Ida B. Wells-Barnett.

Mob Rule in New Orleans.

IN

NEW ORLEANS

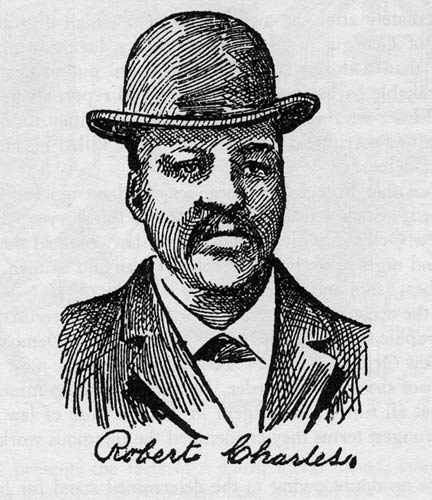

ROBERT CHARLES

AND

His Fight to Death,

the story of his life,

burning human beings alive,

other lynching statistics.

IDA B. WELLS-BARNETT

CHICAGO

1900

INTRODUCTION

Immediately after the awful barbarism which disgraced the State of Georgia in April of last year, during which time more than a dozen colored people were put to death with unspeakable barbarity, I published a full report showing that Sam Hose, who was burned to death during that time, never committed a criminal assault, and that he killed his employer in self-defense.

Since that time I have been engaged on a work not yet finished, which I interrupt now to tell the story of the mob in New Orleans, which, despising all law, roamed the streets day and night, searching for colored men and women, whom they beat, shot and killed at will.

In the account of the New Orleans mob I have used freely the graphic reports of the New Orleans Times-Democrat and the New Orleans Picayune. Both papers gave the most minute details of the week’s disorder. In their editorial comment they were at all times most urgent in their defense of law and in the strongest terms they condemned the infamous work of the mob.

It is no doubt owing to the determined stand for law and order taken by these great dailies and the courageous action taken by the best citizens of New Orleans, who rallied to the support of the civic authorities, that prevented a massacre of colored people awful to contemplate.

For the accounts and illustrations taken from the above-named journals, sincere thanks are hereby expressed.

The publisher hereof does not attempt to moralize over the deplorable condition of affairs shown in this publication, but simply presents the facts in a plain, unvarnished, connected way, so that he who runs may read. We do not believe that the American people who have encouraged such scenes by their indifference will read unmoved these accounts of brutality, injustice and oppression. We do not believe that the moral conscience of the nation — that which is highest and best among us — will always remain silent in face of such outrages, for God is not dead, and His Spirit is not entirely driven from men’s hearts.

When this conscience wakes and speaks out in thunder tones, as it must, it will need facts to use as a weapon against injustice, barbarism and wrong. It is for this reason that I carefully compile, print and send forth these facts. If the reader can do no more, he can pass this pamphlet on to another, or send to the bureau addresses of those to whom he can order copies mailed.

Besides the New Orleans case, a history of burnings in this country is given, together with a table of lynchings for the past eighteen years. Those who would like to assist in the work of disseminating these facts, can do so by ordering copies, which are furnished at greatly reduced rates for gratuitous distribution. The bureau has no funds and is entirely dependent upon contributions from friends and members in carrying on the work.

Ida B. Wells-Barnett

Chicago, Sept. 1, 1900

MOB RULE IN NEW ORLEANS

SHOT AN OFFICER

The bloodiest week which New Orleans has known since the massacre of the Italians in 1892 was ushered in Monday, July 24, by the inexcusable and unprovoked assault upon two colored men by police officers of New Orleans. Fortified by the assurance born of long experience in the New Orleans service, three policemen, Sergeant Aucoin, Officer Mora and Officer Cantrelle, observing two colored men sitting on doorsteps on Dryades street, between Washington Avenue and 6th Streets, determined, without a shadow of authority, to arrest them. One of the colored men was named Robert Charles, the other was a lad of nineteen named Leonard Pierce. The colored men had left their homes, a few blocks distant, about an hour prior, and had been sitting upon the doorsteps for a short time talking together. They had not broken the peace in any way whatever, no warrant was in the policemen’s hands justifying their arrest, and no crime had been committed of which they were the suspects. The policemen, however, secure in the firm belief that they could do anything to a Negro that they wished, approached the two men, and in less than three minutes from the time they accosted them attempted to put both colored men under arrest. The younger of the two men, Pierce, submitted to arrest, for the officer, Cantrelle, who accosted him, put his gun in the young man’s face ready to blow his brains out if he moved. The other colored man, Charles, was made the victim of a savage attack by Officer Mora, who used a billet and then drew a gun and tried to kill Charles. Charles drew his gun nearly as quickly as the policeman, and began a duel in the street, in which both participants were shot. The policeman got the worst of the duel, and fell helpless to the sidewalk. Charles made his escape. Cantrelle took Pierce, his captive, to the police station, to which place Mora, the wounded officer, was also taken, and a man hunt at once instituted for Charles, the wounded fugitive.

In any law-abiding community Charles would have been justified in delivering himself up immediately to the properly constituted authorities and asking a trial by a jury of his peers. He could have been certain that in resisting an unwarranted arrest he had a right to defend his life, even to the point of taking one in that defense, but Charles knew that his arrest in New Orleans, even for defending his life, meant nothing short of a long term in the penitentiary, and still more probable death by lynching at the hands of a cowardly mob. He very bravely determined to protect his life as long as he had breath in his body and strength to draw a hair trigger on his would-be murderers. How well he was justified in that belief is well shown by the newspaper accounts which were given of this transaction. Without a single line of evidence to justify the assertion, the New Orleans daily papers at once declared that both Pierce and Charles were desperadoes, that they were contemplating a burglary and that they began the assault upon the policemen. It is interesting to note how the two leading papers of New Orleans, the Picayune and the Times-Democrat, exert themselves to justify the policemen in the absolutely unprovoked attack upon the two colored men. As these two papers did all in their power to give an excuse for the action of the policemen, it is interesting to note their versions. The Times-Democrat of Tuesday morning, the twenty-fifth, says:

Two blacks, who are desperate men, and no doubt will be proven burglars, made it interesting and dangerous for three bluecoats on Dryades street, between Washington Avenue and Sixth Street, the Negroes using pistols first and dropping Patrolman Mora. But the desperate darkies did not go free, for the taller of the two, Robinson, is badly wounded and under cover, while Leonard Pierce is in jail.

For a long time that particular neighborhood has been troubled with bad Negroes, and the neighbors were complaining to the Sixth Precinct police about them. But of late Pierce and Robinson had been camping on a door step on the street, and the people regarded their actions as suspicious. It got to such a point that some of the residents were afraid to go to bed, and last night this was told Sergeant Aucoin, who was rounding up his men. He had just picked up Officers Mora and Cantrell, on Washington Avenue and Dryades Street, and catching a glimpse of the blacks on the steps, he said he would go over and warn the men to get away from the street. So the patrolmen followed, and Sergeant Aucoin asked the smaller fellow, Pierce, if he lived there. The answer was short and impertinent, the black saying he did not, and with that both Pierce and Robinson drew up to their full height.

For the moment the sergeant did not think that the Negroes meant fight, and he was on the point of ordering them away when Robinson slipped his pistol from his pocket. Pierce had his revolver out, too, and he fired twice, point blank at the sergeant, and just then Robinson began shooting at the patrolmen. In a second or so the policemen and blacks were fighting with their revolvers, the sergeant having a duel with Pierce, while Cantrell and Mora drew their line of fire on Robinson, who was working his revolver for all he was worth. One of his shots took Mora in the right hip, another caught his index finger on the right hand, and a third struck the small finger of the left hand. Poor Mora was done for; he could not fight any more, but Cantrell kept up his fire, being answered by the big black. Pierce’s revolver broke down, the cartridges snapping, and he threw up his hands, begging for quarter.

The sergeant lowered his pistol and some citizens ran over to where the shooting was going on. One of the bullets that went at Robinson caught him in the breast and he began running, turning out Sixth Street, with Cantrell behind him, shooting every few steps. He was loading his revolver again, but did not use it after the start he took, and in a little while Officer Cantrell lost the man in the darkness.

Pierce was made a prisoner and hurried to the Sixth Precinct police station, where he was charged with shooting and wounding. The sergeant sent for an ambulance, and Mora was taken to the hospital, the wound in the hip being serious.

A search was made for Robinson, but he could not be found, and even at 2 o’clock this morning Captain Day, with Sergeant Aucoin and Corporals Perrier and Trenchard, with a good squad of men, were beating the weeds for the black.

The New Orleans Picayune of the same date described the occurrence, and from its account one would think it was an entirely different affair. Both of the two accounts cannot be true, and the unquestioned fact is that neither of them sets out the facts as they occurred. Both accounts attempt to fix the beginning of hostilities upon the colored men, but both were compelled to admit that the colored men were sitting on the doorsteps quietly conversing with one another when the three policemen went up and accosted them. The Times-Democrat unguardedly states that one of the two colored men tried to run away; that Mora seized him and then drew his billy and struck him on the head; that Charles broke away from him and started to run, after which the shooting began. The Picayune, however, declares that Pierce began the firing and that his two shots point blank at Aucoin were the first shots of the fight. As a matter of fact, Pierce never fired a single shot before he was covered by Aucoin’s revolver. Charles and the officers did all the shooting. The Picayune’s account is as follows:

Patrolman Mora was shot in the right hip and dangerously wounded last night at 11:30 o’clock in Dryades Street, between Washington and Sixth, by two Negroes, who were sitting on a door step in the neighborhood.

The shooting of Patrolman Mora brings to memory the fact that he was one of the partners of Patrolman Trimp, who was shot by a Negro soldier of the United States government during the progress of the Spanish-American war. The shooting of Mora by the Negro last night is a very simple story. At the hour mentioned, three Negro women noticed two suspicious men sitting on a door step in the above locality. The women saw the two men making an apparent inspection of the building. As they told the story, they saw the men look over the fence and examine the window blinds, and they paid particular attention to the make-up of the building, which was a two-story affair. About that time Sergeant J.C. Aucoin and Officers Mora and J.D. Cantrell hove in sight. The women hailed them and described to them the suspicious actions of the two Negroes, who were still sitting on the step. The trio of bluecoats, on hearing the facts, at once crossed the street and accosted the men. The latter answered that they were waiting for a friend whom they were expecting. Not satisfied with this answer, the sergeant asked them where they lived, and they replied “down town”, but could not designate the locality. To other questions put by the officers the larger of the two Negroes replied that they had been in town just three days.

As this reply was made, the larger man sprang to his feet, and Patrolman Mora, seeing that he was about to run away, seized him. The Negro took a firm hold on the officer, and a scuffle ensued. Mora, noting that he was not being assisted by his brother officers, drew his billy and struck the Negro on the head. The blow had but little effect upon the man, for he broke away and started down the street. When about ten feet away, the Negro drew his revolver and opened fire on the officer, firing three or four shots. The third shot struck Mora in the right hip, and was subsequently found to have taken an upward course. Although badly wounded, Mora drew his pistol and returned the fire. At his third shot the Negro was noticed to stagger, but he did not fall. He continued his flight. At this moment Sergeant Aucoin seized the other Negro, who proved to be a youth, Leon Pierce. As soon as Officer Mora was shot he sank to the sidewalk, and the other officer ran to the nearest telephone, and sent in a call for the ambulance. Upon its arrival the wounded officer was placed in it and conveyed to the hospital. An examination by the house surgeon revealed the fact that the bullet had taken an upward course. In the opinion of the surgeon the wound was a dangerous one.

But the best proof of the fact that the officers accosted the two colored men and without any warrant or other justification attempted to arrest them, and did actually seize and begin to club one of them, is shown by Officer Mora’s own statement. The officer was wounded and had every reason in the world to make his side of the story as good as possible. His statement was made to a Picayune reporter and the same was published on the twenty-fifth inst., and is as follows:

I was in the neighborhood of Dryades and Washington Streets, with Sergeant Aucoin and Officer Cantrell, when three Negro women came up and told us that there were two suspicious-looking Negroes sitting on a step on Dryades Street, between Washington and Sixth. We went to the place indicated and found two Negroes. We interrogated them as to who they were, what they were doing and how long they had been here. They replied that they were working for some one and had been in town three days. At about this stage the larger of the two Negroes got up and I grabbed him. The Negro pulled, but I held fast, and he finally pulled me into the street. Here I began using my billet, and the Negro jerked from my grasp and ran. He then pulled a gun and fired. I pulled my gun and returned the fire, each of us firing about three shots. I saw the Negro stumble several times, and I thought I had shot him, but he ran away and I don’t know whether any of my shots took effect. Sergeant Aucoin in the meantime held the other man fast. The man was about ten feet from me when he fired, and the three Negresses who told us about the men stood away about twenty-five feet from the shooting.

Thus far in the proceeding the Monday night episode results in Officer Mora lying in the station wounded in the hip; Leonard Pierce, one of the colored men, locked up in the station, and Robert Charles, the other colored man, a fugitive, wounded in the leg and sought for by the entire police force of New Orleans. Not sought for, however, to be placed under arrest and given a fair trial and punished if found guilty according to the law of the land, but sought for by a host of enraged, vindictive and fearless officers, who were coolly ordered to kill him on sight. This order is shown by the Picayune of the twenty-sixth inst., in which the following statement appears:

In talking to the sergeant about the case, the captain asked about the Negro’s fighting ability, and the sergeant answered that Charles, though he called him Robinson then, was a desperate man, and it would be best to shoot him before he was given a chance to draw his pistol upon any of the officers.

This instruction was given before anybody had been killed, and the only evidence that Charles was a desperate man lay in the fact that he had refused to be beaten over the head by Officer Mora for sitting on a step quietly conversing with a friend. Charles resisted an absolutely unlawful attack, and a gun fight followed. Both Mora and Charles were shot, but because Mora was white and Charles was black, Charles was at once declared to be a desperado, made an outlaw, and subsequently a price put upon his head and the mob authorized to shoot him like a dog, on sight.

The New Orleans Picayune of Wednesday morning said:

But he has gone, perhaps to the swamps, and the disappointment of the bluecoats in not getting the murderer is expressed in their curses, each man swearing that the signal to halt that will be offered Charles will be a shot.

In that same column of the Picayune it was said:

Hundreds of policemen were about; each corner was guarded by a squad, commanded either by a sergeant or a corporal, and every man had the word to shoot the Negro as soon as he was sighted. He was a desperate black and would be given no chance to take more life.

Legal sanction was given to the mob or any man of the mob to kill Charles at sight by the Mayor of New Orleans, who publicly proclaimed a reward of two hundred and fifty dollars, not for the arrest of Charles, not at all, but the reward was offered for Charles’s body, “dead or alive” The advertisement was as follows:

Under the authority vested in me by law, I hereby offer, in the name of the city of New Orleans, $250 reward for the capture and delivery, dead or alive, to the authorities of the city, the body of the Negro murderer,

who, on Tuesday morning, July 24, shot and killed Police Captain John T. Day and Patrolman Peter J. Lamb, and wounded Patrolman August T. Mora.

Mayor

This authority, given by the sergeant to kill Charles on sight, would have been no news to Charles, nor to any colored man in New Orleans, who, for any purpose whatever, even to save his life, raised his hand against a white man. It is now, even as it was in the days of slavery, an unpardonable sin for a Negro to resist a white man, no matter how unjust or unprovoked the white man’s attack may be. Charles knew this, and knowing to be captured meant to be killed, he resolved to sell his life as dearly as possible.

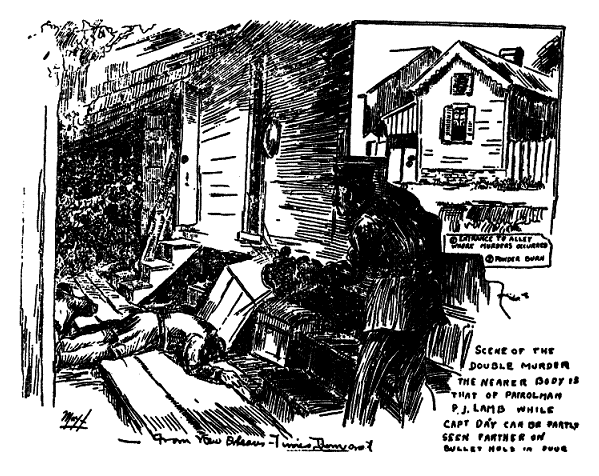

The next step in the terrible tragedy occurred between 2:30 and 5 o’clock Tuesday morning, about four hours after the affair on Dryades Street. The man hunt, which had been inaugurated soon after Officer Mora had been carried to the station, succeeded in running down Robert Charles, the wounded fugitive, and located him at 2023 4th Street. It was nearly 2 o’clock in the morning when a large detail of police surrounded the block with the intent to kill Charles on sight. Capt. Day had charge of the squad of police. Charles, the wounded man, was in his house when the police arrived, fully prepared, as results afterward showed, to die in his own home. Capt. Day started for Charles’s room. As soon as Charles got sight of him there was a flash, a report, and Day fell dead in his tracks. In another instant Charles was standing in the door, and seeing Patrolman Peter J. Lamb, he drew his gun, and Lamb fell dead. Two other officers, Sergeant Aucoin and Officer Trenchard, who were in the squad, seeing their comrades, Day and Lamb, fall dead, concluded to raise the siege, and both disappeared into an adjoining house, where they blew out their lights so that their cowardly carcasses could be safe from Charles’s deadly aim. The calibre of their courage is well shown by the fact that they concluded to save themselves from any harm by remaining prisoners in that dark room until daybreak, out of reach of Charles’s deadly rifle. Sergeant Aucoin, who had been so brave a few hours before when seeing the two colored men sitting on the steps, talking together on Dryades Street, and supposing that neither was armed, now showed his true calibre. Now he knew that Charles had a gun and was brave enough to use it, so he hid himself in a room two hours while Charles deliberately walked out of his room and into the street after killing both Lamb and Day. It is also shown, as further evidence of the bravery of some of New Orleans’ “finest”, that one of them, seeing Capt. Day fall, ran seven blocks before he stopped, afterwards giving the excuse that he was hunting for a patrol box.

At daybreak the officers felt safe to renew the attack upon Charles, so they broke into his room, only to find that — what they probably very well knew — he had gone. It appears that he made his escape by crawling through a hole in the ceiling to a little attic in his house. Here he found that he could not escape except by a window which led into an alley, which had no opening on 4th Street. He scaled the fence and was soon out of reach.

It was now 5 o’clock Tuesday morning, and a general alarm was given. Sergeant Aucoin and Corporal Trenchard, having received a new supply of courage by returning daylight, renewed their effort to capture the man that they had allowed to escape in the darkness. Citizens were called upon to participate in the man hunt and New Orleans was soon the scene of terrible excitement. Officers were present everywhere, and colored men were arrested on all sides upon the pretext that they were impertinent and “game niggers” An instance is mentioned in the Times-Democrat of the twenty-fifth and shows the treatment which unoffending colored men received at the hands of some of the officers. This instance shows Corporal Trenchard, who displayed such remarkable bravery on Monday night in dodging Charles’s revolver, in his true light. It shows how brave a white man is when he has a gun attacking a Negro who is a helpless prisoner. The account is as follows:

The police made some arrests in the neighborhood of the killing of the two officers. Mobs of young darkies gathered everywhere. These Negroes talked and joked about the affair, and many of them were for starting a race war on the spot. It was not until several of these little gangs amalgamated and started demonstrations that the police commenced to act. Nearly a dozen arrests were made within an hour, and everybody in the vicinity was in a tremor of excitement.

It was about 1 o’clock that the Negroes on Fourth Street became very noisy, and George Meyers, who lives on Sixth Street, near Rampart, appeared to be one of the prime movers in a little riot that was rapidly developing. Policeman Exnicios and Sheridan placed him under arrest, and owing to the fact that the patrol wagon had just left with a number of prisoners, they walked him toward St. Charles Avenue in order to get a conveyance to take him to the Sixth Precinct station.

A huge crowd of Negroes followed the officers and their prisoners. Between Dryades and Baronne, on Sixth, Corporal Trenchard met the trio. He had his pistol in his hand and he came on them running. The Negroes in the wake of the officers, and prisoner took to flight immediately. Some disappeared through gates and some over fences and into yards, for Trenchard, visibly excited, was waving his revolver in the air and was threatening to shoot. He joined the officers in their walk toward St. Charles Street, and the way he acted led the white people who were witnessing the affair to believe that his prisoner was the wanted Negro. At every step he would punch him or hit him with the barrel of his pistol, and the onlookers cried, “Lynch him!” “Kill him!” and other expressions until the spectators were thoroughly wrought up. At St. Charles Street, Trenchard desisted, and, calling an empty ice wagon, threw the Negro into the body of the vehicle and ordered Officer Exnicios to take him to the Sixth Precinct station.

The ride to the station was a wild one. Exnicios had all he could do to watch his prisoner. A gang climbed into the wagon and administered a terrible thrashing to the black en route. It took a half hour to reach the police station, for the mule that was drawing the wagon was not overly fast. When the station was reached a mob of nearly 200 howling white youths was awaiting it. The noise they made was something terrible. Meyers was howling for mercy before he reached the ground. The mob dragged him from the wagon, the officer with him. Then began a torrent of abuse for the unfortunate prisoner.

The station door was but thirty feet away, but it took Exnicios nearly five minutes to fight his way through the mob to the door. There were no other officers present, and the station seemed to be deserted. Neither the doorman nor the clerk paid any attention to the noise on the outside. As the result, the maddened crowd wrought their vengeance on the Negro. He was punched, kicked, bruised and torn. The clothes were ripped from his back, while his face after that few minutes was unrecognizable.

This was the treatment accorded and permitted to a helpless prisoner because he was black. All day Wednesday the man hunt continued. The excitement caused by the deaths of Day and Lamb became intense. The officers of the law knew they were trailing a man whose aim was deadly and whose courage they had never seen surpassed. Commenting upon the marksmanship of the man which the paper styled a fiend, the Times-Democrat of Wednesday said:

One of the extraordinary features of the tragedy was the marksmanship displayed by the Negro desperado. His aim was deadly and his coolness must have been something phenomenal. The two shots that killed Captain Day and Patrolman Lamb struck their victims in the head, a circumstance remarkable enough in itself, considering the suddenness and fury of the onslaught and the darkness that reigned in the alley way.

Later on Charles fired at Corporal Perrier, who was standing at least seventy-five yards away. The murderer appeared at the gate, took lightning aim along the side of the house, and sent a bullet whizzing past the officer’s ear. It was a close shave, and a few inches’ deflection would no doubt have added a fourth victim to the list.

At the time of the affray there is good reason to believe that Charles was seriously wounded, and at any event he had lost quantities of blood. His situation was as critical as it is possible to imagine, yet he shot like an expert in a target range. The circumstance shows the desperate character of the fiend, and his terrible dexterity with weapons makes him one of the most formidable monsters that has ever been loose upon the community.

Wednesday New Orleans was in the hands of a mob. Charles, still sought for and still defending himself, had killed four policemen, and everybody knew that he intended to die fighting. Unable to vent its vindictiveness and bloodthirsty vengeance upon Charles, the mob turned its attention to other colored men who happened to get in the path of its fury. Even colored women, as has happened many times before, were assaulted and beaten and killed by the brutal hoodlums who thronged the streets. The reign of absolute lawlessness began about 8 o’clock Wednesday night. The mob gathered near the Lee statue and was soon making its way to the place where the officers had been shot by Charles. Describing the mob, the Times-Democrat of Thursday morning says:

The gathering in the square, which numbered about 700, eventually became in a measure quiet, and a large, lean individual, in poor attire and with unshaven face, leaped upon a box that had been brought for the purpose, and in a voice that under no circumstances could be heard at a very great distance, shouted: “Gentlemen, I am the Mayor of Kenner” He did not get a chance for some minutes to further declare himself, for the voice of the rabble swung over his like a huge wave over a sinking craft. He stood there, however, wildly waving his arms and demanded a hearing, which was given him when the uneasiness of the mob was quieted for a moment or so.

“I am from Kenner, gentlemen, and I have come down to New Orleans tonight to assist you in teaching the blacks a lesson. I have killed a Negro before, and in revenge of the wrong wrought upon you and yours, I am willing to kill again. The only way that you can teach these Niggers a lesson and put them in their place is to go out and lynch a few of them as an object lesson. String up a few of them, and the others will trouble you no more. That is the only thing to do — kill them, string them up, lynch them! I will lead you, if you will but follow. On to the Parish Prison and lynch Pierce!”

They bore down on the Parish Prison like an avalanche, but the avalanche split harmlessly on the blank walls of the jail, and Remy Klock sent out a brief message: “You can’t have Pierce, and you can’t get in” Up to that time the mob had had no opposition, but Klock’s answer chilled them considerably. There was no deep-seated desperation in the crowd after all, only, that wild lawlessness which leads to deeds of cruelty, but not to stubborn battle. Around the corner from the prison is a row of pawn and second-hand shops, and to these the mob took like the ducks to the proverbial mill-pond, and the devastation they wrought upon Mr. Fink’s establishment was beautiful in its line.

Everything from breast pins to horse pistols went into the pockets of the crowd, and in the melee a man was shot down, while just around the corner somebody planted a long knife in the body of a little newsboy for no reason as yet shown. Every now and then a Negro would be flushed somewhere in the outskirts of the crowd and left beaten to a pulp. Just how many were roughly handled will never be known, but the unlucky thirteen had been severely beaten and maltreated up to a late hour, a number of those being in the Charity Hospital under the bandages and courtplaster of the doctors.

The first colored man to meet death at the hands of the mob was a passenger on a street car. The mob had broken itself into fragments after its disappointment at the jail, each fragment looking for a Negro to kill. The bloodthirsty cruelty of one crowd is thus described by the Times-Democrat:

“We will get a Nigger down here, you bet!” was the yelling boast that went up from a thousand throats, and for the first time the march of the mob was directed toward the downtown sections. The words of the rioters were prophetic, for just as Canal Street was reached a car on the Villere line came along.

“Stop that car!” cried half a hundred men. The advance guard, heeding the injunction, rushed up to the slowly moving car, and several, seizing the trolley, jerked it down.

“Here’s a Nigro!” said half a dozen men who sprang upon the car.

The car was full of passengers at the time, among them several women. When the trolley was pulled down and the car thrown in total darkness, the latter began to scream, and for a moment or so it looked as if the life of every person in the car was in peril, for some of the crowd with demoniacal yells of “There he goes!” began to fire their weapons indiscriminately. The passengers in the car hastily jumped to the ground and joined the crowd, as it was evidently the safest place to be.

“Where’s that Nigger?” was the query passed along the line, and with that the search began in earnest. The Negro, after jumping off the car, lost himself for a few moments in the crowd, but after a brief search he was again located. The slight delay seemed, if possible, only to whet the desire of the bloodthirsty crowd, for the reappearance of the Negro was the signal for a chorus of screams and pistol shots directed at the fugitive. With the speed of a deer, the man ran straight from the corner of Canal and Villere to Customhouse Street. The pursuers, closely following, kept up a running fire, but notwithstanding the fact that they were right at the Negro’s heels their aim was poor and their bullets went wide of the mark.

The Negro, on reaching Customhouse Street, darted from the sidewalk out into the middle of the street. This was the worst maneuver that he could have made, as it brought him directly under the light from an arc lamp, located on a nearby corner. When the Negro came plainly in view of the foremost of the closely following mob they directed a volley at him. Half a dozen pistols flashed simultaneously, and one of the bullets evidently found its mark, for the Negro stopped short, threw up his hands, wavered for a moment, and then started to run again. This stop, slight as it was, proved fatal to the Negro’s chances, for he had not gotten twenty steps farther when several of the men in advance of the others reached his side. A burly fellow, grabbing him with one hand, dealt him a terrible blow on the head with the other. The wounded man sank to the ground. The crowd pressed around him and began to beat him and stamp him. The men in the rear pressed forward and those beating the man were shoved forward. The half-dead Negro, when he was freed from his assailants, crawled over to the gutter. The men behind, however, stopped pushing when those in front yelled, “We’ve got him,” and then it was that the attack on the bleeding Negro was resumed. A vicious kick directed at the Negro’s head sent him into the gutter, and for a moment the body sank from view beneath the muddy, slimy water. “Pull him out; don’t let him drown,” was the cry, and instantly several of the men around the half-drowned Negro bent down and drew the body out. Twisting the body around they drew the head and shoulders up on the street, while from the waist down the Negro’s body remained under the water. As soon as the crowd saw that the Negro was still alive they again began to beat and kick him. Every few moments they would stop and striking matches look into the man’s face to see if he still lived. To better see if he was dead they would stick lighted matches to his eyes. Finally, believing he was dead they left him and started out to look for other Negroes. Just about this time some one yelled, “He ain’t dead,” and the men came back and renewed the attack. While the men were beating and pounding the prostrate form with stones and sticks a man in the crowd ran up, and crying, “I’ll fix the d—— Negro,” poked the muzzle of a pistol almost against the body and fired. This shot must have ended the man’s life, for he lay like a stone, and realizing that they were wasting energy in further attacks, the men left their victim lying in the street.

The same paper, on the same day, July 26, describes the brutal butchery of an aged colored man early in the morning:

Baptiste Philo, a Negro, seventy-five years of age, was a victim of mob violence at Kerlerec and North Peters Streets about 2:30 o’clock this morning. The old man is employed about the French Market, and was on his way there when he was met by a crowd and desperately shot. The old man found his way to the Third Precinct police station, where it was found that he had received a ghastly wound in the abdomen. The ambulance was summoned and he was conveyed to the Charity Hospital. The students pronounced the wound fatal after a superficial examination.

Mob rule continued Thursday, its violence increasing every hour, until 2 p.m., when the climax seemed to be reached. The fact that colored men and women had been made the victims of brutal mobs, chased through the streets, killed upon the highways and butchered in their homes, did not call the best element in New Orleans to active exertion in behalf of law and order. The killing of a few Negroes more or less by irresponsible mobs does not cut much figure in Louisiana. But when the reign of mob law exerts a depressing influence upon the stock market and city securities begin to show unsteady standing in money centers, then the strong arm of the good white people of the South asserts itself and order is quickly brought out of chaos.

It was so with New Orleans on that Thursday. The better element of the white citizens began to realize that New Orleans in the hands of a mob would not prove a promising investment for Eastern capital, so the better element began to stir itself, not for the purpose of punishing the brutality against the Negroes who had been beaten, or bringing to justice the murderers of those who had been killed, but for the purpose of saving the city’s credit. The Times-Democrat, upon this phase of the situation on Friday morning says:

When it became known later in the day that State bonds had depreciated from a point to a point and a half on the New York market a new phase of seriousness was manifest to the business community. Thinking men realized that a continuance of unchecked disorder would strike a body blow to the credit of the city and in all probability would complicate the negotiation of the forthcoming improvement bonds. The bare thought that such a disaster might be brought about by a few irresponsible boys, tramps and ruffians, inflamed popular indignation to fever pitch. It was all that was needed to bring to the aid of the authorities the active personal cooperation of the entire better element.

With the financial credit of the city at stake, the good citizens rushed to the rescue, and soon the Mayor was able to mobilize a posse of 1,000 willing men to assist the police in maintaining order, but rioting still continued in different sections of the city. Colored men and women were beaten, chased and shot whenever they made their appearance upon the street. Late in the night a most despicable piece of villainy occurred on Rousseau Street, where an aged colored woman was killed by the mob. The Times-Democrat thus describes, the murder:

Hannah Mabry, an old Negress, was shot and desperately wounded shortly after midnight this morning while sleeping in her home at No. 1929 Rousseau Street. It was the work of a mob, and was evidently well planned so far as escape was concerned, for the place was reached by police officers, and a squad of the volunteer police within a very short time after the reports of the shots, but not a prisoner was secured. The square was surrounded, but the mob had scattered in several directions, and, the darkness of the neighborhood aiding them, not one was taken.

At the time the mob made the attack on the little house there were also in it David Mabry, the sixty-two-year-old husband of the wounded woman; her son, Harry Mabry; his wife, Fannie, and an infant child. The young couple with their babe could not be found after the whole affair was over, and they either escaped or were hustled off by the mob. A careful search of the whole neighborhood was made, but no trace of them could be found.

The little place occupied by the Mabry family is an old cottage on the swamp side of Rousseau Street. It is furnished with slat shutters to both doors and windows. These shutters had been pulled off by the mob and the volleys fired through the glass doors. The younger Mabrys, father, mother and child, were asleep in the first room at the time. Hannah Mabry and her old husband were sleeping in the next room. The old couple occupied the same bed, and it is miraculous that the old man did not share the fate of his spouse.

Officer Bitterwolf, who was one of the first on the scene, said that he was about a block and a half away with Officers Fordyce and Sweeney. There were about twenty shots fired, and the trio raced to the cottage. They saw twenty or thirty men running down Rousseau Street. Chase was given and the crowd turned toward the river and scattered into several vacant lots in the neighborhood.

The volunteer police stationed at the Sixth Precinct had about five blocks to run before they arrived. They also moved on the reports of the firing, and in a remarkably short time the square was surrounded, but no one could be taken. As they ran to the scene they were assailed on every hand with vile epithets and the accusation of “Nigger lovers.”

Rousseau Street, where the cottage is situated, is a particularly dark spot, and no doubt the members of the mob were well acquainted with the neighborhood, for the officers said that they seemed to sink into the earth, so completely and quickly did they disappear after they had completed their work, which was complete with the firing of the volley.

Hannah Mabry was taken to the Charity Hospital in the ambulance, where it was found on examination that she had been shot through the right lung, and that the wound was a particularly serious one.

Her old husband was found in the little wrecked home well nigh distracted with fear and grief. It was he who informed the police that at the time of the assault the younger Mabrys occupied the front room. As he ran about the little home as well as his feeble condition would permit he severely lacerated his feet on the glass broken from the windows and door. He was escorted to the Sixth Precinct station, where he was properly cared for. He could not realize why his little family had been so murderously attacked, and was inconsolable when his wife was driven off in the ambulance piteously moaning in her pain.

The search for the perpetrators of the outrage was thorough, but both police and armed force of citizens had only their own efforts to rely on. The residents of the neighborhood were aroused by the firing, but they would give no help in the search and did not appear in the least concerned over the affair. Groups were on almost every doorstep, and some of them even jeered in a quiet way at the men who were voluntarily attempting to capture the members of the mob. Absolutely no information could be had from any of them, and the whole affair had the appearance of being the work of roughs who either lived in the vicinity, or their friends.

DEATH OF CHARLES

Friday witnessed the final act in the bloody drama begun by the three police officers, Aucoin, Mora and Cantrelle. Betrayed into the hands of the police, Charles, who had already sent two of his would-be murderers to their death, made a last stand in a small building, 1210 Saratoga Street, and, still defying his pursuers, fought a mob of twenty thousand people, single-handed and alone, killing three more men, mortally wounding two more and seriously wounding nine others. Unable to get to him in his stronghold, the besiegers set fire to his house of refuge. While the building was burning Charles was shooting, and every crack of his death-dealing rifle added another victim to the price which he had placed upon his own life. Finally, when fire and smoke became too much for flesh and blood to stand, the long sought for fugitive appeared in the door, rifle in hand, to charge the countless guns that were drawn upon him. With a courage which was indescribable, he raised his gun to fire again, but this time it failed, for a hundred shots riddled his body, and he fell dead face fronting to the mob. This last scene in the terrible drama is thus described in the Times-Democrat of July 26:

Early yesterday afternoon, at 3 o’clock or thereabouts, Police Sergeant Gabriel Porteus was instructed by Chief Gaster to go to a house at No. 1210 Saratoga Street, and search it for the fugitive murderer, Robert Charles. A private “tip” had been received at the headquarters that the fiend was hiding somewhere on the premises.

Sergeant Porteus took with him Corporal John R. Lally and Officers Zeigel and Essey. The house to which they were directed is a small, double frame cottage, standing flush with Saratoga Street, near the corner of Clio. It has two street entrances and two rooms on each side, one in front and one in the rear. It belongs to the type of cheap little dwellings commonly tenanted by Negroes.

Sergeant Porteus left Ziegel and Essey to guard the outside and went with Corporal Lally to the rear house, where he found Jackson and his wife in the large room on the left. What immediately ensued is only known by the Negroes. They say the sergeant began to question them about their lodgers and finally asked them whether they knew anything about Robert Charles. They strenuously denied all knowledge of his whereabouts.

The Negroes lied. At that very moment the hunted and desperate murderer lay concealed not a dozen feet away. Near the rear, left-hand corner of the room is a closet or pantry, about three feet deep, and perhaps eight feet long. The door was open and Charles was crouching, Winchester in hand, in the dark further end.

Near the closet door was a bucket of water, and Jackson says that Sergeant Porteous walked toward it to get a drink. At the next moment a shot rang out and the brave officer fell dead. Lally was shot directly afterward. Exactly how and where will never be known, but the probabilities are that the black fiend sent a bullet into him before he recovered from his surprise at the sudden onslaught. Then the murderer dashed out of the back door and disappeared.

The neighborhood was already agog with the tragic events of the two preceding days, and the sound of the shots was a signal for wild and instant excitement. In a few moments a crowd had gathered and people were pouring in by the hundred from every point of the compass. Jackson and his wife had fled and at first nobody knew what had happened, but the surmise that Charles had recommenced his bloody work was on every tongue and soon some of the bolder found their way to the house in the rear. There the bleeding forms of the two policemen told the story.

Lally was still breathing, and a priest was sent for to administer the last rites. Father Fitzgerald responded, and while he was bending over the dying man the outside throng was rushing wildly through the surrounding yards and passageways searching for the murderer. “Where is he?” “What has become of him,” were the questions on every lip.

Suddenly the answer came in a shot from the room directly overhead. It was fired through a window facing Saratoga Street, and the bullet struck down a young man named Alfred J. Bloomfield, who was standing in the narrow passage-way between the two houses. He fell on his knees and a second bullet stretched him dead.

When he fled from the closet Charles took refuge in the upper story of the house. There are four windows on that floor, two facing toward Saratoga Street and two toward Rampart. The murderer kicked several breaches in the frail central partition, so he could rush from side to side, and like a trapped beast, prepared to make his last stand.

Nobody had dreamed that he was still in the house, and when Bloomfield was shot there was a headlong stampede. It was some minutes before the exact situation was understood. Then rifles and pistols began to speak, and a hail of bullets poured against the blind frontage of the old house. Every one hunted some coign of vantage, and many climbed to adjacent roofs. Soon the glass of the four upper windows was shattered by flying lead. The fusillade sounded like a battle, and the excitement upon the streets was indescribable.

Throughout all this hideous uproar Charles seems to have retained a certain diabolical coolness. He kept himself mostly out of sight, but now and then he thrust the gleaming barrel of his rifle through one of the shattered window panes and fired at his besiegers. He worked the weapon with incredible rapidity, discharging from three to five cartridges each time before leaping back to a place of safety. These replies came from all four windows indiscriminately, and showed that he was keeping a close watch in every direction. His wonderful marksmanship never failed him for a moment, and when he missed it was always by the narrowest margin only.

On the Rampart Street side of the house there are several sheds, commanding an excellent range of the upper story. Detective Littleton, Andrew Van Kuren of the Workhouse force and several others climbed upon one of these and opened fire on the upper windows, shooting whenever they could catch a glimpse of the assassin. Charles responded with his rifle, and presently Van Kuren climbed down to find a better position. He was crossing the end of the shed when he was killed.

Another of Charles’s bullets found its billet in the body of Frank Evans, an ex-member of the police force. He was on the Rampart Street side firing whenever he had an opportunity. Officer J.W. Bofill and A.S. Leclerc were also wounded in the fusillade.

While the events thus briefly outlined were transpiring time was a-wing, and the cooler headed in the crowd began to realize that some quick and desperate expedient must be adopted to insure the capture of the fiend and to avert what might be a still greater tragedy than any yet enacted. For nearly two hours the desperate monster had held his besiegers at bay, darkness would soon be at hand and no one could predict what might occur if he made a dash for liberty in the dark.

At this critical juncture it was suggested that the house be fired. The plan came as an inspiration, and was adopted as the only solution of the situation. The wretched old rookery counted for nothing against the possible continued sacrifice of human life, and steps were immediately taken to apply the torch. The fire department had been summoned to the scene soon after the shooting began; its officers were warned to be ready to prevent a spread of the conflagration, and several men rushed into the lower right-hand room and started a blaze in one corner.

They first fired an old mattress, and soon smoke was pouring out in dense volumes. It filled the interior of the ramshackle structure, and it was evident that the upper story would soon become untenable. An interval of tense excitement followed, and all eyes were strained for a glimpse of the murderer when he emerged.

Then came the thrilling climax. Smoked out of his den, the desperate fiend descended the stairs and entered the lower room. Some say he dashed into the yard, glaring around vainly for some avenue of escape; but, however that may be, he was soon a few moments later moving about behind the lower windows. A dozen shots were sent through the wall in the hope of reaching him, but he escaped unscathed. Then suddenly the door on the right was flung open and he dashed out. With head lowered and rifle raised ready to fire on the instant, Charles dashed straight for the rear door of the front cottage. To reach it he had to traverse a little walk shaded by a vineclad arbor. In the back room, with a cocked revolver in his hand, was Dr. C.A. Noiret, a young medical student, who was aiding the citizens’ posse. As he sprang through the door Charles fired a shot, and the bullet whizzed past the doctor’s head. Before it could be repeated Noiret’s pistol cracked and the murderer reeled, turned half around and fell on his back. The doctor sent another ball into his body as he struck the floor, and half a dozen men, swarming into the room from the front, riddled the corpse with bullets.

Private Adolph Anderson of the Connell Rifles was the first man to announce the death of the wretch. He rushed to the street door, shouted the news to the crowd, and a moment later the bleeding body was dragged to the pavement and made the target of a score of pistols. It was shot, kicked and beaten almost out of semblance to humanity....

The limp dead body was dropped at the edge of the sidewalk and from there dragged to the muddy roadway by half a hundred hands. There in the road more shots were fired into the body. Corporal Trenchard, a brother-in-law of Porteus, led the shooting into the inanimate clay. With each shot there was a cheer for the work that had been done and curses and imprecations on the inanimate mass of riddled flesh that was once Robert Charles.

Cries of “Burn him! Burn him!” were heard from Clio Street all the way to Erato Street, and it was with difficulty that the crowd was restrained from totally destroying the wretched dead body. Some of those who agitated burning even secured a large vessel of kerosene, which had previously been brought to the scene for the purpose of firing Charles’s refuge, and for a time it looked as though this vengeance might be wreaked on the body. The officers, however, restrained this move, although they were powerless to prevent the stamping and kicking of the body by the enraged crowd.

After the infuriated citizens had vented their spleen on the body of the dead Negro it was loaded into the patrol wagon. The police raised the body of the heavy black from the ground and literally chucked it into the space on the floor of the wagon between the seats. They threw it with a curse hissed more than uttered and born of the bitterness which was rankling in their breasts at the thought of Charles having taken so wantonly the lives of four of the best of their fellow-officers.

When the murderer’s body landed in the wagon it fell in such a position that the hideously mutilated head, kicked, stamped and crushed, hung over the end.

As the wagon moved off, the followers, who were protesting against its being carried off, declaring that it should be burned, poked and struck it with sticks, beating it into such a condition that it was utterly impossible to tell what the man ever looked like.

As the patrol wagon rushed through the rough street, jerking and swaying from one side of the thoroughfare to the other, the gory, mud-smeared head swayed and swung and jerked about in a sickening manner, the dark blood dripping on the steps and spattering the body of the wagon and the trousers of the policemen standing on the step.

MOB BRUTALITY

The brutality of the mob was further shown by the unspeakable cruelty with which it beat, shot and stabbed to death an unoffending colored man, name unknown, who happened to be walking on the street with no thought that he would be set upon and killed simply because he was a colored man. The Times-Democrat’s description of the outrage is as follows:

While the fight between the Negro desperado and the citizens was in progress yesterday afternoon at Clio and Saratoga Streets another tragedy was being enacted downtown in the French quarter, but it was a very one-sided affair. The object of the white man’s wrath was, of course, a Negro, but, unlike Charles, he showed no fight, but tried to escape from the furious mob which was pursuing him, and which finally put an end to his existence in a most cruel manner.

The Negro, whom no one seemed to know — at any rate no one could be found in the vicinity of the killing who could tell who he was — was walking along the levee, as near as could be learned, when he was attacked by a number of white longshoremen or screwmen. For what reason, if there was any reason other than the fact that he was a Negro, could not be learned, and immediately they pounced upon him he broke ground and started on a desperate run for his life.

The hunted Negro started off the levee toward the French Vegetable Market, changed his course out the sidewalk toward Gallatin Street. The angry, yelling mob was close at his heels, and increasing steadily as each block was traversed. At Gallatin Street he turned up that thoroughfare, doubled back into North Peters Street and ran into the rear of No. 1216 of that street, which is occupied by Chris Reuter as a commission store and residence.

He rushed frantically through the place and out on to the gallery on the Gallatin Street side. From this gallery he jumped to the street and fell flat on his back on the sidewalk. Springing to his feet as soon as possible, with a leaden, hail fired by the angry mob whistling about him, he turned to his merciless pursuers in an appealing way, and, throwing up one hand, told them not to shoot any more, that they could take him as he was.

But the hail of lead continued, and the unfortunate Negro finally dropped to the sidewalk, mortally wounded. The mob then rushed upon him, still continuing the fusillade, and upon reaching his body a number of Italians, who had joined the howling mob, reached down and stabbed him in the back and buttock with big knives. Others fired shots into his head until his teeth were shot out, three shots having been fired into his mouth. There were bullet wounds all over his body.

Others who witnessed the affair declared that the man was fired at as he was running up the stairs leading to the living apartments above the store, and that after jumping to the sidewalk and being knocked down by a bullet he jumped up and ran across the street, then ran back and tried to get back into the commission store. The Italians, it is said, were all drunk, and had been shooting firecrackers. Tiring of this, they began shooting at Negroes, and when the unfortunate man who was killed ran by they joined in the chase.

No one was arrested for the shooting, the neighborhood having been deserted by the police, who were sent up to the place where Charles was fighting so desperately. No one could or would give the names of any of those who had participated in the chase and the killing, nor could any one be found who knew who the Negro was. The patrol wagon was called and the terribly mutilated body sent to the morgue and the coroner notified.

The murdered Negro was copper colored, about 5 feet 11 inches in height, about 35 years of age, and was dressed in blue overalls and a brown slouch hat. At 10:30 o’clock the vicinity of the French Market was very quiet. Squads of special officers were patrolling the neighborhood, and there did not seem to be any prospects of disorder.

During the entire time the mob held the city in its hands and went about holding up street cars and searching them, taking from them colored men to assault, shoot and kill, chasing colored men upon the public square, through alleys and into houses of anybody who would take them in, breaking into the homes of defenseless colored men and women and beating aged and decrepit men and women to death, the police and the legally constituted authorities showed plainly where their sympathies were, for in no case reported through the daily papers does there appear the arrest, trial and conviction of one of the mob for any of the brutalities which occurred. The ringleaders of the mob were at no time disguised. Men were chased, beaten and killed by white brutes, who boasted of their crimes, and the murderers still walk the streets of New Orleans, well known and absolutely exempt from prosecution. Not only were they exempt from prosecution by the police while the town was in the hands of the mob, but even now that law and order is supposed to resume control, these men, well known, are not now, nor ever will be, called to account for the unspeakable brutalities of that terrible week. On the other hand, the colored men who were beaten by the police and dragged into the station for purposes of intimidation, were quickly called up before the courts and fined or sent to jail upon the statement of the police. Instances of Louisiana justice as it is dispensed in New Orleans are here quoted from the Times-Democrat of July 26:

Justice Dealt Out to Folk Who Talked Too Much

All the Negroes and whites who were arrested in the vicinity of Tuesday’s tragedy had a hard time before Recorder Hughes yesterday. Lee Jackson was the first prisoner, and the evidence established that he made his way to the vicinity of the crime and told his Negro friends that he thought a good many more policemen ought to be killed. Jackson said he was drunk when he made the remark. He was fined $25 or thirty days.

John Kennedy was found wandering about the street Tuesday night with an open razor in his hand, and he was given $25 or thirty days.

Edward McCarthy, a white man, who arrived only four days since from New York, went to the scene of the excitement at the corner of Third and Rampart Streets, and told the Negroes that they were as good as any white man. This remark was made by McCarthy, as another white man said the Negroes should be lynched. McCarthy told the recorder that he considered a Negro as good as a white in body and soul. He was fined $25 or thirty days.

James Martin, Simon Montegut, Eddie McCall, Alex Washington and Henry Turner were up for failing to move on. Martin proved that he was at the scene to assist the police and was discharged. Montegut, being a cripple, was also released, but the others were fined $25 or thirty days each.

Eddie Williams for refusing to move on was given $25 or thirty days.

Matilda Gamble was arrested by the police for saying that two officers were killed and it was a pity more were not shot. She was given $25 or thirty days.

INSOLENT BLACKS

“Recorder Hughes received Negroes in the first recorder’s office yesterday morning in a way that they will remember for a long time, and all of them were before the magistrate for having caused trouble through incendiary remarks concerning the death of Captain Day and Patrolman Lamb.”

“Lee Jackson was before the recorder and was fined $25 or thirty days. He was lippy around where the trouble happened Tuesday morning, and some white men punched him good and hard and the police took him. Then the recorder gave him a dose, and now he is in the parish prison.”

“John Kennedy was another black who got into trouble. He said that the shooting of the police by Charles was a good thing, and for this he was pounded. Patrolman Lorenzo got him and saved him from being lynched, for the black had an open razor. He was fined $25 or thirty days.”

“Edward McCarthy, a white man, mixed up with the crowd, and an expression of sympathy nearly cost him his head, for some whites about started for him, administering licks and blows with fists and umbrellas. The recorder fined him $25 or thirty days. He is from New York.”

“Then James Martin, a white man, and Simon Montegut, Eddie Call, Henry Turner and Alex Washington were before the magistrate for having failed to move on when the police ordered them from the square where the bluecoats were Tuesday, waiting in the hope of catching Charles. All save Martin and Montegut were fined.”

“Eddie Williams, a little Negro who was extremely fresh with the police, was fined $10 or ten days.”

SHOCKING BRUTALITY

The whole city was at the mercy of the mob and the display of brutality was a disgrace to civilization. One instance is described in the Picayune as follows:

A smaller party detached itself from the mob at Washington and Rampart Streets, and started down the latter thoroughfare. One of the foremost spied a Negro, and immediately there was a rush for the unfortunate black man. With the sticks they had torn from fences on the line of march the young outlaws attacked the black and clubbed him unmercifully, acting more like demons than human beings. After being severely beaten over the head, the Negro started to run with the whole gang at his heels. Several revolvers were brought into play and pumped their lead at the refugee. The Negro made rapid progress and took refuge behind the blinds of a little cottage in Rampart Street, but he had been seen, and the mob hauled him from his hiding place and again commenced beating him. There were more this time, some twenty or thirty, all armed with sticks and heavy clubs, and under their incessant blows the Negro could not last long. He begged for mercy, and his cries were most pitiful, but a mob has no heart, and his cries were only answered with more blows.

“For God’s sake, boss, I ain’t done nothin’. Don’t kill me. I swear I ain’t done nothin’.”

The white brutes turned

of the black wretch and the drubbing continued. The cries subsided into moans, and soon the black swooned away into unconsciousness. Still not content with their heartless work, they pulled the Negro out and kicked him into the gutter. For the time those who had beaten the black seemed satisfied and left him groaning in the gutter, but others came up, and, regretting that they had not had a hand in the affair, they determined to evidence their bravery to their fellows and beat the man while he was in the gutter, hurling rocks and stones at his black form. One thoughtless white brute, worse even than the black slayer of the police officers, thought to make himself a hero in the eyes of his fellows and fired his revolver repeatedly into the helpless wretch. It was dark and the fellow probably aimed carelessly. After firing three or four shots he also left without knowing what extent of injury he inflicted on the black wretch who was left lying in the gutter.

MURDER ON THE LEVEE

One part of the crowd made a raid on the tenderloin district, hoping to find there some belated Negro for a sacrifice. They were urged on by the white prostitutes, who applauded their murderous mission. Says an account:

The red light district was all excitement. Women — that is, the white women — were out on their stoops and peeping over their galleries and through their windows and doors, shouting to the crowd to go on with their work, and kill Negroes for them.

“Our best wishes, boys,” they encouraged; and the mob answered with shouts, and whenever a Negro house was sighted a bombardment was started on the doors and windows.

No colored men were found on the streets until the mob reached Custom House Place and Villiers Streets. Here a victim was found and brutally put to death. The Picayune description is as follows:

Some stragglers had run a Negro into a car at the corner of Bienville and Villere Streets. He was seeking refuge in the conveyance, and he believed that the car would not be stopped and could speed along. But the mob determined to stop the car, and ordered the motorman to halt. He put on his brake. Some white men were in the car.

“Get out, fellows,” shouted several of the mob.

“All whites fall out,” was the second cry, and the poor Negro understood that it was meant that he should stay in the car.

He wanted to save his life. The poor fellow crawled under the seats. But some one in the crowd saw him and yelled that he was hiding. Two or three men climbed through the windows with their pistols; others jumped over the motorman’s board, and dozens tumbled into the rear of the car. Big, strong hands got the Negro by the shirt. He was dragged out of the conveyance, and was pushed to the street. Some fellow ran up and struck him with a club. The blow was heavy, but it did not fell him, and the Negro ran toward Canal Street, stealing along the wall of the Tulane Medical Building. Fifty men ran after him, caught the poor fellow and hurried him back into the crowd. Fists were aimed at him, then clubs went upon his shoulders, and finally the black plunged into the gutter.

A gun was fired, and the Negro, who had just gotten to his feet, dropped again. He tried to get up, but a volley was sent after him, and in a little while he was dead.

The crowd looked on at the terrible work. Then the lights in the houses of ill-fame began to light up again, and women peeped out of the blinds. The motorman was given the order to go on. The gong clanged and the conveyance sped out of the way. For half an hour the crowd held their place at the corner, then the patrol wagon came and the body was picked up and hurried to the morgue.

Coroner Richard held an autopsy on the body of the Negro who was forced out of car 98 of the Villere line and shot down. It was found that he was wounded four times, the most serious wound being that which struck him in the right side, passing through the lungs, and causing hemorrhages, which brought about death.

Nobody tried to identify the poor fellow and his name is unknown.

A VICTIM IN THE MARKET

Soon after the murder of the man on the street car many of the same mob marched down to the market place. There they found a colored market man named Louis Taylor, who had gone to begin his early morning’s work. He was at once set upon by the mob and killed. The Picayune account says:

Between 1 and 2 o’clock this morning a mob of several hundred men and boys, made up of participants in many of the earlier affairs, marched on the French Market. Louis Taylor, a Negro vegetable carrier, who is about thirty years of age, was sitting at the soda water stand. As soon as the mob saw him fire was opened and the Negro took to his heels. He ran directly into another section of the mob and any number of shots were fired at him. He fell, face down, on the floor of the market.

The police in the neighborhood rallied hurriedly and found the victim of mob violence seemingly lifeless. Before they arrived the Negro had been beaten severely about the head and body. The ambulance was summoned and Taylor was carried to the charity hospital, where it was found that he had been shot through the abdomen and arm. The examination was a hurried one, but it sufficed to show that Taylor was mortally wounded.

After shooting Taylor the members of the mob were pluming themselves on their exploit. “The Nigger was at the soda water stand and we commenced shooting him,” said one of the rioters. “He put his hands up and ran, and we shot until he fell. I understand that he is still alive. If he is, he is a wonder. He was certainly shot enough to be killed.”

The members of the mob readily admitted that they had taken part in the assaults which marked the earlier part of the evening.

“We were up on Jackson Avenue and killed a Nigger on Villere Street. We came down here, saw a nigger and killed him, too.” This was the way they told the story.

“Boys, we are out of ammunition,” said someone.

“Well, we will keep on like we are, and if we can’t get some before morning, we will take it. We have got to keep this thing up, now we have started.”

This declaration was greeted by a chorus of applauding yells, and the crowd started up the levee. Half of the men in the crowd, and they were all of them young, were drunk.

Taylor, when seen at the charity hospital, was suffering greatly, and presented a pitiable spectacle. His clothing was covered with blood, and his face was beaten almost into a pulp. He said that he had gone to the market to work and was quietly sitting down when the mob came and began to fire on him. He was not aware at first that the crowd was after him. When he saw its purpose he tried to run, but fell. He didn’t know any of the men in the crowd. There is hardly a chance that Taylor will recover.

The police told the crowd to move on, but no attempt was made to arrest anyone.

A GRAY-HAIRED VICTIM

The bloodthirsty barbarians, having tasted blood, continued their hunt and soon ran across an old man of seventy-five years. His life had been spent in hard work about the French market, and he was well known as an unoffending, peaceable and industrious old man.

But that made no difference to the mob. He was a Negro, and with a fiendishness that was worse than that of cannibals they beat his life out. The report says:

There was another gang of men parading the streets in the lower part of the city, looking for any stray Negro who might be on the streets. As they neared the corner of Dauphine and Kerlerec, a square below Esplanade Avenue, they came upon Baptiste Thilo, an aged Negro, who works in the French Market.

Thilo for years has been employed by the butchers and fish merchants to carry baskets from the stalls to the wagons, and unload the wagons as they arrive in the morning. He was on his way to the market, when the mob came upon him. One of the gang struck the old Negro, and as he fell, another in the crowd, supposed to be a young fellow, fired a shot. The bullet entered the body just below the right nipple.

As the Negro fell the crowd looked into his face and they discovered then that the victim was very old. The young man who did the shooting said: “Oh, he is an old Negro. I’m sorry that I shot him.”

This is all the old Negro received in the way of consolation.

He was left where he fell, but later staggered to his feet and made his way to the third precinct station. There the police summoned the ambulance and the students pronounced the wound very dangerous. He was carried to the hospital as rapidly as possible.

There was no arrest.

Just before daybreak the mob found another victim. He, too, was on his way to market, driving a meat wagon. But little is told of his treatment, nothing more than the following brief statement:

At nearly 3 o’clock this morning a report was sent to the Third Precinct station that a Negro was lying on the sidewalk at the corner of Decatur and St. Philip. The man had been pulled off of a meat wagon and riddled with bullets.

When the police arrived he was insensible and apparently dying. The ambulance students attended the Negro and pronounced the wounds fatal.

There was nothing found which would lead to the discovery of his identity.

FUN IN GRETNA

If there are any persons so deluded as to think that human life in the South is valued any more than the life of a brute, he will be speedily undeceived by reading the accounts of unspeakable barbarism committed by the mob in and around New Orleans. In no other civilized country in the world, nay, more, in no land of barbarians would it be possible to duplicate the scenes of brutality that are reported from New Orleans. In the heat of blind fury one might conceive how a mad mob might beat and kill a man taken red-handed in a brutal murder. But it is almost past belief to read that civilized white people, men who boast of their chivalry and blue blood, actually had fun in beating, chasing and shooting men who had no possible connection with any crime.

But this actually happened in Gretna, a few miles from New Orleans. In its description of the scenes of Tuesday night, the Picayune mentions the brutal chase of several colored men whom the mob sought to kill. In the instances mentioned, the paper said:

Gretna had its full share of excitement between 8 and 11 o’clock last night, in connection with a report that spread through the town that a Negro resembling the slayer of Police Captain Day, of New Orleans, had been seen on the outskirts of the place.

It is true that a suspicious-looking Negro was observed by the residents of Madison and Amelia Streets lurking about the fences of that neighborhood just after dark, and shortly before 8 o’clock John Fist, a young white man, saw the Negro on Fourth Street. He followed the darkey a short distance, and, coming upon Robert Moore, who is known about town as the “black detective,” Fist pointed the Negro out and Moore at once made a move toward the stranger. The latter observed Moore making in his direction, and, without a word, he sped in the direction of the Brooklyn pasture, Moore following and firing several shots at him. In a few minutes a half hundred white men, including Chief of Police Miller, Constable Dannenhauer, Patrolman Keegan and several special officers, all well-armed, joined in the chase, but in the darkness the Negro escaped.

Just as the pursuing party reached town again, two of the residents of Lafayette Avenue, Peter Leson and Robert Henning, reported that they had just chased and shot at a Negro, who had been seen in the yard of the former’s house. They were positive the Negro had not escaped from the square. Their report was enough to set the appetite of the crowd on edge, and the square was quickly surrounded, while several dozens of men, armed with lanterns and revolvers, made a search of every yard and under every house in the square. No Negro was found.

The crowd of armed men was constantly swelling, and at 10 o’clock it had reached the proportions of a small army. At 10:30 o’clock an outbound freight train is due to pass through Gretna on the Texas and Pacific Road, and the crowd, believing that Captain Day’s slayer might be aboard one of the cars attempting to leave the scene of his crime, resolved to inspect the train. As the train stopped at the Madison Street crossing the engineer was requested to pull very slowly through the town, in order that the trucks of the cars might be examined. There was a string of armed men on each side of the railroad track and in a few moments a Negro was espied riding between two cars. A half dozen weapons were pointed at him and he was ordered to come out. He sprang out with alacrity and was pounced upon almost before he reached the ground. Robert Moore grabbed him and pushed an ugly-looking Derringer under his nose and the Negro threw up both hands. Constable Dannenhauer and Patrolman Keegan took charge of him and hustled him off to jail, where he was locked up. The Negro does not at all resemble Robert Charles, but it was best for his sake that he was placed under lock and key. The crowd was not in a humor to let any Negro pass muster last night. The prisoner gave his name as Luke Wallace.

But now came the real excitement. The train had slowed down almost to a standstill, in the very heart of town. Somebody shouted: “There he goes, on top of the train!” And sure enough, somebody was going. It was a Negro, too, and he was making a bee-line for the front end of the train. A veritable shower of bullets, shot and rifle balls greeted the flying form, but on it sped. The locomotive had stopped in the middle of the square between La voisier and Newton Streets, and the Negro, flying with the speed of the wind along the top of the cars, reached the first car of the train and jumped to the tender and then into the cab. As he did several white men standing at the locomotive made a rush into the cab. The Negro sprang swiftly out of the other side, on to the sidewalk. But there were several more men, and as he realized that he was rushing right into their arms he made a spring to leap over the fence of Mrs. Linden’s home, on the wood side of the track. Before the Negro got to the top one white man had hold of his legs, while another rushed up, pistol in hand. The man who was holding the darkey’s legs was jostled out of the way and the man with the pistol, standing directly beneath the Negro, sent two bullets at him.

There was a wild scramble, and the vision of a fleeing form in the Linden yard, but that was the last seen of the black man. The yard was entered and searched, and neighboring yards were also searched, but not even the trace of blood was found. It is almost impossible to believe that the Negro was not wounded, for the man who fired at him held the pistol almost against the Negro’s body.

The shots brought out almost everybody — white — in town, and though there was nothing to show for the exciting work, except the arrest of the Negro, who doesn’t answer the description of the man wanted, Gretna’s male population had its little fan and felt amply repaid for all the trouble it was put to, and all the ammunition it wasted.

BRUTALITY IN NEW ORLEANS