named in honor of the Due du

Maine, and reaching from the river front nearly to Chartres street, were the King’s warehouses.

Upon the upper corner of the rue de l’Arsenal (now Ursulines) was the hospital, with its

grounds running along the upper side of the street to Chartres, while on the square next below

was the convent of the Ursulines. The barracks and the Company’s forges were in the square,

bounded by Royal, St. Louis, Bourbon and Conti. In the extreme upper portion of the city, on

the river front, at what in later years became the corner of Customhouse and Decatur streets,

were the house and grounds of the Governor; and in the square immediately below them the

humbler quarters transiently occupied by the Jesuits. The Fine residences, built of cypress, or

half brick and half frame, mainly one story and never over two and a half, stood on Chartres

and Royal streets. The poorer people lived in the rear of the city, the greater number of

their houses being located in Orleans street. Prominent among the residents of New Orleans

at that early day, to whom belongs the honor of being the original founders of the city — its

F. F.’s — stand the names Delery, Dalby, St. Martin, Dupuy. Rossard, Duval, Beaulieu-Chauvin,

D’Anseville, Perrigaut, Dreux, Mandeville, Tisseraud, Bonneau, DeBlanc, Dasfeld, Villèré, Provenchè, Gauvrit, Pellerin,

D’Artaguette, Lazon, Raguet, Fleurieu, Brulè, Lafrénièrere, Carrière,

Caron and Pascal. About half these names are now extinct, but the remainder still flourish in

New Orleans and throughout Louisiana.

In that same year, 1728, occurred the one important event, the arrival of a consignment of

reputable girls, sent over by the King of France to the Ursulines, to be disposed of in marriage

by them. They were supplied by the King on their departure from France with a small chest of

clothing, and were long known in the traditions of their colonial descendants by the honorable distinction of the filles de la cassette, or “the casket girls,” to distinguish them from the “correction girls” previously sent over from the prisons and hospitals of Paris.

Incidents of Indian warfare and massacre are not lacking on the pages of the early history

of New Orleans.

It was in 1730 that the Natchez Indians murdered all the French at Fort Rosalie (Natchez)

and at a number of other settlements above New Orleans. All the able-bodied men of the little

city, black as well as white, were armed and sent against them. This was followed in 1732 by a

negro insurrection, which was only suppressed by the execution of the ringleaders, the women

on the gallows, the men on the wheel. The heads of the men were stuck upon posts at the

upper and lower extremities of the town front, and at the Tchoupitoulas settlement, and at

other points, to inspire future would-be conspirators with awe.

In 1758, New Orleans received a considerable accession of population, on account of the

absorption by the British of the French settlements on the upper Ohio, at Fort Duquesne, now

Pittsburgh, and the consequent migration of the French colonists from these points to New

Orleans. This required the construction of additional barracks in the lower part of the city

front, at a point afterwards known by the name of Barracks street (rue des Quartiers). Expecting an attack from the British, Governor Kerlerec seized the opportunity to improve the

fortifications around the town.

The Creoles of New Orleans were at this time greatly agitated over what is known in

Louisiana history as the “Jesuit War,” a quarrel between the Jesuits and Capuchins as to jurisdiction. This strife was characterized by “acrimonious writings, squibs, pasquinades and

satirical songs,” the women in particular taking sides with lively zeal. In July 1763, the

Capuchins were left masters of the field, the Jesuits being expelled from all French and Spanish

possessions on the order of the Pope. Their plantation, which was in a splendid condition and

one of the best in Louisiana, was sold for $180,000, a very large sum in those days.

In November, 1762, the treaty of Fontainebleau was signed, by which France transferred

Louisiana to Spain. The transaction was kept a secret, and it was not until after the lapse of

two years that the people of New Orleans learned with indignation and alarm that they had

been sold to Spain. In March, 1766, the new Spanish Governor, Don Antonio de Ulloa, arrived

with only two companies of Spanish troops. For some time, the incoming Spanish and the outgoing French Governors administered the affairs of the colony, but on October 25th, 1768, a

conspiracy, long and carefully planned, and in which some of the first officers of the government and the leading merchants of New Orleans were engaged, revealed itself in open hostilities.

At the head of this movement were Lafrénièrere, the Attorney-General, Foucault, the intendant

Noyau and Bienville, nephews of the city’s founder, and Milhet, Carresse, Petit, Poupet, Marquis,

DeMasan, Hardy de Bois-Blanc and Villèré, prominent merchants and planters. On the night

of the 28th, the guns at the Tchoupitoulas gate at the upper side of the city were spiked, and the

Acadians, headed by Noyau, and the Germans, by Villèré, entered the city. Ulloa and his

troops retired aboard the Spanish frigate lying in the river and sailed for Havana.

Thus, freed from the Spanish dominion, the project of forming a republic was discussed by the

Louisiana Creoles, and delegates were sent to the British American colonies to propose some

sort of union of all the American colonies. But the republic was short lived.

On August 18th, 1769, Don Alexandro O’Reilly — whom Byron’s Donna Juana mentions so favorably — arrived with 3,600 picked Spanish troops, 50 pieces of artillery, and 24 vessels. TheLouisianians could not resist this force. Twelve of the principal movers of the insurrection were

arrested; six of them shot in the Place d’Armes, and the others imprisoned in the Moro Castle at

Havana.

At the time that O’Reilly took possession of New Orleans, the trade of the city was mainly

in the hands of the English. He soon broke this up, however, refusing to admit any English

vessels to New Orleans. The commercial privileges of the city were, however, gradually

extended. Trade was allowed with Campeachy and the French and Spanish West Indies, under

certain restrictions. The importation of slaves from these islands had long been forbidden on

account of the insurrectionary spirit which existed among them, but the trade in Guinea negroes

was encouraged. In 1778, Galvez gave New Orleans the right to trade with any port in France,

or of the thirteen British colonies, then engaged in their struggle for independence. In 1776,

Oliver Pollock at the head of a number of merchants from New York, Philadelphia, and Boston,

who had established themselves in New Orleans, began, with the countenance of Galvez, to

supply, by fleets of large canoes, the agents of the American cause with arms and ammunition

delivered at Fort Pitt (Pittsburgh).

On Good Friday, March 21st, 1780, occurred the great conflagration which destroyed nearly

the entire city. It began on Chartres street near St. Louis, in the private chapel of Don

Yincento Jose Nuñez, the military treasurer of the colony. The buildings on the immediate

riverfront escaped, but the central portion of the town, including the entire commercial

quarter, the dwellings of the leading inhabitants, the town ball, the arsenal, the jail, the parish

church and the quarters of the Capuchins were completely destroyed. Nineteen squares and

856 houses were destroyed in this fire.

Six years later, on December 8th, 1794, some children playing in a court on Royal street, too

near an adjoining hay store, set fire to it. A strong north wind was blowing at the time, and in

three hours 212. dwellings and stores in the heart of the town, were destroyed. The cathedral,

lately founded on the site of the church, burned in 1788, escaped; but the pecuniary loss

exceeded that of the previous conflagration, which had been estimated at $2,600,000. Only two

stores were left standing, and a large portion of the population was compelled to camp out in

the Place d’Armes and on the levée.

In consequence of these devastating fires, whose ravages were largely attributable to the

inflammable building material in general use, Baron Carondelet, then governor, offered a premium on roofs covered with tiles, instead of shingles, as heretofore; and thus came into use the

tile roof which to-day forms one of the most picturesque features of the old French quarter. As

the heart of the city filled up again it was with better structures, displaying many Spanish-American features — adobe or brick walls, arcades, inner courts, ponderous doors and windows,

balconies, portes cochères, and white or yellow lime-washed stucco. Two-story dwellings took the

place of one-story buildings, and the general appearance as well as the safety of the city was

improved.

New Orleans now made rapid improvement. Don Andres Almonaster y Eoxas, father of

Baroness Pontalba, erected a handsome row of brick buildings on both sides of the Place

d’Armes, where the Pontalba buildings now stand, making the fashionable retail quarter of the

town. In 1787 he built on Ursuline street a chapel of stucco brick for the nuns. The Charity

hospital founded in 1737 by a sailor named Jean Louis, on Rampart, between St. Louis and Toulouse, then outside of the town limits, was destroyed in 1779 by the hurricane. In 1784, Almonaster began and two years later completed, at a cost of $114,000, on the same site, a brick edifice,

which he called the Charity Hospital of St. Charles, a name the institution still bears. In 1792 he

began the erection upon the site of the parish church, destroyed by fire in 1788, of a brick building, and in 1794, when Louisiana and Florida were erected into a bishopric separate from Havana,

this church, sufficiently completed for occupation, became the St. Louis Cathedral. Later

still, he filled the void made by the burning of the town hall and the jail, which, until the conflagration, had stood on the south side of the church, facing the Place d’Armes, with the hall of

the Cabildo, the same that stands there at this time, consecrated to the courts, with the exception of the upper story added since, the French roof which at present distorts its architecture.

The Government itself completed very substantially the barracks begun by Governor Kerlerec, on Barracks street. Close by, it built a military hospital and chapel, and near the upper

river corner of the town, on the square now occupied for the same purpose, but which was then

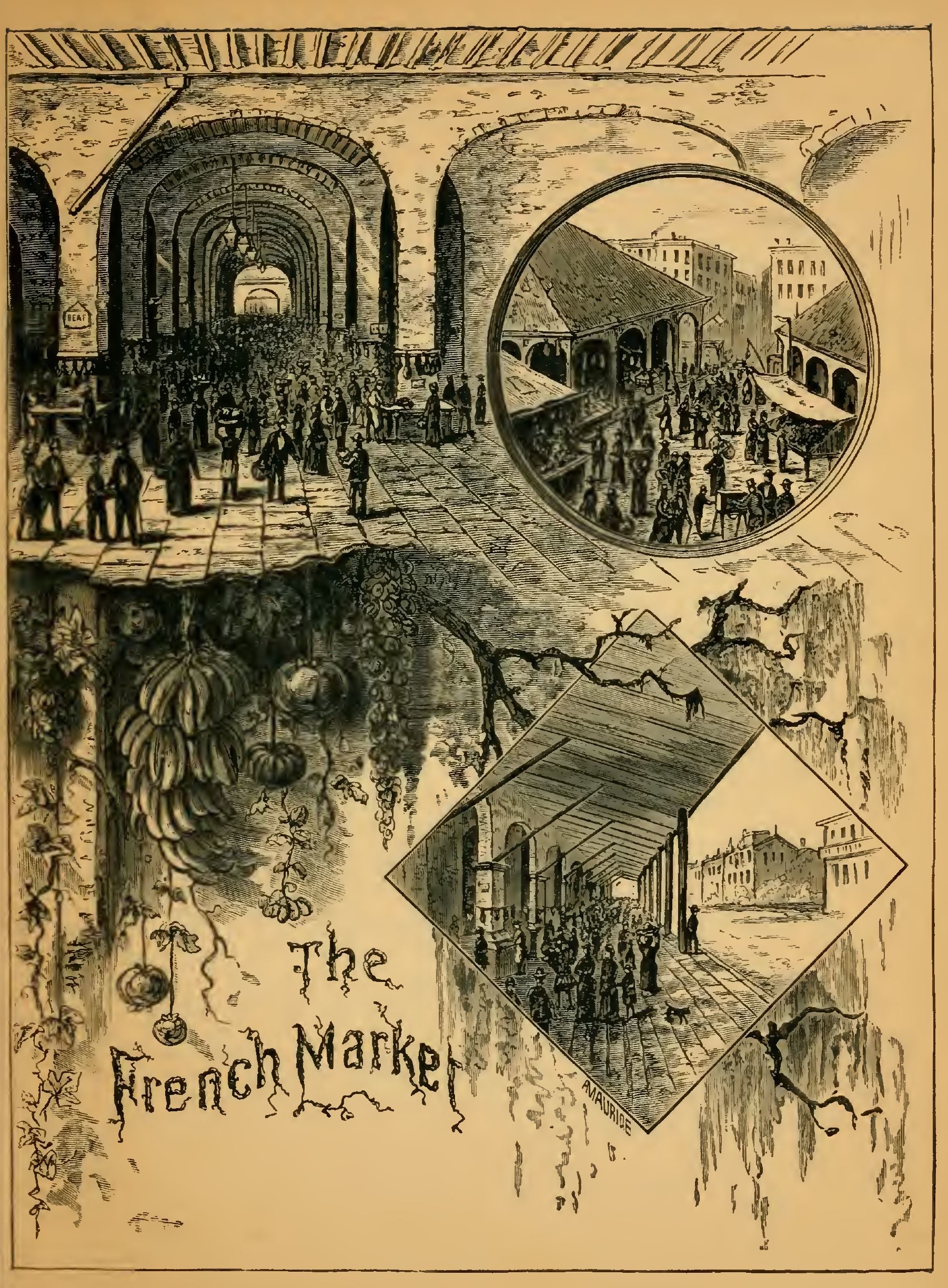

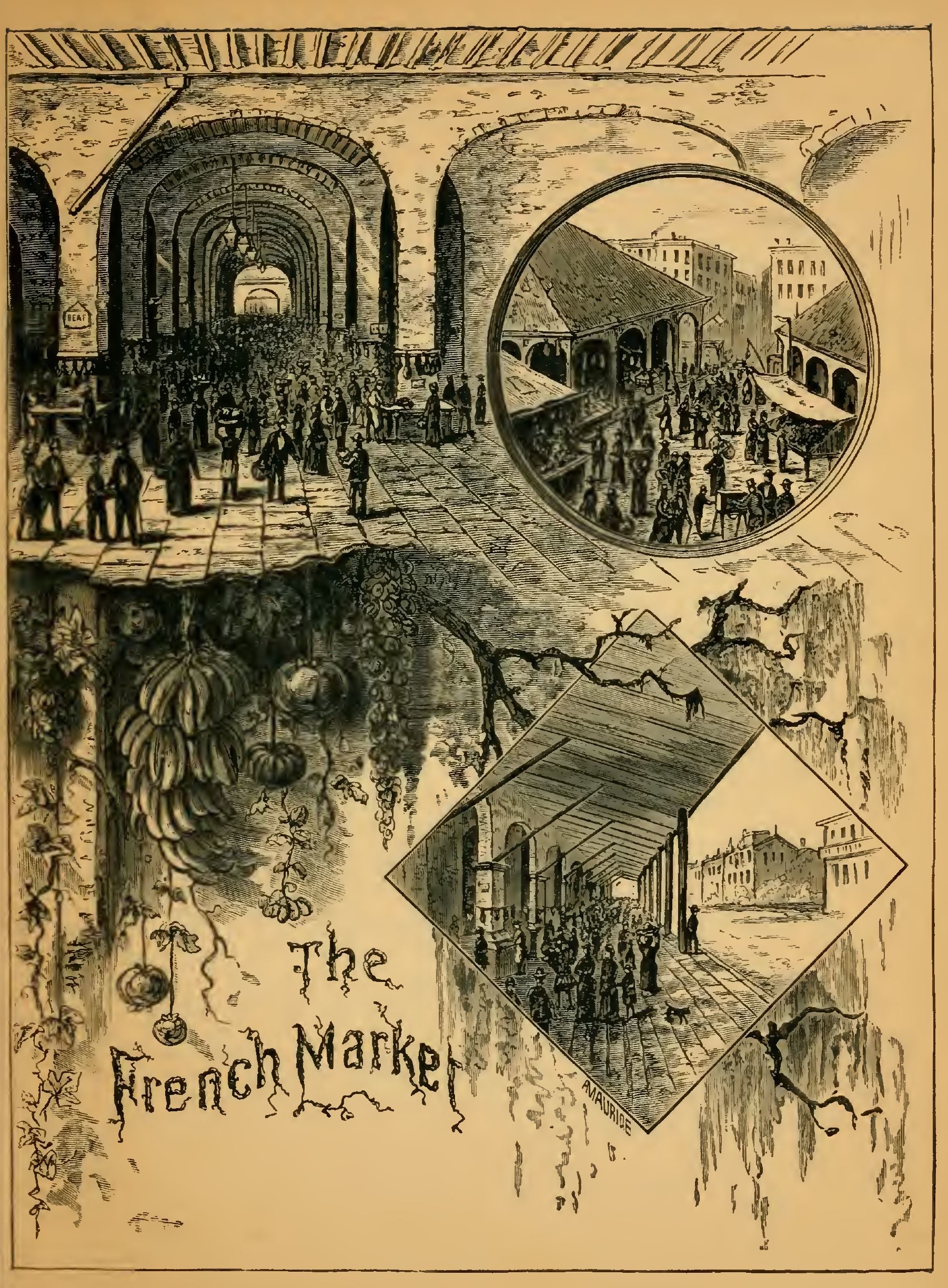

directly on the river, it put up a wooden customhouse. The “Old French market” on the river

front, just below the Place d’Armes, was erected and known as the Halle de Boucherles.

In 1794 Governor Carondelet began, and in the following two years finished, with the aid of

a large force of slaves, the excavation of the “old basin,” and the Carondelet Canal, connecting

New Orleans with Bayou St. John and Lake Pontchartrain.

In 1791 the Creoles of New Orleans became infected with republicanism, and Carondelet

found it necessary to take the same precautions with New Orleans as if he had held a town of

the enemy. The Marseillaise was wildly called for at the theater which some French refugees

from San Domingo had opened, and in the drinking shops was sung

“Ça ira, ça ira, les aristocrates

à la lanterne.”

To ensure safety the fortifications of the city were rebuilt, being completed in 1794. They

consisted of a fort, St. Charles, at the lower river front, with barracks for 150 men, and a parapet 18 feet thick faced with brick, a ditch and a covered way; Fort St. Louis, at the upper river

corner, was similar to this in all regards. The armament of these was twelve 12 and 18-pounders.

At the corner of Canal and Rampart street was Fort Burgundy; on the present Congo

square, Fort St. Joseph, and at what is now the corner of Rampart and Esplanade street, Fort

St. Ferdinand. The wall which passed from fort to fort was 15 feet high, with a fosse in front,

7 feet deep and 40 feet wide, kept filled with water from the Carondelet Canal.

In 1794 étienne de Borè whose plantation occupied the site where the Seventh district of New Orleans (Carrollton) now stands, succeeded in producing $12,000 worth of superior

sugar, and introduced sugar culture into Louisiana.

In 1787, New Orleans was doing a very large export trade for the American possessions, on

the upper Mississippi and Ohio, the goods being shipped to the city on flat boats. In August,

1788, Gen. Wilkinson, received through his agent in New Orleans, viâ the Mississippi, a cargo

of dry goods and other articles, for the Kentucky market, probably the first boatload of

manufactured commodities that ever went up the river to the Ohio.

In 1793, the citizens of the colony were granted the valuable concession of an open commerce with Europe

and America, and a number of merchants from Philadelphia established commercial houses in New Orleans.

On October 20th, 1795, was signed at Madrid, the treaty,which declared the Mississippi free to the people of

the United States, and New Orleans a port of deposit for three years free of any charge.

On the 1st of October, 1800, Louisiana was transferred by Spain to France. It was not

however, until March 26th, 1803, that the French colonial prefect Laussat, landed at New

Orleans, commissioned to prepare for the expected arrival of General Victor, with a large force

of French troops. Instead of General Victor, however, a vessel from France brought the news

in July that Louisiana had been purchased by the United States. On November 3rd, with troops

drawn up in line on the Place d’Armes, and with discharges of artillery, Salcedo, the Spanish

governor, in the hall of the Cabildo, delivered the keys of New Orleans to Laussat. On the 20th

of the next month, Laussat, with similar ceremonies, turned Louisiana over to Commissioners

Claiborne and Wilkinson, and New Orleans became a part of the United States. At that time,

with its suburbs, it possessed a population of 10,000, the great majority of the white population

being Creoles.

NEW ORLEANS UNDER THE SPANISH DOMINION — CONDITION OF THE CITY JUST PREVIOUS

TO ITS ANNEXATION TO THE UNITED STATES — OLD HABITS AND CUSTOMS THAT

STILL SURVIVE.

The traveler approaching New Orleans by the river in the year 1802, would have discerned

at the first glance, what would have seemed a tolerably compactly built town, facing the

levée for a distance of some 1,200 yards from its upper to its lower extremity. From the rue

de la levée (now Decatur street) the town extended in depth (on paper) about 600 yards,

although Dauphiné street was in reality the limit of the inhabited quarter in that direction.

The line of what is now Rampart street was occupied by the palisaded fortification, with a few

forts, all in a greater or less condition of dilapidation. At the upper end of the ramparts was

Fort St. Louis, and on the ground now known as Congo square, was Fort St. Ferdinand, the

chief place for bull and bear fights. Esplanade street was a fortification, beginning at Fort St.

Ferdinand and ending at its junction with the ramparts on Rampart street. Along what is now

Canal street was a moat filled with water, which terminated at a military gate on the Chemin

des Tchoupitoulas, near the levée. Thus was the city protected from siege and attack.

Along the river the city’s upper limit of houses was at about St. Louis street, and the lower

at about St. Philip. The Spanish barracks on Canal street covered the whole block between

what are now known as Hospital and Barracks streets.

The house occupied by the Spanish Governor-General of the province was situated at the

corner of Toulouse and the rue de la levée. It was a plain residence of one story, with the

aspect of an inn. It fronted the river. One side was bordered by a narrow and unpretending

garden in the form of parterre and on the other side ran a low gallery screened by latticework, while the back yard, inclosed by fences, contained the kitchens and the stables. This

house was burned down in 1827, after having been used for the sessions of the Legislature.

Other public buildings, now passed away, were the Military or Royal Hospital, the Public or

Charity Hospital, and a convent of Ursuline nuns. There was no merchants’ exchange for the

transaction of business, no colonial post-office, no college, no library, public or private, and but

one newspaper, the Moniteur de la Louisiane, which, issued once a week, had but a limited

circulation, and was confined to the printing of a few Government orders or proclamations on

local affairs, business advertisements, formulas for passports, bills of lading, and a driblet of

political news, Joachim Salazar, a portrait painter from Mexico, lived in the city at that

period, and testimony to his presence still survives in the shape of portraits to be seen in the

houses of some old families.

In the faubourg that extended above the city, with a frontage of 600 yards by a depth of 300,

were two establishments where cotton was cleaned, put up in bales and weighed. The only

other factory that deserved the name, also in the faubourg, was a sugar refinery, where brown

sugar was transformed into a white sugar of fine appearance. This establishment the city owed

to the enterprise of certain French refugees from San Domingo.

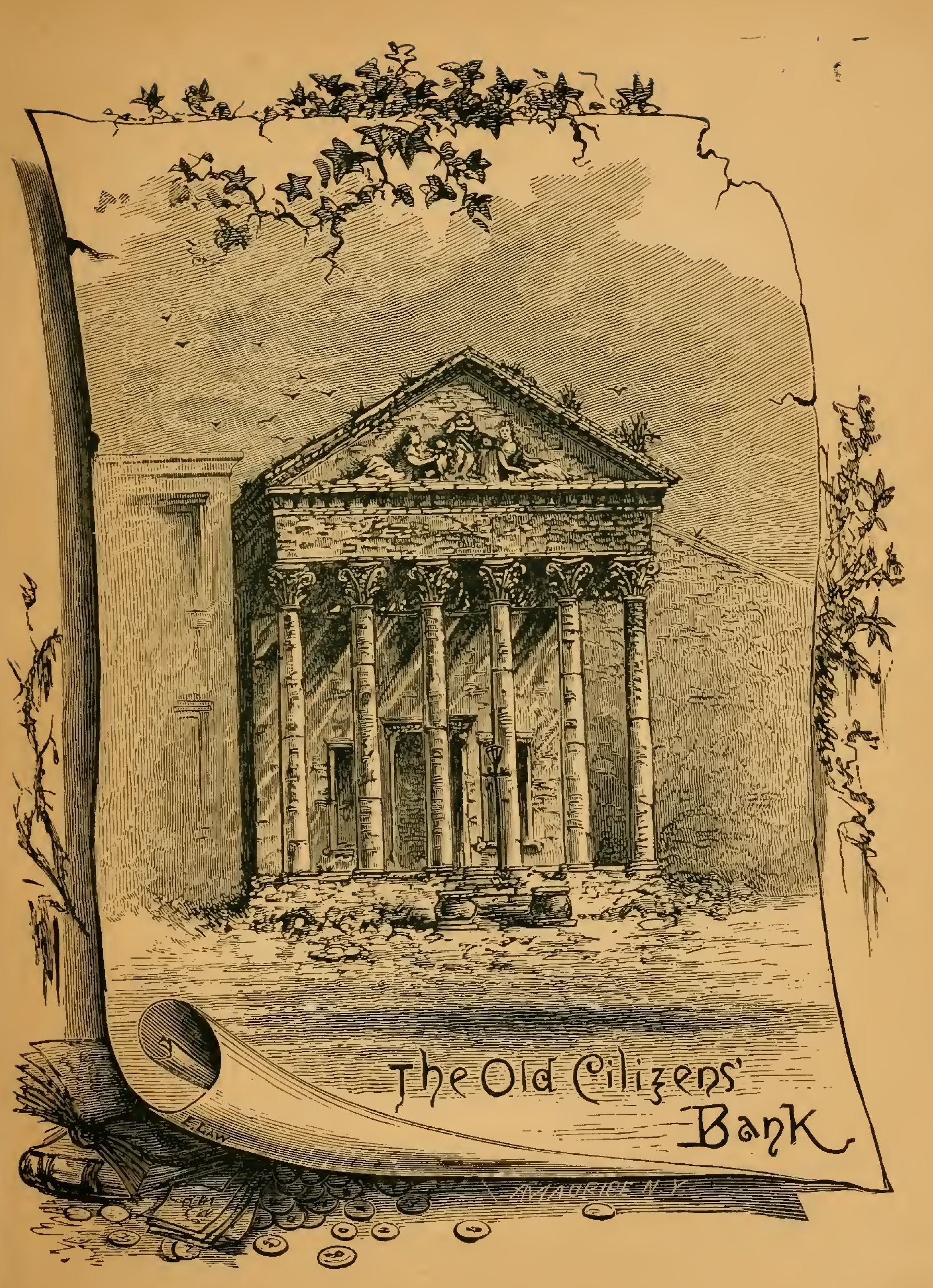

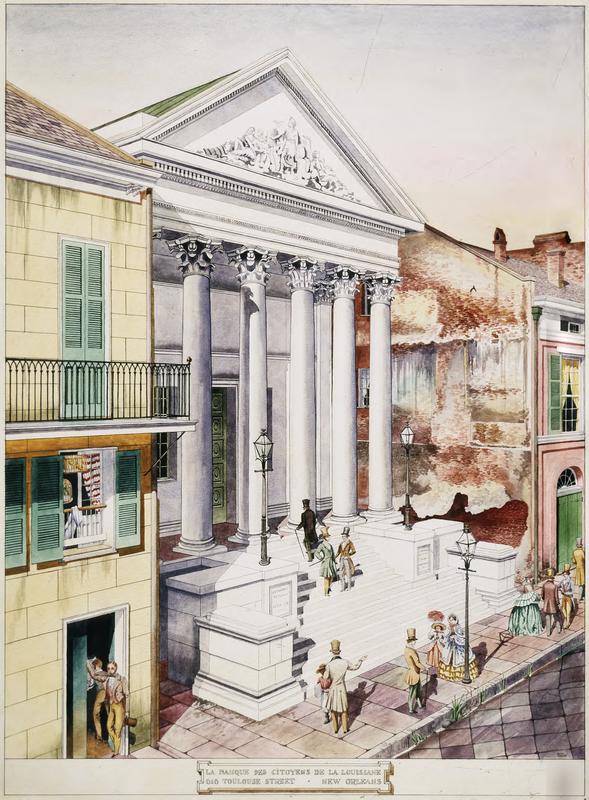

Of the public buildings which are familiar to the eyes of the present generation, only the

French Market, the Cathedral, and the Cabildo, or City Hall, adjoining the Cathedral at the

corner of St. Peter and Chartres streets, still remain. The Cathedral was not yet finished

and lacked those quaint white Spanish towers and the central belfry, which in 1814 and 1815,

were added to it. The “Very Illustrious Cabildo,” which held weekly meetings in this building,

was the municipal body of New Orleans. It was composed of twelve individuals called regidors

awl was presided over by the Governor-General or his Civil Lieutenant. Jackson Square, called

then the Place d’Armes, was used as a review ground for the troops, and was resorted to by nurses

and children, the elders taking their “airing” on the levée or the Grand Chemin that fronted the

houses of the rue de la levée. It was then but a grass plot, barren of trees and used as a playground by the children. It was rather a ghostly place, too, for children to play. A wooden

gallows stood in the middle of it for several years and more than one poor fellow was swung off

into eternity, about the spot where General Jackson now sits in effigy. Then there were no

trees and no flowers, and no watchman to drive away the little fellows at play. The gallows was

not the only stern and forbidding and uncongenial thing about the place either, for the calabosa

stood just opposite; it is the police station now.

Here, in front of the Place d’Armes, everything was congregated — the Cathedral Church of

St. Louis, the convent of the Capuchins, the Government House, the colonial prison or calabosa,

and the government warehouses. Around the square stretched the leading boutiques and

restaurants of the town; on the side, was the market or Halles, where not only meat, fruit and

vegetables were sold, but hats, shoes and handkerchiefs; while in front was the public landing.

Indeed, here was the religious, military, industrial, commercial and social center of the city;

here the troops paraded on fête days, and here even the public executions took place, the

criminals being either shot, or nailed alive in their coffins and then slowly sawed in half. Here,

on holidays, all the varied, heterogeneous population of the town gathered; fiery Louisiana

Creoles, still carrying rapiers, ready for prompt use at the slightest insult to their jealous honor;

habitans, fresh from Canada, rude trappers and hunters, voyageurs and coureurs-de-bois; plain

unpretending ’Cadians from the Attakapas, arrayed in their home-made blue cottonades and

redolent of the herds of cattle they had brought with them; lazy emigré nobles, banished to this

new world under lettres de cachet for interfering with the king’s petits amours or taking too deep

an interest in politics; yellow sirens from San Domingo, speaking a soft bastard French, and

looking so languishingly out of the corners of their big black melting eyes, that it was no wonder

that they led both young and old astray and caused their cold proud sisters of sang pur many a

jealous heart-ache; staid and energetic Germans from “the German coast,” with flaxen hair

and Teutonic names, but speaking the purest of French, come down to the city for supplies;

haughty Castilian soldiers, clad in the bright uniforms of the Spanish cazadores; dirty Indians

of the Houma and Natchez tribes, some free, some slaves; negroes of every shade and hue from

dirty white to deepest black, clad only in braguet and shapeless woolen shirts, as little clothing

as the somewhat loose ideas of the time and country permitted; and lastly, the human trash,

ex-galley slaves and adventurers, shipped to the colony to be gotten rid of. Here, too, in the

Place d’Armes the stranger could shop cheaper if not better than in the boutiques around it, for

half the trade and business of the town was itinerant. Here passed rabbais, or peddling merchants, mainly Catalans and Provençals who, instead of carrying their packs upon their backs,

had their goods spread out in a coffin-shaped vehicle which they wheeled before them; colored

marchandes selling callas and cakes; and milk and coffee women, carrying their immense cans

well balanced upon their turbaned heads. All through the day went up the never-ceasing cries

of the various street hawkers, from the “Barataria! Barataria!” and the “callas tous chauds!”

in the early morning, to the “belles chandelles” that went up, as twilight deepened, from the

sturdy negresses who sold the only light of the colony, horrible, dim, ill-smelling and smoky

candles, made at home from the green wax myrtle.

Lake Pontchartrain was connected with New Orleans by the Carondelet Canal and the

Bayou St. John, by which water-way schooners reached the city from the lake and the neighboring Gulf coast. The canal served moreover to drain the marshy district through which it ran

and to give outlet to the standing waters.

With the exception of levée, Chartres, Royal and perhaps Bourbon streets in the direction of

its breadth, and the streets included between St. Louis and St. Philip in its length, the city was

more in outline than in fact. The other streets comprised within the limits of the town were

regularly laid out, it is true, but they, as well as the faubourg, were but sparsely settled. Along

levée street, Chartres and Royal, and on the intersecting squares included between them, the

houses were of brick, sometimes of two stories, but generally one story high, with small, narrow

balconies. These had been erected witbin a few years, and since the disastrous fires of the years

1788 and 1794, terrible calamities which had compelled the inhabitants to flee for safety to the

Place d’Armes and the levée to avoid death by the flames. Farther back in the town the houses

were of an inferior grade, one story in height, built of cypress and resting on foundations of

piles and bricks, and with shingled roofs. On the outskirts and in the faubourg the houses were

little better than shanties. The sidewalks were four or five feet wide, but walking was sometimes rendered difficult by the projecting steps of the houses.

One of the most disagreeable features of the city in those early days was the condition of

the streets in which not a stone had been laid. A wooden drain served for a gutter, the banquette was also of wood, and the street between the sidewalks was alternately a swamp

and a mass of stifling dust. Wagons dragged along, with the wheels sunk to the hubs

in mud. It was not until 1821 that any systematic attempt was made to pave the streets. The

city, in that year, offered $250 per ton for rock ballast as inducement to ship captains to ballast

with rocks instead of sand, and this plan was quite effectual. In 1822 St. Charles street was

paved for several blocks, and patches of pavement were made on other streets.

Prior to 1815, and, indeed, for some years afterward, the city was lighted by means of oil

lamps suspended from wooden posts, from which an arm projected. The light only penetrated

a very short distance, and it was the custom always to use lanterns on the streets. The order

of march, when a family went out in the evening, was first, a slave bearing a lantern; then

another slave bearing the shoes which were to be worn in the ball-room or theatre, and other articles of full dress that were donned only after the destination was reached, and last, the family.

There were no cisterns in those days, the water of the Mississippi, filtrated, serving as drinking water, while water for common household needs was obtained from wells dug on the premises. Some houses possessed as many as two of these wells.

New Orleans, eighty years ago, was woefully deficient in promenades, drives and places of

public amusement. The favorite promenade was the levée with its King’s road or Chemin des

Tchoupitoulas, where twelve or fifteen Louisiana willow trees were planted, facing the street

corners, and in whose shade were wooden benches without backs, upon which people sat in the

afternoon, sheltered from the setting sun. These trees, which grow rapidly, extended from

about St. Louis street to St. Philip. Outside the city limits was the Bayou road, with all its

inconveniences of mud or dust, leading to the small plantations or truck farms forming the Gentilly district and to those of the Metairie ridge. It was the fashion to spend an hour or two in

the evening on this road, riding on horseback or in carriages of more or less elegance. This

custom was one that had crept in with other luxurious habits within the past eight or ten years,

a period which had been marked by a noticeable growth in the desire for outside show of the

citizens. Almost up to the year 1800 the women of the city, with few exceptions, dressed with

extreme simplicity. But little taste was displayed either in the cut of their garments or in their

ornaments. Head-gear was almost unknown. If a lady went out in summer, it was bareheaded;

if in winter, she usually wore a handkerchief or some such trifle as the Spanish women delight

in. And at home, when the men were not about — so, at least, said those who penetrated there —

she even went about barefooted, shoes being expensive luxuries.

A short round skirt, a long basque-like over garment; the upper part of their attire of one

color and the lower of another, with a profuse display of ribbons and little jewelry — thus

dressed, the mass of the female population of good condition went about visiting, or attended

the ball or theatre. But even three years had made a great change in this respect; and in 1802,

for some reason that it would be difficult to explain, the ladies of the city appeared in attire as

different from that of 1799 as could well be imagined. A surprising richness and elegance of

apparel had taken the place of the primitive and tasteless garb of the few preceding years — a

garb which, had it been seen at the ball or theatre in 1802, would have resembled to the critical

feminine eye a Mardi-Gras disguise. At that peried the natural charms of the ladies were

heightened hy a toilette of most captivating details. Their dresses were of the richest

embroidered muslins, cut in the latest fashions, relieved by soft and brilliant transparent

taffetas, by superb laces, and embroidered with gold. To this must be added rich ear-rings,

collars, bracelets, rings and other adornments. This costume, it is true, was for rare occasions,

and for pleasant weather; but it was a sample of the high art in dress that had come just in the

nick of time to greet the fast-approaching American occupation.

Of the ten thousand people, of all ages, sexes and nationalities, who at that time formed the

permanent population of New Orleans, about four thousand were white — native, European and

American; three thousand free colored, and the rest slave. In addition to these there were

from seven to eight hundred officers and soldiers composing the Spanish garrison, many other

Government underlings, and numerous undomiciliated foreigners. In the ranks of those not

native to the city or the colony were Frenchmen, Spaniards. English, Americans from the

States, Germans, Italians, a few refugees from San Domingo and Martinique, emigrants from the

Canaries and a number of gipsies. The mass of the Frenchmen were small shopkeepers and

cultivators of the soil; the Spaniards were generally in the employment of the Government,

either in the magistracy or the military service, or as clerks; the Catalonians kept shops or

drinking houses; the commercial class comprised chiefly the Americans, the English and the

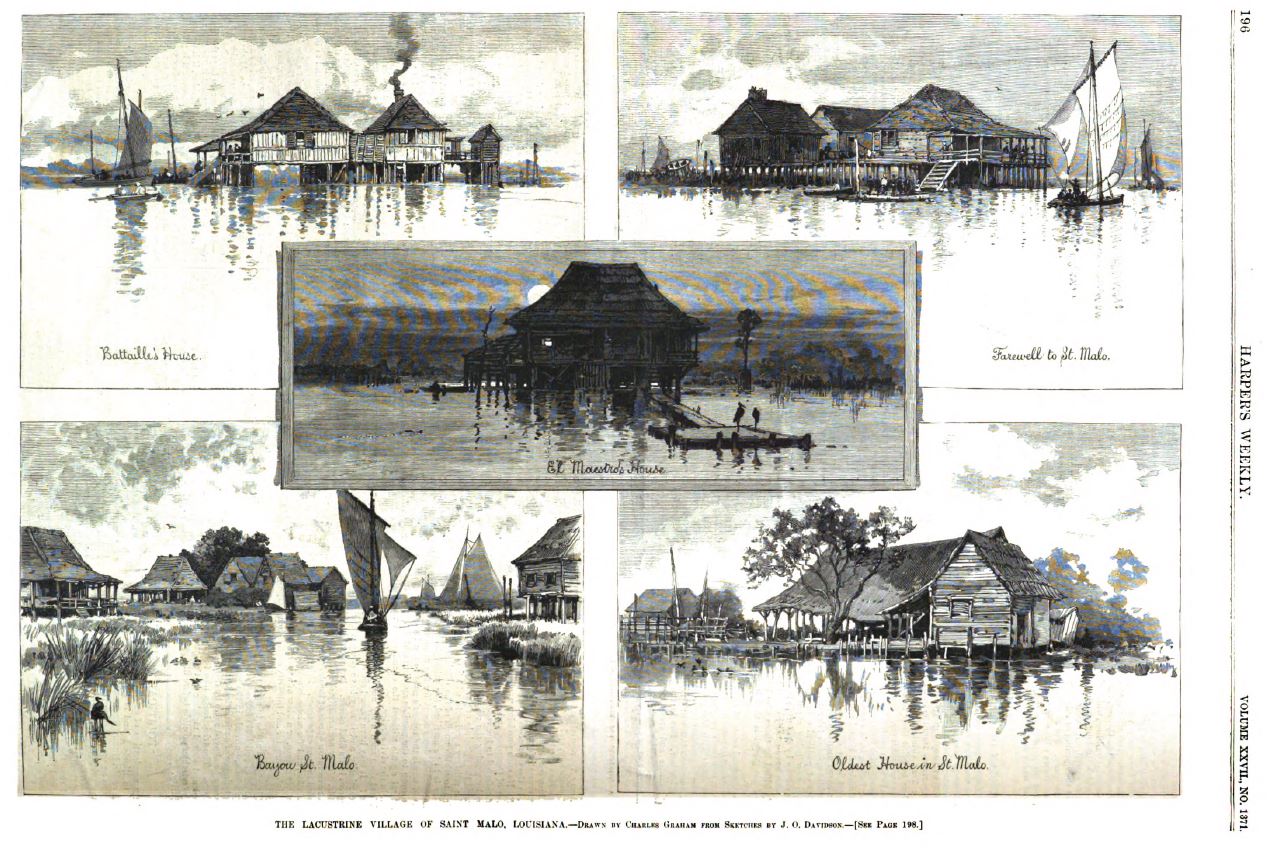

Irish; the Italians were fishermen; the Canary Islanders or Islennes as they were termed,

cultivated vegetable gardens and supplied the market with milk and chickens; and the gipsies

who had been induced to abandon a wandering life, were nearly all musicians or dancers. Of

the Americans, some were of the Kaintock (Kentucky) element, worthy fellows who came

periodically to the city in their flatboats, floating down the river laboriously and bringing with

them up-country produce from the banks of the Ohio and the Illinois, and returning on horseback to their distant homes, by the way of the river-road, after having disposed of their wares.

Kaintock was a generic name given by the Creoles of those days to the Americans who

came from the Upper Mississippi, and, as the name imports, chiefly from the flourishing State of

Kentucky. They were regarded as in some way interlopers on the profound conservatism of the

city. There was an idea of something objectionable — even more so than in the later phrase,

Américain — attached to the word. Creole mothers would sometimes say to ill-behaved and rude

children, “Toi, tu n’es qu’un mauvais Kaintock.” But still, fortunately for the future of New

Orleans, the Kaintock continued to come, clad in his home-spun and home-dyed jeans — sometimes in the hunter’s buckskin garb — the advance guard of that great subsequent immigration

of Américain, who were destined to be seen, ten or fifteen years later, on the streets of the city,

and of whose presence, about 1816, there is still extant In most abominable French, a reminder

in the way of a quatrain which was sung by small boys, white as well as black, natives of the

town, at the passing-by of these strange and unwelcome new-comers —

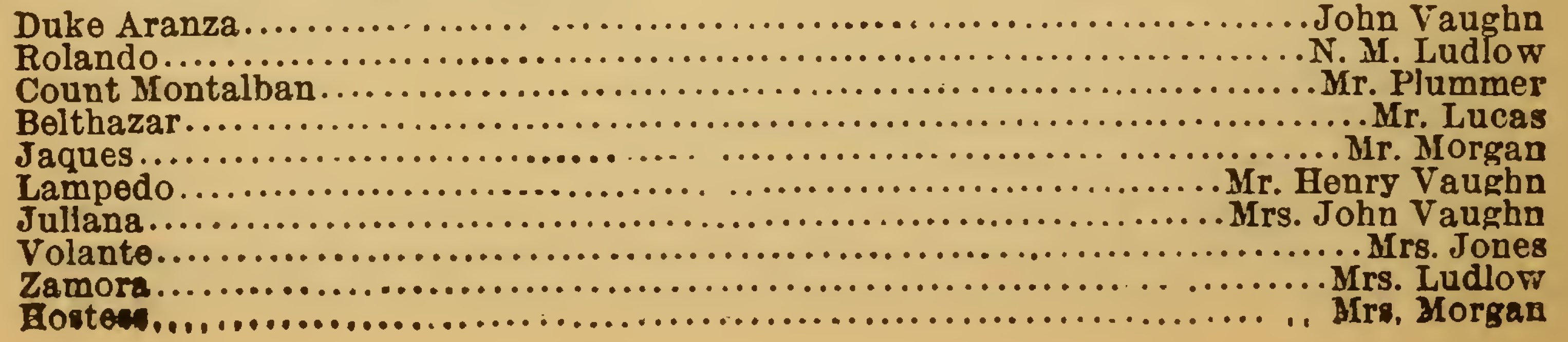

In 1802 New Orleans possessed a theatre — such as it was — situated on St, Peter street, in the

middle of the block between Royal and Bourbon, on the left-hand side going toward the swamp.

It was a long, low wooden structure, built of cypress and alarmingly exposed to the dangers of

fire. Here, in 1799, half a dozen actors and actresses, refugees from the insurrection in San

Domingo, gave acceptable performances, rendering comedy, drama, vaudevilles and comic

operas. But owing to various causes the drama at this place of amusement fell into decline,

the theatre was closed after two years, and the majority of the actors and musicians were

scattered. Some, however, remained, and these, with a few amateurs, residents of the city,

formed another company in 1802. Several pieces were presented, among others one, by the

amateurs, entitled The Death of Cæsar — the character of the illustrious Roman having

been taken by an old citizen who had lived in the colony forty years. This gentleman, who was

an ancient militaire, was very stout, and it required some ingenuity on the part of the audience

to fail to recognize in this personage and in Antony, Brutus, Cassius,

etc., the familiar lineaments of their unheroic camarades in daily life.

The devotees of the dance in those primitive days were compelled by circumstances to

satisfy themselves with accommodations of the plainest description in the exercise of this

amusement in public. In a plain, ill-conditioned, ill-lighted room in a wooden building situated on Condé street, between Ste. Ann and Du Maine — a hall perhaps eighty feet long and thirty

wide — the adepts of Terpsichore met, unmasked, during the months of January and February,

in what was called the Carnival season, to indulge, at the cost of fifty cents per head for

entrance fee, in the fatiguing pleasures of the contre-danses of that day. Some came to dance,

others to look on. Along the sides of the hall were ranged boxes, ascending gradually,

in which usually sat the non-dancing mammas and the wall-flowers of more tender years.

Below these boxes or loges were ranged seats for the benefit of the wearied among the fair

dancers, and between these benches and chairs was a space some three feet in width, which

was usually packed with the male dancers, awaiting their turn, and the lookers-on. The

musicians were composed usually of five or six gipsies; and to the notes of their violins the

dance went on gayly. The hall was usually opened twice a week — one night for adults, and one

night for children — and was under the management of one Jean Louis Ponton, a native of

Brittany, who died in New Orleans about 1820, and who once figured as an English prisoner

of war.

Tradition has preserved the memory of quarrels and affrays that originated in, or were

developed from, this ball-room. Sometimes these quarrels ended in duels with fatal results.

To tread on one’s toes, to brush against one, or to carry off by mistake the lady with whom one

was to dance, was ample grounds for a challenge. Everything was arranged so nicely and

quickly, even in the ball-room itself. The young man who had received the fearful insult of a

crushed corn dropped his lady partner with her chaperone, and had a few minutes’ conversation with some friend of his. In a very short time everything was arranged. A group of five

or six young men would quietly slip out of the ball-room with a careless, indifferent smile on

their faces. A proper place was close at hand. Just back of the Cathedral was a little plot of

ground, known as St. Anthony Square, dedicated to church purposes, but never used. A

heavy growth of shrubbery and evergreens concealed the central portion of this square from

observation; and here, in the very heart of the town and only a few steps from the public ball-room on the rue d’Orléans, a duel could be carried on comfortably and without the least

danger of interruption. If colchemards, or Creole rapiers, which were generally used, and are to

this day, in Creole duels, could be obtained, they were brought into use; but, if this was impossible, the young men had to content themselves with sword-canes. According to the French

code, the first blood, however slight, satisfied jealous honor. The swords were put up again;

the victorious duelist returned to complete his dance, while his victim went home to bandage

himself up.

There was one disturbance in particular, which promised at the time of its occurrence to

provoke a serious riot between the natives and the Spaniards, and which furnishes a significant

commentary on the ill-will that prevailed between the Creoles and their uninvited temporary

rulers. One night the eldest son of the Governor-General, wearied out, perhaps, with the French

contre-danses of the evening, several times interrupted the festivities by calling to the musicians

to play the English contre-danses. At first the citizens, out of respect to him as the son of the Governor, yielded to his arbitrary whim. But finally, seven French contre-danses having been

formed, the Governor’s son again cried out: “Contre-danses Anglaises!” To this, the dancers in

the sets replied, by crying out in a still more animated tone: “Contre-danses Françaises!” The

young Spaniard, backed by some of his adherents repeated his call for the English contre-danses, and as the dancers and the spectators redoubled their cries of “Contre-danses Françaises!”

the young man in the confusion of cries and tongues, ordered the musicians to cease playing,

an order which was promptly obeyed. What followed has been graphically described by a

writer who was in the city shortly after the event.

“The Spanish officer,” says this gentleman, “who was deputed to preserve good order at

this place, thought only of pleasing the Governor’s son, and ordered up his guard composed

of twelve grenadiers, who entered the ball room with swords at their sides and with fixed

bayonets. It is even said that, the tumult having redoubled at the sight of this guard, he

gave the order to fire on the crowd unless it should disperse at once; but that is only what

people say. Imagine, now, the terror of the women, and the fury of the men, whose numbers

were increased by the addition of their friends who flocked in from the gaming-halls. The

grenadiers on one side and the players and dancers on the other were about to come to

blows; on the one hand were guns, bayonets and sabres

— on the other side, swords, benches,

chairs, and whatever could be conveniently utilized as a weapon of offense or defense. During

all this squabble, what was done by several Americans, peaceably disposed individuals, accustomed to the prudent and advantageous role of neutrality, and who had pronounced for neither

the English nor the French contre-danses? They carried away from the battle-field the ladies who

had fainted, and, loaded with these precious burdens, they made a path for themselves through

the bayonets and swords and reached the street.

M——, a French merchant of the city, running from a gaming-room to the assistance of his wife, found her already outside of the dancing

hall in a fainting condition and in the arms of four Americans who were bearing her off.

“The confusion was at its height, and the scene seemed to be about to be transformed

into a bloody one, in which the farce begun by the Governor’s son should end in a tragedy.

It was at this critical moment that three young Frenchmen who had but recently arrived in

the city ascended into the boxes that lined the hall, and harangued the company with eloquence and firmness, urging peace and harmony, in the interest of the sex whose cause they

had espoused. They succeeded, like new Mentors, in calming the agitation of all alike, pacifying the minds of the antagonists, and restoring order and concord. Even the dancing was

resumed and continued the rest of the night in the presence of the old Governor, who repaired

to the spot to affirm by his presence the happy pacification that had been effected; the victory

remained to the French contre-danses, and the officer of the guard escaped with the simple

penalty of being put under arrest next day.”

Bernard Marigny, of the most illustrious family in Louisiana, was a great wag. Among his

friends was a Monsieur Tissier, afterward a prominent judge, who was a confirmed beau, or

dude we would call him in this generation. Marigny delighted in nothing more than to quiz his friend, and did so upon every occasion. Meeting him in the street or in the ball room, Marigny

would throw up his hands, assume an attitude and expression of the most intense admiration,

and exclaim, “What a beau you are! How I do admire you!” Monsieur Tissier bore it for a

longtime without remonstrance, but forbearance at last ceased to be a virtue, and he insisted

that Monsieur Marigny should be more considerate of his feelings. Monsieur Marigny waited

until he met his friend in a ball-room among the ladies, and repeated the offensive exclamation,

whereupon Monsieur Tissier challenged him. The challenge was accepted, pistols were chosen, and

the whilom friends repaired to the Oaks. They were placed in position, and the word was about

to be given, when Monsieur Marigny threw up his hands, his face assumed the old expression

and he said in tones of the deepest grief, “How I admire you! Is it possible that I am soon to

make a corpse of Beau Tissier?” Monsieur Tissier’s anger was not proof against this attack,

and he burst into laughter, threw himself into his opponent’s arms, and the duel was brought to

a sudden and peaceful termination.

Another affair is recorded somewhat later, in which Monsieur Marigny was also one of the

principals. Marigny was sent to the Legislature in 1817, at which time there was a very strong

political antagonism between the Creoles and Americans, which provoked many warm debates

in the House of Representatives and in the Senate. Catahoula parish was represented by a

Georgian giant, an ex-blacksmith, named Humble, a man of plain ways, but possessed of many

sterling qualities. He was remarkable as much for his immense stature as for his political

diplomacy, standing, as he did, nearly seven feet in his stockings. It happened that an

impassioned speech of Monsieur Marigny was replied to by the Georgian, and the latter was so

extremely pointed in his allusions that his opponent felt himself aggrieved and sent a challenge

to mortal combat. The Georgian was non-plussed. “I know nothing of this duelling business,”

said he; “I will not fight him.”

“I am not a gentleman,” replied the honest son of Georgia; “I am only a blacksmith.”

“But you will be ruined if you do not fight,” urged his friends; “you have the choice of

weapons, and you can choose in such a way as to give yourself an equal chance with your

adversary.”

The giant asked time to consider the proposition, and ended by accepting. He sent the following

reply to Monsieur Marigny:

“I accept, and in the exercise of my privilege I stipulate that the duel shall take place in

Lake Pontchartrain in six feet of water, sledge hammers to be used as weapons.”

Monsieur Marigny was about five feet eight inches in height, and his adversary was almost

seven as has been stated. The conceit of the Georgian so pleased Monsieur Marigny, who could

appreciate a joke as well as perpetrate one, that he declared himself satisfied, and the duel did

not take place.

The father of Bernard Marigny, the hero of these anecdotes, was a Creole of immense

wealth and distinction. It was he who received Louis Philippe, when he came to this country,

on his plantation, which comprised the territory afterward laid out as a faubourg, and now the

most densely populated portion of the city. When the father died, Bernard inherited his wealth,

and laid out the plantation in squares, and called it the Faubourg Marigny. The ground was

sold at a large profit and Bernard became the wealthiest man of his time.

However insignificant and rude may seem to us this ball-room of Condé street and of the

year 1802, it must not be supposed that the citizens of that day were not vain of it. Far removed

as they were from the great world and its powerful centres, the good people of our little

municipality looked upon it almost as a Ridotto, a Vauxhall, or a grand bal de l’opéra de Paris.

A singular custom of the period and one so generally observed among the families of

planters living within thirty or forty miles of New Orleans as almost to have been a fashion of

the day, was to transport the sick from the country to the city, there to be treated by the

physicians of the town. Nearly every well-regulated family possessed its copy of the medical hand-books

of Tissot and Duchan (translated) and when, on the occasion of sickness, it became

necessary to prescribe medicines, these were the authorities consulted. But when the sickness

threatened to become serious the patient was brought to New Orleans and placed in the hands

of one of the dozen or so surgeons who practiced in the city and who were, indifferently,

surgeons, physicians, apothecaries, and even accoucheurs, according to the necessities of the

case.

The authority of the Spanish rulers of the colony was mildly exercised in 1802. The citizens

of New Orleans, assured full liberty under the civil and municipal rather than military rule that

prevailed, had little reason to complain. Everyone, in town and country, enjoyed the ordinary

independence of the law-abiding citizen. The duty of preserving the peace was confided to a

few soldiers and citizens who patrolled the streets, rather negligently it must be confessed.

Hence crimes were not infrequent — a result which might have been anticipated from the number

of cabarets, constantly open, where the white and black canaille, thieves, etc., drank to excess,

night and day, and from the numerous gambling dens and ball-rooms of the lower class. One of

these last, the maison Coquet, notorious in its day, situated nearly in the center of the town,

often posted its advertisements at the street corners, with the express permission, as announced

in the placard, of the Honorable Civil Governor of the city.

Rents on the rue de la levée and the streets nearest to the river were much higher than in

other parts of the town. Immigration had tended to double the price of nearly every com-

modity, and as the commerce of the place was carried on near the levée, in front of the city,

where were moored the flatboats, the pirogues (small vessels of six or eight tons, with a latteen

sail), and the schooners and few barks and ships that constituted the shipping, rooms and

houses in that quarter were held at high rents. A barrel of rice cost in the market from eight to

nine dollars; a turkey from $1.50 to $2.00; a capon from 75 cents to $1.00; a hen from 50 cents to

75 cents; a pair of small pigeons 75 cents; a barrel of flour from seven to eight dollars. The

average expenses, without superfluities, of a family consisting of father, mother, a few children

and two or three servants, would have amounted to not less than $2,000 per annum under

ordinary circumstances.

The city was guarded at night by Spanish watchmen, who sang out the hours as well as the

state of the weather — “nine o’clock and cloudy,” or “ten o’clock and the weather is clear,” as the

case might be. In the daytime the gens d’armes patrolled the city in squads of four or five, each

with a full uniform of gold lace, cocked hat and sword. Many were the battles fought between

the gens d’armes and the flatboatmen.

The city guard of those days wore a most imposing uniform. His cocked hat, his deep-blue

frock coat, his breast straps of black leather supporting cartridge box and bayonet scabbard, his

old flint-lock musket and his short sword made him an object of profound respect on the part of

the small boys, and a terror to the slaves who happened to be out a little late. These proud old

guardians of the peace were not compelled to do beat duty. Early in the evening the sergeant

would gather his squad together in the guardroom, which adjoined the old calaboose, and under

his orders the corporal would put his men through the manual of arms. Then with muskets at

a right shoulder, they would march off on their patrol.

The limits extended as far up as Canal, down to Esplanade street and back to Rampart.

Beyond this, nothing but swamps and neighboring plantations were to be seen. After making a

tour they returned to the guardroom, to make a second round later. If a disturbance occurred

the guard had to be sent for, as it would have been almost a breach of discipline to have been

on hand in time to prevent a fight, or to disperse a crowd before a riot had already taken

place.

They bore themselves with that stern, sullen demeanor that awed the peaceable and amused

the gay spirits of those days. Frequently in the upper portion of the city, where the Kentucky

flatboatmen mostly did congregate, were the gens d’armes ignominiously put to flight, swords,

muskets and all.

The old calaboose in which they incarcerated the victims of their displeasure was a curious

old building of Spanish style. It was situated on St. Peter street, just in the rear of

what is now the Supreme Court room, and occupied all the space down to within about

fifty feet of Royal street, where now there are private dwellings. It was two stories in

height, with walls of great thickness. Opening on St. Peter street where now runs St. Anthony’s alley, near the Arsenal, was the huge iron gateway. The ponderous door was one

mass of bars and crossbars and opened upon an ante-room, on either side of which were

the officers’ rooms. Passing through a second iron door one entered the body of the prison,

a gloomy, dismal-looking place, as silent as the dungeons of the old Inquisition. A number

of windows opened on the street, through which the inmates drew what little fresh air they

got. The building was put up in the year 1795, by Don Almonaster, when the Cabildo or City

Council occupied the present Supreme Court rooms. When the Territorial Government of

Louisiana was formed it was still used as a calaboose, and, as imprisonment for debt was

then allowed, its upper story was given up to unfortunate debtors.

After the close of the war with England, New Orleans began to grow rapidly, and overflowed beyond

its ancient boundaries. The old Marigny plantation below had been cut up

into squares, and new comers were building there, whilst, above, scattered houses showed

that the people could not be confined to the narrow and restricted limits of the ramparts.

A new and larger prison became necessary, and in 1834 the foundations for the present

Parish Prison were laid just back of Congo square. As soon as it was completed all the

prisoners were carried thither, and the work of demolishing the calaboose was commenced.

It was a work of much more difficulty than was expected. The mortar of the Spaniards,

made from the lime of lake shells, was as tenacious as the most durable cement, and would

not yield. It was found easier to cut through the solid bricks than to try to separate them,

and, therefore, the work of tearing the old donjon down occupied some time. There is a

story of how the workmen discovered skeletons bricked up in the walls, and chains and

shackles in the vaults, but none of our citizens who were living at that time ever saw any

of those ghastly souvenirs of Spanish rule.

Beneath the building, it is true, they came across some three or four deep vaults, which

had not apparently been used for years, and this was enough to give rise to the report

that they had discovered the dungeons of the Spanish Inquisition. The tale has come down, and

many old Creoles still believe it.

After it had been razed to the ground, parties claimed the ground, alleging that the Spanish

Government had occupied the site without reimbursing them, and accordingly it was awarded

to them, and private dwellings were built upon it, saving an alleyway, which now intersects

Cathedral Alley.

In those days flatboating was a business of immense proportions. The flatboatman was a

distinct character, like no one else in the world, and disposed to believed himself a superior

being. Rough as he was, a great deal was owed to him, and his lack of refinement is lost sight

of in the contemplation of his worth as a pioneer. He was the only medium of trade in those

days with the Northwest, and his real importance was, perhaps, not overrated even by himself.

The crews of the flatboats, after a passage of many weeks, during which they underwent

hardships that we know nothing of in these days of railroads and steamboats, were disposed to

enjoy themselves at the end of their journey, and their idea of enjoyment was in harmony with

their rough lives. When they came on shore they spent their money like lords, and assumed

privileges in accordance with their individual views of their own importance. They resented

interference, and were disposed to protect their rights with their muscle.

The natural consequence was war. In these battles the flatboatmen, armed with clubs,

were as often victorious as the gens d’armes, armed with swords. When their carousals were

over they went peaceably across the lake on some sailing craft, and made their way back to

their Northern homes overland and on foot, throngh the Indian country, leaving their boats to be

utilized as junk shops, or to be still more debased by doing duty as sidewalks or banquettes.