Governor J. Madison Wells,

President Andrew Johnson,

Howell, R. K., et al.

“The New Orleans Riot.”

THE NEW ORLEANS RIOT.

CALLING OF THE

CONVENTION.

The loyal people of Louisiana, following the example of those of Tennessee, prepared to adopt the amendment to the Constitution proposed by the Thirty-Ninth Congress, and to that end the President pro tem. of the convention of 1864, known as the Lincoln Convention, issued the following call:

PROCLAMATION.

By R. K. Howell, President pro tem. of the Convention for the Revision and Amendment of the Constitution of Louisiana.

- Whereas, by the wise, just, and patriotic policy developed by the Congress now in session, it is essential that the organic law of the State of Louisiana should be revised and amended, so as to form a civil government in this State in harmony with the General Government, establish impartial justice, insure domestic tranquility, secure the blessings of liberty to all citizens alike, and restore the State to a proper and permanent position in the great Union of States, with ample guarantees against future disturbance of that Union; and

- Whereas it is provided by resolutions adopted on the 25th day of July, 1864, by the Convention for the Revision and Amendment of the Constitution of Louisiana, that when said convention adjourns, it shall be at the call of the President, whose duty it shall be to reconvoke the convention for any cause; and that he shall also, in that case, call upon the proper officers of the State to cause elections to be held to fill any vacancies that may exist in the convention, in parishes where the same may be practicable; and

- Whereas, further, it is important that the proposed amendment to the Constitution of the United States should be acted on in this State with the shortest delay practicable; and

- Whereas, at a meeting held in New Orleans, on the 26th of June, 1866, the members of said convention recognized the existence of the contingency provided for in said resolutions, expressed their belief that the wishes and interests of the loyal people of this State demand the reassembling of the said convention, and requested and duly authorized the undersigned to act as President pro tem., for the purpose of reconvoking said convention, and, in conjunction with his excellency the Governor of the State, to issue the requisite proclamations reconvoking said convention and ordering the necessary elections as soon as possible:

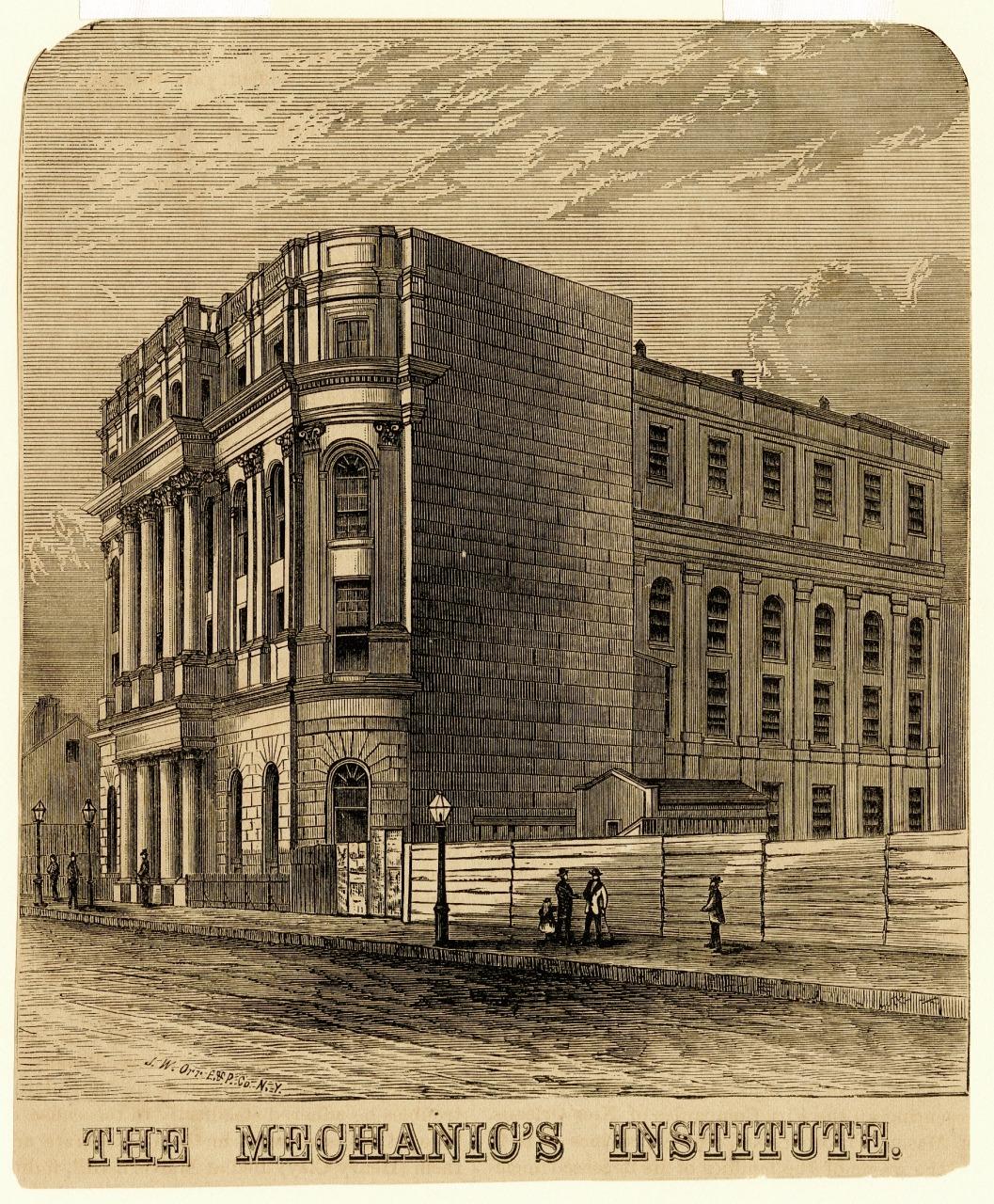

- Now, therefore, I, Rufus K. Howell, President pro tem. of the convention, as aforesaid, by virtue of the power and authority thus conferred on me, and in pursuance of the aforesaid resolutions of adjournment, do issue this my proclamation reconvoking the said “Convention for the Revision and Amendment of the Constitution of Louisiana;” and I do hereby notify and request all the delegates to said convention to assemble in the hall of the House of Representatives, Mechanics’ Institute building, in the city of New Orleans, on the fifth Monday, (thirtieth day) of July, 1866, at the hour of 12 o’clock m.; and I do further call upon his excellency the Governor of this State to issue the necessary writs of election to elect delegates to the said convention, in parishes not now represented therein.

President pro tem.

Attest: John E. Neelis,

Secretary.

As will be seen by the terms of this proclamation, the convention had adjourned in July, 1864, to meet at the call of the President, whose duty it was made to reconvoke the body and to call upon the State officers to cause elections to be held to fill vacancies whenever necessity required it. The actual president, E. H. Durell, being of the political persuasion of those who met in Philadelphia on August 14, 1866, and therefore agreeing with the President of the United States in his hostility to the constitutional amendment, refused to act. In consequence of this, on June 26, 1866, at a meeting of the convention called by prominent members, R. K. Howell, who issued the foregoing proclamation, was elected in his stead.

Pursuant to this proclamation, the Governor, J. Madison Wells, at once issued his writs of election to fill vacancies.

This movement seems to have alarmed the friends of President Johnson in Louisiana, and induced them to resort to measures of prevention similar to those unsuccessfully tried in Tennessee. It would not do to let a second of the States lately in rebellion consent to the terms of readmission so early and with such apparent cordiality. The following correspondence will show the initiatory steps taken to prevent so disastrous an overthrow to “my policy” in Louisiana:

War Department, July 28, 1866.

To His Excellency Governor Wells:

I have been advised that you have issued a proclamation convening the convention elected in 1864. Please inform me under and by what authority this has been done, and by what authority this convention can assume to represent the whole people of the State of Louisiana.

(Signed) Andrew Johnson.

STATE OF LOUISIANA.

Executive Department,

New Orleans,

July 28, 1866.

To His Excellency Andrew Johnson,

President of the United States:

Your telegram is received. I have not issued any order convening the convention of 1864. The convention was convened by the president of that body, by virtue of a resolution authorizing him to do so, and in that event for him to call on the proper officers of the State to issue writs of election for delegates in unrepresented parishes. My proclamation was issued in response to that call. As soon as vacancies can be ascertained, they will be filled; and then the whole State will be represented in the convention.

(Signed)

J. Madison Wells,

Governor.

The power by which the President calls upon the Governor to produce his authority may possibly be found in the constitution of the late confederate States. It is certainly not contained in that of the United States.

At the time of this correspondence the Union feeling in Louisiana was particularly jubilant, as will be seen by the following telegram to “The Right Way:”

“July 29. — The Commercial, in an extra, publishes the Governor’s proclamation ordering an election on the 3d of September to fill vacancies to the Constitutional Convention, There is great enthusiasm among Union men. The rebel Secretary of State refuses to affix his signature, but there is a decision of the Supreme Court which renders this unnecessary. Sheriffs, commissioners of elections, and other officers therein concerned are ordered to hold the elections. No one will be allowed to vote who has not taken the oath, as prescribed by the amnesty proclamation of the President of the United States, either of January 1, 1864, or May 29, 1865.

“An immense mass meeting is being held in this city to indorse the policy of Congress and the call for the reassembling of the convention of 1864. The greatest enthusiasm prevails. The State House is crowded, and also the street. Ex-Governor Hahn presides over the inside meeting and Judge Hasking over the outside. A torch-light procession, such as was never before seen in this city, will follow.”

THE MEMBERS OF THE CONVENTION ARE TO BE ARRESTED.

Meanwhile Judge Abell, of the second district, who had before made himself notorious by his disloyal decisions, and who had charged the grand jury with great violence against the convention, was preparing for the arrest of its members. There was apprehension, however, that the military force in the city would interfere for the protection of the convention, and a telegram on the 29th from New Orleans states:

“In an interview with the mayor yesterday, General Baird stated positively that he would prevent the sheriff and posse, or any State or civil officer, from interfering with the convention. The Tribune, a Republican paper, says the convention will meet to-morrow, and adjourn until the middle of September.” [After the election to supply vacancies.]

But there was a friend in power who could overrule the action of the military, and prevent their protecting an assembly of peaceable citizens. An application was consequently made to President Johnson, and the result is stated in the following telegraphic dispatch:

“New Orleans 29 th. — Yesterday the Attorney General of the State and the Lieutenant Governor telegraphed to the President of the United States, informing him of the violent incendiary proceedings and speeches at the Republican negro meeting the night before, stating that a serious riot was feared; that the Governor had issued a proclamation calling an election to fill vacancies in the bogus convention, and was in league with the Republicans; that it was intended to indict the members of the convention by the grand jury; and asking if the President, intended that the military forces of the United States should interfere to prevent the execution of civil process.”

The President replied as follows:

“Washington, July 28.

“To Albert Voorhies,

Lieutenant Governor of Louisiana:

“The military will be expected to sustain, and not obstruct or interfere with, the proceedings of the courts. A dispatch on the subject of this convention was sent to Gov. Wells this morning.

A. Johnson.”

A special to the New York Tribune from Washington, July 30, adds:

“A Col. Rozier, of New Orleans, telegraphed to the Attorney General of Louisiana to arrest every man engaged in setting up a new government. ‘We have seen the President, and he will do all that can be expected. Call upon the military for aid.’ These dispatches mean that the United States military are to be used to break 5 up the Union convention and old Mayor Monroe and his tribe of rioters.”

Of the dispatch to Washington the Transcript remarks:

“The above dispatch illy conceals the rage of prominent secessionists of New Orleans that Gov. Wells — who never was considered a Radical — should have called together the Constitutional Convention, probably for the purpose of ratifying the congressional amendment regarding representation and to make some necessary changes in the Constitution of the State. The convention is the same body which, under Gen. Banks, gave to Louisiana a constitution purged entirely of slavery. As to its legality, Gov. Wells was a far better judge than the rebel mayor of New Orleans, that, so late as the Fourth of July last, denied the axiom of the Declaration of Independence, that ‘all men are born free and equal.’ Its members were unquestionably entitled to the protection of the military forces of the United States; and the fact that it was not rendered emboldened the mob and permitted them, in connection with the local police, under the charge of a rebel mayor, to accomplish the work of breaking up the convention.”

THE CITY ON SUNDAY.

The excitement in the city on Sunday, the 29th, appears from the following telegram:

July 29. — The Constitutional Convention will meet to-morrow. There is great excitement in the city, and loud threats by the rebels sheriff, Gen. Harry Hayes, has sworn in a posse of deputies to promote this disruption. Members of the convention are openly threatened with the lamp-post; but the Union men are resolute and sanguine.”

Unfortunately the mayor of the city was John T. Monroe, whose political status is sufficiently fixed by the fact that he is the same rebel mayor of New Orleans who surrendered the city to the federal forces in 1862. The policy of the Administration in 1865 resurrendered the city to its old mayor, and gratitude as well as inclination called forth the following proclamation:

“Mayoralty of New Orleans, “City Hall, July 30, 1866.

“Whereas the Extinction Convention of 1864 proposes meeting this day; and whereas intelligence has reached me that the peace and good order of the city might be disturbed: Now, therefore, I, John T. Monroe, mayor of the city of New Orleans, do issue this my proclamation, calling upon the good people of this city to avoid with care all disturbances and collisions; and I do particularly call on the younger members of the community to act with such calmness and propriety as that the good name of the city may not be tarnished, and the enemies of the reconstruction policy of President Johnson be not afforded an opportunity, so much courted by them, of creating a breach of the peace and falsifying facts, to the great injury of the city and State; and I do further enjoin upon all good citizens to refrain from gathering in or about the place of meeting of said Extinction Convention, satisfied by recent dispatches from Washington that the deliberations of the members thereof will receive no countenance from the President, and that he will sustain the agents of the present civil government and vindicate its laws and acts to the satisfaction of the good people of the State.”

Subsequent events show that the object of this proclamation was to deprive the convention of the moral support of a large and respectable audience, and thus leave it more at the mercy of the intended mob. First among these events is the following correspondence with

MAJOR GENERAL BAIRD.

Mayoralty of New Orleans,

City Hall,

City Hall,

July 25, 1866.

Brevet Maj. Gen. Baird,

commanding, etc.:

General: A body of men claiming to be members of the convention of 1864, and whose avowed object is to subvert the municipal and State governments, will, I learn, assemble in the city Monday next.

The laws and ordinances of the city, which my oath of office makes obligatory upon me to see faithfully executed, declare all assembles calculated to disturb the public peace and tranquillity unlawful, and, as such, to be dispersed by the mayor, and the participants held responsible for violating the same.

It is my intention to disperse this unlawful assembly, if found within the corporate limits of the city, by arresting the members thereof and holding them accountable to existing municipal law, provided they meet without the sanction of the military authorities.

I will esteem it a favor, general, if, at your earliest convenience, you will inform me whether this projected meeting has your approbation, so that I may act accordingly.

I am, general, very respectfully,

John T. Monroe,

Mayor.

Headquarters

Department of Louisiana,

New Orleans,

July 26, 1866.

Hon. John T. Monroe,

Mayor of the city of New Orleans:

Sir:

I have received your communication of the 25th instant, informing me that a body of men, claiming to be members of the convention of 1864, whose avowed object is to subvert the present municipal and State governments, is about to assemble in this city, and regarding this assemblage as one of those described in the law as calculated to disturb the public peace and tranquility, and therefore unlawful, you believe it your duty, and that it is your intention, to disperse this unlawful assembly, if found within the corporate limits of the city, by arresting the members thereof and holding them accountable to the existing municipal laws, provided they meet without the sanction of the military authorities.

You also inquire whether this projected meeting has my approbation, so that you may act accordingly.

In reply, I have the honor to state that the assemblage to which you refer has not, so far as I am aware, the sanction or approbation of any military authority for its meetings.

I presume the gentlemen composing it have never asked for such authority to meet, as the military commanders, since I have been in the State, have held themselves strictly aloof from all interference with the political movements of the citizens of Louisiana. For my own part, I have carefully refrained from any expression of opinion upon either of the many questions relating to the reconstruction of the State government. When asked if I intended to furnish the convention a military guard, I replied — “No; the mayor of the city and his police will amply protect its sittings.” If these persons assemble, as you say is intended, it will be, I presume, in virtue of the universally conceded right of all citizens of the United States to meet peaceably and discuss freely questions concerning their civil governments, a right which is not restricted by the fact that the movement proposed might terminate in a change of existing institutions.

If the assemblage in question has the legal right to remodel the State government, it should be protected in so doing; if it has not, then its labors must be looked upon simply as a harmless pleasantry, to which no one ought to object. As to your conception of the duty imposed by your oath of office, I regret to differ with you entirely. I cannot understand how the mayor of a city can undertake to decide so important and delicate a question as the legal authority upon which a convention, claiming to represent the people of an entire State, bases its action.

This doubtless will, in due time, be properly decided upon by the legal branch of the United States Government. At all events, the Governor of the State would seem to be more directly called upon to take the initiative in a step of this kind if it was proper and necessary. What we most want at the present time is the maintenance of perfect good order and the suppression of violence. If, when you speak of the projected meeting as one calculated to disturb the public peace and tranquility, I am to understand that you regard the number of persons who differ in opinion from those who will constitute it as so large, and the lawlessness of their character as so well established, that you doubt the ability of your small force of police to control them, you have in such case only to call upon me, and I will bring to your assistance, not only the troops now present in the city, but, if necessary, the entire force which it may be in my power to assemble, either upon the land or on the water. Lawless violence must be suppressed, and in this connection the recent order of the lieutenant general, designed for the protection of citizens of the United States, deserves careful consideration. It imposes high obligations for military interference to protect those who, having violated no ordinance of the State, are engaged in peaceful avocations.

I am, sir, very respectfully, your obedient servant.

A. Baird,

Major General,

Commanding Department of Louisiana.

MEETING OF THE CONVENTION.

On the fifth day of July, the day fixed by the proclamation, the convention met. The following account of the transactions of that terrible day is taken from the New York Times, and is from its New Orleans correspondent. That paper is edited by Hon. Henry J. Raymond, under the supervision of Thurlow Weed, the godfathers of the President’s new party. Whatever bias the account contains may be set down as at least not in favor of the loyal men of Louisiana:

I have already forwarded a number of disconnected despatches relative to to-day’s fearful carnage, and now propose to give you a more connected account. I only write of what I saw with my own eyes, and which I can substantiate on the best authority.

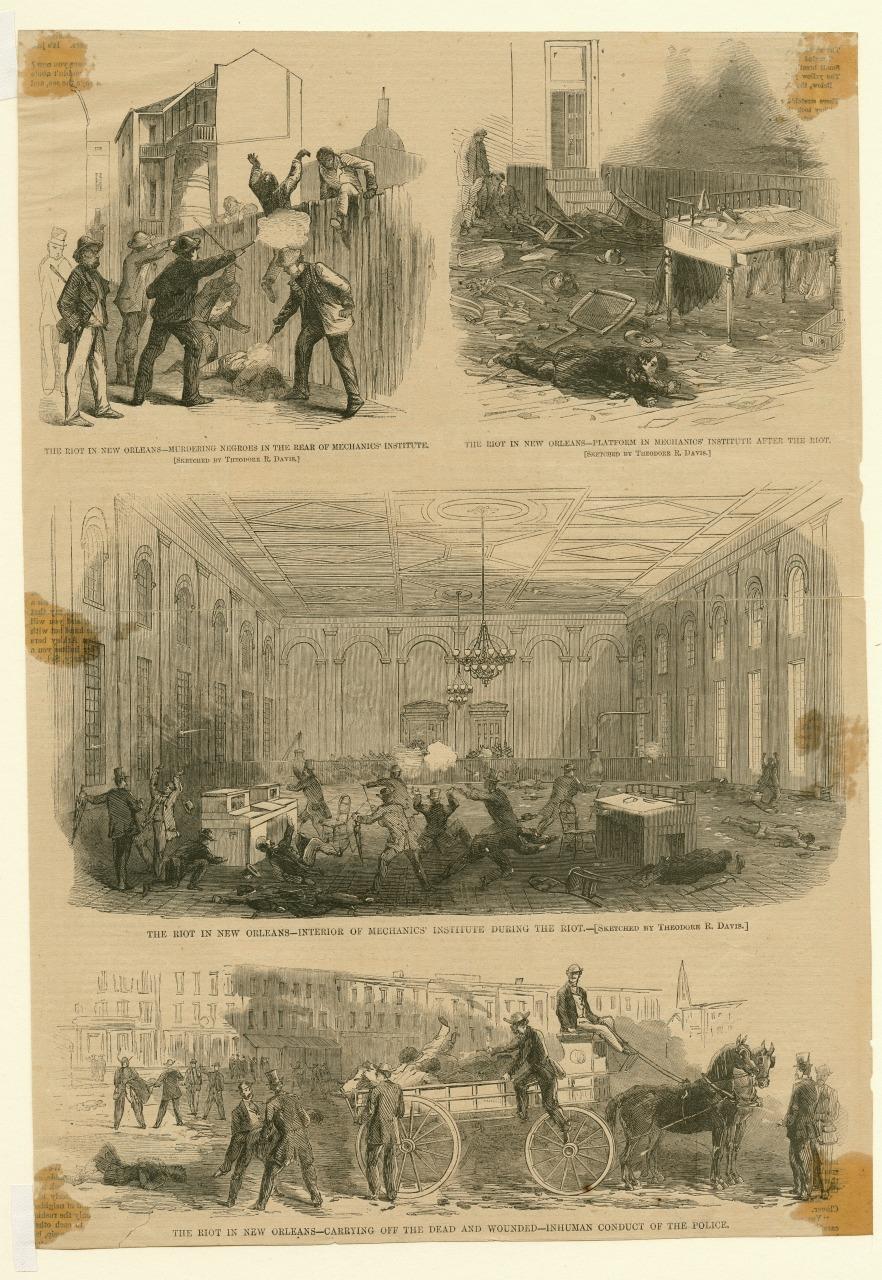

The convention met at 12 o’clock, 26 members being present, Judge R. K. Howell (since missing) in the chair. R. King Cutler (also missing) moved an adjournment of one hour, during which time the sergeant-at-arms was directed to compel the attendance of absentees. The hall was densely packed with freedmen and whites, the former having armed themselves extensively since their Friday’s demonstrations.

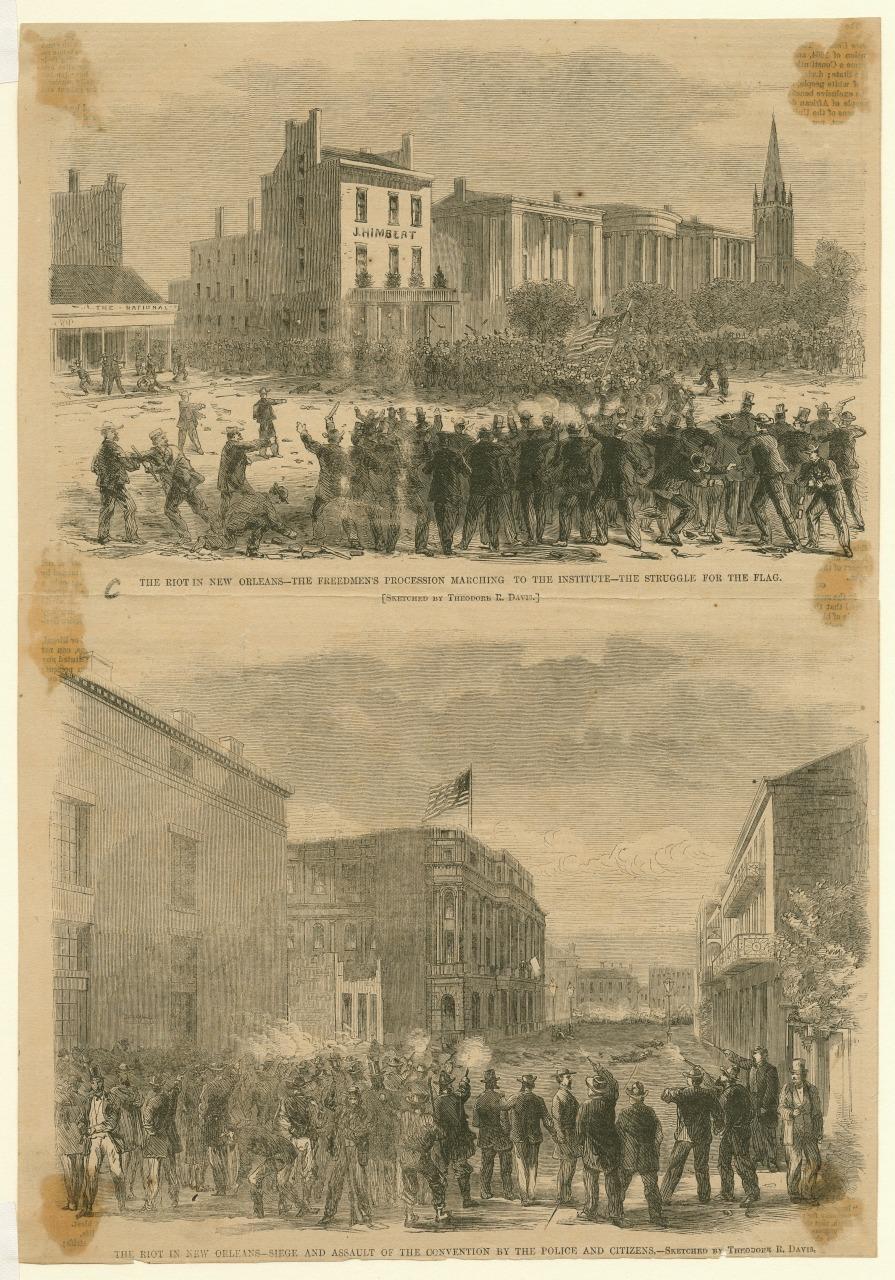

Just after the adjournment a procession, containing about a hundred freedmen carrying a United States flag, and marching through the streets with martial music, arrived at the Institute, having had a slight disturbance on Canal street. At this juncture the merchants all over the city, fearing the coming riot, closed their stores.

When the procession entered the building a squad of police followed, and attempted to make arrests. A scene of the wildest confusion followed. Pistols were fired, clubs and canes-used, and brick-bats flew in every direction. The policemen claim that they were merely attempting to arrest the Canal-street rioters above mentioned; but certain it is that they mounted the platform, where a small body of the members yet remained, and one of them presented a pistol at them, using offensive language. The policemen were finally driven out of the building, leaving inside Governor Hahn, Judge Howell, Mr. Dostie, and other gentlemen, mostly clerks attached to the State government, besides about fifty freedmen. Fortunately Governor Wells had just left the building for the purpose of consulting with General Baird about calling out troops, Sheridan being out of town.

The Institute, used now as the State capitol, is located on Dryades street, between Canal and Common, and when the policemen were driven out they were met by a large body of freedmen, who caused them to fall back to Canal street. Hiring a furniture cart, I used it as an observatory on Canal street, looking toward Common through Dryades. The policemen rullied, and drove the freedmen and their friends back to Common, who in turn were driven back to Canal, leaving Dryades perfectly clear of any vestige of humanity, except the bodies of three dead freedmen. Up to this time one police officer had been mortally wounded, one severely, and another slightly hurt with clubs and pistol shots. Police reinforcements soon appeared in Canal street, and the crowd of rioters accompanying the police. The police approached the Institute, and commenced throwing stones through the windows, and firing pistols at any one they could see inside the building. At the same time a detachment of police attacked the crowd of freedmen on Common street, and after sharp firing, and riddling and wounding several blacks, they drove them away.

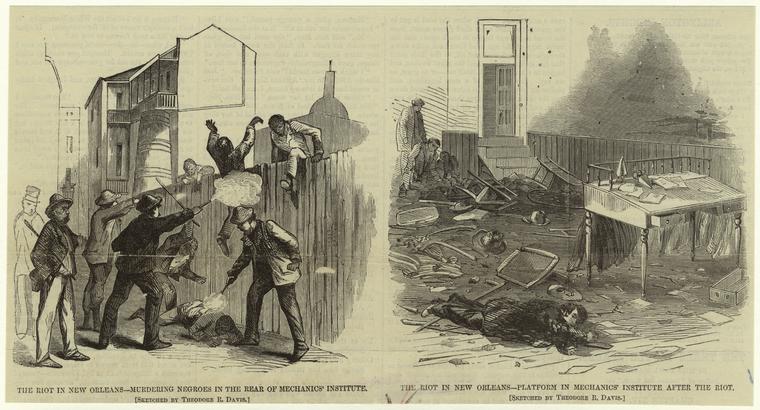

This gave the police and the mob which accompanied them full control of Dryades street. A fire engine was brought out and placed in front of the Institute; for what purpose I do not know. Several attempts were made by the police to enter the building, but they were repulsed. The ammunition of the men in the Institute seemed to give out about this time, as they did not fire any more. They attempted to escape through the rear of the Institute into Baronne street, but were met and either arrested or shot down. They also tried to escape through an alley which runs from Dryades to Baronne street on the Canal-street side. I do not know that any freedmen succeeded in getting away from the building alive, although I saw several at a distance from it being marched to the police headquarters. I think that every freedman who tried to escape from it was killed; and I saw several shot in the alley above mentioned, and after they fell I saw crowds of ruffians beating them as they were dying. The policemen, whatever their orders were, behaved well toward the white prisoners, comparatively speaking. A Mr. Fisk was the first conventionist captured; and I am happy to say, that although the police could not prevent the crowd from abusing him badly, they did keep him from being lynched. A man mounted a lamp-post on Canal street as Fisk was being carried by under guard, and got a rope ready to hang him; but the guard drove the crowd away with their pistols. The next member arrested was Captain Haynes, a Texas scout for our army during the war. The crowd had been taught a lesson, and did not interfere with him, although they grumbled deeply as he passed through, calling them “s—s of b—s,” “rebels,” “traitors,” and other pet names.

Governor Hahn succeeded in getting into the hands of the police unhurt from out of the building, where he had been, not as a member, but as one of the most prominent equal-rights men in the State. While he was under guard, however, some coward shot him through the back of the head, inflicting a dangerous wound, and he was also stabbed. He was then placed in a hack and carried to the police headquarters, where I saw him. He was very pale; blood trickled down his face from a wound which seemed to have reached his left temple.

Dr. Dostie, who has the reputation of being the most violent negro suffrage man in the South, and who certainly was the most violent speaker on Friday last, was killed while attempting to get away. I am told that a policeman shot him in the back, and that after he fell a crowd jumped on him and cut him horribly with knives.

John Henderson and other members of the convention were also captured, and were wounded by stray shots, the local papers say, but more likely by cowardly rioters while on their way to the station house.

The riot commenced at a quarter past twelve and ended at half-past three. At a quarter before three the military, under General Baird, appeared on Canal street, and finally took possession of the whole city.

Before night the riot was confined to Dryades, Baronne, Common, Carondelet, and Canal streets, and the building and yards all around the Institute. I saw freedmen shot down on all of the above streets, except Canal, who could have been arrested uninjured.

How many men have been killed, wounded, or even arrested, it is impossible to say; but my estimate is one hundred freedmen and twenty-five whites killed and wounded, and one hundred altogether arrested.

The substantial men of the city deplore the occurrence, but all are very violent in their expressions — some glorying in the murder of Dostie, and others in the murder of the freedmen.

“The Cincinnati Commercial,” a paper of the same political complexion, contains the following from its New Orleans correspondent, June 30:

“The mob, backed by the police, are reveling in blood; negroes and Union men are hunted down together.

“Since my last dispatch, I have traversed. Common and Dryades streets, past the capitol. The crowd on Common street was raging in the wildest manner; a negro was seen running, and immediately followed him with a hue and cry, shouting, ‘Kill him! shoot him!’ He disappeared in a yard behind the capitol. A drunken rowdy swung his revolver and yelled, ‘Hurrah for hell! hurrah for Louisiana!’ A stout citizen cried, with tears in his eyes and clenched fists, ‘It’s a shame! it’s a shame!’

“On Dryades street the mob had gathered about a trembling white man, saying, ‘Hold on there; we’ve got you now; say, were you in the army or not?’ A fire engine plunged into the street, driven by a drunken man, and shouts were heard, ‘Fire the Institute,’ that is, the capitol, where some of the convention were still at bay, defending their lives.

“Shots, like a skirmish fire, rang all about me. On Canal street I came upon blood on the pavement, and, being beckoned in, found Capt. Burke and also the chief of police wounded.

“A reign of terror broods. Respectable citizens are filled with chagrin and sorrow. The police have been, in every case to which I have been an eye-witness, the supporters and leaders of the mob. No marked Union man dared venture abroad.

“July 30, 7½ p.m. — The massacre is over for the present. It is now understood to have been a concerted plan on the part of the rebels, among whom the President’s dispatch was known yesterday morning. At the tap of a fire bell the rioters left their business, having lately purchased revolvers, to meet and be led by the police, who were also armed to the teeth. All rushed to the convention, breaking down the fences on Baronne street, in the rear of the capitol, which was surrounded by a force of police.

“They then ran into the building; and, while the crowd outside were firing into the windows, climbed the stairs inside, their leaders shouting, ‘Rally, boys — rally,’ and discharged their pistols into the Representative Hall, where there were, at the time, but fifteen conventioners (it being during the recess) within the railing, and about seventy-five negroes in the lobby, all of whom in the hall prostrated themselves to escape the shots. As soon as the pistols of the police were emptied, the besieged rose and drove out the assailants with chairs, at the same time barricading the doors. Then R. King Cutler called upon all those who had arms to leave the hall, and Captain Burke, the gallant chief of police deposed by Monroe, went out and fought his way back to Baronne street, escaping with a shot in the side.

“The fury of the besiegers increased, the barricade was broken, and pistols were again discharged. Then Rev. Mr. Horton, ex-army chaplain, who had made the prayer at the opening of the convention, advanced to the door, and, showing a white handkerchief, asked for himself and the rest to surrender. He was fired upon, hit by the shot in the forehead, then seized and beaten till he was insensible by the mob and police. One after another the members of the convention in the hall waved their handkerchiefs, protesting that they were unarmed and wished to surrender. Yet not a single arrest was made in the hall, but each man, as he came out, hoping to escape the certain fate threatened him if he remained, was seized and brutally handled by the police.

“Poor Dostie pleaded for his life. He was a Union exile; but, by his kind treatment to rebel families in the absence of their protectors, he had endeared himself to many even of his political enemies.”

The New Orleans Advocate, a loyal paper, of the date of August 4, gives the following account of the doings of the previous Monday:

In another column will be found a few statements in regard to the convention which was made the occasion and pretext for a slaughter of Union people, white and colored; and having been a witness to a portion of the riotous proceedings, we give below some facts in reference to the same.

Returning from the post office about half-past twelve o’clock on Monday last, in company with Rev. Mr. Jackson, who is one of the assistant editors of this paper, our curiosity led us to look in on the convention, to see what they were doing. We passed up Canal street until we arrived at Liberty street, on which the Mechanics’ Institute, the building occupied by the convention, is located; here was a gathering of people, mostly colored; we saw a band of music followed by a procession of colored people coming up Burgundy street toward us. We stopped near the corner to see the number in the procession, which appeared to be comparatively small, as it reached but little, if any, more than across Canal street. As the rear of the procession had come on to this street a pistol shot was heard near the southeast corner of Canal and Burgundy streets. The colored people scattered, thus breaking up the procession; none that we saw, however, running but a rod or two at the moment. One or two of these picked up loose cobble stones to defend themselves, thinking an attack was being made on them. The person firing the pistol went down Canal street, toward the river, and a number of colored people started in that direction. Thinking that a policeman had attempted to arrest some one at the rear of the procession, and through the individual’s refusing to go, or some other reason, he had fired his pistol, we ran among the colored people, some of whom appeared greatly excited, and told them to pay no attention to this affair, but go on to the meeting, and not let it be said to-day that they had any disturbance among them. Two or three instantly sanctioned my remarks, one saying, “yes, we are pledged not to have any disturbance on our part.” This was the substance, if not his exact words. We also remarked to several persons in different parts of the crowd, that if the police arrested any of their people, to make no attempt to rescue them, for they would only be taken to the station house at most, and if not guilty of any offense they would be discharged, but if they attempted to rescue them, it would create a disturbance. To this all seemed to acquiesce. They came on then toward the Mechanics’ Institute, but a half block distant. Soon there arrived a tall young colored man, who it seems was the person fired at. We went up to him and asked if he was hurt, and who shot at him. He replied that he was not hurt enough to amount to anything, that the ball only grazed his leg, at the same time pointing with his cane to his pants, which appeared to have received some injury. He replied that it was a white fellow that fired, and then ran; that he was not far distant when he fired; that he desired and endeavored to arrest him; that he struck at him with his cane, which he then had in his hand, but that he did not hit him, and that he had got away.

Supposing that the difficulty was all over, we went into the building. The convention, it seemed, had been opened by prayer by Rev. Mr. 9 Horton, but it appeared that there was not a quorum present, at least there was no business being attended to, but the people were in groups around the room, quietly engaged in conversation. As we were glancing about to see who were there, the firing of pistols commenced outside. Shots were fired in rapid succession. Many of the colored people who were nearest the doors rushed down stairs to see what was the matter; others ran to the side windows where they could get a partial view of the street, there being no front window on this floor from which they could see the street. We went to the head of the stairs, but they were so crowded that, instead of going down, we went up one flight of stairs higher, where we could look down from front windows into the street below. We could there see the policemen firing large revolvers rapidly into the small crowd of colored people around the door below. Other people were hurling bricks at them, and also hurling them at the windows of the room in which the convention was assembled. Occasionally we heard a shot fired from the door below, and saw two or three, perhaps more, bricks hurled towards the police. We saw one colored man lying dead on the opposite side-walk. One colored man only remained anywhere near on that side. Just as we looked out he, a man apparently well along in years, was walking moderately along, and had arrived within twenty or thirty feet of a police officer, when the latter leveled his revolver at him and fired. The poor man fell on his face, apparently dead. A citizen near the policeman, one of the ‘chivalry, ’ we suppose, not wishing to be out-done in fiendishness, threw a half brick at the head of the colored man after he fell on the pavement. As the police and the rest of the rioters were well armed, and as but very few of the colored people had come prepared for such an attack, of course the latter were quickly dispersed, though several by this time had been killed and wounded. We saw a federal officer, alone, exerting himself to the utmost to persuade the police and others to go away from the place. They retired half a block to Canal street, either because there were no more in front of the building to shoot at or to consult as to what they should do next. They were hooting and yelling every minute or two. There need have been no bloodshed after this, as now no one was molesting or opposing them. They were clearly the masters of the field. But no, their bloody programme was but just commenced. From our position we could see that they were rather beyond pistol range, and as the firing had all ceased, fearing that an attack might be made on the building, we concluded to leave. As we passed down they were just shutting and fastening the door leading into the room occupied by the convention. It was too late now to attempt to find our friend, from whom we had become separated when the firing commenced. We therefore passed on out of the building and walked rapidly in the opposite direction from the crowd towards Common street. We had gone but a few rods when they raised another yell, and, looking around, we saw they were rushing towards the building. As they were advancing we walked as rapidly as possible till, reaching Common street, we turned the corner and then ran up Common to Baronne. When near the latter street we knew by the yelling that a portion of the rioters were coming up that street also, and stepped into the office on the corner and let them pass by. They now had the building and even the square in which it was located surrounded. We then stepped out the front door on to Baronne street and hastened away from the vicinity. At the headquarters of General Baird we received information that orders had been sent for the colored regiment, in the upper part of the city, to report for duty, and soon learned that orders to the same effect had been sent to the white regiment at Jackson Barracks, below the city. There was considerable delay in their arrival, owing to the distance, and perhaps some other reasons, so that when they arrived the bloody work was about finished.

After the mob had surrounded the building, they fired at any one who appeared at the windows, or who endeavored to leave the building.

Our friend Rev. H. G. Jackson, who was within, and who was severely wounded, states to us that just before the first entrance of the police into the room, Dr. Dostie and R. K. Cutler, who were on the platform, called on the crowd to sit down and offer no resistance. They obeyed, and about twelve policemen then entered, ranged themselves in line, leveled their pistols, and commenced firing. The negroes immediately jumped up and fled affrighted to the platform. The police fired two or three volleys direct on the convention, when the members rallied, and by chairs and other means drove them back, but only when they found they were to be shot down after their surrender. We saw but few pistols used by members of the convention.

After three attempts the police effected a permanent entrance. Those within not being able to offer further resistance to the greatly increased force brought against them, could only surrender unconditionally. And such was their course.

They waved their white handkerchiefs, exclaiming, “We surrender, we surrender!” But like their infernal companions at Fort Pillow, and elsewhere in the late war, to anything but savage barbarity they were strangers.

They shot, clubbed, and stabbed indiscriminately. Some, among whom was Rev. Mr. Jackson, referred to above, were told by the policemen within to pass out. As soon as Mr. Jackson reached the stairs policemen and citizens assaulted him. He was immediately knocked down with clubs and then shot through the body. The ball entered the right side, and passing through both lungs, came out under the left arm. He is still living, and strong hopes are entertained of his recovery. But like all those who were wounded, and those who were not, he was taken to the police station and locked in a cell. His name was not recorded among the list of prisoners, and though we went to the 10 station house twice, we were informed that he was not there. And it was not until about nine o’clock at night that Dr. Avery, who had gained access to the cells, found him in his sad condition, and succeeded in obtaining his release. And to him too many thanks cannot be awarded. Rev. Mr. Horton, formerly of Boston, who was present and opened the convention with prayer, was shot through the arm, the ball entering his side and lodging, it is thought, in his lung. His head was horribly beaten and cut, and the skull fractured. There are two or three holes in his right cheek, but whether from pistol shots or not we have not heard. One of his fingers is also broken. He has been sensible only a short time since he was hurt, and it is not expected that he will live.

Mr. Fish, a young lawyer here, of an excellent mind and heart, informed us that he succeeded in reaching the sidewalk before getting knocked down. He hastened to a policeman near, and surrendering himself, desired to be taken prisoner that he might be protected. But the brute struck him on the head with a heavy revolver and knocked him down. He gathered up as quickly as possible, and hastened toward another police officer in the middle of the road to surrender himself and get protection, but this one, more villainous still, leveled his revolver at him. He turned and started to run toward Common street. But the policeman’s shot took effect in the back of his head, inflicting a horrible wound. He was also shot in the back and arm, and terribly beaten. One or two police, however, finally took charge of him and led him away. But we will not give each man’s account separately, as the military commission that has been ordered will collect their statements, and they will probably be published.

Among those seriously wounded of the whites, besides those mentioned above, are ex-Governor Hahn, Mr. Shaw, Mr. Henderson, Dr. Hire, Dr. Dostie, and many others. A lieutenant who was mustered out of the United States service a few days previous, and who was appointed by the convention sergeant-at-arms, was killed outright. Some of those mentioned above will probably die, as some of them have received so many and such severe wounds.

The colored people fared much worse. There were killed of these about forty or fifty, we judge, and probably nearly two hundred wounded — mostly shot. After General Baird had proclaimed martial law, on Monday evening, all those persons arrested in connection with the convention were released from the police station, and the wounded were sent to the Marine Hospital as rapidly as transportation could be furnished them. Some of them, however, were dead when they reached there. This number has since been increased to about one hundred and twenty-five. The Times says about thirty dead bodies lay in the street near the Mechanics’ Institute at one time, just as the riot had ceased. Some were killed in the house and at other places also.

The Bee of Thursday morning says that the bodies of 27 negroes killed in the riot were then lying at the city work-house awaiting the coroner’s inquest. How many wounded persons were taken by their friends to private houses is not known. So that the exact number of killed and wounded cannot be definitely ascertained. But we think the above a fair estimate.

The city papers published the next day after the riot claimed that twenty-two of the police had been hurt, one of whom died afterwards of his wounds. One of the citizens — a young man whom the papers laud, who was assisting the police — was killed.

We suppose that the above numbers include the special, i.e. firemen and citizens — all the rioters, as well as the special force.

The small number of the mayor’s party killed and the great slaughter on the other side shows plainly that those interested in the convention expected no difficulty, and were therefore not prepared for defense, while there is ample testimony, which will be produced, to show that the murderous attack on the convention had been previously planned.

The most horrible brutality was manifested in the boasting of some of the murderers, as well as in their actions. One man boasted of having killed three “niggers” with an axe. As one of those taken to the city hospital has had his skull cleaved open with an axe, and one side pried up, we suppose that this is one of this boaster’s victims. We suppose that the information that one of these still lives will lessen the enjoyment of the fiend, as perhaps he can now boast of having fully murdered only two.

One was heard to boast that six Yankee ministers had been killed by them. It may be a source of grief to them to know that there were only two, and those are not yet dead. The morning after the riot individuals were heard to make inquiry of their friends as to how many niggers they had killed the day previous.

We saw one young mulatto man, near headquarters, before the riot was over, who had escaped from the vicinity and who was crying with mingled sorrow and rage. He said that he was assisting a wounded colored man away, and a young boy came up and putting a pistol to the man’s breast fired it, and the man dropped from him dead. Many of those severely wounded were thrown into carts as carelessly as they would handle the dead bodies of swine. But we will not continue these horrid accounts further, though many of the most heart-rending cases we have not yet related, but will endeavor to do so in another issue.

It may be asked how so much destruction of life could take place before the soldiers were out to prevent it. But the military were probably not expecting trouble. The mayor, however, and his gang, it is thought, had fully agreed beforehand on the part they would perform, and it seems that the fire alarm was to be the signal that the war had commenced. The fire-bell rang, and the firemen and the rest of the “special police” were quickly on hand to participate.

Toward evening martial law was proclaimed by General Baird, and General Kautz was appointed military governor of the city. As the first regiment of regular infantry, the artillery, and the eighty-first colored infantry had been ordered out, and were parading the streets, there was perfect quiet throughout the city during the night. Had it not been for the military force, there is no knowing where the rioters would have ceased in their work. But their threats made on the streets since give us some indication.

At the time of our going to press martial law is still in force.

General Sheridan and staff returned from Texas on the day after the riot.

These accounts substantially agree. They show that the convention assembled for the purpose of deliberation; and, unarmed, was attacked and dispersed by a mob of the political friends of President Johnson, aided by the courts and the civil authorities of the city.

SHERIDAN’S DISPATCHERS.

The following correspondence will show the complicity of the Administration at Washington with the infamous doings of its friends in New Orleans, and the desperate effort of President Johnson to shield his ex-rebel partisans. Taken in connection with the foregoing letter of General Baird to Mayor Monroe, it will also show the extreme reluctance with which the military authorities refrained from protecting the loyal men of Louisiana against the positive order of the “Commander-in-Chief.”

The first of Sheridan’s dispatches was suppressed, and the second published in a mutilated form, by whom and for what reason can be best explained by Andrew Johnson.

It was only after the most imperative demands of Grant and Sheridan that all the dispatches were brought to light.

Office U. S. Military Telegraph,

Headquarters War Department.

The following telegram received 6 p.m., August 2, 1866:

U. S. Grant, General,

Washington, D. C.:

The more information I obtain of the affair of the 30th, in this city, the more revolting it becomes. It was not riot; it was an absolute massacre by the police, which was not excelled in murderous cruelty by that of Fort Pillow. It was a murder which the mayor and police of the city perpetrated without the shadow of a necessity. Furthermore, I believe it was premeditated, and every indication points to this. I recommend the removal of this bad man. I believe it would be hailed with the sincerest gratification by two-thirds of the population of the city. There has been a feeling of insecurity on the part of the people here, on account of this man, which is now so much increased, that the safety of life and property does not rest with the civil authorities, but with the military.

P. H. Sheridan,

Major General Commanding.

Washington, D. C.,

August 4, 1866.

To Major General Sheridan, Commanding, &c.,

New Orleans, La.:

We have been advised here that prior to the assembling of the illegal and extinct convention elected in 1864, inflammatory and insurrectionary speeches were made to a mob composed of white and colored persons, urging upon them to arm and equip themselves for the purpose of protecting and sustaining the convention in its illegal and unauthorized proceedings, intended and calculated to upturn and supersede the existing State government of Louisiana which had been recognized by the Government of the United States. Furthermore, did the mob assemble, and was it armed for the purpose of sustaining the convention in its usurpation and revolutionary proceedings? Have any arms been taken from persons since the 30th ult., who were supposed or known to be connected with this mob? Have not various individuals been assassinated and shot by persons connected with this mob, without good cause, and in violation of the public peace and good order? Was not the assembling of this convention and the gathering of the mob for its defense and protection the main cause of the riotous and unlawful proceedings of the civil authorities of New Orleans? Have steps been taken by the civil authorities to arrest and try any and all those who were engaged in this riot and those who have committed offenses in violation of law? Can ample justice be meted by the civil authorities to all offenders against the law? Will General Sheridan please furnish me a brief reply to the above inquiries, with other information as he may be in possession of? Please answer by telegraph at your earliest convenience.

Andrew Johnson,

President of the United States.

Office of U. S. Military Telegraph.

The following cipher telegram received 4.30 a. m., August 6, 1866, from New Orleans, Louisiana, August 6, 12 m., 1866:

His Excellency Andrew Johnson,

President of the United States:

I have the honor to make the following reply to your dispatch of August 4:

A very large number of the colored people marched in procession on Friday night, July 27, and were addressed from the steps of the City Hall, by Dr. Dostie, ex-Governor Hahn, and others. The speech of Dostie was intemperate in language and sentiments. The speeches of others, so far as I can learn, were characterized by moderation. I have not given you the words of Dostie’s speech, as the version published was denied, but from what I have learned of the man I believe they were intemperate.

The convention assembled at 12 m., on the 30th, the timid members absenting themselves because the tone of the general public was 12 omnious of trouble. I think there were about twenty-six members present. In front of the Mechanics’ Institute, where the meeting was held, there were assembled some colored men, probably 150.

Among those outside and inside there might have been a pistol in the possession of every tenth man. About 1 p.m. a procession of say from sixty to one hundred and thirty colored men marched up Burgundy street and across Canal street towards the convention, carrying an American flag. These men had about one pistol to every ten men, and canes and clubs in addition. While crossing Canal street a row occurred. There were many spectators on the streets, and their manner and tone towards the procession was unfriendly.

A shot was fired, by whom I am not able to state, but believe it to have been by a policeman at some colored man in the procession. This led to other shots and a rush after the procession. On arrival at the front of the Institute there was some throwing of brick-bats by both sides. The police, who had been held well in hand, were vigorously marched to the scene of the disorder. The procession entered the Institute with the flag, about six or eight remaining outside.

A row occurred between a policeman and one of the colored men, and a shot was fired by one of the parties, which led to an indiscriminate fire on the building through the windows by the policemen. This had been going on for a short time when a white flag was displayed from the windows of the Institute, whereupon the firing ceased and the policemen rushed into the building.

From the testimony of the wounded men and others who were inside the building, the policemen opened an indiscriminate fire upon the audience until they had emptied their revolvers, when they retired, and those inside barricaded the doors. The doors were broken in and the firing again commenced, when many of the colored and white people either escaped through the doors, or were passed out by the policemen inside.

But as they came out the policemen who formed the circle nearest the building fired upon them, and they were again fired upon by the citizens who formed the outer circle. Many of those wounded and taken prisoners, and others who were prisoners and not wounded, were fired upon by their captors and by the citizens. The wounded were stabbed while lying on the ground, and their heads beaten with brick-bats, in the yard of the building, whither some of the colored men escaped and partially secreted themselves. They were fired upon and killed or wounded by policemen.

Some men were killed and wounded several squares from the scene. Members of the convention were wounded by the policemen while in their hands as prisoners, some of them mortally. The immediate cause of this terrible affair was the assemblage of this convention. The remote cause was the bitter and antagonistic feeling which has been growing in this community since the advent of the present mayor, who in the organization of his police force selected many desperate men and some of them known murderers.

People of New Orleans were overawed by want of confidence in the mayor and the fear of the thugs, many of whom he had selected for his police force. I have frequently been spoken to by prominent citizens on this subject, and have heard them express fear and want of confidence in Mayor Monroe, ever since the intimation of this last convention movement. I must condemn the course of several of the city papers for supporting by their bitter articles the bitter feeling of bad men.

As to the merciless manner in which the convention was broken up, I feel obliged to confess strong repugnance. It is useless to attempt to disguise the hostility that exists on the part of a great many here toward northern men; and this unfortunate affair has so precipitated matters that there is now a test of what shall be a status of northern men; whether they can live here without being in constant dread, or whether they can be protected in life and property and have justice in the courts. If this matter is permitted to pass over without a thorough and determined prosecution of those engaged in it, we may look out for frequent scenes of the same kind.

No steps have as yet been taken by the civil authorities to arrest citizens who were engaged in this massacre, or policemen who perpetrated such cruelties. The members of the convention have been indicated by the grand jury, and many of them arrested and held to bail. As to whether the civil authorities can mete out ample justice to the guilty parties on both sides, I must say it is my opinion unequivocally that they cannot.

Judge Abell, whose course I have watched for nearly a year, I now consider one of the most dangerous that we have here to the peace and quiet of the city. The leading men of the convention, King Cutler, Hahn, and others, have been political agitators and are bad men. I regret to say that the course of Governor Wells has been vaciliating, and that during the late trouble he has shown very little of the man.

P. H. Sheridan,

Major General Commanding.

ADDRESS OF GOVERNOR WELLS.

Foiled by executive interference in his attempt to bring his State into the Union as a loyal State, Governor Wells issued the following address.

TO THE LOYAL PEOPLE OF LOUISIANA.

The bloody tragedy enacted in the city of New Orleans on the 30th day of July, 1866, in which more than three hundred citizens were killed or wounded, has, to the credit of humanity, created a profound sympathy in the breast of every man throughout the length and breadth of this country. The remote and immediate causes of this outrage demand a thorough investigation and explanation, and, as the Chief Magistrate of the State, I feel a solemn duty resting upon me to give a plain and unvarnished statement of its origin and progress. In doing this, it becomes necessary for me to commence in the year 1864, at the re-organization of civil government in that portion of Louisiana which had been wrested from rebel authority. I regret that I shall, in this 13 connection, be obliged to speak of myself. It is not to gratify any feeling of vanity that I do so; for I fully realize that I am but an insignificant man in the great cause of maintaining and perpetuating the union of these States. The political history of the country teaches us that, under the policy of the late lamented President, all the loyal citizens of Louisiana, in parishes then within the Union lines, were invited and authorized, in the proclamation issued by the military commander of this department, to hold an election on the 22d day of February, 1864, for State officers. The election was held; and then, being a refugee from my parish in the rebel lines, in consequence of my Union sentiments, I was nominated by the Free State Party, as it was called, and also by the extreme Radical party, of which Thomas J. Durant was the acknowledged leader, as their candidate for the office of Lieutenant Governor. The first named ticket, headed by Michael Hahn for Governor, was elected. Governor Hahn served until the 4th of March, 1865, when, by his resignation, I succeeded to the office of Governor. In the meantime, and by virtue of military authority, an election for delegates to a State convention to amend and revise the constitution of 1852 had taken place, the convention had met, framed a constitution, declaring slavery to be abolished, which constitution is now the fundamental law of the State. It is further well known that the convention did not adjourn “sine die,” but subject to the call of the President “for any cause.” A Legislature had also been elected and was in session at the time of the assumption by me of the duties of the office of Governor

Shortly afterwards, the collapse of the so-called Confederate Government took place; and, by the surrender of the forces in the trans-Mississippi Department, the entire territory of the State was restored to the lawful authority of the United States. When this event took place, what was my conduct towards the population of the twenty-eight parishes reclaimed? Although I had been persecuted and driven from my home by the rebel authorities, I suppressed all feeling of rancor so natural to the human breast under the circumstances, in the belief that a majority had been seduced from their allegiance to the old flag by the wiles of the artful demagogues who brought on the rebellion. I determined to try the effect of kindness and conciliation in weaning them back to their first love. I addressed them a proclamation, congratulating them on their restoration to the protection of a Government of law and order; and that, as far as I was concerned, I was willing to forget the past. I begged them to submit cheerfully and unreservedly to the new order of things, and assured them that, although a State Government had been organized, yet I was anxious that a general election for State officers should be held, in which the whole State could participate. I fulfilled every word of my promises. I appointed men recommended by them to fill the offices in the several parishes; I signed their applications to the President of the United Stated for special pardon; I persisted in my course of reconciliation, notwithstanding the warnings and remonstrances of Union men, who believed that my policy would be unavailing in accomplishing the purpose intended, and who predicted that at the very first election, these men, in every parish where they held the power, would prescribe every man from office who had not been in the rebel army and fought for the rebel cause.

These predictions have been realized to the letter at every subsequent election, with the exception of my own case; and it is well known, for it was publicly avowed, that I was put at the head of their ticket simply because it was thought I could be useful in securing a representation of the State in Congress. It is further well known that the platform reported by the committee appointed for that purpose to the Democratic Convention held in this city, was a reiteration of the doctrine of the right of secession; and it was only through the exertions of a few of the more cautious and politic of the party that this platform was made to assume the form in which it was adopted. At the same convention, a well-known citizen and life-long democrat was publicly censured by resolution, because in a speech, delivered before that body, he said that “secession was worse than a crime: it was a blunder.”

Notwithstanding my nomination by the Democratic party, another candidate was put in the field in opposition to me, who had officiated as Governor under rebel rule, and who, had he been in the country, and signified his assent, I have no doubt would have been overwhelmingly elected.

When the members of the Legislature met in extra session in the month of November, 1865, convened by me for the purpose of raising money to restore the broken levees and to take measures to redeem the credit of the State, I found they were more intent on calling a convention to change the constitution of 1864, than to promote the material interests of the people. Their chief objection to that instrument was the character of the men who framed it and the abolition thereby of slavery. Having failed at the extra session to pass a bill calling a convention, the attempt was renowed at the regular session, held in the month of January, and more than half the time of that body was spent in discussing that question. Finally, a committee was sent to Washington to consult the President; and the Legislature only abandoned the measure through his advice.

I considered a convention inexpedient, and for that reason opposed it. I had learned enough of the real sentiments of the people to convince me, that if a new constitution was made, it would be less in harmony with the views of the President and Congress than the constitution of 1864, the result of which would be to lessen the chances for the admission of our representatives. I urged these views on the members of both Houses of the Legislature, but they had no effect with the majority.

I deprecated the city and parochial elections for the same reason. I feared the result, because of the character of the men that would be elected; because I had seen enough of public sentiment to convince me that none but those who had served in the Confederate army, or who had gone into the Confederate lines would be elected to office. I foresaw that such a result would be justly regarded by the people 14 of the loyal States as showing a defiant spirit, and as still glorying in a cause that had been crushed by them with such fearful loss of life and expenditure of treasure.

With numerous and repeated evidences of the continuance of an intolerant and rebellious spirit and the manifestation of the proscription of all who did not adhere to the fortunes of the Confederacy to the last, on the part of a large majority of the citizens; and with a press almost unanimously expressing sentiments of the same tenor, is it a matter of surprise that I should pause and commence to reflect on the consequences, both as regards the future security of the Government and the fate of Union men in the South, if these men, who once attempted to break up the Union, succeeded in grasping the power of the nation again. I had seen that, while professing with their lips renewed allegiance to the flag and oblivion of the past, emboldened by the pacific policy of the President, they were becoming arrogant, intolerant and dictatorial. They glory in the apparent schism between the President and Congress in the policy of restoring the States lately in rebellion, and rub their hands with delight at the idea of a civil war in the loyal States.

In view of all this array of strong, stubborn facts, I frankly own that my views of the conciliatory policy, in winning back to allegiance those who have been engaged in a war to destroy the Union, have undergone a change. The intolerant spirit engendered by slavery still exists; the loss of property and failure of all their hopes can never be forgiven, and though I regard them as impotent to resist the constituted authorities, enforced by the presence of the military, yet I am convinced they would renew the rebellion to-morrow if they saw a prospect of success.

Impressed with the truth of these views, foreseeing the necessity for the future security of the Union, and the safety of the lives of Union men in the South, that the amendment to the Constitution adopted by Congress, and submitted to the several States for ratification should prevail; and fully realizing the fact that the amendment would never be ratified by the present Legislature, I own I was in favor of the reassembling of the convention of 1864, as the only means of securing ratification as required, and thereby insure the admission of our representatives in Congress.

The legal right of that convention to continue its functions is a question, I suppose, properly pertaining to the courts to decide. Senators and Representatives in Congress, of great learning, and men of high legal attainments in New Orleans, have expressed the opinion that under the resolution of adjournment the convention could lawfully reassemble. A distinguished Democratic Senator in Congress took the same view. For myself, if I had any doubt on the subject, which I have not, I should have deferred to the opinion of abler men.

The total number of delegates composing the convention was one hundred and fifty; the number elected ninety-three. The quorum was fixed at seventy-six, this number being a majority of the whole. There were twenty-seven parishes unrepresented in the convention, entitled to fifty-one delegates, and, adding thereto ten vacancies to be filled, would make sixty-one delegates to be elected.

Besides, there were some ten or twelve delegates who, disapproving the emancipation clause, refused to sign the constitution, and who may be ranked with the extreme conservatives. Counting the sixty-one delegates to be elected to be of the same class, and the balance of the convention to be radical, it will be seen that parties would have been nearly equally divided. I have gone into these details to show the falsity of the charges that have been made, that the convention would not have represented the whole people and that it was intended to be packed. Every parish would have been represented; about one-half, having elected their delegates in 1864, and the other half in 1866, making a just equilibrium between those who opposed and those who sustained the cause of the Confederacy.

There are no disenfranchising clauses in the constitution of 1864. The much abused members of that body had it in their power to have made a constitution as stringent against those engaged in the rebellion as Tennessee and Missouri have done. They pursued an opposite course, believing and trusting, as I did, that these men would be actuated by a spirit of tolerance and forbearance, in return for the liberality shown towards them. How the members of that convention have been treated individually by the very men in whose honor and good faith they trusted, to say nothing of the scorn and vilification fulminated against them as a collective body, and the constitution they made, let the record of the bloody doings at the Mechanics’ Institute on Monday, the 30th ult., answer.

In keeping with their unrelenting policy to maintain the power of the State in their own hands exclusively, they opposed the meeting of the convention of 1864. They needed no better monitor than their own conscience, to tell them that by their proscriptive conduct they had forfeited all claim to further liberality from the original members of that convention. They resolved it must be put down, crushed out, at all risk, and the terrible scenes of the 30th of July, confidently predicted in case the convention met, was the result.

The letter of Mayor Monroe to General Baird, accompanying this communication, is convincing proof that it was the determination, if every other means failed, to resort to force. Everything was arranged on Sunday preparatory to that purpose. The police received their orders, and on Monday morning they were in large numbers at the corner of Canal and Dryades streets, each having one or more revolvers on his person. Why were they there except to commit violence? Admitting all that has been charged against the speakers at the Friday night meeting, they counseled nothing more than the blacks should come armed to defend the convention in case the members were attacked. Admitting they had assembled there for that purpose, what occasion was there for alarm, unless it was meditated to assault the convention? The inference is irresistible, from the massing of the police alone, that it was designed to break up the convention by force. For this purpose a beginning was 15 necessary and opportunity sought for. This soon occurred by the arrival of a procession of blacks, with music, on their way to the place of meeting of the convention, which procession had to enter the street through the crowd of policemen and citizens at the corner of Canal, and were met with insults and jeers, which brought on a collision; a shot was fired, but ended in nothing serious. The next act of violence was the arrest of a colored man by a policeman, in the front of the Institute, but for what offense I am unable to say. The crowd of colored persons assembled naturally became excited at this occurrence, the same as a body of white men would do under the same circumstances; some took the side of the policemen, others the side of the prisoner; brick- bats were thrown and a shot fired, the testimony going to show it was done by one of the colored crowd. It was answered immediately by several shots from the crowd of policemen at the corner, and followed up by rapid firing on the crowd of blacks, who returned the fire as best they could; but being overpowered and driven from the street, they took shelter in the Mechanics’ Institute.

If the object of the police was simply to preserve the peace, why did they not, after the men had taken refuge in the Institute, retire to their original positions at the corners of the streets, which effectually cut off egress from the front, and placing a guard to watch the rear of the building, await the arrival of the military, who were known to be on their way. The only reason for their course is: it did not suit their purposes. They accordingly advanced in front of the building, and besieged it on all sides. Every negro who attempted to escape was murdered. The crowning climax of these bloody acts are well known. When the white flag was hung out, as a token of surrender, the police entered, arrested the members of the convention and other white citizens, brought them into the streets, where the most prominent for their Union sentiments were shot, stabbed, and beaten in the custody and presence of the entire police force of the city. Why did not the mayor or his chief station a guard at the door even then, forbid any person from entering, and await the arrival of the military.

By this means, the last, most deliberate, and horrible phase of this bloody tragedy would have been avoided. It is also notorious that the police failed to arrest, or to attempt to arrest, even one of the riotous citizens, who, according to their oft-repeated statements, were continually attacking, wounding and killing prisoners who had surrendered to them and were in their custody.

I think I have fully shown it was the design of those opposed to the convention to break it up by force. The inference to be drawn from the letter of the mayor is that such a course was resolved on, and the massing of the police, and their willingness to rush into the fight, I think fully establishes the fact.

The causes of this exhibition of violence and mob law must be traced further back. It is the embers of the fires of the rebellious feeling which plunged this country into a desolating civil war, and which flame is not yet extinguished in the breasts of the former slave-holding aristocracy. Foiled in their first attempt to destroy the Government, they seek to regain political power by the same spirit of violence by which the leaders and chiefs have maintained their supremacy over the people before the war.

My deliberate conviction is, that if the military forces be withdrawn, the lives of Union men who proved themselves conspicuous in maintaining their allegiance will not be safe.

The ultimate security, both of the Government and the Union men of the South, depends, in my opinion, on the ratification of the constitutional amendment proposed by Congress, and the enfranchisement of the loyal black man as he may become educated and qualified to exercise that important privilege.

If the advocacy of these measures identifies me with the Radical party, as it is called, and in opposition to the policy of the President, I must accept the situation, because I cannot change my conviction in respect to principles and measures I deem necessary to preserve and perpetuate the Union.

J. Madison Wells,

Governor of Louisiana.

Not content with having dispersed the convention by riot and bloodshed, the party in power next proceeded to indict the members for the crime of peaceably assembling to deliberate. On August 3, Judge Abell, a thorough adherent of the President’s new policy, charged the grand jury that the members of the convention had themselves been guilty of a riot in attempting, as he styles it, to subvert the government of the State. Under this charge the grand jury found a true bill, charging the members with the singular and anomalous crime of “unlawfully claiming themselves to be and constitute a convention for the revision and amendment of the Constitution of Louisiana.”

SERIOUS REFLECTION.

This bloody tragedy, in which the President of the United States is too prominent an actor, gives rise to serious reflections. Is despotic power so dear to the Commander-in-Chief of the forces of the nation that, having once tasted it during war from the necessity of the case, he cannot resign it when peace is restored? That was the weakness of Cromwell; that was the weakness of Napoleon. That is why England and France are not now republics.

Grant that the convention was not a duly authorized constitutional convention of the State of Louisiana, by what provision of the Constitution and laws of the United States was the President authorized to inquire into or decide its legality? Who conferred upon him the power to disperse it? Has he forgotten that the Government of the country is one of limited power, and that one of the things it cannot do is to prevent the peaceable assembling of any citizens on any pretext in time of peace? Has he forgotten that the Executive of a government of limited powers cannot have greater power than his government?

For the man who thus tampers with the liberties of the people a fearful day of reckoning is at hand. Andrew Johnson is not Napoleon; he is not Cromwell. Let him take warning by his more fitting, prototype, John Tyler.

Text prepared by:

- Bruce R. Magee

- Broady Rivet

- Hannah Robinson

- Erika Roycroft

Source

Wells, Governor J. Madison, President Andrew Johnson, R. K. Howell, et al. The New Orleans Riot: “My Policy” in Louisiana. Compiled from Dispatches, Proclamations, Letters, &c. Washington, D.C.: Daily Morning Chronicle Print. 1866. <http:// www.loc.gov/ resource/ rbaapc. 20600>.