Louisiana Anthology

Harriet Beecher Stowe.

A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

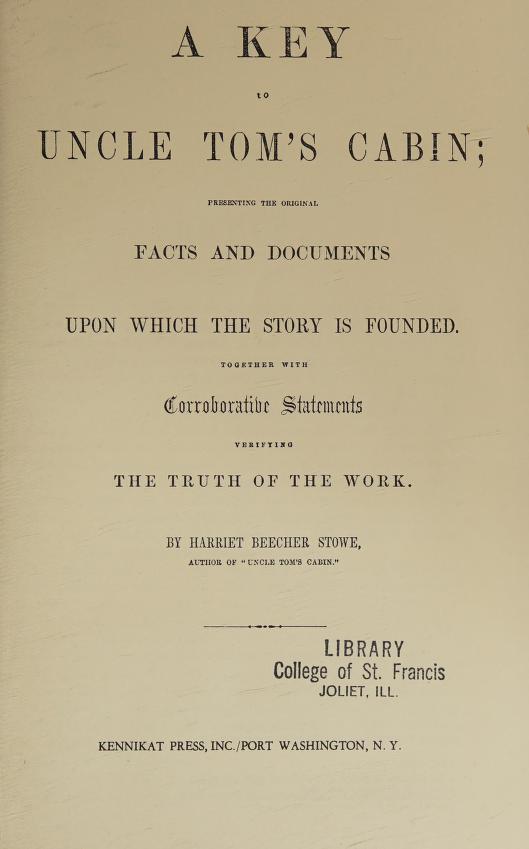

A KEY

TO

UNCLE TOM’S CABIN;

PRESENTING THE ORIGINAL

FACTS AND DOCUMENTS

UPON WHICH THE STORY IS FOUNDED.

TOGETHER WITH

Corroborative Statements

VERIFYING

THE TRUTH OF THE WORK.

BY HARRIET BEECHER STOWE,

AUTHOR OF “UNCLE TOM’S CABIN.”

BOSTON:

PUBLISHED BY JOHN P. JEWETT & CO.

CLEVELAND, OHIO:

JEWETT, PROCTOR & WORTHINGTON.

LONDON:

LOW AND COMPANY.

1853.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1853, by

HARRIET BEECHER STOWE,

In the Clerk’s Office of the District Court for the District of Massachusetts.

STEREOTYPED BY

HOBART & ROBBINS,

NEW ENGLAND TYPE AND STEREOTYPE FOUNDERY,

BOSTON.

Damrell & Moore, Printers, 16 Devonshire St., Boston.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

|

PART I. |

| page

|

| CHAPTER I. — Introduction |

5 |

| |

| CHAPTER II. — Haley. |

5 |

| |

| |

Author’s experience. — Trader’s letter. — Kephart’s examination. — Invoice of human beings. — Various classes of traders. |

|

| |

| CHAPTER III. — Mr. and Mrs. Shelby. |

8 |

| |

| |

Account of a well-regulated plantation. — Extract from Ingraham. |

|

| |

| CHAPTER IV. — George Harris. |

13 |

| |

| |

Advertisements. — Lewis Clark. — Mrs. Banton. — Story of Lewis’ sister. — Mr. Nelson’s story. — Frederick Douglas. — Josiah Henson’s account of the sale of his mother and her children. — Recent incident in Boston. — Advertisements for dead or alive. |

|

| |

| CHAPTER V. — Eliza. |

21 |

| |

| |

Author’s experience. — History of a slave-girl and her escape. |

|

| |

| CHAPTER VI. — Uncle Tom. |

23 |

| |

| |

Similar case. — Old Virginia family servant. — Bishop Meade’s remarks. — Judge Upshur’s servant. — Instance in Brunswick, Me. — History of Josiah Henson. — Uncle Tom’s vision. — Similar facts. — Story of a Boston lady. — Instance of the Southern lady on a plantation. — Story of an African woman. — Account of old Jacob. |

|

| |

| CHAPTER VII. — Miss Ophelia. |

30 |

| |

| |

Prejudice of color — Instance in a benevolent lady. — Dr. Pennington. — Influence of this upon slaveholders. — True Christian socialism. — Amos Lawrence. |

|

| |

| CHAPTER VIII. — Marie St. Clare. |

33 |

| |

| |

The Northern Marie St. Clare. — The Southern Marie St. Clare. — Degrading punishment of females. — Dr. Howe’s account. |

|

| |

| CHAPTER IX. — St. Clare. |

35 |

| |

| |

Alfred and Augustine St. Clare representatives of two classes of men. — Letter of Patrick Henry. — Southern men reproving Northern men. — Mr. Mitchell, of Tennessee. — John Randolph of Roanoke. — Instance of a sceptic made by the Biblical defence of slavery. — Baltimore Sun on Biblical defence of slavery. — Specimen of pro-slavery preaching. |

|

| |

| CHAPTER X. — Legree. |

39 |

| |

| |

No test of character required in a master. — Mr. Dickey’s account in “Slavery as It Is.” — “Working up slaves.” — Extracts from Mr. Weld’s book. — Agricultural society’s testimony. — James G. Birney’s do. — Henry Clay’s do. — Samuel Blackwell’s. — Dr. Demming’s. — Dr. Channing’s. — Rev. Mr. Barrows’. — Rev. C. C. Jones’. — Causes of severe labor on sugar plantations. — Professor Ingraham’s testimony. — Periodical pressure of labor in the cotton season. — Letter of a cotton-driver, published in the Fairfield Herald. — Testimony as to slave-dwellings. — Mr. Stephen E. Maltby. — Mr. George Avery. — William Ladd, Esq. — Rev. Joseph M. Sadd, Esq. — Mr. George W. Westgate. — Rev. C. C. Jones. — Extract from recent letter from a friend travelling in the South. — Extracts with relation to the food of the slaves. — Professor Ingraham’s anecdotes. |

|

| |

| CHAPTER XI. — Select Incidents of Lawful Trade. |

47 |

| |

| |

Separation of an aged mother from her son authenticated. — Selling of the woman to the trader authenticated. — Parting the infant from the mother verified. — Suicide of slaves from grief authenticated. — Parting of “John aged 30” from his wife authenticated. — Case of old Prue in New Orleans authenticated. — Story of the mulatto woman authenticated. |

|

| |

| CHAPTER XII. — Topsy. |

50 |

| |

| |

Effect of the principle of caste upon children. — Letter from Dr. Pennington. — Instance of the Southern lady. — Story of the devoted slave. |

|

| |

| CHAPTER XIII. — The Quakers. |

54 |

| |

| |

Trial of Garret and Hunn. — Imprisonment of Richard Dillingham. — Poetry of Whittier. |

|

| |

| CHAPTER XIV. — Spirit of St. Clare. |

59 |

| |

| |

Containing various testimony from Southern papers and men in favor of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. |

|

|

|

PART II. |

| page

|

| CHAPTER I |

67 |

| |

| |

Accusations of the New York Courier and Enquirer. — Extract from a letter from a gentleman in Richmond, Va., containing various criticisms on slave-law. — Writer’s examination and general conclusion. |

|

| |

| CHAPTER II. — What is Slavery? |

70 |

| |

| |

Definitions from civil code of Louisiana. — From laws of South Carolina. — Decision of Judge Ruffin. — Involve absolute despotism. — Do not admit of humane decisions. — Designed only for the security of the master, with no regard for the welfare of the slave. — Judge Ruffin. — No redress for personal injury that does not produce loss of service. — Case of Cornfute v. Dale. — Decision with regard to patrols. — Decisions of North and South Carolina with respect to the assault and battery of slaves. — Decision in Louisiana, by which, if a person injures a slave, he may, by paying a certain price, become his owner. — Decision in Louisiana, Berard v. Berard, establishing the principle that by no mode of suit, direct or indirect, can a slave obtain redress for ill-treatment. — Case of Jennings v. Fundeberg. — Action for killing negroes. — Also Richardson v. Dukes for the same. — Recognition of the fact that many persons, by withholding from slaves proper food and raiment, cause them to commit crimes for which they are executed. — Is the negro a person in any sense? — Judge Clark’s argument to prove that he is a human being. — Decision that a woman may be given to one person, and her unborn children to another. — Disproportioned punishment of the slave compared with the master. — Case of State v. Mann, showing that the owner or hirer of a slave cannot be punished for indicting cruel, unwarrantable and disproportioned punishments. — Judge Ruffin’s speech. |

|

| |

| CHAPTER III. — Souther v. The Commonwealth, the ne plus ultra of Legal Humanity. |

79 |

| |

| |

Writer’s attention called to this case by Courier and Enquirer. — Case presented. — Writer’s remarks. — Principles established in this case. |

|

| |

| CHAPTER IV. — Protective Statutes. |

83 |

| |

| |

Apprentices protected. — Outlawry. — Melodrama of Prue in the swamp. — Harry the carpenter, a romance of real life. |

|

| |

| CHAPTER V. — Protective Acts of South Carolina and Louisiana. — The Iron Collar of Louisiana and North Carolina. |

87 |

| |

| CHAPTER VI. — Protective Acts with regard to Food and Raiment, Labor, etc. |

90 |

| |

| |

Illustrative drama of Tom v. Legree, under the law of South Carolina. — Separation of parent and child. |

|

| |

| CHAPTER VII. — The Execution of Justice. |

92 |

| |

| |

State v. Eliza Rowand. — The “Ægis of protection” to the slave’s life. |

|

| |

| CHAPTER VIII. — The Good Old Times. |

99 |

| |

| CHAPTER IX. — Moderate Correction and Accidental Death. — State v. Castleman. |

100 |

| |

| CHAPTER X. — Principles established. — State v. Legree; a Case not in the Books. |

103 |

| |

| CHAPTER XI. — The Triumph of Justice over Law. |

104 |

| |

| CHAPTER XII. — A Comparison of the Roman Law of Slavery with the American. |

107 |

| |

| CHAPTER XIII. — The Men better than their Laws. |

110 |

| |

| CHAPTER XIV. — The Hebrew Slave-law compared with the American Slave-law. |

115 |

| |

| CHAPTER XV. — Slavery is Despotism. |

120 |

|

|

PART III. |

| page

|

| CHAPTER I. — Does Public Opinion protect the Slave? |

124 |

| |

| CHAPTER II. — Public Opinion formed by Education. |

129 |

| |

| |

Early training. — “The spirit of the press.” |

|

| |

| CHAPTER III. — Separation of Families. |

133 |

| |

| |

The facts in the case. — Humane dealers. — The exigences of trade. |

|

| |

| CHAPTER IV. — The Slave-trade. |

143 |

| |

| |

What sustains slavery? — The FACTS again, and the comments of Southern men. — The poetry of the slave-trade. |

|

| |

| CHAPTER V. — Select Incidents of Lawful Trade; or, Facts stranger than Fiction. |

151 |

| |

| |

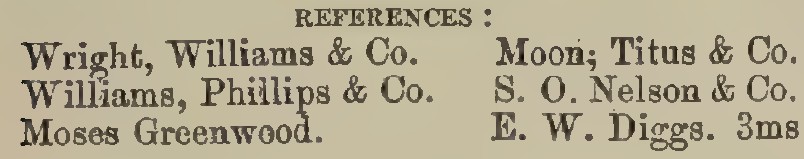

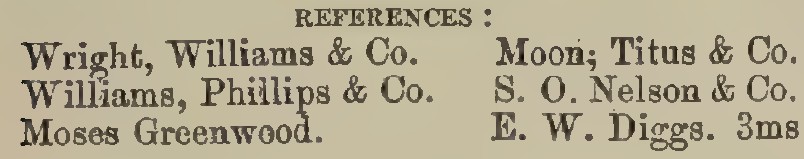

What “domestic sensibilities” Violet and George had. — Testimony of a sea-captain, and of a fugitive slave. |

|

| |

| CHAPTER VI. — The Edmondson Family. |

155 |

| |

| |

Old Milly and her household. — Liberty and equality. — The schooner Pearl. — An American slave-ship. — Capture of fugitives. — Indignation. — Captives imprisoned. — Voyage to New Orleans and return. — Affecting incidents. — Final redemption. |

|

| |

| CHAPTER VII. — Emily Russell. |

168 |

| |

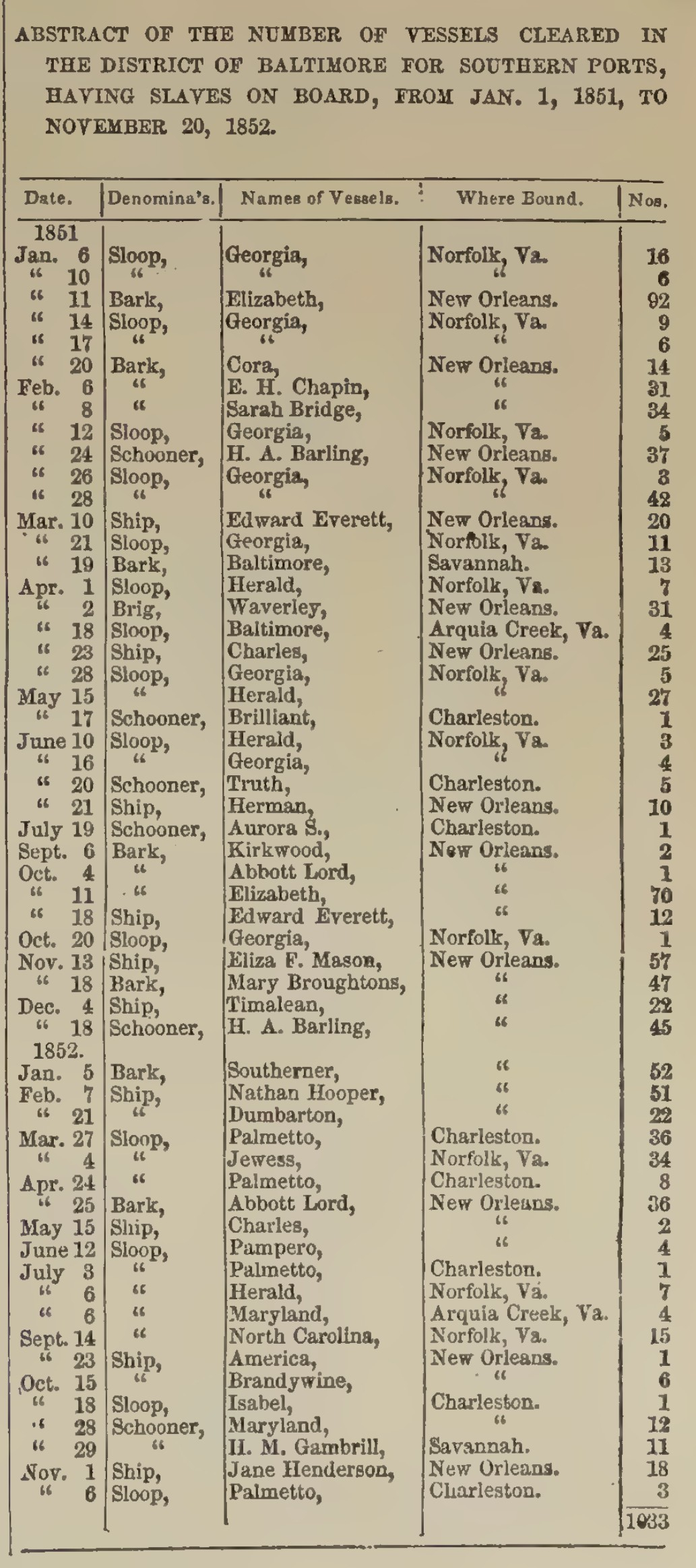

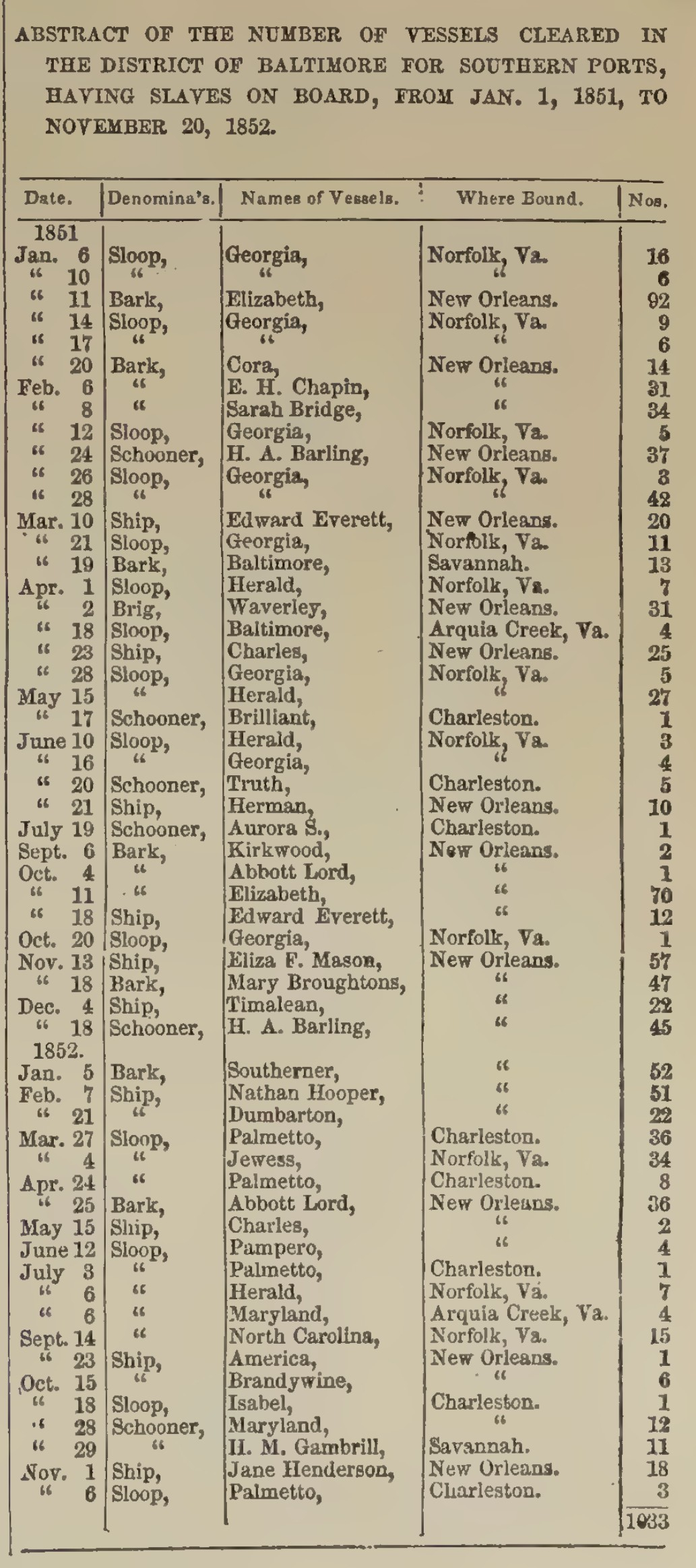

| |

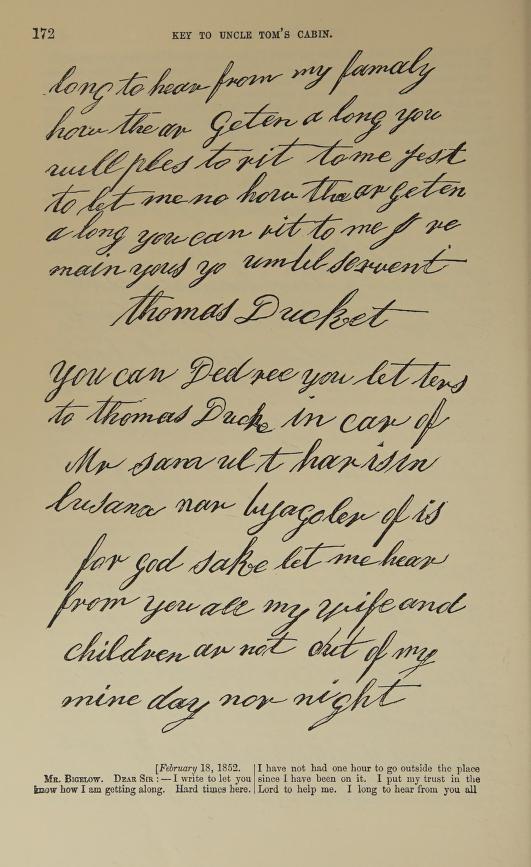

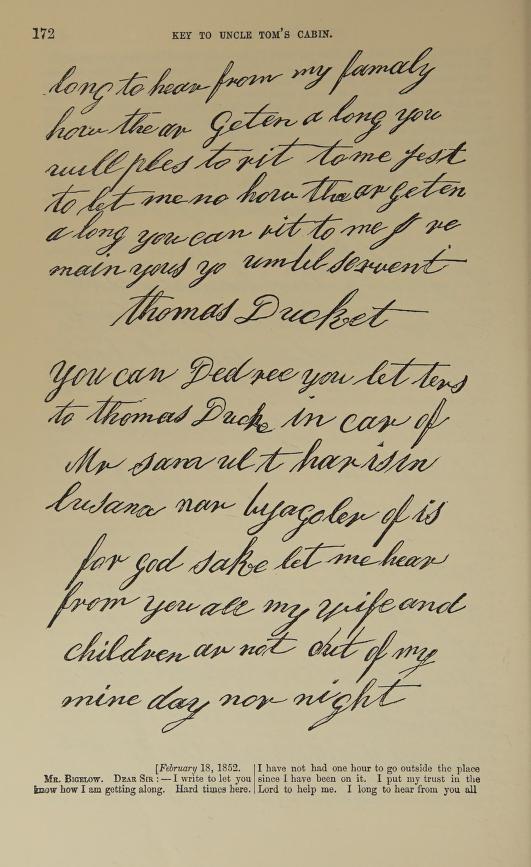

Price of her redemption. — Not raised. — Sent to the South. — Redeemed by death. — Daniel Bell and family. — Poor Tom Ducket. — Facsimile of his letter. |

|

| |

| CHAPTER VIII. — Kidnapping. |

173 |

| |

| |

Causes which lead to kidnapping free negroes and whites. — Solomon Northrop kidnapped. — Carried to Red river. — Parallel to Uncle Tom. — Rachel Parker and sister. |

|

| |

| CHAPTER IX. — Slaves as they are, on Testimony of Owners. |

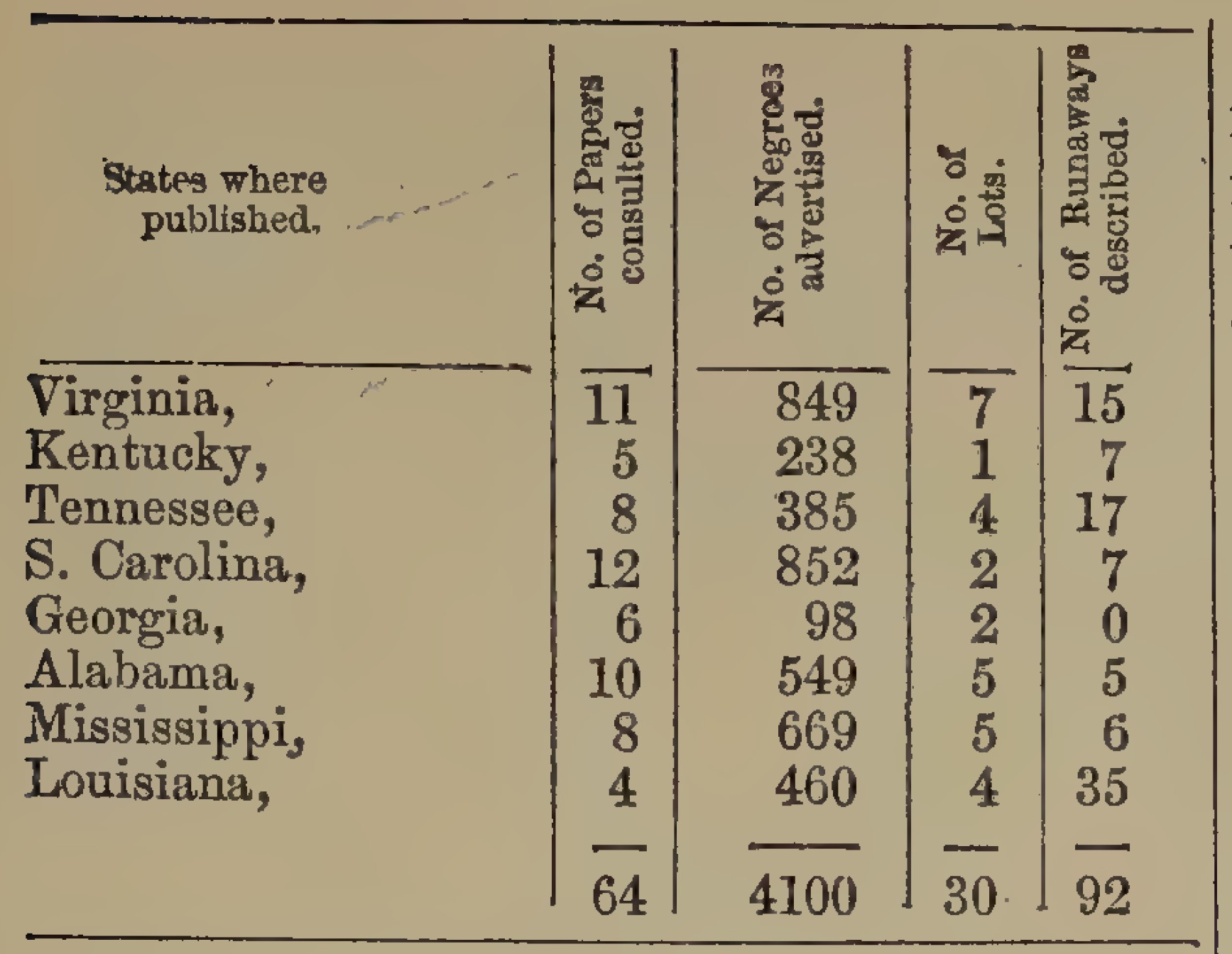

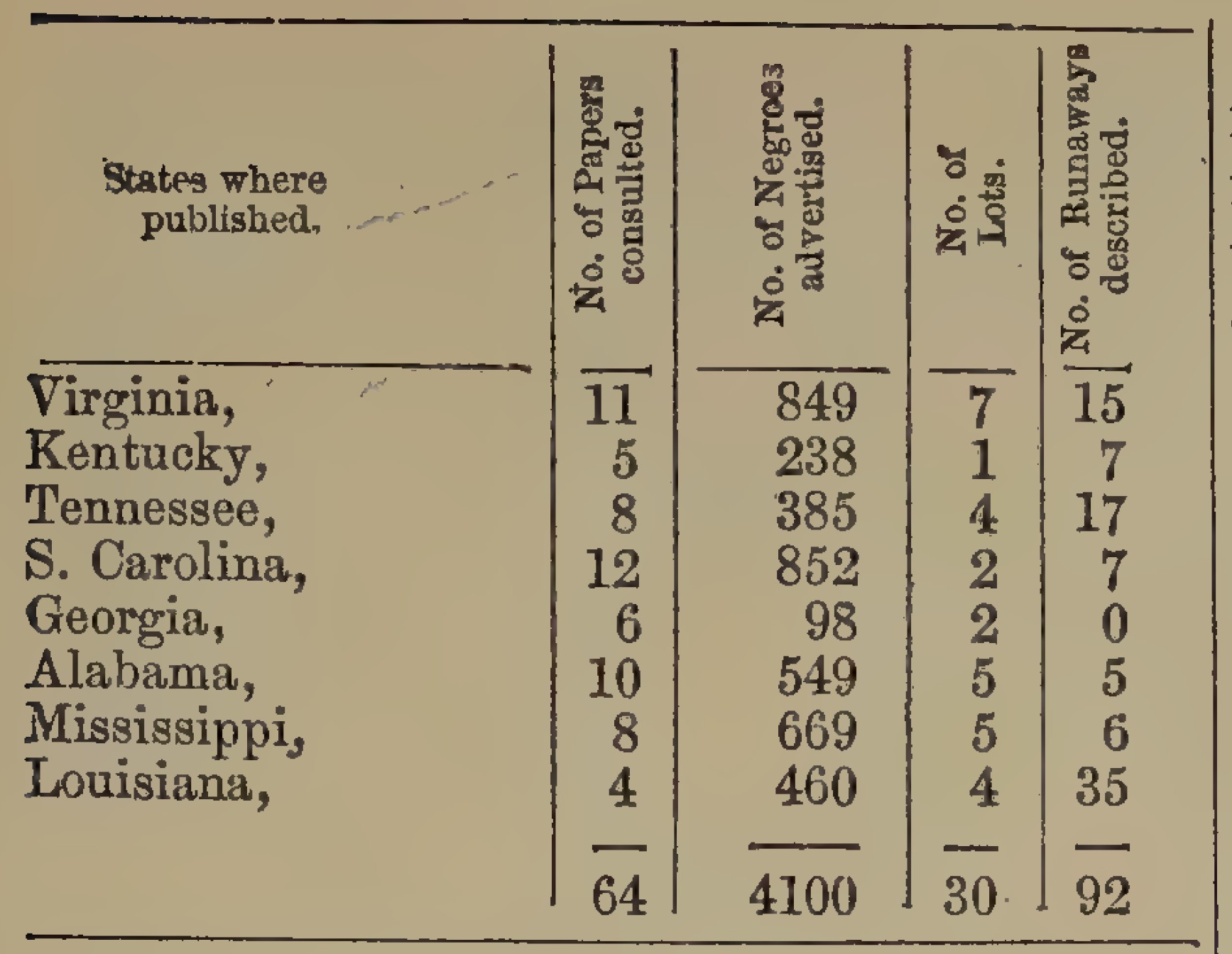

175 |

| |

| |

Color and complexion. — Scars. — Intelligence. — Sale of those claiming to be free. — Illustrated by advertisements. — Inferences. |

|

| |

| CHAPTER X. — Poor White Trash. |

184 |

| |

| |

Slavery degrades the poor whites. — Causes and process. — Materials for mobs. — Fierce for slavery. — Influence of slavery on education. — Emigration from slave states. — N. B. Watson advertised for a hunt. — John Cornutt lynched. — No defence in law. — Justice prostrate. — Rev. E. Matthews lynched. — Case of Jesse McBride. |

|

|

|

PART IV. |

| page

|

| CHAPTER I. — Influence of the American Church on Slavery. |

193 |

| |

| |

Power of the clergy. — The church, what? — Influence. — Points self-evident. — Course of ecclesiastical bodies. — Sanction of American slavery, as it is, by Southern bodies. — Summary of results. |

|

| |

| CHAPTER II. — American Church and Slavery. |

205 |

| |

| |

Trials for heresy. — Course as to slavery heresies. — Course of the Methodist Church. — Course of the Presbyterian Church, before the division. — Course of the Old School body. — Course of the New School body. — Results. — Congregationalists. — Albany convention. — Home Missionary Society. — The protesting power. — Practical workings of the general system. — Pleas for inaction. — Appeal to the church. |

|

| |

| CHAPTER III. — Martyrdom. |

223 |

| |

| |

Power of Leviathan. — He cares more for deeds than words. — E. P. Lovejoy at St. Louis. — At Alton. — Convention. — Speech. — Mob. — Death. |

|

| |

| CHAPTER IV. — Servitude in the Primitive Church compared with American Slavery. |

228 |

| |

| |

Fundamental principles of the kingdom of Christ. — Relations to slavery. — Apostolic directions. — Case of Onesimus. |

|

| |

| CHAPTER V. — Teachings and Condition of the Apostles. |

234 |

| |

| |

Apostles and primitive Christians not law-makers. — Preaching of modern law-makers. |

|

| |

| CHAPTER VI. — Apostolic Teaching on Emancipation. |

235 |

| |

| CHAPTER VII. — Abolition of Slavery by Christianity. |

237 |

| |

| |

State of society. — Course of councils. — Influence of bishops for freedom. — Redemption of captives. — Contrast. |

|

| |

| CHAPTER VIII. — Justice and Equity versus Slavery. |

241 |

| |

| |

Regulation of slavery impossible. — Contrast of its principles and provisions with justice and equity. |

|

| |

| CHAPTER IX. — Is the System of Religion which is taught the Slave the Gospel? |

244 |

| |

| |

Points to be conceded. — What is taught? — Principles and discussion. — Necessary results of the system. — Specimens of teaching and criticisms. |

|

| |

| CHAPTER X. — What is to be done? |

250 |

| |

| |

Work of the church in America. — Feelings of Christians in all other countries. — Eradication of caste, and repeal of sinful laws against free colored people. — Various duties and measures as to slavery. — Closing appeal. |

|

PREFACE.

The work which the writer here presents to the public is one which has

been written with no pleasure, and with much pain.

In fictitious writing, it is possible to find refuge from the hard and the

terrible, by inventing scenes and characters of a more pleasing nature. No

such resource is open in a work of fact; and the subject of this work is one

on which the truth, if told at all, must needs be very dreadful. There is no

bright side to slavery, as such. Those scenes which are made bright by the

generosity and kindness of masters and mistresses, would be brighter still if

the element of slavery were withdrawn. There is nothing picturesque or

beautiful, in the family attachment of old servants, which is not to be found

in countries where these servants are legally free. The tenants on an English

estate are often more fond and faithful than if they were slaves. Slavery,

therefore, is not the element which forms the picturesque and beautiful of

Southern life. What is peculiar to slavery, and distinguishes it from free

servitude, is evil, and only evil, and that continually.

In preparing this work, it has grown much beyond the author’s original

design. It has so far overrun its limits that she has been obliged to omit

one whole department; — that of the characteristics and developments of

the colored race in various countries and circumstances. This is more

properly the subject for a volume; and she hopes that such an one will

soon be prepared by a friend to whom she has transferred her materials.

The author desires to express her thanks particularly to those legal

gentlemen who have given her their assistance and support in the legal part

of the discussion. She also desires to thank those, at the North and at the

South, who have kindly furnished materials for her use. Many more have

been supplied than could possibly be used. The book is actually selected

out of a mountain of materials.

The great object of the author in writing has been to bring this subject of

slavery, as a moral and religious question, before the minds of all those who

profess to be followers of Christ, in this country. A minute history has

been given of the action of the various denominations on this subject.

The writer has aimed, as far as possible, to say what is true, and only

that, without regard to the effect which it may have upon any person or

party. She hopes that what she has said will be examined without bitterness, — in

that serious and earnest spirit which is appropriate for the

examination of so very serious a subject. It would be vain for her to

indulge the hope of being wholly free from error. In the wide field which

she has been called to go over, there is a possibility of many mistakes. She

can only say that she has used the most honest and earnest endeavors to

learn the truth.

The book is commended to the candid attention and earnest prayers of

all true Christians, throughout the world. May they unite their prayers

that Christendom may be delivered from so great an evil as slavery!

At different times, doubt has been expressed

whether the representations of

“Uncle Tom’s Cabin” are a fair representation

of slavery as it at present exists.

This work, more, perhaps, than any other

work of fiction that ever was written,

has been a collection and arrangement of

real incidents, — of actions really performed,

of words and expressions really

uttered, — grouped together with reference

to a general result, in the same manner

that the mosaic artist groups his fragments

of various stones into one general picture.

His is a mosaic of gems, — this is a mosaic

of facts.

Artistically considered, it might not be

best to point out in which quarry and from

which region each fragment of the mosaic

picture had its origin; and it is equally unartistic

to disentangle the glittering web of

fiction, and show out of what real warp and

woof it is woven, and with what real coloring

dyed. But the book had a purpose entirely

transcending the artistic one, and

accordingly encounters, at the hands of the

public, demands not usually made on fictitious

works. It is treated as a reality, — sifted,

tried and tested, as a reality; and

therefore as a reality it may be proper

that it should be defended.

The writer acknowledges that the book is

a very inadequate representation of slavery;

and it is so, necessarily, for this reason, — that

slavery, in some of its workings, is too

dreadful for the purposes of art. A work

which should represent it strictly as it is

would be a work which could not be read.

And all works which ever mean to give

pleasure must draw a veil somewhere, or

they cannot succeed.

The author will now proceed along the

course of the story, from the first page onward,

and develop, as far as possible, the

incidents by which different parts were

suggested.

In the very first chapter of the book we

encounter the character of the negro-trader,

Mr. Haley. His name stands at the head

of this chapter as the representative of all

the different characters introduced in the

work which exhibit the trader, the kidnapper,

the negro-catcher, the negro-whipper,

and all the other inevitable auxiliaries and

indispensable appendages of what is often

called the “divinely-instituted relation”

of slavery. The author’s first personal

observation of this class of beings was somewhat

as follows:

Several years ago, while one morning

employed in the duties of the nursery, a

colored woman was announced. She was

ushered into the nursery, and the author

thought, on first survey, that a more surly,

unpromising face she had never seen. The

woman was thoroughly black, thick-set,

firmly built, and with strongly-marked African

features. Those who have been accustomed

to read the expressions of the

African face know what a peculiar effect is

produced by a lowering, desponding expression

upon its dark features. It is like the

shadow of a thunder-cloud. Unlike her

race generally, the woman did not smile

when smiled upon, nor utter any pleasant

remark in reply to such as were addressed

to her. The youngest pet of the nursery,

a boy about three years old, walked up, and

laid his little hand on her knee, and seemed

astonished not to meet the quick smile which

the negro almost always has in reserve for

the little child. The writer thought her

very cross and disagreeable, and, after a few

moments’ silence, asked, with perhaps a

little impatience, “Do you want anything

of me to-day?”

“Here are some papers,” said the woman,

pushing them towards her; “perhaps

you would read them.”

The first paper opened was a letter from

a negro-trader in Kentucky, stating concisely

that he had waited about as long as

he could for her child; that he wanted to

start for the South, and must get it off

his hands; that, if she would send him

two hundred dollars before the end of the

week, she should have it; if not, that he

would set it up at auction, at the court-house

door, on Saturday. He added, also,

that he might have got more than that for

the child, but that he was willing to let her

have it cheap.

“What sort of a man is this?” said the

author to the woman, when she had done

reading the letter.

“Dunno, ma’am; great Christian, I

know, — member of the Methodist church,

anyhow.”

The expression of sullen irony with which

this was said was a thing to be remembered.

“And how old is this child?” said the

author to her.

The woman looked at the little boy who

had been standing at her knee, with an expressive

glance, and said, “She will be

three years old this summer.”

On further inquiry into the history of

the woman, it appeared that she had been

set free by the will of her owners; that

the child was legally entitled to freedom,

but had been seized on by the heirs of

the estate. She was poor and friendless,

without money to maintain a suit, and the

heirs, of course, threw the child into the

hands of the trader. The necessary sum, it

may be added, was all raised in the small

neighborhood which then surrounded the

Lane Theological Seminary, and the child

was redeemed.

If the public would like a specimen of

the correspondence which passes between

these worthies, who are the principal reliance

of the community for supporting and

extending the institution of slavery, the following

may be interesting as a matter of

literary curiosity. It was forwarded by

Mr. M. J. Thomas, of Philadelphia, to the

National Era, and stated by him to be “a

copy taken verbatim from the original,

found among the papers of the person to

whom it was addressed, at the time of his

arrest and conviction, for passing a variety

of counterfeit bank-notes.”

Poolsville, Montgomery Co., Md.,

March 24, 1831.

Dear Sir: I arrived home in safety with Louisa,

John having been rescued from me, out of a

two-story window, at twelve o’clock at night. I

offered a reward of fifty dollars, and have him here

safe in jail. The persons who took him brought

him to Fredericktown jail. I wish you to write to

no person in this state but myself. Kephart and

myself are determined to go the whole hog for any

negro you can find, and you must give me the earliest

information, as soon as you do find any. Enclosed

you will receive a handbill, and I can make

a good bargain, if you can find them. I will in

all cases, as soon as a negro runs off, send you a

handbill immediately, so that you may be on the

look-out. Please tell the constable to go on with

the sale of John’s property; and, when the money

is made, I will send on an order to you for it.

Please attend to this for me; likewise write to me,

and inform me of any negro you think has run away, — no

matter where you think he has come from,

nor how far, — and I will try and find out his master.

Let me know where you think he is from,

with all particular marks, and if I don’t find his

master, Joe’s dead!

Write to me about the crooked-fingered negro,

and let me know which hand and which finger,

color, &c.; likewise any mark the fellow has who

says he got away from the negro-buyer, with his

height and color, or any other you think has

run off.

Give my respects to your partner, and be sure

you write to no person but myself. If any person

writes to you, you can inform me of it, and I will

try to buy from them. I think we can make money,

if we do business together; for I have plenty

of money, if you can find plenty of negroes. Let

me know if Daniel is still where he was, and if

you have heard anything of Francis since I left

you. Accept for yourself my regard and esteem.

Reuben B. Carlley.

This letter strikingly illustrates the

character of these fellow-patriots with

whom the great men of our land have been

acting in conjunction, in carrying out the

beneficent provisions of the Fugitive Slave

Law.

With regard to the Kephart named in

this letter the community of Boston may

have a special interest to know further particulars,

as he was one of the dignitaries

sent from the South to assist the good citizens

of that place in the religious and patriotic

enterprise of 1851, at the time that

Shadrach was unfortunately rescued. It

therefore may be well to introduce somewhat

particularly John Kephart, as sketched

by Richard H. Dana, Jr., one of the

lawyers employed in the defence of the perpetrators

of the rescue.

I shall never forget John Caphart. I have been

eleven years at the bar, and in that time have seen

many developments of vice and hardness, but I

never met with anything so cold-blooded as the

testimony of that man. John Caphart is a tall,

sallow man, of about fifty, with jet-black hair, a

restless, dark eye, and an anxious, care-worn

look, which, had there been enough of moral element

in the expression, might be called melancholy.

His frame was strong, and in youth he

had evidently been powerful, but he was not robust.

Yet there was a calm, cruel look, a power

of will and a quickness of muscular action, which

still render him a terror in his vocation.

In the manner of giving in his testimony there

was no bluster or outward show of insolence. His

contempt for the humane feelings of the audience

and community about him was too true to require

any assumption of that kind. He neither paraded

nor attempted to conceal the worst features of his

calling. He treated it as a matter of business

which he knew the community shuddered at, but

the moral nature of which he was utterly indifferent

to, beyond a certain secret pleasure in thus

indirectly inflicting a little torture on his hearers.

I am not, however, altogether clear, to do John

Caphart justice, that he is entirely conscience-proof.

There was something in his anxious look

which leaves one not without hope.

At the first trial we did not know of his pursuits,

and he passed merely as a police-man of

Norfolk, Virginia. But, at the second trial, some

one in the room gave me a hint of the occupations

many of these police-men take to, which led to my

cross-examination.

From the Examination of John Caphart, in the

“Rescue Trials,” at Boston, in June and Nov.,

1851, and October, 1852.

Question. Is it a part of your duty, as a police-man,

to take up colored persons who are out after

hours in the streets?

Answer. Yes, sir.

Q. What is done with them?

A. We put them in the lock-up, and in the

morning they are brought into court and ordered

to be punished, — those that are to be

punished.

Q. What punishment do they get?

A. Not exceeding thirty-nine lashes.

Q. Who gives them these lashes?

A. Any of the officers. I do, sometimes.

Q. Are you paid extra for this? How much?

A. Fifty cents a head. It used to be sixty-two

cents. Now it is fifty. Fifty cents for each one

we arrest, and fifty more for each one we flog.

Q. Are these persons you flog men and boys

only, or are they women and girls also?

A. Men, women, boys and girls, just as it happens.

[The government interfered, and tried to prevent

any further examination; and said, among

other things, that he only performed his duty as

police-officer under the law. After a discussion,

Judge Curtis allowed it to proceed.]

Q. Is your flogging confined to these cases?

Do you not flog slaves at the request of their

masters?

A. Sometimes I do. Certainly, when I am

called upon.

Q. In these cases of private flogging, are the

negroes sent to you? Have you a place for

flogging?

A. No. I go round, as I am sent for.

Q. Is this part of your duty as an officer?

A. No, sir.

Q. In these cases of private flogging, do you

inquire into the circumstances, to see what the

fault has been, or if there is any?

A. That’s none of my business. I do as I am

requested. The master is responsible.

Q. In these cases, too, I suppose you flog women

and girls, as well as men.

A. Women and men.

Q. Mr. Caphart, how long have you been engaged

in this business?

A. Ever since 1836.

Q. How many negroes do you suppose you have

flogged, in all, women and children included?

A. [Looking calmly round the room.] I don’t

know how many niggers you have got here in Massachusetts,

but I should think I had flogged as many

as you’ve got in the state.

[The same man testified that he was often employed

to pursue fugitive slaves. His reply to

the question was, “I never refuse a good job in

that line.”]

Q. Don’t they sometimes turn out bad jobs?

A. Never, if I can help it.

Q. Are they not sometimes discharged after

you get them?

A. Not often. I don’t know that they ever are,

except those Portuguese the counsel read about.

[I had found, in a Virginia report, a case of

some two hundred Portuguese negroes, whom this

John Caphart had seized from a vessel, and endeavored

to get condemned as slaves, but whom

the court discharged.]

Hon. John P. Hale, associated with Mr.

Dana, as counsel for the defence, in the

Rescue Trials, said of him, in his closing

argument:

Why, gentlemen, he sells agony! Torture is

his stock-in-trade! He is a walking scourge!

He hawks, peddles, retails, groans and tears about

the streets of Norfolk!

See also the following correspondence

between two traders, one in North Carolina,

the other in New Orleans; with a word of

comment, by Hon. William Jay, of New

York:

Halifax, N. C., Nov. 16, 1839.

Dear Sir: I have shipped in the brig Addison, — prices

are below:

| No. 1. Caroline Ennis, |

$650.00 |

| No. 2. Silvy Holland, |

625.00 |

| No. 3. Silvy Booth, |

487.50 |

| No. 4. Maria Pollock, |

475.00 |

| No. 5. Emeline Pollock, |

475.00 |

| No. 6. Delia Averit, |

475.00 |

The two girls that cost $650 and $625 were

bought before I shipped my first. I have a great

many negroes offered to me, but I will not pay the

prices they ask, for I know they will come down.

I have no opposition in market. I will wait until

I hear from you before I buy, and then I can

judge what I must pay. Goodwin will send you

the bill of lading for my negroes, as he shipped

them with his own. Write often, as the times

are critical, and it depends on the prices you get

to govern me in buying. Yours, &c.,

G. W. Barnes.

| Mr. Theophilus Freeman, |

} |

| New Orleans. |

The above was a small but choice invoice of

wives and mothers. Nine days before, namely,

7th Nov., Mr. Barnes advised Mr. Freeman of

having shipped a lot of forty-three men and

women. Mr. Freeman, informing one of his correspondents

of the state of the market, writes

(Sunday, 21st Sept., 1839), “I bought a boy yesterday,

sixteen years old, and likely, weighing

one hundred and ten pounds, at $700. I sold a

likely girl, twelve years old, at $500. I bought a

man yesterday, twenty years old, six feet high, at

$820; one to-day, twenty-four years old, at $850,

black and sleek as a mole.”

The writer has drawn in this work only

one class of the negro-traders. There are

all varieties of them, up to the great wholesale

purchasers, who keep their large trading-houses;

who are gentlemanly in manners

and courteous in address; who, in many

respects, often perform actions of real generosity;

who consider slavery a very great

evil, and hope the country will at some

time be delivered from it, but who think

that so long as clergyman and layman, saint

and sinner, are all agreed in the propriety

and necessity of slave-holding, it is better

that the necessary trade in the article be

conducted by men of humanity and decency,

than by swearing, brutal men, of the Tom

Loker school. These men are exceedingly

sensitive with regard to what they consider

the injustice of the world in excluding them

from good society, simply because they undertake

to supply a demand in the community

which the bar, the press and the

pulpit, all pronounce to be a proper one. In

this respect, society certainly imitates the

unreasonableness of the ancient Egyptians,

who employed a certain class of men to

prepare dead bodies for embalming, but

flew at them with sticks and stones the moment

the operation was over, on account of

the sacrilegious liberty which they had

taken. If there is an ill-used class of men

in the world, it is certainly the slave-traders;

for, if there is no harm in the institution

of slavery, — if it is a divinely-appointed

and honorable one, like civil government

and the family state, and like other species of

property relation, — then there is no earthly

reason why a man may not as innocently

be a slave-trader as any other kind of

trader.

It was the design of the writer, in delineating

the domestic arrangements of Mr.

and Mrs. Shelby, to show a picture of the

fairest side of slave-life, where easy indulgence

and good-natured forbearance are tempered

by just discipline and religious instruction,

skilfully and judiciously imparted.

The writer did not come to her task without

reading much upon both sides of the

question, and making a particular effort to

collect all the most favorable representations

of slavery which she could obtain.

And, as the reader may have a

curiosity to examine some of the documents,

the writer will present them quite at large.

There is no kind of danger to the world in

letting the very fairest side of slavery be

seen; in fact, the horrors and barbarities

which are necessarily inherent in it are so

terrible that one stands absolutely in need

of all the comfort which can be gained from

incidents like the subjoined, to save them

from utter despair of human nature. The first

account is from Mr. J. K. Paulding’s Letters

on Slavery; and is a letter from a Virginia

planter, whom we should judge, from his

style, to be a very amiable, agreeable man,

and who probably describes very fairly the

state of things on his own domain.

Dear Sir: As regards the first query, which

relates to the “rights and duties of the slave,” I

do not know how extensive a view of this branch

of the subject is contemplated. In its simplest

aspect, as understood and acted on in Virginia, I

should say that the slave is entitled to an abundance

of good plain food; to coarse but comfortable

apparel; to a warm but humble dwelling; to protection

when well, and to succor when sick; and,

in return, that it is his duty to render to his master

all the service he can consistently with perfect

health, and to behave submissively and honestly.

Other remarks suggest themselves, but

they will be more appropriately introduced under

different heads.

2d. “The domestic relations of master and

slave.” — These relations are much misunderstood

by many persons at the North, who regard the

terms as synonymous with oppressor and oppressed.

Nothing can be further from the fact.

The condition of the negroes in this state has

been greatly ameliorated. The proprietors were

formerly fewer and richer than at present. Distant

quarters were often kept up to support the

aristocratic mansion. They were rarely visited

by their owners; and heartless overseers, frequently

changed, were employed to manage them

for a share of the crop. These men scourged the

land, and sometimes the slaves. Their tenure

was but for a year, and of course they made the

most of their brief authority. Owing to the influence

of our institutions, property has become subdivided,

and most persons live on or near their

estates. There are exceptions, to be sure, and

particularly among wealthy gentlemen in the

towns; but these last are almost all enlightened

and humane, and alike liberal to the soil and to

the slave who cultivates it. I could point out

some noble instances of patriotic and spirited improvement

among them. But, to return to the

resident proprietors: most of them have been

raised on the estates; from the older negroes

they have received in infancy numberless acts of

kindness; the younger ones have not unfrequently

been their playmates (not the most suitable, I

admit), and much good-will is thus generated on

both sides. In addition to this, most men feel

attached to their property; and this attachment

is stronger in the case of persons than of things.

I know it, and feel it. It is true, there are harsh

masters; but there are also bad husbands and

bad fathers. They are all exceptions to the rule,

not the rule itself. Shall we therefore condemn

in the gross those relations, and the rights and

authority they imply, from their occasional

abuse? I could mention many instances of strong

attachment on the part of the slave, but will only

adduce one or two, of which I have been the object.

It became a question whether a faithful

servant, bred up with me from boyhood, should

give up his master or his wife and children, to

whom he was affectionately attached, and most

attentive and kind. The trial was a severe one,

but he determined to break those tender ties and

remain with me. I left it entirely to his discretion,

though I would not, from considerations of

interest, have taken for him quadruple the price I

should probably have obtained. Fortunately, in

the sequel, I was enabled to purchase his family,

with the exception of a daughter, happily situated;

and nothing but death shall henceforth part

them. Were it put to the test, I am convinced

that many masters would receive this striking

proof of devotion. A gentleman but a day or two

since informed me of a similar, and even stronger

case, afforded by one of his slaves. As the reward

of assiduous and delicate attention to a venerated

parent, in her last illness, I proposed to purchase

and liberate a healthy and intelligent woman,

about thirty years of age, the best nurse, and, in

all respects, one of the best servants in the state,

of which I was only part owner; but she declined

to leave the family, and has been since rather

better than free. I shall be excused for stating a

ludicrous case I heard of some time ago: — A

favorite and indulged servant requested his master

to sell him to another gentleman. His master refused

to do so, but told him he was at perfect

liberty to go to the North, if he were not already

free enough. After a while he repeated the request;

and, on being urged to give an explanation

of his singular conduct, told his master that he

considered himself consumptive, and would soon

die; and he thought Mr. B—— was better able

to bear the loss than his master. He was sent to

a medicinal spring and recovered his health, if,

indeed, he had ever lost it, of which his master

had been unapprised. It may not be amiss to

describe my deportment towards my servants,

whom I endeavor to render happy while I make

them profitable. I never turn a deaf ear, but

listen patiently to their communications. I chat

familiarly with those who have passed service, or

have not begun to render it. With the others I

observe a more prudent reserve, but I encourage

all to approach me without awe. I hardly ever

go to town without having commissions to execute

for some of them; and think they prefer to employ

me, from a belief that, if their money should

not quite hold out, I would add a little to it; and

I not unfrequently do, in order to get a better

article. The relation between myself and my

slaves is decidedly friendly. I keep up pretty exact

discipline, mingled with kindness, and hardly

ever lose property by thievish, or labor by runaway

slaves. I never lock the outer doors of my

house. It is done, but done by the servants; and

I rarely bestow a thought on the matter. I leave

home periodically for two months, and commit the

dwelling-house, plate, and other valuables, to the

servants, without even an enumeration of the

articles.

3d. “The duration of the labor of the slave.” — The

day is usually considered long enough. Employment

at night is not exacted by me, except to

shell corn once a week for their own consumption,

and on a few other extraordinary occasions. The

people, as we generally call them, are required to

leave their houses at daybreak, and to work until

dark, with the intermission of half an hour to an

hour at breakfast, and one to two hours at dinner,

according to the season and sort of work. In this

respect I suppose our negroes will bear a favorable

comparison with any laborers whatever.

4th. “The liberty usually allowed the slave, — his

holidays and amusements, and the way in

which they usually spend their evenings and holidays.” — They

are prohibited from going off the

estate without first obtaining leave; though they

often transgress, and with impunity, except in

flagrant cases. Those who have wives on other

plantations visit them on certain specified nights,

and have an allowance of time for going and returning,

proportioned to the distance. My negroes

are permitted, and, indeed, encouraged, to

raise as many ducks and chickens as they can; to

cultivate vegetables for their own use, and a patch

of corn for sale; to exercise their trades, when

they possess one, which many do; to catch muskrats

and other animals for the fur or the flesh; to

raise bees, and, in fine, to earn an honest penny

in any way which chance or their own ingenuity

may offer. The modes specified are, however,

those most commonly resorted to, and enable provident

servants to make from five to thirty dollars

apiece. The corn is of a different sort from that

which I cultivate, and is all bought by me. A

great many fowls are raised; I have this year

known ten dollars worth sold by one man at one

time. One of the chief sources of profit is the

fur of the muskrat; for the purpose of catching

which the marshes on the estate have been parcelled

out and appropriated from time immemorial,

and are held by a tenure little short of fee-simple.

The negroes are indebted to Nat Turner[1]

and Tappan for a curtailment of some of their

privileges. As a sincere friend to the blacks, I

have much regretted the reckless interference of

these persons, on account of the restrictions it has

become, or been thought, necessary to impose.

Since the exploit of the former hero, they have

been forbidden to preach, except to their fellow-slaves,

the property of the same owner; to have

public funerals, unless a white person officiates;

or to be taught to read and write. Their funerals

formerly gave them great satisfaction, and it was

customary here to furnish the relations of the deceased

with bacon, spirit, flour, sugar and butter,

with which a grand entertainment, in their way,

was got up. We were once much amused by a

hearty fellow requesting his mistress to let him

have his funeral during his lifetime, when it would

do him some good. The waggish request was

granted; and I venture to say there never was a

funeral the subject of which enjoyed it so much.

When permitted, some of our negroes preached

with great fluency. I was present, a few years

since, when an Episcopal minister addressed the

people, by appointment. On the conclusion of an

excellent sermon, a negro preacher rose and

thanked the gentleman kindly for his discourse,

but frankly told him the congregation “did not

understand his lingo.” He then proceeded himself,

with great vehemence and volubility, coining

words where they had not been made to his hand,

or rather his tongue, and impressing his hearers,

doubtless, with a decided opinion of his superiority

over his white co-laborer in the field of

grace. My brother and I, who own contiguous

estates, have lately erected a chapel on the line

between them, and have employed an acceptable

minister of the Baptist persuasion, to which the

negroes almost exclusively belong, to afford them

religious instruction. Except as a preparatory

step to emancipation, I consider it exceedingly

impolitic, even as regards the slaves themselves,

to permit them to read and write: “Where ignorance

is bliss, ‘tis folly to be wise.” And it is

certainly impolitic as regards their masters, on

the principle that “knowledge is power.” My

servants have not as long holidays as those of

most other persons. I allow three days at

Christmas, and a day at each of three other periods,

besides a little time to work their patches;

or, if very busy, I sometimes prefer to work them

myself. Most of the ancient pastimes have been

lost in this neighborhood, and religion, mock or

real, has succeeded them. The banjo, their national

instrument, is known but in name, or in a

few of the tunes which have survived. Some of

the younger negroes sing and dance, but the

evenings and holidays are usually occupied in

working, in visiting, and in praying and singing

hymns. The primitive customs and sports are, I

believe, better preserved further south, where

slaves were brought from Africa long after they

ceased to come here.

6th. “The provision usually made for their

food and clothing, — for those who are too young

or too old to labor.” — My men receive twelve

quarts of Indian meal (the abundant and universal

allowance in this state), seven salted herrings,

and two pounds of smoked bacon or three

pounds of pork, a week; the other hands proportionally

less. But, generally speaking, their food

is issued daily, with the exception of meal, and

consists of fish or bacon for breakfast, and meat,

fresh or salted, with vegetables whenever we can

provide them, for dinner; or, for a month or two

in the spring, fresh fish cooked with a little bacon.

This mode is rather more expensive to me than

that of weekly rations, but more comfortable to

the servants. Superannuated or invalid slaves

draw their provisions regularly once a week; and

the moment a child ceases to be nourished by its

mother, it receives eight quarts of meal (more than

it can consume), and one half-pound of lard. Besides

the food furnished by me, nearly all the

servants are able to make some addition from

their private stores; and there is among the

adults hardly an instance of one so improvident

as not to do it. He must be an unthrifty fellow,

indeed, who cannot realize the wish of the famous

Henry IV. in regard to the French peasantry, and

enjoy his fowl on Sunday. I always keep on

hand, for the use of the negroes, sugar, molasses,

&c., which, though not regularly issued, are applied

for on the slightest pretexts, and frequently no

pretext at all, and are never refused, except in

cases of misconduct. In regard to clothing: — the

men and boys receive a winter coat and trousers

of strong cloth, three shirts, a stout pair of

shoes and socks, and a pair of summer pantaloons,

every year; a hat about every second year, and a

great-coat and blanket every third year. Instead

of great-coats and hats, the women have large

capes to protect the bust in bad weather, and

handkerchiefs for the head. The articles furnished

are good and serviceable; and, with their

own acquisitions, make their appearance decent

and respectable. On Sunday they are even fine.

The aged and invalid are clad as regularly as the

rest, but less substantially. Mothers receive a

little raw cotton, in proportion to the number of

children, with the privilege of having the yarn,

when spun, woven at my expense. I provide

them with blankets. Orphans are put with careful

women, and treated with tenderness. I am

attached to the little slaves, and encourage familiarity

among them. Sometimes, when I ride

near the quarters, they come running after me with

the most whimsical requests, and are rendered

happy by the distribution of some little donation.

The clothing described is that which is given to

the crop hands. Home-servants, a numerous

class in Virginia, are of course clad in a different

and very superior manner. I neglected to mention,

in the proper place, that there are on each

of my plantations a kitchen, an oven, and one or

more cooks; and that each hand is furnished with

a tin bucket for his food, which is carried into the

field by little negroes, who also supply the laborers

with water.

7th. “Their treatment when sick.” — My negroes

go, or are carried, as soon as they are attacked, to

a spacious and well-ventilated hospital, near the

mansion-house. They are there received by an

attentive nurse, who has an assortment of medicine,

additional bed-clothing, and the command of

as much light food as she may require, either

from the table or the store-room of the proprietor.

Wine, sago, rice, and other little comforts appertaining

to such an establishment, are always

kept on hand. The condition of the sick is much

better than that of the poor whites or free colored

people in the neighborhood.

8th. “Their rewards and punishments.” — I

occasionally bestow little gratuities for good conduct,

and particularly after harvest; and hardly

ever refuse a favor asked by those who faithfully

perform their duty. Vicious and idle servants are

punished with stripes, moderately inflicted; to

which, in the case of theft, is added privation of

meat, a severe punishment to those who are never

suffered to be without it on any other account.

From my limited observation, I think that servants

to the North work much harder than our

slaves. I was educated at a college in one of the

free states, and, on my return to Virginia, was

struck with the contrast. I was astonished at the

number of idle domestics, and actually worried my

mother, much to my contrition since, to reduce

the establishment. I say to my contrition, because,

after eighteen years’ residence in the good

Old Dominion, I find myself surrounded by a troop

of servants about as numerous as that against

which I formerly so loudly exclaimed. While on

this subject it may not be amiss to state a case of

manumission which occurred about three years

since. My nearest neighbor, a man of immense

wealth, owned a favorite servant, a fine fellow,

with polished manners and excellent disposition,

who reads and writes, and is thoroughly versed in

the duties of a butler and housekeeper, in the performance

of which he was trusted without limit.

This man was, on the death of his master, emancipated

with a legacy of six thousand dollars, besides

about two thousand dollars more which he had

been permitted to accumulate, and had deposited

with his master, who had given him credit for it.

The use that this man, apparently so well qualified

for freedom, and who has had an opportunity

of travelling and of judging for himself, makes of

his money and his time, is somewhat remarkable.

In consequence of his exemplary conduct, he has

been permitted to reside in the state, and for very

moderate wages occupies the same situation he

did in the old establishment, and will probably

continue to occupy it as long as he lives. He has

no children of his own, but has put a little girl, a

relation of his, to school. Except in this instance,

and in the purchase of a few plain articles of furniture,

his freedom and his money seem not much

to have benefited him. A servant of mine, who

is intimate with him, thinks he is not as happy as

he was before his liberation. Several other servants

were freed at the same time, with smaller legacies,

but I do not know what has become of them.

I do not regard negro-slavery, however mitigated,

as a Utopian system, and have not intended so

to delineate it. But it exists, and the difficulty of

removing it is felt and acknowledged by all, save

the fanatics, who, like “fools, rush in where

angels dare not tread.” It is pleasing to know

that its burdens are not too heavy to be borne.

That the treatment of slaves in this state is humane,

and even indulgent, may be inferred from the

fact of their rapid increase and great longevity. I

believe that, constituted as they are, morally and

physically, they are as happy as any peasantry

in the world; and I venture to affirm, as the result

of my reading and inquiry, that in no country

are the laborers so liberally and invariably supplied

with bread and meat as are the negro slaves

of the United States. However great the dearth

of provisions, famine never reaches them.

P. S. — It might have been stated above that

on this estate there are about one hundred and

sixty blacks. With the exception of infants,

there has been, in eighteen months, but one

death that I remember, — that of a man fully sixty-five

years of age. The bill for medical attendance,

from the second day of last November, comprising

upwards of a year, is less than forty dollars.

The following accounts are taken from

“Ingraham’s Travels in the South-west,” a

work which seems to have been written as

much to show the beauties of slavery as

anything else. Speaking of the state of

things on some Southern plantations, he gives

the following pictures, which are presented

without note or comment:

The little candidates for “field honors” are useless

articles on a plantation during the first five

or six years of their existence. They are then to

take their first lesson in the elementary part of their

education. When they have learned their manual

alphabet tolerably well, they are placed in the

field to take a spell at cotton-picking. The first

day in the field is their proudest day. The young

negroes look forward to it with as much restlessness

and impatience as school-boys to a vacation.

Black children are not put to work so young as

many children of poor parents in the North. It

is often the case that the children of the domestic

servants become pets in the house, and the playmates

of the white children of the family. No

scene can be livelier or more interesting to a Northerner,

than that which the negro quarters of a

well-regulated plantation present on a Sabbath

morning, just before church-hours. In every

cabin the men are shaving and dressing; the women,

arrayed in their gay muslins, are arranging

their frizzly hair, — in which they take no little

pride, — or investigating the condition of their children;

the old people, neatly clothed, are quietly

conversing or smoking about the doors; and those

of the younger portion who are not undergoing the

infliction of the wash-tub are enjoying themselves

in the shade of the trees, or around some little

pond, with as much zest as though slavery and

freedom were synonymous terms. When all are

dressed, and the hour arrives for worship, they

lock up their cabins, and the whole population of

the little village proceeds to the chapel, where

divine service is performed, sometimes by an

officiating clergyman, and often by the planter

himself, if a church-member. The whole plantation

is also frequently formed into a Sabbath

class, which is instructed by the planter, or some

member of his family; and often, such is the

anxiety of the master that they should perfectly

understand what they are taught, — a hard matter

in the present state of their intellect, — that no

means calculated to advance their progress are

left untried. I was not long since shown a manuscript

catechism, drawn up with great care and

judgment by a distinguished planter, on a plan

admirably adapted to the comprehension of the

negroes.

It is now popular to treat slaves with kindness;

and those planters who are known to be inhumanly

rigorous to their slaves are scarcely countenanced

by the more intelligent and humane portion of

the community. Such instances, however, are

very rare; but there are unprincipled men everywhere,

who will give vent to their ill feelings and

bad passions, not with less good will upon the

back of an indented apprentice, than upon that of

a purchased slave. Private chapels are now introduced

upon most of the plantations of the

more wealthy, which are far from any church;

Sabbath-schools are instituted for the black children,

and Bible-classes for the parents, which are

superintended by the planter, a chaplain, or some

of the female members of the family.

Nor are planters indifferent to the comfort of

their gray-headed slaves. I have been much affected

at beholding many exhibitions of their

kindly feeling towards them. They always address

them in a mild and pleasant manner, as “Uncle,”

or “Aunty,” — titles as peculiar to the old

negro and negress as “boy” and “girl” to all

under forty years of age. Some old Africans are

allowed to spend their last years in their houses,

without doing any kind of labor; these, if not too

infirm, cultivate little patches of ground, on which

they raise a few vegetables, — for vegetables grow

nearly all the year round in this climate, — and

make a little money to purchase a few extra comforts.

They are also always receiving presents

from their masters and mistresses, and the negroes

on the estate, the latter of whom are extremely

desirous of seeing the old people comfortable. A

relation of the extra comforts which some planters

allow their slaves would hardly obtain credit at

the North. But you must recollect that Southern

planters are men, and men of feeling, generous

and high-minded, and possessing as much of

the “milk of human kindness” as the sons of

colder climes — although they may have been

educated to regard that as right which a different

education has led Northerners to consider

wrong.

With regard to the character of Mrs.

Shelby the writer must say a few words.

While travelling in Kentucky, a few years

since, some pious ladies expressed to her

the same sentiments with regard to slavery

which the reader has heard expressed by

Mrs. Shelby.

There are many whose natural sense of

justice cannot be made to tolerate the enormities

of the system, even though they hear

it defended by clergymen from the pulpit,

and see it countenanced by all that is most

honorable in rank and wealth.

A pious lady said to the author, with regard

to instructing her slaves, “I am

ashamed to teach them what is right; I

know that they know as well as I do that it

is wrong to hold them as slaves, and I am

ashamed to look them in the face.” Pointing

to an intelligent mulatto woman who

passed through the room, she continued,

“Now, there’s B—— . She is as intelligent

and capable as any white woman I

ever knew, and as well able to have her

liberty and take care of herself; and she

knows it isn’t right to keep her as we do,

and I know it too; and yet I cannot get my

husband to think as I do, or I should be

glad to set them free.”

A venerable friend of the writer, a lady

born and educated a slave-holder, used to

the writer the very words attributed to Mrs.

Shelby: — “I never thought it was right to

hold slaves. I always thought it was

wrong when I was a girl, and I thought so

still more when I came to join the church.”

An incident related by this friend of her

examination for the church shows in a

striking manner what a difference may often

exist between theoretical and practical benevolence.

A certain class of theologians in America

have advocated the doctrine of disinterested

benevolence with such zeal as to make

it an imperative article of belief that every

individual ought to be willing to endure everlasting

misery, if by doing so they could,

on the whole, produce a greater amount of

general good in the universe; and the inquiry

was sometimes made of candidates for

church-membership whether they could

bring themselves to this point, as a test of

their sincerity. The clergyman who was to

examine this lady was particularly interested

in these speculations. When he came to

inquire of her with regard to her views as

to the obligations of Christianity, she informed

him decidedly that she had brought

her mind to the point of emancipating all

her slaves, of whom she had a large number.

The clergyman seemed rather to consider

this as an excess of zeal, and recommended

that she should take time to reflect upon it.

He was, however, very urgent to know

whether, if it should appear for the greatest

good of the universe, she would be willing

to be damned. Entirely unaccustomed to

theological speculations, the good woman

answered, with some vehemence, that “she

was sure she was not;” adding, naturally

enough, that if that had been her purpose

she need not have come to join the church.

The good lady, however, was admitted, and

proved her devotion to the general good by

the more tangible method of setting all her

slaves at liberty, and carefully watching

over their education and interests after they

were liberated.

Mrs. Shelby is a fair type of the very

best class of Southern women; and while

the evils of the institution are felt and deplored,

and while the world looks with just

indignation on the national support and

patronage which is given to it, and on the

men who, knowing its nature, deliberately

make efforts to perpetuate and extend it, it

is but justice that it should bear in mind

the virtues of such persons.

Many of them, surrounded by circumstances

over which they can have no control,

perplexed by domestic cares of which

women in free states can have very little

conception, loaded down by duties and responsibilities

which wear upon the very

springs of life, still go on bravely and patiently

from day to day, doing all they can

to alleviate what they cannot prevent, and,

as far as the sphere of their own immediate

power extends, rescuing those who are dependent

upon them from the evils of the

system.

We read of Him who shall at last come

to judgment, that “His fan is in his hand,

and he will thoroughly purge his floor, and

gather his wheat into the garner.” Out

of the great abyss of national sin he will

rescue every grain of good and honest purpose

and intention. His eyes, which are as a

flame of fire, penetrate at once those intricate

mazes where human judgment is lost, and

will save and honor at last the truly good

and sincere, however they may have been

involved with the evil; and such souls as

have resisted the greatest temptations, and

persisted in good under the most perplexing

circumstances, are those of whom he has

written, “And they shall be mine, saith the

Lord of Hosts, in that day when I make up

my jewels; and I will spare them as a man

spareth his own son that serveth him.”

The character of George Harris has been

represented as overdrawn, both as respects

personal qualities and general intelligence.

It has been said, too, that so many afflictive

incidents happening to a slave are improbable,

and present a distorted view of the

institution.

In regard to person, it must be remembered

that the half-breeds often inherit, to a

great degree, the traits of their white ancestors.

For this there is abundant evidence

in the advertisements of the papers.

Witness the following from the Chattanooga

(Tenn.) Gazette, Oct. 5th, 1852:

Runaway from the subscriber, on the 25th

May, a VERY BRIGHT MULATTO BOY,

about 21 or 22 years old, named WASH.

Said boy, without close observation, might

pass himself for a white man, as he is very bright — has

sandy hair, blue eyes, and a fine set of

teeth. He is an excellent bricklayer; but I have

no idea that he will pursue his trade, for fear of

detection. Although he is like a white man in

appearance, he has the disposition of a negro, and

delights in comic songs and witty expressions.

He is an excellent house servant, very handy

about a hotel, — tall, slender, and has rather a

down look, especially when spoken to, and is

sometimes inclined to be sulky. I have no doubt

but he has been decoyed off by some scoundrel,

and I will give the above reward for the apprehension

of the boy and thief, if delivered at Chattanooga.

Or, I will give $200 for the boy alone;

or $100 if confined in any jail in the United States,

so that I can get him.

Chattanooga, June 15, 1852.

From the Capitolian Vis-a-vis, West

Baton Rouge, Louisiana, Nov. 1, 1852:

Runaway about the 15th of August last, Joe, a

yellow man; small, about 5 feet 8 or 9 inches

high, and about 20 years of age. Has a Roman

nose, was raised in New Orleans, and speaks

French and English. He was bought last winter

of Mr. Digges, Banks Arcade, New Orleans.

In regard to general intelligence, the

reader will recollect that the writer stated

it as a fact which she learned while on a

journey through Kentucky, that a young

colored man invented a machine for cleaning

hemp, like that alluded to in her

story.

Advertisements, also, occasionally propose

for sale artisans of different descriptions.

Slaves are often employed as pilots

for vessels, and highly valued for their skill

and knowledge. The following are advertisements

from recent newspapers.

From the South Carolinian (Columbia),

Dec. 4th, 1852:

VALUABLE NEGROES AT AUCTION.

BY J. & L. T. LEVIN.

WILL be sold, on MONDAY, the 6th day of December,

the following valuable NEGROES:

Andrew, 24 years of age, a bricklayer and plasterer,

and thorough workman.

George, 22 years of age, one of the best barbers

in the State.

James, 19 years of age, an excellent painter.

These boys were raised in Columbia, and are

exceptions to most of boys, and are sold for no

fault whatever.

The terms of sale are one-half cash, the balance

on a credit of six months, with interest, for notes

payable at bank, with two or more approved

endorsers.

Purchasers to pay for necessary papers.

November 27, 36.

From the same paper, of November 18th,

1852:

Will be sold at private sale, a LIKELY MAN,

boat hand, and good pilot; is well acquainted

with all the inlets between here and Savannah

and Georgetown.

With regard to the incidents of George

Harris’ life, that he may not be supposed a

purely exceptional case, we propose to offer

some parallel facts from the lives of slaves

of our personal acquaintance.

Lewis Clark is an acquaintance of the

writer. Soon after his escape from slavery,

he was received into the family of a sister-in-law

of the author, and there educated.

His conduct during this time was such as

to win for him uncommon affection and respect,

and the author has frequently heard

him spoken of in the highest terms by all

who knew him.

The gentleman in whose family he so

long resided says of him, in a recent letter

to the writer, “I would trust him, as the

saying is, with untold gold.”

Lewis is a quadroon, a fine-looking man,

with European features, hair slightly wavy,

and with an intelligent, agreeable expression

of countenance.

The reader is now desired to compare the

following incidents of his life, part of which

he related personally to the author, with

the incidents of the life of George Harris.

His mother was a handsome quadroon

woman, the daughter of her master, and

given by him in marriage to a free white

man, a Scotchman, with the express understanding

that she and her children were to

be free. This engagement, if made sincerely

at all, was never complied with. His

mother had nine children, and, on the death

of her husband, came back, with all these

children, as slaves in her father’s house.

A married daughter of the family, who

was the dread of the whole household, on

account of the violence of her temper, had

taken from the family, upon her marriage,

a young girl. By the violence of her

abuse she soon reduced the child to a state

of idiocy, and then came imperiously back

to her father’s establishment, declaring that

the child was good for nothing, and that

she would have another; and, as poor Lewis’

evil star would have it, fixed her eye upon

him.

To avoid one of her terrible outbreaks of

temper, the family offered up this boy as a

pacificatory sacrifice. The incident is thus

described by Lewis, in a published narrative:

Every boy was ordered in, to pass before this

female sorceress, that she might select a victim

for her unprovoked malice, and on whom to pour

the vials of her wrath for years. I was that unlucky

fellow. Mr. Campbell, my grandfather,

objected, because it would divide a family, and

offered her Moses; * * * but objections and

claims of every kind were swept away by the wild

passion and shrill-toned voice of Mrs. B. Me she

would have, and none else. Mr. Campbell went

out to hunt, and drive away bad thoughts; the

old lady became quiet, for she was sure none of

her blood run in my veins, and, if there was any

of her husband’s there, it was no fault of hers.

Slave-holding women are always revengeful toward

the children of slaves that have any of the blood

of their husbands in them. I was too young — only

seven years of age — to understand what

was going on. But my poor and affectionate

mother understood and appreciated it all. When

she left the kitchen of the mansion-house, where

she was employed as cook, and came home to her

own little cottage, the tear of anguish was in her

eye, and the image of sorrow upon every feature

of her face. She knew the female Nero whose

rod was now to be over me. That night sleep

departed from her eyes. With the youngest child

clasped firmly to her bosom, she spent the night

in walking the floor, coming ever and anon to lift

up the clothes and look at me and my poor brother,

who lay sleeping together. Sleeping, I said.

Brother slept, but not I. I saw my mother when

she first came to me, and I could not sleep. The

vision of that night — its deep, ineffaceable impression — is

now before my mind with all the

distinctness of yesterday. In the morning I was

put into the carriage with Mrs. B. and her children,

and my weary pilgrimage of suffering was

fairly begun.

Mrs. Banton is a character that can only

exist where the laws of the land clothe with

absolute power the coarsest, most brutal and

violent-tempered, equally with the most

generous and humane.

If irresponsible power is a trial to the

virtue of the most watchful and careful,

how fast must it develop cruelty in those

who are naturally violent and brutal!

This woman was united to a drunken

husband, of a temper equally ferocious. A

recital of all the physical torture which this

pair contrived to inflict on a hapless child,

some of which have left ineffaceable marks

on his person, would be too trying to humanity,

and we gladly draw a veil over it.

Some incidents, however, are presented

in the following extracts:

A very trivial offence was sufficient to call forth

a great burst of indignation from this woman of

ungoverned passions. In my simplicity, I put my

lips to the same vessel, and drank out of it, from

which her children were accustomed to drink.

She expressed her utter abhorrence of such an

act by throwing my head violently back, and

dashing into my face two dippers of water. The

shower of water was followed by a heavier shower

of kicks; but the words, bitter and cutting, that

followed, were like a storm of hail upon my young

heart. “She would teach me better manners than

that; she would let me know I was to be brought

up to her hand; she would have one slave that

knew his place; if I wanted water, go to the

spring, and not drink there in the house.” This

was new times for me; for some days I was completely

benumbed with my sorrow.

If there be one so lost to all feeling as even to

say that the slaves do not suffer when families

are separated, let such a one go to the ragged

quilt which was my couch and pillow, and stand

there night after night, for long, weary hours,

and see the bitter tears streaming down the face

of that more than orphan boy, while with half-suppressed

sighs and sobs he calls again and

again upon his absent mother.

“Say, wast thou conscious of the tears I shed?

Hovered thy spirit o’er thy sorrowing son?

Wretch even then! life’s journey just begun.”

He was employed till late at night in

spinning flax or rocking the baby, and