Reuben Gold Thwaites.

“Daniel Boone.”

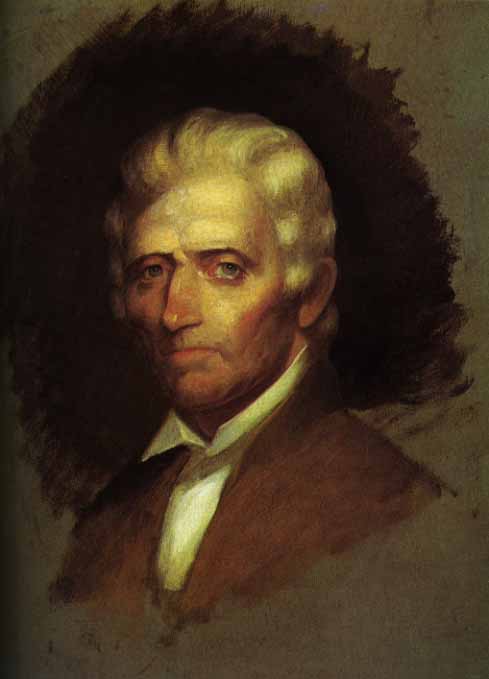

From the portrait by Chester Harding made in 1819, when Boone was eighty-five years old.

PREFACE

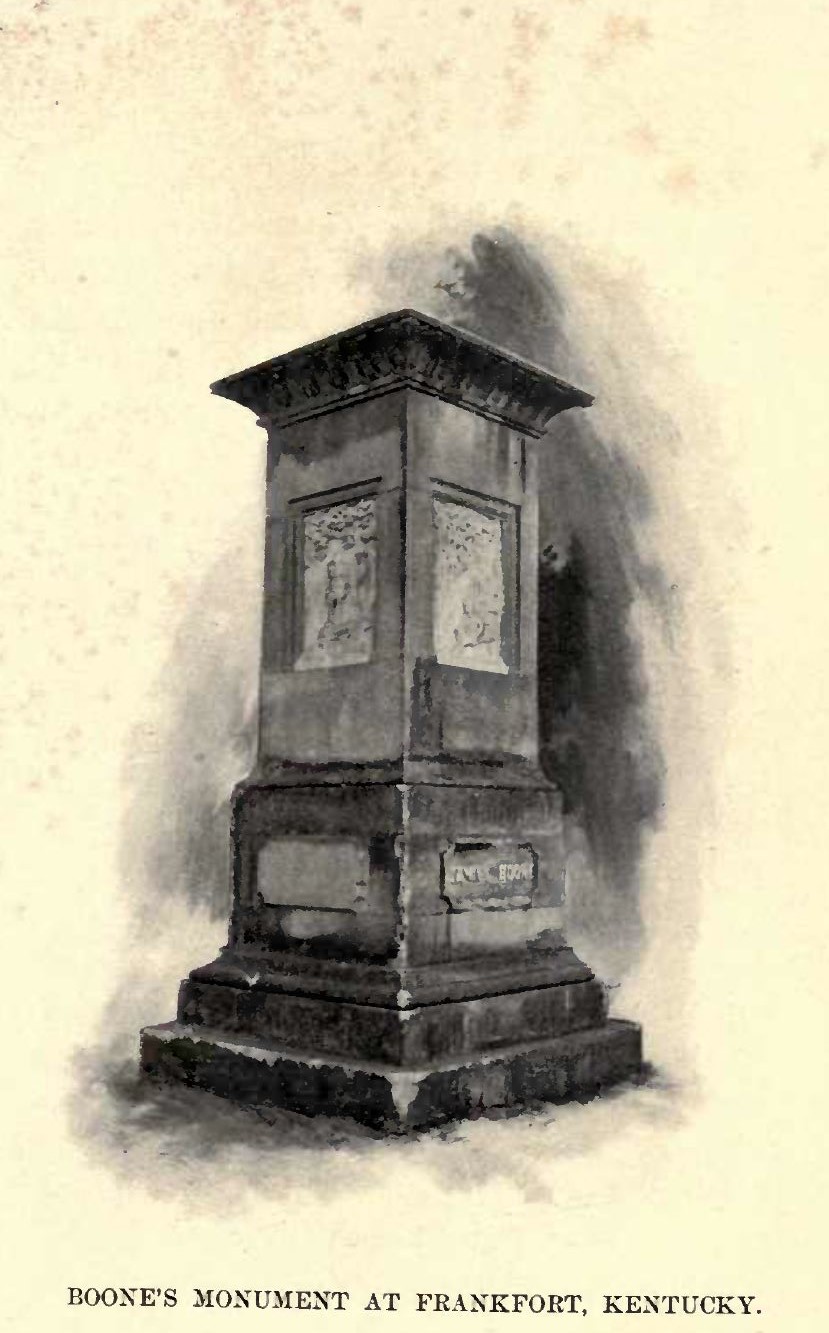

Poets, historians, and orators have for a hundred years sung the praises of Daniel Boone as the typical backwoodsman of the trans-Alleghany region. Despite popular belief, he was not really the founder of Kentucky. Other explorers and hunters had been there long before him; he himself was piloted through Cumberland Gap by John Finley; and his was not even the first permanent settlement in Kentucky, for Harrodsburg preceded it by nearly a year; his services in defense of the West, during nearly a half century of border warfare, were not comparable to those of George Rogers Clark or Benjamin Logan; as a commonwealth builder he was surpassed by several. Nevertheless, Boone's picturesque career possesses a romantic and even pathetic interest that can never fail to charm the student of history. He was great as a hunter, explorer, surveyor, and land-pilot — probably he found few equals as a rifleman; no man on the border knew Indians more thoroughly or fought them more skilfully than he; his life was filled to the brim with perilous adventures. He was not a man of affairs, he did not understand the art of money-getting, and he lost his lands because, although a surveyor, he was careless of legal forms of entry. He fled before the advance of the civilization which he had ushered in: from Pennsylvania, wandering with his parents to North Carolina in search of broader lands; thence into Kentucky because the Carolina borders were crowded; then to the Kanawha Valley, for the reason that Kentucky was being settled too fast to suit his fancy; lastly to far-off Missouri, in order, as he said, to get “elbow room.” Experiences similar to his have made misanthropes of many another man — like Clark, for instance; but the temperament of this honest, silent, nature-loving man only mellowed with age; his closing years were radiant with the sunshine of serene content and the dimly appreciated consciousness of world-wide fame; and he died full of years, in heart a simple hunter to the last — although he had also served with credit as magistrate, soldier, and legislator. At his death the Constitutional Convention of Missouri went into mourning for twenty days, and the State of Kentucky claimed his bones, and has erected over them a suitable monument.

There have been published many lives of Boone, but none of them in recent years. Had the late Dr. Lyman Copeland Draper, of Wisconsin, ever written the huge biography for which he gathered materials throughout a lifetime of laborious collection, those volumes — there were to be several — would doubtless have uttered the last possible word concerning the famous Kentucky pioneer. Draper’s manuscript, however, never advanced beyond a few chapters; but the raw materials which he gathered for this work, and for many others of like character, are now in the library of the Wisconsin State Historical Society, available to all scholars. From this almost inexhaustible treasure-house the present writer has obtained the bulk of his information, and has had the advantage of being able to consult numerous critical notes made by his dear and learned friend. A book so small as this, concerning a character every phase of whose career was replete with thrilling incident, would doubtless not have won the approbation of Dr. Draper, whose unaccomplished biographical plans were all drawn upon a large scale; but we are living in a busy age, and life is brief — condensation is the necessary order of the day. It will always be a source of regret that Draper’s projected literary monument to Boone was not completed for the press, although its bulk would have been forbidding to any but specialists, who would have sought its pages as a cyclopedia of Western border history.

Through the courtesy both of Colonel Reuben T. Durrett, of Louisville, President of the Filson Club, and of Mrs. Ranck, we are permitted to include among our illustrations reproductions of some of the plates in the late George W. Ranck’s stately monograph upon Boonesborough. Aid in tracing original portraits of Boone has been received from Mrs. Jennie C. Morton and General Fayette Hewitt, of Frankfort; Miss Marjory Dawson and Mr. W. G. Lackey, of St. Louis; Mr. William H. King, of Winnetka, Ill.; and Mr. J. Marx Etting, of Philadelphia.

R. G. T.

Madison, Wis., 1902.

CONTENTS

- Preface i

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| FACING PAGE | |

| Portrait of Daniel Boone | Frontispiece |

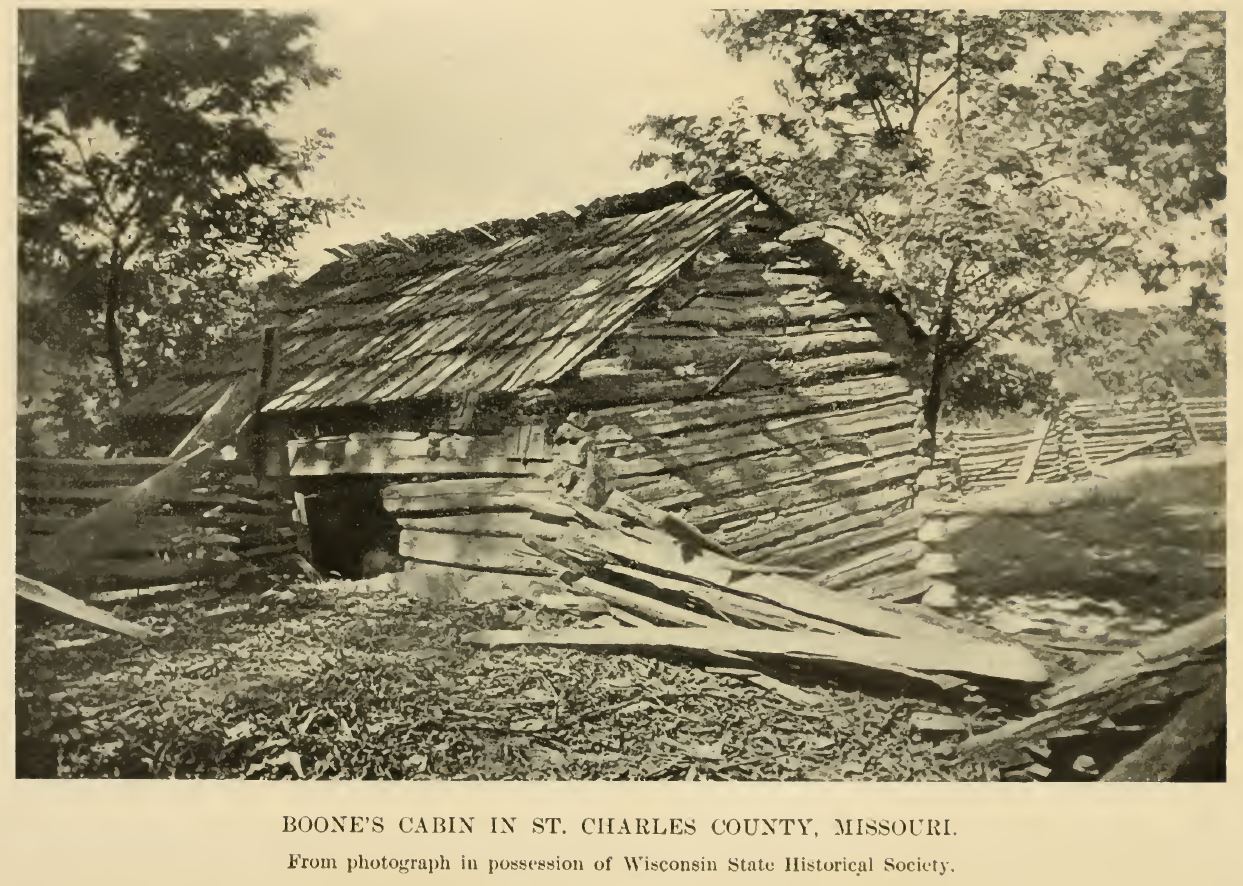

| Boone’s cabin in St. Charles County, Missouri | 224 |

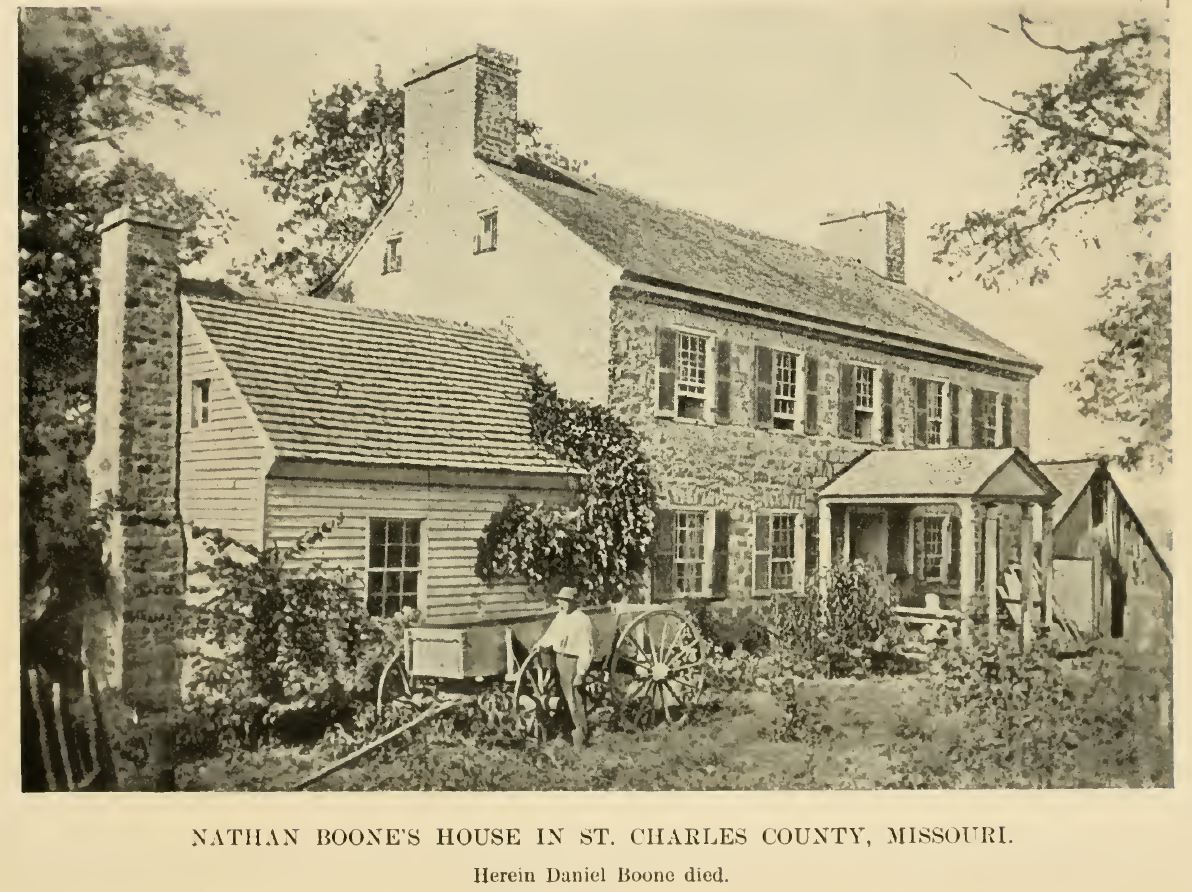

| Nathan Boone’s house in St. Charles County, Missouri | 230 |

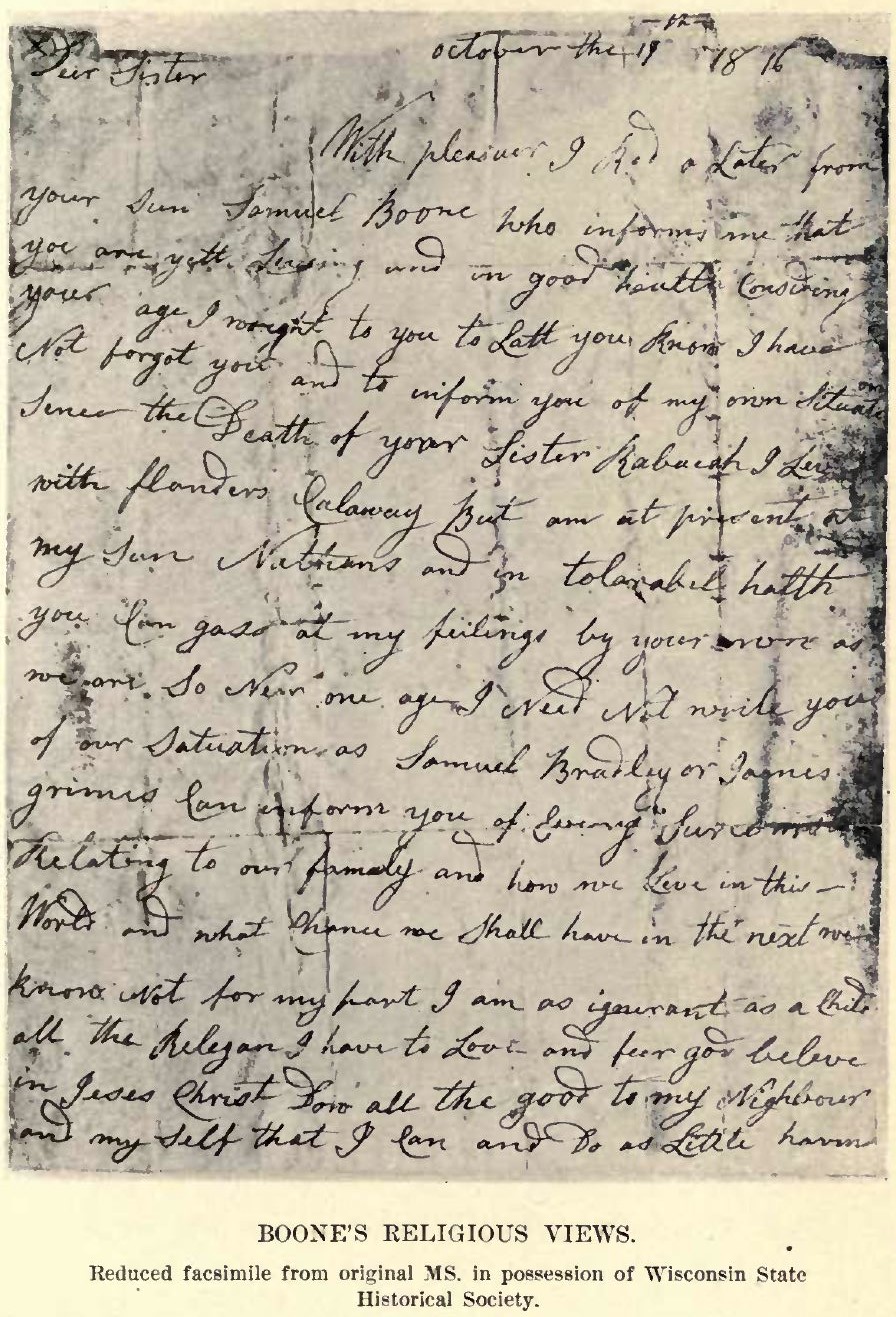

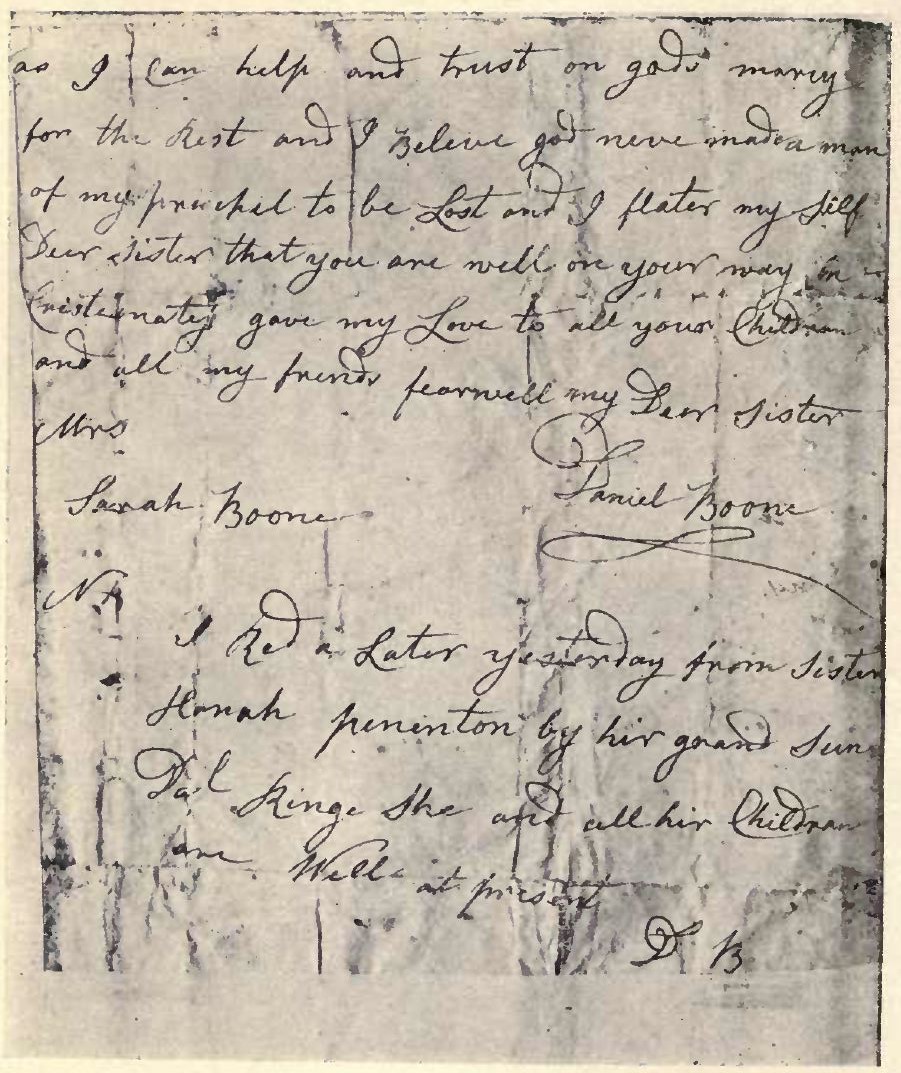

| Boone’s religious views (two pages) | 234 |

| Boone’s monument at Frankfort, Ky. | 240 |

DANIEL BOONE

CHAPTER XIV

IN THE KANAWHA VALLEY

During his early years on the Kanawha, Boone kept a small store at Point Pleasant. Later, he moved to the neighborhood of Charleston, where he was engaged in the usual variety of occupations — piloting immigrants; as deputy surveyor of Kanawha County, surveying lands for settlers and speculators; taking small contracts for victualing the militia, who were frequently called out to protect the country from Indian forays; and in hunting. Some of his expeditions took him to the north of the Ohio, where he had several narrow escapes from capture and death at the hands of the enemy, and even into his old haunts on the Big Sandy, the Licking, and the Kentucky.

He traveled much, for a frontiersman. In 1788 he went with his wife and their son Nathan by horseback to the old Pennsylvania home in Berks County, where they spent a month with kinsfolk and friends. We find him in Maysville, on a business trip, during the year; indeed, there are evidences of numerous subsequent visits to that port. In May of the following year he was on the Monongahela River with a drove of horses for sale, Brownsville then being an important market for ginseng, horses, and cattle; and in the succeeding July he writes to a client, for whom he had done some surveying, that he would be in Philadelphia during the coming winter.

In October, 1789, there came to him, as the result of a popular petition, the appointment of lieutenant-colonel of Kanawha County — the first military organization in the valley; and in other ways he was treated with marked distinction by the primitive border folk of the valley, both because of his brilliant career in Kentucky and the fact that he was a surveyor and could write letters. One who knew him intimately at this time has left a pleasing description of the man, which will assist us in picturing him as he appeared to his new neighbors: “His large head, full chest, square shoulders, and stout form are still impressed upon my mind. He was (I think) about five feet ten inches in height, and his weight say 175. He was solid in mind as well as in body, never frivolous, thoughtless, or agitated; but was always quiet, meditative, and impressive, unpretentious, kind, and friendly in his manner. He came very much up to the idea we have of the old Grecian philosophers — particularly Diogenes.”

By the summer of 1790, Indian raids again became almost unbearable. Fresh robberies and murders were daily reported in Kentucky, and along the Ohio and the Wabash. The expedition of Major J. F. Hamtramck, of the Federal Army, against the tribesmen on the Wabash, resulted in the burning of a few villages and the destruction of much corn; but Colonel Josiah Harmar’s expedition in October against the towns on the Scioto and the St. Joseph, at the head of nearly 1,500 men, ended in failure and a crushing defeat, although the Indian losses were so great that the army was allowed to return to Cincinnati unmolested. Boone does not appear to have taken part in these operations, his militiamen probably being needed for home protection.

The following year the General Government for the first time took the field against the Indians in earnest. For seven years it had attempted to bring the tribesmen to terms by means of treaties, but without avail. Roused to fury by the steady increase of settlement north as well as south of the Ohio, the savages were making life a torment to the borderers. War seemed alone the remedy. In June, General Charles Scott, of Kentucky, raided the Miami and Wabash Indians. Two months later General James Wilkinson, with five hundred Kentuckians, laid waste a Miami village and captured many prisoners. These were intended but to open the road for an expedition of far greater proportions. In October, Governor Arthur St. Clair, of the Northwest Territory, a broken-down man unequal to such a task, was despatched against the Miami towns with an ill-organized army of two thousand raw troops. Upon the fourth of November they were surprised near the principal Miami village; hundreds of the men fled at the first alarm, and of those who remained over six hundred fell during the engagement, while nearly three hundred were wounded. This disastrous termination of the campaign demoralized the West and left the entire border again open to attack — an advantage which the scalping parties did not neglect.

While this disaster was occurring, Boone was again sitting in the legislature at Richmond, where he represented Kanawha County from October 17th to December 20th. The journals of the Assembly show him to have been a silent member, giving voice only in yea and nay; but he was placed upon two then important committees — religion, and propositions and licenses. It was voted to send ammunition for the militia on the Monongahela and the Kanawha, who were to be called out for the defense of the frontier. Before leaving Richmond, Boone wrote as follows to the governor:

“Monday 13th Dec 1791

“Sir as sum purson Must Carry out the armantstion [ammunition] to Red Stone [Brownsville, Pa.,] if your Exclency should have thought me a proper purson I would undertake it on conditions I have the apintment to vitel the company at Kanhowway [Kanawha] so that I Could take Down the flowre as I paste that place I am your Excelenceys most obedent omble servant”

“Dal Boone.”

Five days later the contract was awarded to him; and we find among his papers receipts, obtained at several places on his way home, for the lead and flints which he was to deliver to the various military centers. But the following May, Colonel George Clendennin sharply complains to the governor that the ammunition and rations which Boone was to have supplied to Captain Caperton’s rangers had not yet been delivered, and that Clendennin was forced to purchase these supplies from others. It does not appear from the records how this matter was settled; but as there seems to have been no official inquiry, the non-delivery was probably the result of a misunderstanding.

At last, after a quarter of a century of bloodshed, the United States Government was prepared to act in an effective manner. General Anthony Wayne — “Mad Anthony,” of Stony Point — after spending a year and a half in reorganizing the Western army, established himself, in the winter of 1793-94, in a log fort at Greenville, eighty miles north of Cincinnati, and built a strong outpost at Fort Recovery, on the scene of St. Clair’s defeat. After resisting an attack on Fort Recovery made on the last day of June by over two thousand painted warriors from the Upper Lakes, he advanced with his legion of about three thousand well-disciplined troops to the Maumee Valley and built Fort Defiance. Final battle was given to the tribesmen on the twentieth of August at Fallen Timbers. As the result of superb charges by infantry and cavalry, in forty minutes the Indian army was defeated and scattered. The backbone of savage opposition to Northwestern settlement was broken, and at the treaty of Greenville in the following summer (1795) a peace was secured which remained unbroken for fifteen years.

Wayne’s great victory over the men of the wilderness gave new heart to Kentucky and the Northwest. The pioneers were exuberant in the expression of their joy. The long war, which had lasted practically since the mountains were first crossed by Boone and Finley, had been an almost constant strain upon the resources of the country. Now no longer pent up within palisades, and expecting nightly to be awakened by the whoops of savages to meet either slaughter or still more dreaded captivity, men could go forth without fear to open up forests, to cultivate fields, and peaceably to pursue the chase.

To hunters like Boone, in particular, this great change in their lives was a matter for rejoicing. The Kanawha Valley was not as rich in game as he had hoped; but in Kentucky and Ohio were still large herds of buffaloes and deer feeding on the cane-brake and the rank vegetation of the woods, and resorting to the numerous salt-licks which had as yet been uncontaminated by settlement.

After the peace, Boone for several seasons devoted himself almost exclusively to hunting; in beaver-trapping he was especially successful, his favorite haunt for these animals being the neighboring Valley of the Gauley. His game he shared freely with neighbors, now fast increasing in numbers, and the skins and furs were shipped to market, overland or by river, as of old.

Upon removing to the Kanawha, he still had a few claims left in Kentucky, but suits for ejectment were pending over most of these. They were all decided against him, and the remaining lands were sold by the sheriff for taxes, the last of them going in 1798. His failure to secure anything for his children to inherit, was to the last a source of sorrow to Boone.

The Kanawha in time came to be distasteful to him. Settlements above and below were driving away the game, and sometimes his bag was slight; the crowding of population disturbed the serenity which he sought in deep forests; the nervous energy of these newcomers, and the avarice of some of them, annoyed his quiet, hospitable soul; and he fretted to be again free, thinking that civilization cost too much in wear and tear of spirit.

Boone had long looked kindly toward the broad, practically unoccupied lands of forest and plain west of the Mississippi. Adventurous hunters brought him glowing tales of buffaloes, grizzly bears, and beavers to be found there without number. Spain, fearing an assault upon her possessions from Canada, was just now making flattering offers to those American pioneers who should colonize her territory, and by casting their fortunes with her people strengthen them. This opportunity attracted the disappointed man; he thought the time ripe for making a move which should leave the crowd far behind, and comfortably establish him in a country wherein a hunter might, for many years to come, breathe fresh air and follow the chase untrammeled.

In 1796, Daniel Morgan Boone, his oldest son, traveled with other adventurers in boats to St. Charles County, in eastern Missouri, where they took lands under certificates of cession from Charles Dehault Delassus, the Spanish lieutenant-governor of Upper Louisiana, resident at St. Louis. There were four families, all settling upon Femme Osage Creek, six miles above its junction with the Missouri, some twenty-five miles above the town of St. Charles, and forty-five by water from St. Louis.

Thither they were followed, apparently in the spring of 1799, by Daniel Boone and wife and their younger children. The departure of the great hunter, now in his sixty-fifth year, was the occasion for a general gathering of Kanawha pioneers at the home near Charleston. They came on foot, by horseback, and in canoe, from far and near, and bade him a farewell as solemnly affectionate as though he were departing for another world; indeed, Missouri then seemed almost as far away to the West Virginians as the Klondike is to dwellers in the Mississippi basin to-day — a long journey by packhorse or by flatboat into foreign wilds, beyond the great waterway concerning which the imaginations of untraveled men often ran riot.

The hegira of the Boones, from the junction of the Elk and the Kanawha, was accomplished by boats, into which were crowded such of their scant herd of live stock as could be accommodated. Upon the way they stopped at Kentucky towns along the Ohio, either to visit friends or to obtain provisions, and attracted marked attention, for throughout the West Boone was, of course, one of the best-known men of his day. In Cincinnati he was asked why, at his time of life, he left the comforts of an established home again to subject himself to the privations of the frontier. “Too crowded!" he replied with feeling. “I want more elbow-room!”

Arriving at the little Kentucky colony on Femme Osage Creek, where the Spanish authorities had granted him a thousand arpents of land abutting his son’s estate upon the north, he settled down in a little log cabin erected largely by his own hands, for the fourth and last time as a pioneer. He was never again in the Kanawha Valley, and but twice in Kentucky — once to testify as to some old survey-marks made by him, and again to pay the debts which he had left when removing to Point Pleasant.

CHAPTER XV

A SERENE OLD AGE

Missouri’s sparse population at that time consisted largely of Frenchmen, who had taken easily to the yoke of Spain. For a people of easy-going disposition, theirs was an ideal existence. They led a patriarchal life, with their flocks and herds grazing upon a common pasture, and practised a crude agriculture whose returns were eked out by hunting in the limitless forests hard by. For companionship, the crude log cabins in the little settlements were assembled by the banks of the waterways, and there was small disposition to increase tillage beyond domestic necessities. There were practically no taxes to pay; military burdens sat lightly; the local syndic (or magistrate), the only government servant to be met outside of St. Louis, was sheriff, judge, jury, and commandant combined; there were no elections, for representative government was unknown; the fur and lead trade with St. Louis was the sole commerce, and their vocabulary did not contain the words enterprise and speculation.

Here was a paradise for a man of Boone’s temperament, and through several years to come he was wont to declare that, next to his first long hunt in Kentucky, this was the happiest period of his life. On the eleventh of July, 1800, Delassus — a well-educated French gentleman, and a good judge of character — appointed him syndic for the Femme Osage district, a position which the old man held until the cession of Louisiana to the United States. This selection was not only because of his prominence among the settlers and his recognized honesty and fearlessness, but for the reason that he was one of the few among these unsophisticated folk who could make records. In a primitive community like the Femme Osage, Boone may well have ranked as a man of some education; and certainly he wrote a bold, free hand, showing much practise with the pen, although we have seen that his spelling and grammar might have been improved. When the government was turned over to President Jefferson’s commissioner, Delassus delivered to that officer, by request, a detailed report upon the personality of his subordinates, and this is one of the entries in the list of syndics: “Mr. Boone, a respectable old man, just and impartial, he has already, since I appointed him, offered his resignation owing to his infirmities — believing I know his probity, I have induced him to remain, in view of my confidence in him, for the public good.”

Boone’s knowledge did not extend to law-books, but he had a strong sense of justice; and during his four years of office passed upon the petty disputes of his neighbors with such absolute fairness as to win popular approbation. His methods were as primitive and arbitrary as those of an Oriental pasha; his penalties frequently consisted of lashes on the bare back “well laid on;” he would observe no rules of evidence, saying he wished only to know the truth; and sometimes both parties to a suit were compelled to divide the costs and begone. The French settlers had a fondness for taking their quarrels to court; but the decisions of the good-hearted syndic of Femme Osage, based solely upon common sense in the rough, were respected as if coming from a supreme bench. His contemporaries said that in no other office ever held by the great rifleman did he give such evidence of undisguised satisfaction, or display so great dignity as in this rôle of magistrate. Showing newly arrived American immigrants to desirable tracts of land was one of his most agreeable duties; when thus tendering the hospitalities of the country to strangers, it was remarked that our patriarch played the Spanish “don” to perfection.

In October, 1800, Spain agreed to deliver Louisiana to France; but the latter found it impracticable at that time to take possession of the territory. By the treaty of April 30, 1803, the United States, long eager to secure for the West the open navigation of the Mississippi, purchased the rights of France. It was necessary to go through the form, both in New Orleans and in St. Louis, of transfer by Spain to France, and then by France to the United States. The former ceremony took place in St. Louis, the capital of Upper Louisiana, upon the ninth of March, 1804, and the latter upon the following day. Daniel Boone’s authority as a Spanish magistrate ended when the flag of his adopted country was hauled down for the last time in the Valley of the Mississippi.

The coming of the Americans into power was welcomed by few of the people of Louisiana. The French had slight patience with the land-grabbing temper of the “Yankees,” who were eager to cut down the forests, to open up farms, to build towns, to extend commerce, to erect factories — to inaugurate a reign of noise and bustle and avarice. Neither did men of the Boone type — who had become Spanish subjects in order to avoid the crowds, to get and to keep cheap lands, to avoid taxes, to hunt big game, and to live a simple Arcadian life — at all enjoy this sudden crossing of the Mississippi River, which they had vainly hoped to maintain as a perpetual barrier to so-called progress.

Our hero soon had still greater reason for lamenting the advent of the new régime. His sad experience with lands in Kentucky had not taught him prudence. When the United States commission came to examine the titles of Louisiana settlers to the claims which they held, it was discovered that Boone had failed properly to enter the tract which had been ceded to him by Delassus. The signature of the lieutenant-governor was sufficient to insure a temporary holding, but a permanent cession required the approval of the governor at New Orleans; this Boone failed to obtain, being misled, he afterward stated, by the assertion of Delassus that so important an officer as a syndic need not take such precautions, for he would never be disturbed. The commissioners, while highly respecting him, were regretfully obliged under the terms of the treaty to dispossess the old pioneer, who again found himself landless. Six years later (1810) Congress tardily hearkened to his pathetic appeal, backed by the resolutions of the Kentucky legislature, and confirmed his Spanish grant in words of praise for “the man who has opened the way to millions of his fellow men.”

By the time he was seventy years old, Boone’s skill as a hunter had somewhat lessened. His eyes had lost their phenomenal strength; he could no longer perform those nice feats of marksmanship for which in his prime he had attained wide celebrity, and rheumatism made him less agile. But as a trapper he was still unexcelled, and for many years made long trips into the Western wilderness, even into far-off Kansas, and at least once (1814, when eighty years old) to the great game fields of the Yellowstone. Upon such expeditions, often lasting several months, he was accompanied by one or more of his sons, by his son-in-law Flanders Calloway, or by an old Indian servant who was sworn to bring his master back to the Femme Osage dead or alive — for, curiously enough, this wandering son of the wilderness ever yearned for a burial near home.

Beaver-skins, which were his chief desire, were then worth nine dollars each in the St. Louis market. He appears to have amassed a considerable sum from this source, and from the sale of his land grant to his sons, and in 1810 we find him in Kentucky paying his debts. This accomplished, tradition says that he had remaining only fifty cents; but he gloried in the fact that he was at last “square with the world," and returned to Missouri exultant.

The War of 1812-15 brought Indian troubles to this new frontier, and some of the farm property of the younger Boones was destroyed in one of the savage forays. The old man fretted at his inability to assist in the militia organization, of which his sons Daniel Morgan and Nathan were conspicuous leaders; and the state of the border did not permit of peaceful hunting. In the midst of the war he deeply mourned the death of his wife (1813) — a woman of meek, generous, heroic nature, who had journeyed over the mountains with him from North Carolina, and upon his subsequent pilgrimages, sharing all his hardships and perils, a proper helpmeet in storm and calm.

Penniless, and a widower, he now went to live with his sons, chiefly with Nathan, then forty-three years of age. After being first a hunter and explorer, and then an industrious and successful farmer, Nathan had won distinction in the war just closed and entered the regular army, where he reached the rank of lieutenant-colonel and had a wide and thrilling experience in Indian fighting. Daniel Morgan is thought to have been the first settler in Kansas (1827); A. G. Boone, a grandson, was one of the early settlers of Colorado, and prominently connected with Western Indian treaties and Rocky Mountain exploration; and another grandson of the great Kentuckian was Kit Carson, the famous scout for Frémont’s transcontinental expedition.