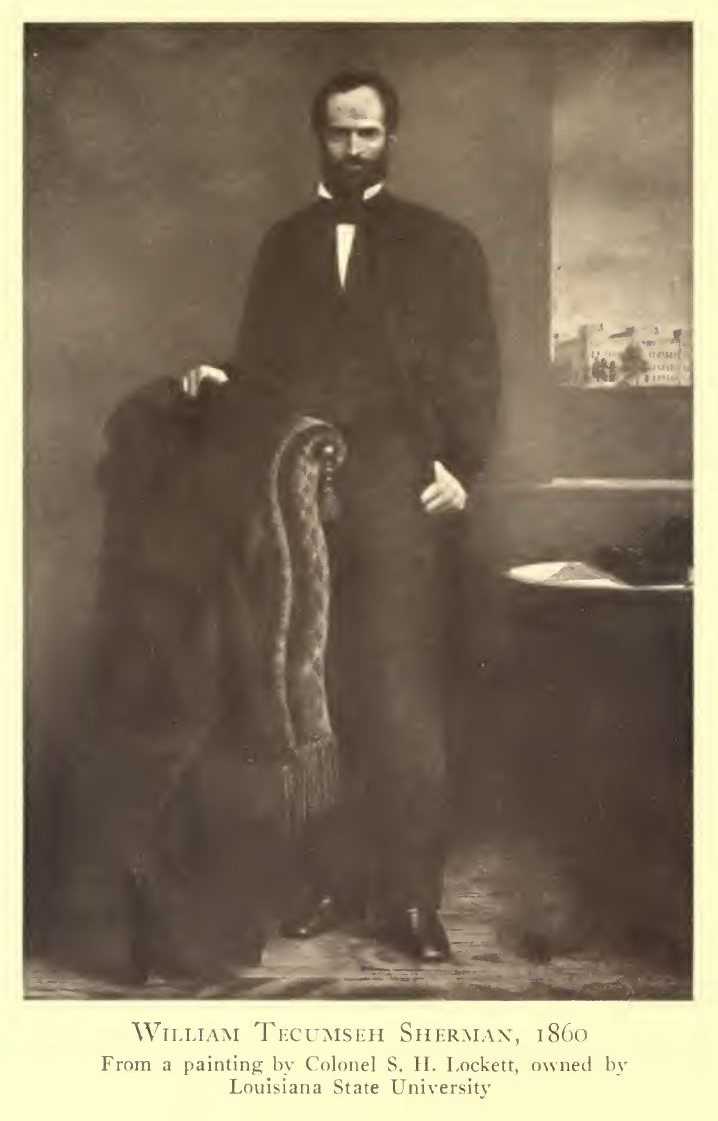

William Tecumseh Sherman.

General W. T. Sherman as College President.

CONTENTS

- Election Of The Seminary Faculty. Sherman Comes South

- Preparing For The Opening Of The Seminary

- The Beginning Of The First Session

- Student Troubles — Sherman Plans To Go To England

- The Reorganization Of The Seminary

- The Close Of The First Session

- The Vacation Of 1860: Ohio, Washington, New York

- The Second Session. The Coming Of Secession

- Secession — Superintendent Sherman Resigns

- To New Orleans And The North

ILLUSTRATIONS

- William Tecumseh Sherman, 1860

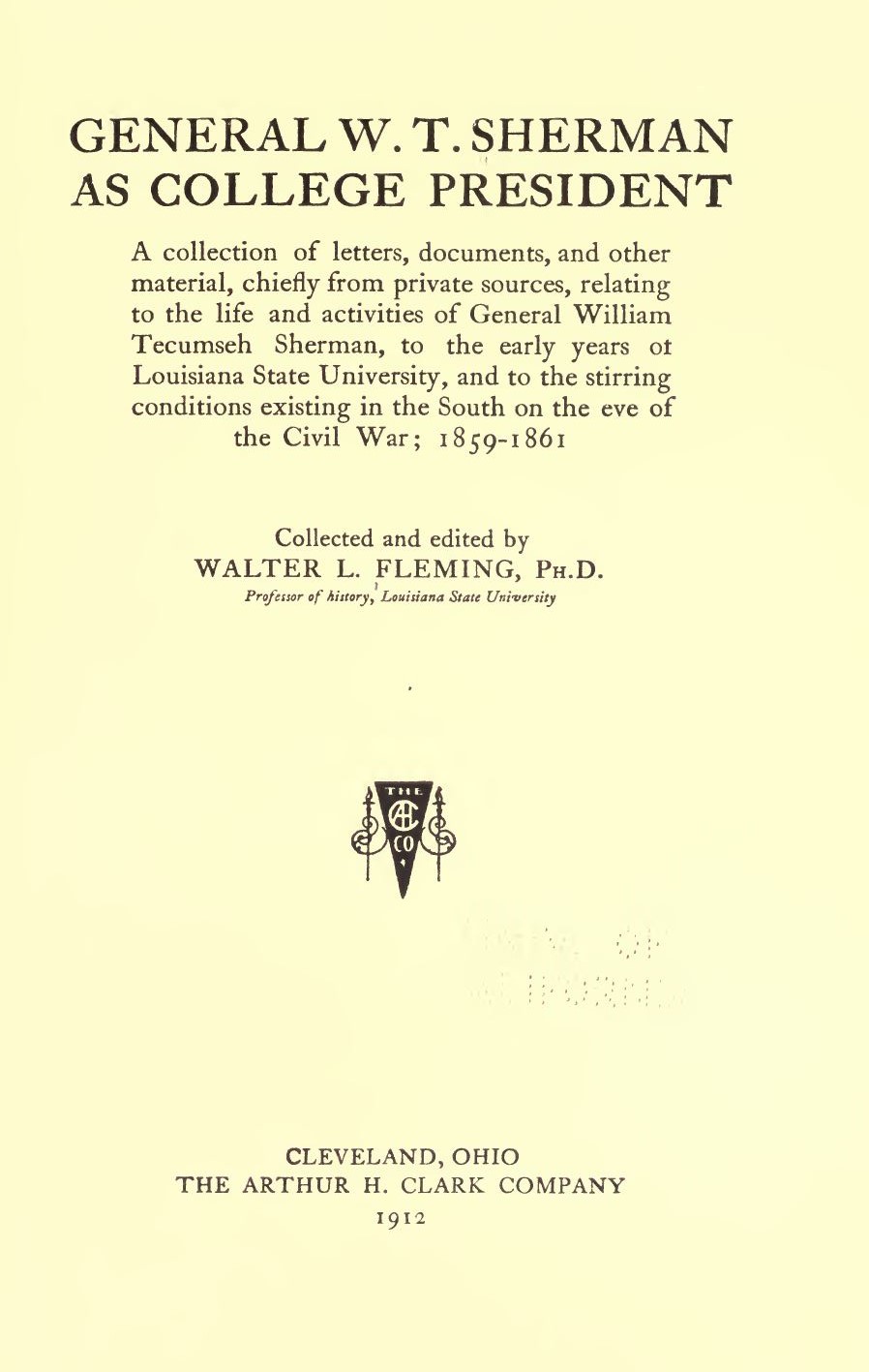

- The First Faculty:

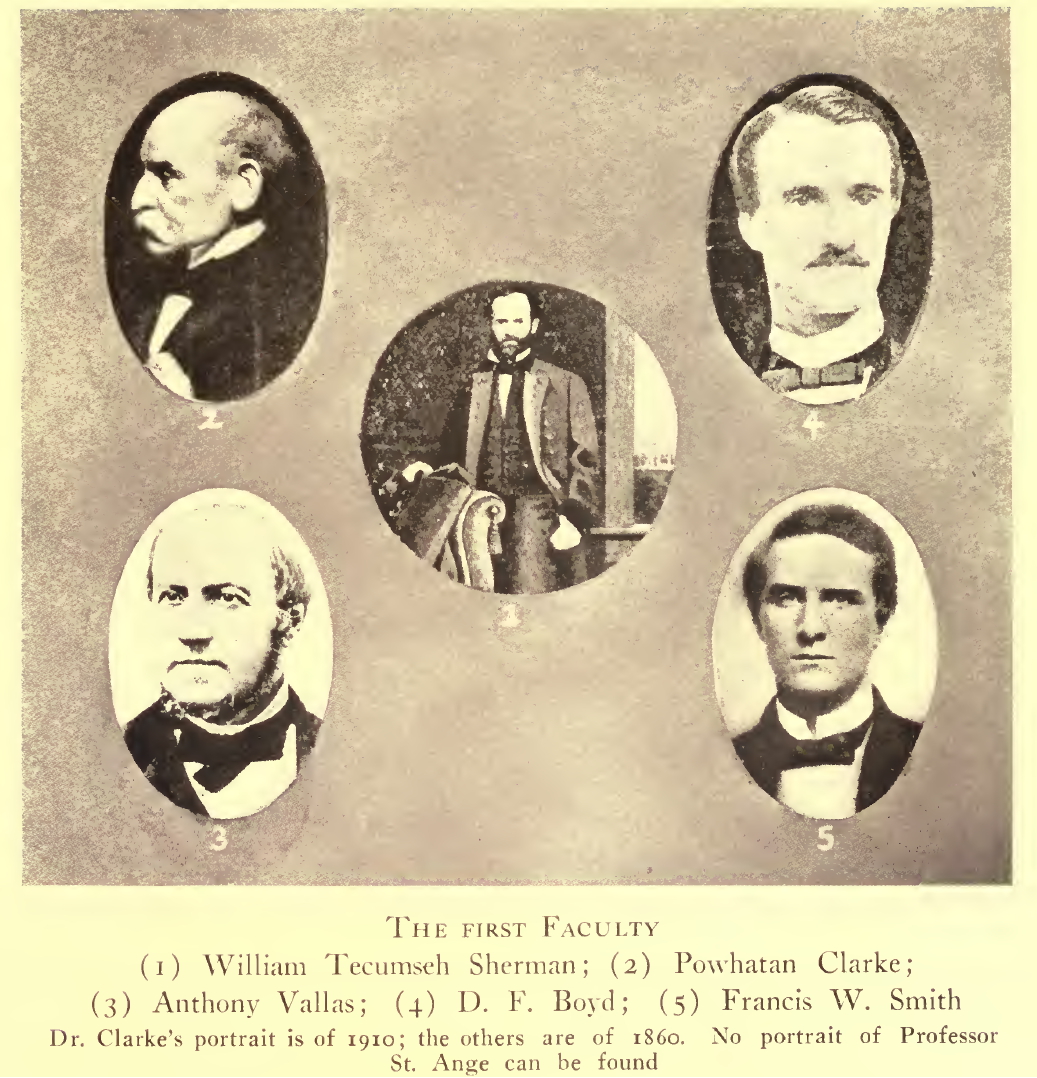

William Tecumseh Sherman, Powhatan Clarke, Anthony Vallas, D. F. Boyd, Francis W. Smith - Ground Floor Plan Of The Louisiana State Seminary

[Text Cut]

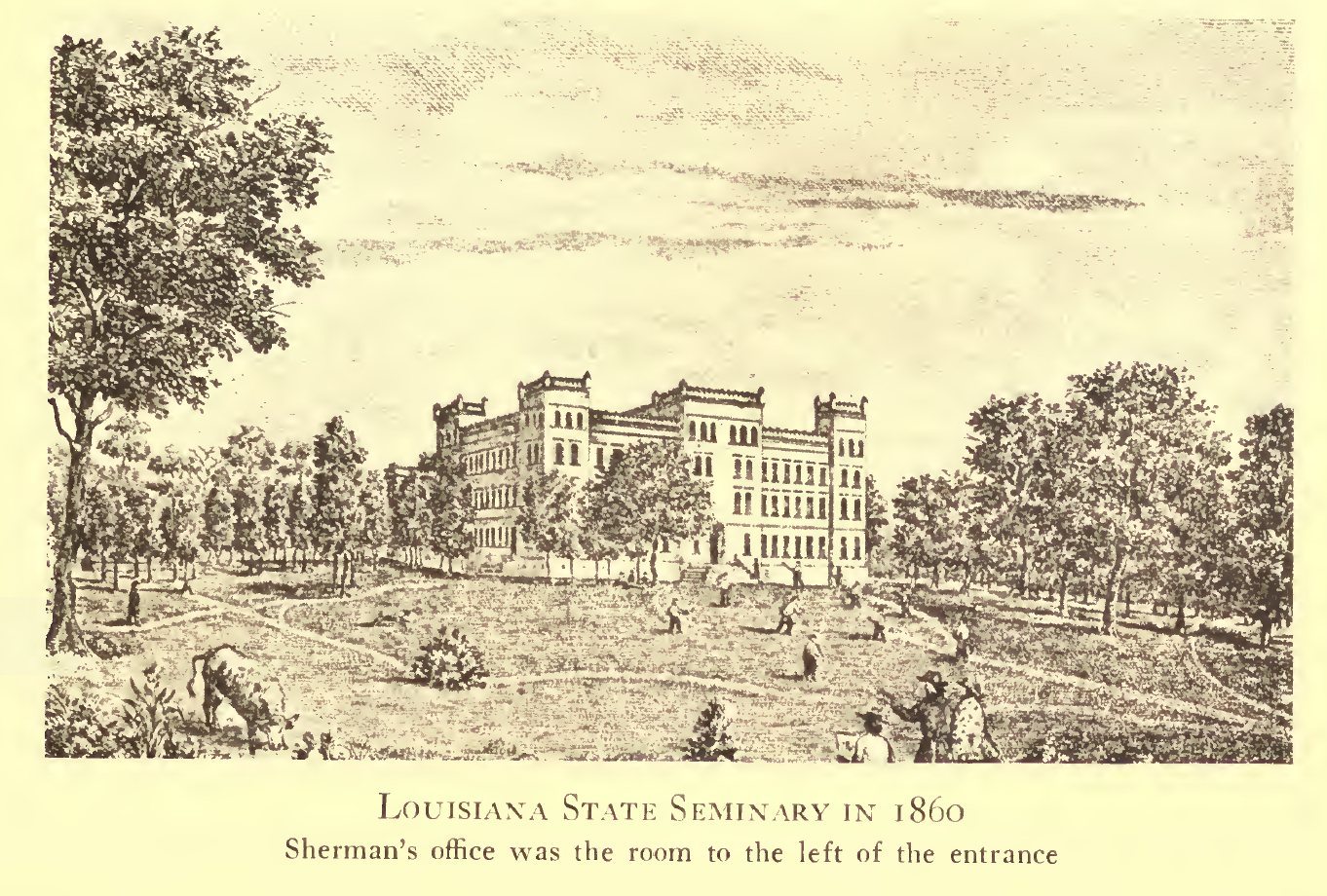

Drawn From Notes And Plan Accompanying General Graham's Letter To Sherman. - Louisiana State Seminary In 1860

LSU Ruins in 2013. - Letter Of Major P. G. T. Beauregard To Sherman (Three Plates)

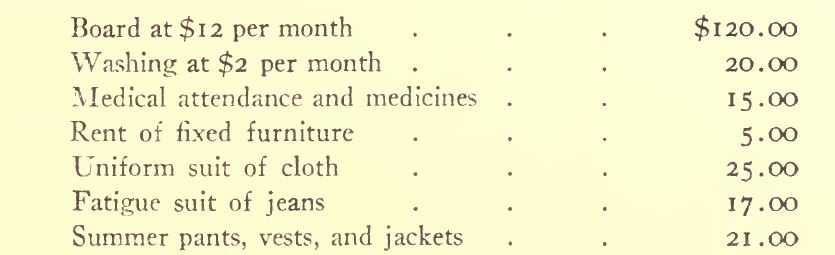

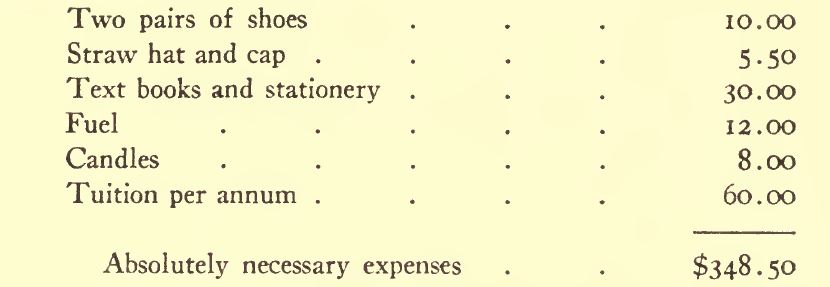

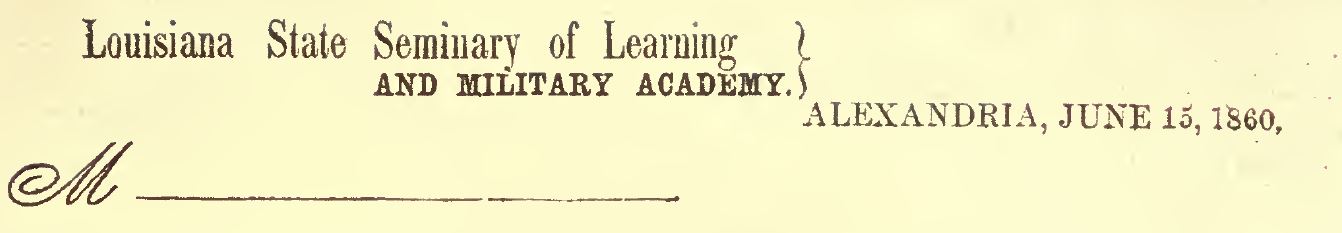

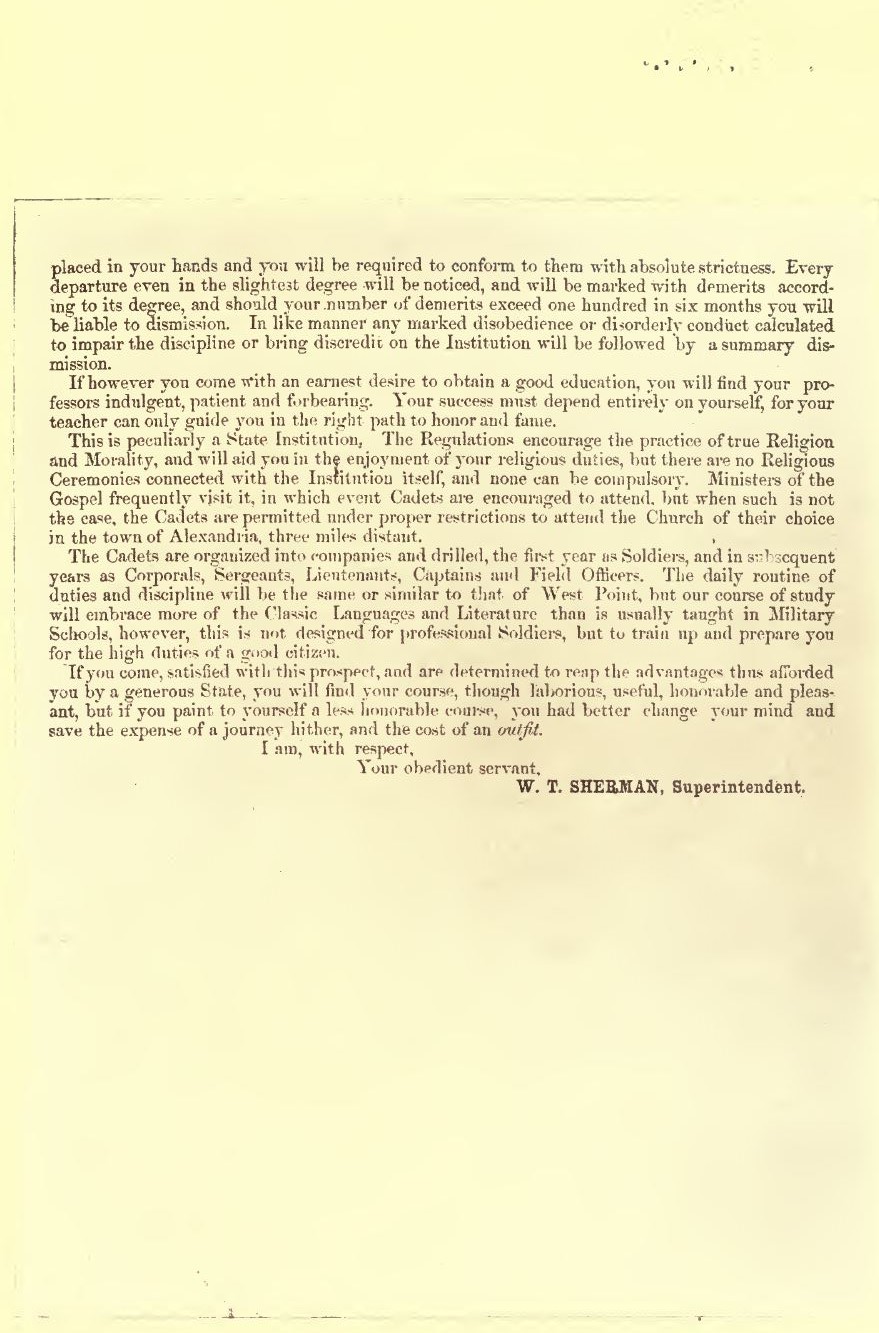

- Sherman’s Instructions To State Cadets (Two Plates)

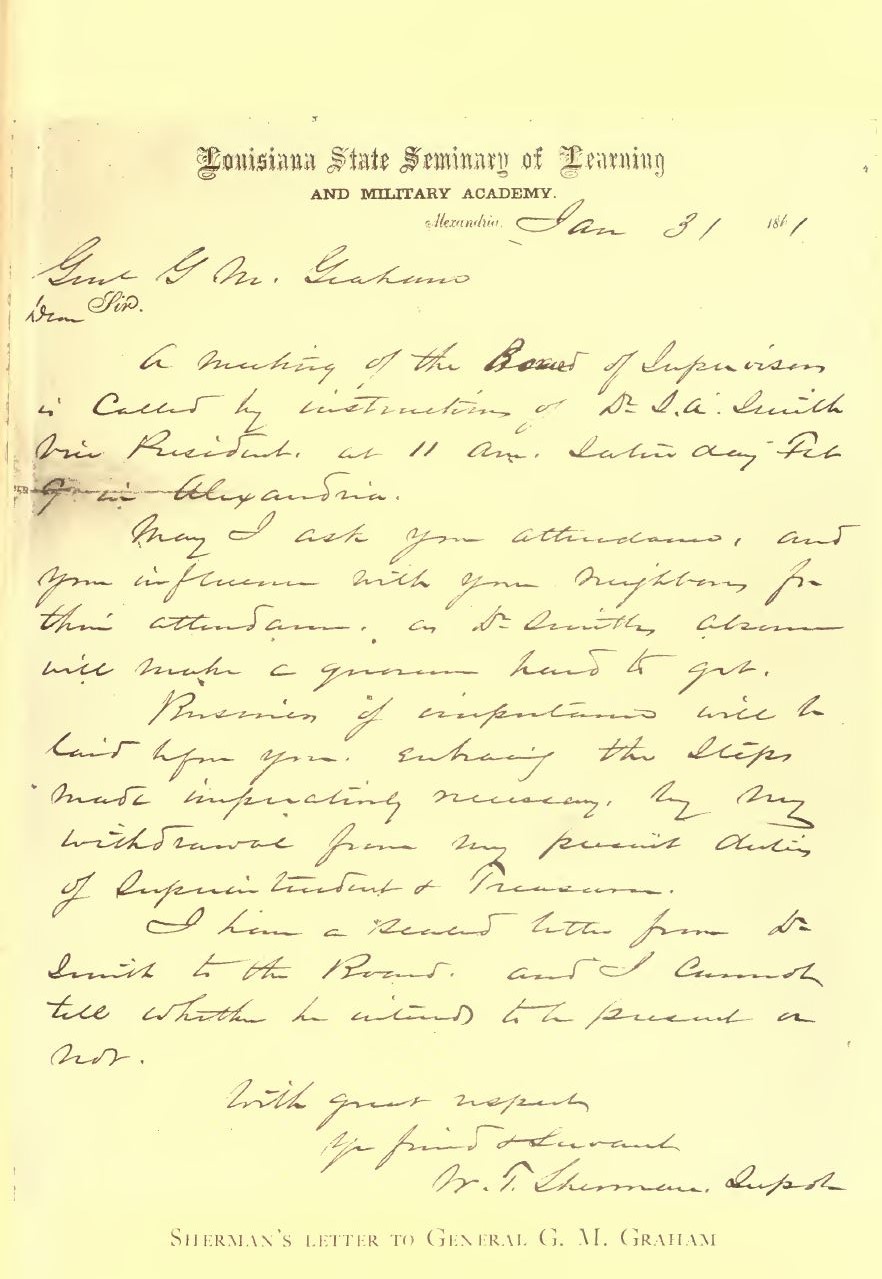

- Sherman’s Letter To General G. M. Graham

PREFACE

For assistance in gathering and preparing the material printed in this book I am indebted to the kindly services of many friends, especially to Philemon Tecumseh Sherman of New York City, who has permitted the use of all letters and documents in his possession relating to his father’s life in Louisiana; to Leroy S. Boyd, Esq., of Washington, D.C., who has turned over to me a mass of manuscript, pamphlet, and newspaper material relating to the early history of the Seminary; to President Thomas D. Boyd and Professors Albert M. Herget and William O. Scroggs, of Louisiana State University, who have given material assistance in the collection and preparation of the documentary material. My wife and her mother, Mrs. David F. Boyd, the widow of Sherman’s most intimate friend in Louisiana, and Miss Theo Jones, have assisted me greatly in verifying names and dates and in deciphering crabbed hand writing.

Walter L. Fleming.

Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, La.

August, 1911

INTRODUCTION

Purpose of the collection. Sherman’s plan for such a publication. His brief account of the organization of the Seminary. Sources of the material here reprinted. The organization of the Seminary.

The purpose of this work is to bring together upon the occasion of the semicentennial of the organization of Louisiana State University the material, chiefly documentary, relating to the beginnings of the Louisiana State Seminary (now the Louisiana State University) and to the life in Louisiana of William Tecumseh Sherman, the first executive of the institution. Late in life General Sherman planned such a collection and gathered material for it, but he did not publish it. In 1889 he wrote the following prefatory statement to a collection of letters and papers which with considerable additions are here published:

In Sherman’s Memoirs, published by the Appletons, volume i, pages 172-193, will be found a brief statement of the public events in Louisiana with which I was connected, and which immediately preceded the great Civil War. I now propose to supplement that statement by preparing in advance, not with any purpose of immediate publication, but rather for preservation in a convenient form, a series of letters which seem to me may become of value to posterity.

At a meeting of the Board of Supervisors of the Louisiana State Seminary of Learning, at Alexandria, Aug. 2, 1859, I was elected professor of engineering, architecture, and drawing and superintendent thereof. The action of the board was wholly the result of the recommendation of Major Don Carlos Buell, then in Washington, and of Gen. G. Mason Graham, half-brother to my old chief, Gen. [R. B.] Mason, in California.

This institution was designed to be a military college, and was located three miles north of Alexandria, a town of some importance on the south bank, and about a hundred miles up Red River. The funds for its maintenance were the proceeds of sales of public lands donated by the national Congress for this very purpose and held by the state in trust. The main building was already finished; was in every way suitable and appropriate and over the main entrance was inscribed: “By the liberality of the general government, the Union — Esto perpetua.”

The general control of this institution was committed to a Board of Supervisors, citizens of the State, of which the Governor was ex-officio the president.

Accordingly I first reported to Governor Wickliffe at Baton Rouge, the state capital, who informed me that the cares of his office engrossed his whole time, and that he wanted me to go on to Alexandria to confer with his successor, Governor-elect Thomas O. Moore, and to co-operate fully with Gen. G. Mason Graham, a member of the Board of Supervisors, who was in fact the real creator of the institution, and resided on his cotton plantation, “Tyrone,” nine miles above Alexandria, on the right or south bank of Red River (or its overflow channel, Bayou Rapides), whereas the Academy was on the left or north bank in the pine woods, on high and healthy ground.

I then proceeded to Alexandria by stage, stopping over night with Gov.-elect Moore on Bayou Robert, and then to Gen. Graham’s plantation, where we soon began the work of preparation. The professors had already been chosen at the same time with myself, and were within call.

Gen. Graham and I soon got to work agreeing perfectly that we should make a start on the 1st day of January, 1860 and should be ready to provide for and instruct about one hundred cadets. We had a limited amount of money, and everything had to be supplied in advance. A Mr. Jarreau was selected as steward. Tables, benches, blackboards, etc. had to be manufactured on the spot, and text books, bedding, and room furniture bought in New Orleans. Regulations had to be prepared and printed, circulars had to be prepared and circulated. All was accomplished and practical instruction was begun on the 1st of January, 1860.

The letters herewith will give a far better understanding of the private thoughts and feelings of the men who afterwards bore conspicuous parts in the Civil War than any naked narrative, and I merely intend this as a preface to them.

New York, Dec. 1, 1889.

W. T. S.

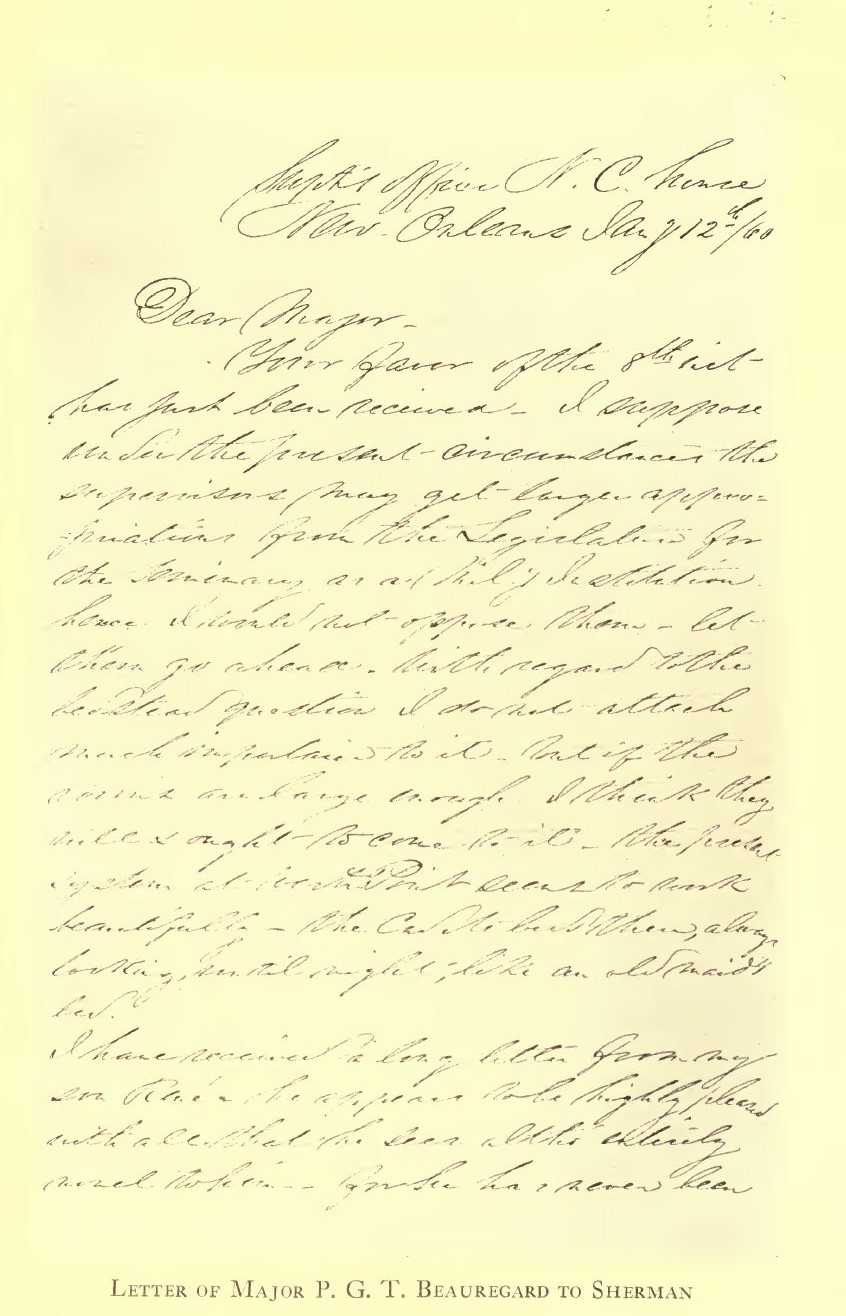

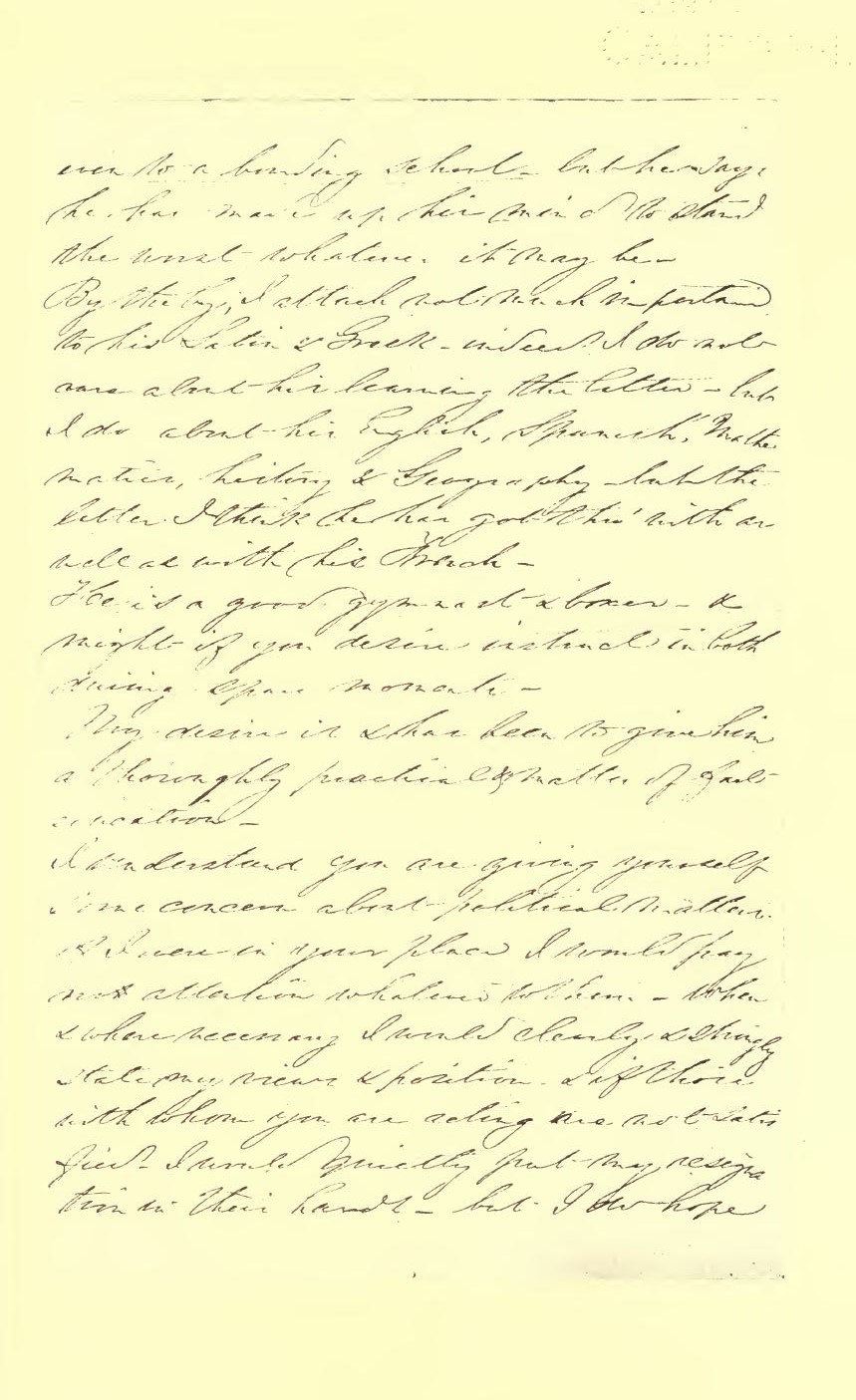

The collection here printed was gathered from various sources. It contains the letters collected by Sherman himself; other letters written by him or to him, and furnished to the editor by his son, P. T. Sherman, Esq.; a few extracts from Sherman’s Personal Memoirs which serve better than editorial matter to connect the letters; letters and documents from the archives of Louisiana State University; and correspondence relating to the Seminary from General G. Mason Graham, Major P. G. T. Beauregard, Captain George B. McClellan, Captain Braxton Bragg, Governors Wickliffe and Moore, and Dr. S. A. Smith.

These letters and documents will serve not only to show the beginnings of Louisiana State University, and Sherman’s part therein, as well as his views upon problems then agitating the nation, but they will throw light upon the social and political conditions of the time, and upon the feelings and actions of the southern leaders on the eve of the Civil War.

The Louisiana State Seminary (since 1870 called the Louisiana State University), which opened its doors on January 2, 1860, was the first institution of college grade in Louisiana to enjoy the undivided support of the state, and of the numerous colleges and universities, supported by the state, it alone has survived. It corresponds to the state universities of other states which were established on the foundation of Federal land-grants, but it was organized much later than the universities of states no older than Louisiana. This delay in establishing a state seminary or university was due to conditions within Louisiana: there was a lack of homogeneity in the population of French and Anglo-Americans — each with its distinctive ideals and religion; the educational system was decentralised and each geographic section, each church party, each nationality claimed its state-subsidized college.

This decentralized system was continued with some what unsatisfactory results until near the middle of the nineteenth century, when by the constitutions of 1845 and 1852 a state system of public schools was inaugurated and a single state supported “Seminary” authorized. The Seminary was to receive in addition to state appropriations the income from the sales of the public lands donated by the Federal government to the state of Louisiana in 1806, 1811, and 1827 “for the support of a seminary of learning.” These lands were not placed on the market until 1844. From 1845 to 1852 the legislature wrangled over the question of the location of the school. In the latter year it was decided to locate it near Alexandria in the Parish of Rapides; and in 1853 a site was selected three miles from Alexandria on the north side of the Red River. In 1859 the buildings were completed and a faculty selected.

The leader in all matters relating to the Seminary from 1845 to 1860 was General George Mason Graham, a Virginian, educated at West Point, and a veteran of the Mexican War. It was largely through his influence that William Tecumseh Sherman was elected superintendent of the State Seminary. Sherman, who was born in Ohio in 1820, was graduated from West Point in 1840, and after several years’ service in southern posts, was on staff service in California under General Roger

B. Mason, a half brother of General G. Mason Graham. He resigned from the army in 1853 and was for several years a banker in California and New York. At the time of his election he was practising law in Leavenworth, Kansas.

Walter L. Fleming.

I. ELECTION OF THE SEMINARY FACULTY SHERMAN COMES SOUTH

Meeting of the supervisors in May, 1859. The Seminary to be a literary and scientific institution under a military system of government. Advertisements for professors. Description of the building and grounds. D. C. Buell writes to Sherman about the Seminary. The election of a faculty for the Seminary. Graham’s account of the building and the professors. Sherman’s plans for the Seminary. Advice of Captain George B. McClellan relative to the organization of the Seminary. Sherman’s views on John Brown, slavery, and secession. Sherman arrives in Baton Rouge.

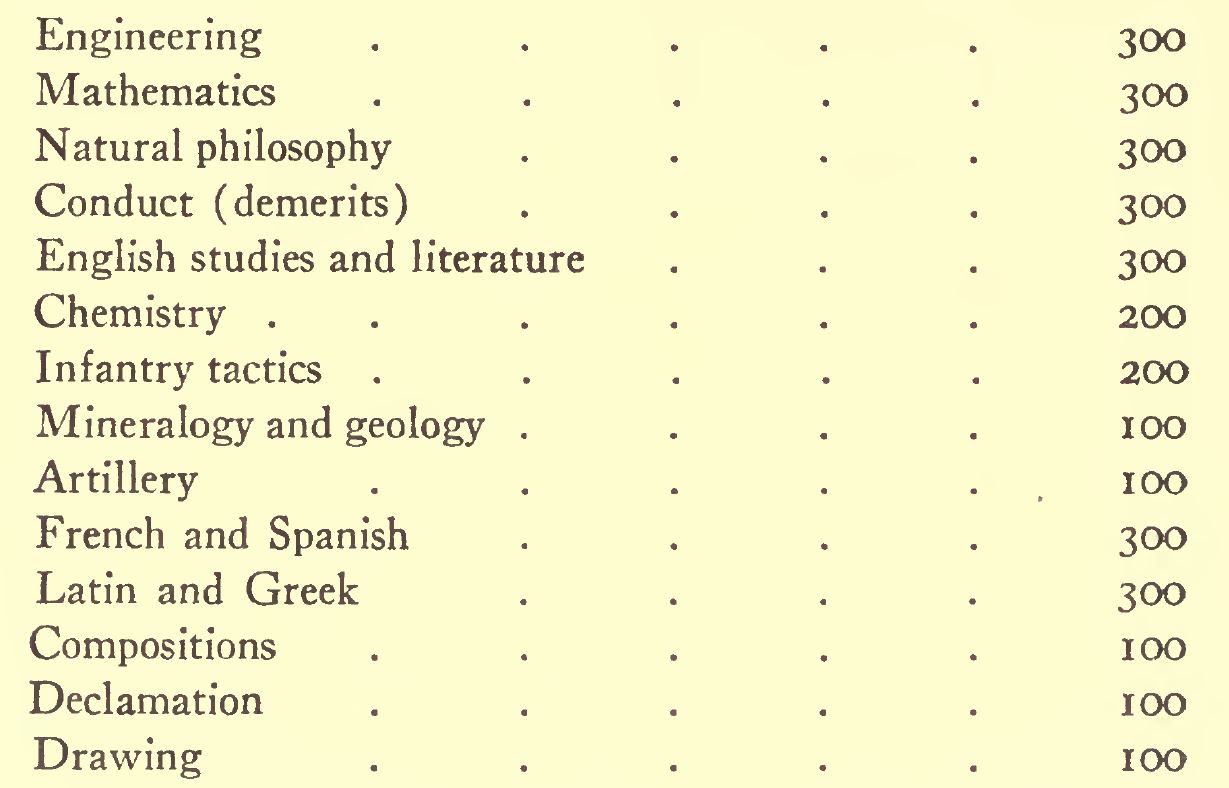

In May 1859 the Board of Supervisors of the State Seminary met at Alexandria and by a majority vote decided that the new college should be “a literary and scientific institution under a military system of government, on a program and plan similar to that of the Virginia Military Institute.” The several departments of instruction were established, and the salaries fixed. In order to secure the most competent professors Governor Wickliffe was asked to advertise for applications. The following statement, taken from the National Intelligencer, July 4, l859, Washington, D.C., was published widely over the South and the North.

Executive Office, Baton Rouge, La., May 10, 1859.

At a meeting of the Board of Supervisors of the State Seminary of Learning, held at Alexandria, in the Parish of Rapides, the following resolution was adopted:

Resolved, that the President of the Board, in his official capacity, advertise for applications from persons competent to fill:

- A professorship of mathematics, natural and experimental philosophy, with artillery tactics; to which office shall be attached a salary of twenty-five hundred dollars per annum — $2,500.

- The office of instructor of English and ancient languages; to which office shall be attached a salary of two thousand dollars per annum — $2,000.

- Instructor of engineering, architecture, and drawing; to which office shall be attached a salary of twenty-five hundred dollars — $2,500.

- The office of instructor of chemistry, geology, and mineralogy, and of infantry tactics; to which office shall be attached a salary of twenty-five hundred dollars per annum — $2,500.

- The office of instructor of the modern European languages; to which office shall be attached a salary of two thousand dollars per annum — $2,000.

From the five professors selected a superintendent will be chosen, who shall receive one thousand dollars — $1,000 — extra consideration in virtue thereof.

Furnished rooms to be provided to the professors free of charge.

In accordance with the foregoing resolution, notice is hereby given to all such persons as may desire to present themselves as competent to fill the chairs above enumerated, to make application, accompanied with recommendations, etc., to me, at the Executive Office at Baton Rouge, until the 15th day of July, and after that time at Alexandria, in the Parish of Rapides, until the ist day of August, 1859; at which time and place the selections will be made to fill the several professorships and a superintendent chosen.

The appointments thus made will take effect on the first Monday of January next (1860), at which time the institution will be opened.

The same issue of the National Intelligencer contained the following editorial written by General G. Mason Graham, vice-president of the Board of Supervisors.

In another column will be found the advertisement of Governor R. C. Wickliffe, president, ex-officio, of the Board of Supervisors of the Seminary of Learning of the State of Louisiana, inviting applications from persons competent to do so and desirous of filling the five chairs and the office of superintendent in that institution. . .

This institution, which is about to be organized as a scientific and literary institution, under a military system of government, on a programme and plan similar to that of the Virginia Military Institute at Lexington, in Virginia, is founded on a fund arising from the sales of land given by the general government many years ago to the Territory of Orleans for the establishment of a Seminary of Learning. The principal of this fund is, by the constitution of Louisiana, perpetually invested, at interest, in the hands of the state; the interest alone to be used in the establishment and maintenance of the school.

The really beautiful building for this institution, the main bodies of which are of three lofty stories, capped by a heavy cornice-wall finished in crennel work, and the five towers are of four stories, terminating in circular turrets, built on three sides of a quadrangle, one hundred and seventy feet front by one hundred and seventeen feet deep, with back buildings in reverse, so as to leave the fourth side of the area entirely open, is located in the open pine hills, where the trees have a growth of seventy-five feet and upwards to the branches, unobstructed by undergrowth, on a tract of four hundred acres owned by the institution; about three miles from the village of Pineville, on the north side of Red River opposite to the town of Alexandria, with which it is connected by a steam-ferry.

Alexandria — distant about thirty to thirty-five hours by steamboat from New Orleans — is a distributing post office, with a daily mail from New Orleans, and lines of four-horse post coaches running north, south, east, and west from it — contains a Catholic, an Episcopal, and a Methodist Church, the Episcopal Church having a chapel in Pineville.

Early in 1859 Sherman was a member of the law firm of Sherman, Ewing and McCook of Leavenworth, Kansas. Having decided to look for a more lucrative position, he wrote to the War Department asking about possible vacancies in the Pay Department. In reply Major D. C. Buell sent to him the advertisements given above, and the following letter.

Washington, D.C., June 17, 1859.

Dear Sherman: I received your letter this morning. It is unnecessary to make declarations when you already know so well that it would give me sincere pleasure to serve you. At present I see nothing of the kind you mention to suggest to you, but I will look about with hope that I may. There is no certainty of a vacancy in the Pay Department, though one of its members is now in serious difficulty about his account. If a vacancy should occur I know no reason why you should not endeavor to secure it, and succeed, too, if it were dependent on the merits which your case could be made to present.

You must remember, however, that in these times everything turns on political or other influence. If you can bring that kind of influence to bear on the President let it be done at once to secure a promise of the first vacancy; for it would be filled before I could even get the news to you by telegraph after it had occurred, so ready and pressing are the aspirants. . .

In the meantime, however, I enclose you a paper which presents an opening that I have been disposed to think well of. The only trouble is that the Academy has not yet been secured by state laws, though I think it al together probable that it will be. If you could secure one of the professorships and the superintendency, as I think you could, it would give the handsome salary of $3,500. The paper is sent to me by [George] Mason Graham, General [R. B.] Mason’s half-brother, and explains the whole matter. If you think well of it I have no doubt I can write him such a letter as will secure you a valuable advocate at first, and a useful supporter afterwards. You will observe there is not much time to spare. . .

[Endorsement by Sherman in 1889.] This was the first suggestion received by me on this subject, and to Gen. Buell I owe my election as superintendent of the Louisiana Seminary of Learning. He was seconded by Gen. G. Mason Graham, half-brother to my old chief in California, Col. R. B. Mason. Generals Bragg and Beauregard did not even know I was an applicant.

W. T. S.]

The advertisements attracted much attention and nearly a hundred applications for professorships were received. General Graham, vice-president of the Board of Supervisors, who was determined that a military man should head the school, had carried on a wide correspondence with a view to the selection of a suitable person. Having decided upon Sherman as best qualified for the superintendency he proceeded to use the press in his behalf. The following, from the Louisiana Democrat [Alexandria, La.] of July 20, 1859, is an editorial written by General Graham.

It is stated that Captain W. T. Sherman is one of the applicants for a professorship in our new State Seminary, and also for the position of the superintendency. He graduated at West Point in the class of 1840 and stood No. 6 on the merit roll. He was commissioned in the artillery and did his first service in California as adjutant-general for General R. B. Mason. He was brevetted for gallant and meritorious services and was subsequently appointed a captain in the general staff of the army. He resigned in ’53 to take control of the business of an extensive banking house in California which he managed with great skill. During his residence there he was made general of militia. Captain Sherman is spoken of as “standing high in the army as a scholar, soldier, and a gentleman — a man of great firmness and discretion and eminently remarkable for his executive and administrative qualities.”

From what we can hear there seems to be no room to fear an insufficient number of applicants for professor ships in the Seminary. The greater the list the better enabled will the Board of Supervisors be to make a good selection. It is to be hoped that the reputation, learning and ability of the corps of professors will be such as to render our new Seminary one of the fore most institutions of the South.

The supervisors, on August 2, 1859, proceeded to the election of the first faculty of the Seminary. The Louisiana Democrat of August 3 gives this account of the proceedings.

Agreeably to adjournment the Board of Supervisors of the Louisiana State Seminary met on Monday, Aug. ist. His Excellency, Governor Wickliffe, president ex officio of the Board, presided. The members in attendance were T. C. Manning, Esq., Gen. G. Mason Graham, Col. Walter O. Winn, S. W. Henarie, Esq., Hon. M. Ryan, Hon. P. F. Keary, Hon. J. A. Bynum, Hon. W. W. Whittington, Hon. W. L. Sanford, Col. Fenelon Cannon.

The principal business before the Board was the selection of a superintendent and a corps of professors for the Seminary. Some idea of the difficulty of their task may be formed from the fact that there were forty applicants for the chair of ancient languages, twenty for that of mathematics, nine for that of modern languages, nine for that of chemistry and mineralogy, and three for that of engineering.

These applicants were from all sections, Maine, New Hampshire, the northwest, Kentucky, Virginia, Georgia; and even graduates of European universities were among the candidates. One enterprising person, a Mr. Goodwyn, Ichabod Goodwyn, was candid enough to acknowledge himself a “republican” (“Black Republican” in politics, but trusted that the little circumstance would make no difference!) Mr. G. will have his name registered in the list of unsuccessful candidates. The Board would have admired his candor if they had not been astonished at his impudence. Mr. G. would be a splendid superintendent of a brass button manufactory. Teachers enough for the young men of Louisiana can be found without employing any of Greeley’s brazen faced disciples. We shall refer to Mr. Goodwyn’s application again hereafter.

After full examinations of certificates, the Board made choice of the following:

Major W. T. Sherman, superintendent, and professor of engineering, architecture, and drawing; Anthony Vallas, PH.D., professor of mathematics and of natural and experimental philosophy; Francis W. Smith, A.M., professor of chemistry and mineralogy; E. Berte St Ange, professor of modern languages; D. F. Boyd, A.M., professor of ancient languages.

Of Major Sherman’s qualifications, we have spoken in a recent issue. Dr. Vallas, is a graduate of the University of Pesth, Hungary, in which institution he has filled with distinction a professor’s chair. He is the author of several scientific and mathematical works held in high estimation. Mr. Smith is a graduate of the Virginia University, and also of the Military Institute of that state. Mr. St. Ange, is a native of France, and has served with distinction as an officer in the French navy. He has taught in the University of Louisiana, and for some time also in this Parish. Being known to most members of this Board as a thorough instructor his election was unanimous. Mr. Boyd is a graduate of the University of Virginia, and like the rest highly recommended for proficiency and talent.

The traditional account of Sherman’s election was written down nearly forty years later by D. F. Boyd from whose manuscript the paragraphs given below are taken.

[Sherman’s] application for position in the Military Academy was characteristic of him. When Governor Wickliffe and the Board of Supervisors met on the hot, sultry summer day in 1859, to make the faculty appointments, there were many applications; and after they had waded through a mass of testimonials — flattering words of loving, partial friends, genealogies, etc. — such hand some nothings as only enthusiastic southerners can say of each other, and of their ancestors for generations back, when an office is in sight, a half-sheet letter was opened and read about to this effect:

Governor Wickliffe, president, Board of Supervisors.

Sir: Having been informed that you wish a superintendent and professor of engineering in the Military Academy of Louisiana, soon to be opened, I beg leave to offer myself for the position.

I send no testimonials. . . I will only say that I am a graduate of West Point and ex-army officer; and if you care to know further about me, I refer you to the officers of the army from General Scott down, and in your own state to Col. Braxton Bragg, Major G. T. Beauregard, and Richard Taylor, Esq. Yours respectfully,

W. T. Sherman.

(1) William Tecumseh Sherman; (2) Powhatan Clarke; (3) Anthony Vallas; (4) D. F. Boyd; (5) Francis W. Smith

Dr. Clarke’s portrait is of 1910; the others are of 1860. No portrait of Professor St. Ange can be found

No sooner was this letter read, than Sam. Henarie, a plain business man and member of the Board, exclaimed: “By G—d, he’s my man. He’s a man of sense. I’m ready for the vote!” “But,” said Governor Wickliffe, “we have a number more of applications. We must read them all.” “Well, you can read them,” rejoined Henarie, “but let me out of here, while you are reading. When you get through, call me, and I’ll come back and vote for Sherman.” Sam heard no more “testimonials.” Sherman was elected. . .

To the successful applicants for positions the governor sent formal notices of appointment while General Graham entered into a lengthy correspondence with the newly elected superintendent in regard to the work that was still to be done before opening. Typical letters are here selected.

GOVERNOR ROBERT C. WICKLIFFE TO W. T. SHERMAN

Executive Office, Baton Rouge, La., Aug. 5,1859.

Sir: I have the pleasure to inform you that at a meeting of the Board of Supervisors of the Seminary of Learning, held at Alexandria on the 1st of August, you were elected to fill the chair of professor of engineering, architecture, drawing, etc., and as superintendent of the institution.

You will please inform me at what time, between this and the first of December, it will be convenient for you to meet a committee of the Board of Supervisors, to make necessary arrangements for the organization of the institution.

G. MASON GRAHAM TO W. T. SHERMAN

Steamboat Minnesota, descending Red River, La.,

August 3, 1859

Sir: I have the gratification to inform you, in advance probably of your official notification by Gov.

Wickliffe, that the Board of Supervisors of the Seminary of Learning, State of Louisiana, yesterday elected you to the chair of engineering, architecture, and drawing in that institution, and to the post of superintendent thereof. . .

I am now en route to join my family at Beer-Sheba Springs, Tennessee, where I shall remain until the last days of August and thence to Washington City all the month of September. My address there will be to “care Richard Smith, Esq., cashier, Bank of the Metropolis.” Hope to be at home by first of November, where from the 1st to the loth, shall be glad if you can join me, making the headquarters of your family at my house, where we have abundant room, but are nine miles distant from Alexandria, thirteen from the Seminary.

If entirely convenient and comfortable to your family, however, to remain behind, it would be wisest for you to come down alone at first, as there are no residences yet provided, and you will all have to quarter at first in the building. Yourself and Dr. Vallas are the only two married men on the Academic Board, and the Board of Supervisors has taken the initiatory for the creation of two dwellings, but it requires the authorization of the legislature, which assembles on the 3rd Monday in January.

It will be necessary for you to be here as soon as possible after my own return, as the preparation for, and the starting of, the whole machinery has been devolved mostly on you and myself, including the furnishments of the building, as you will see from the published accounts of our proceedings which will be forwarded to you (apropos: the statement in the governor’s advertisement that “furnished apartments will be provided the professors in the building” was an error of our secretary’s. It should have read “Apartments will be furnished the professors in the building free of charge therefor” le meublant of them however to be left to themselves).

I enclose to your address at Leavenworth, to be mailed with this in New Orleans, a packet containing four publications from the Virginia Military Institute, one of them a copy of its “Rules and Regulations,” so that in devoting in advance, what leisure moments you may have to the preparation of your plans, you may have the experience of our model before you.

If an article in the Daily National Intelligencer of Monday, July 4th, headed “Louisiana Seminary” met your eye, you will have gathered from it a pretty exact idea of its locale. A little ground plan which I have endeavored to make amidst the tremulous motion of the boat, and enclose here, will enable you to form some idea of the capacity of the Building.

Doctor Vallas is an Episcopal clergyman (which quality he sinks entirely, that is, in the exercise of it, so far as the institution is concerned), an Hungarian, an accomplished gentleman, an erudite scholar, a profound and practised mathematician and doctor of philosophy. Has occupied various chairs in the colleges of Vienna and at the time of the establishment of the Revolutionary Government in Hungary, was professor of mathematics in the University at Pesth, in which capacity he was ordered by that Government to organize a military department to the University in which he superintended the instruction of about five hundred young men for two years, when the Austrians recovering possession of Pesth he was dismissed from the Military school and was himself court-martialed. Saving his head, they only removed his body from the office of professor of the university, and altho’ there is satisfactory evidence that he might have been restored to that position, he preferred a voluntary expatriation. He resides in New Orleans, readily at hand.

Monsieur St. Ange seems to be a gentleman and well educated scholar — has served in the Marine Corps of France. Is in Alexandria.

David F. Boyd, an eleve of the University of Virginia and native of that state, is now teacher in a school in the northerly part of Louisiana. He, too, is therefore readily at hand.

Francis W. Smith, native of Virginia andeleve of its military institute, is a very young man, a nephew of both Col. Smith, the superintendent, and of Major Williamson, one of the professors in the V.M.I. He comes strenuously recommended as eminently qualified to fill any chair in our school, except that of modern languages, being only a French scholar. Is now at Lexington, Virginia or Norfolk, where his family reside.

In concluding this long, and to me wearying paper, I beg to say to you that much is expected of you — that a great deal will devolve upon you, and to add that at our Board dinner yesterday, Governor Wickliffe with great cordiality and kind feeling proposed your health and success, and that it was responded to by the other members in brimming glasses.

P.S. If you know Mr. and Mrs. A. I. Isaacs, now I think residing in Leavenworth, they can tell you all about our country here.

W. T. SHERMAN TO G. MASON GRAHAM

Lancaster, O., Aug. 20, 1859.

Dear Sir: I wrote you a few days ago, in part answer to your very kind note addressed me at Lancaster. I am now in possession of your more full letter sent by way of Leavenworth, and shall receive to-day the printed reports to which you referred.

These will in great measure answer the manifold questions propounded by me. When in full possession of these I will again write you, and when I know you are at Washington, I may come there to meet you, and to make those preliminary arrangements as to furnishing the building, selecting text books, etc., all of which will no doubt have to be approved by the Board of Education in Louisiana.

I can easily secure from West Point the most complete information on all the details of the management and economy of that institution. Then, being in possession of similar data from the Virginia Institution, we can easily lay a simple foundation, on which to erect, as time progresses, a practical system of physical and mental education, adapted to the circumstances of Louisiana. I shall not take my family south this winter, and shall hold myself prepared to meet you at Alexandria, or elsewhere, at the earliest date you think best. I feel deeply moved by your friendly interest in me, and both socially and in the new field hereby opened to me I will endeavor to reciprocate your personal interest and justify your choice of a superintendent.

I have seen a good deal of the practical world, and have acquired considerable knowledge, but it may be desultory, and may require some time to reduce it to system, and therefore I feel inclined to see the Board of Education select a good series of practical books as textbooks.

If this has already been done, I will be the better pleased; if this devolve on the professors it will require some judgment to adjust them, lest each professor should attempt too much, and give preference to text books not intimately connected with the other classes. The adjustment of the course of studies, the selection of the kind and distribution of physical, muscular education, and how far instruction in infantry, sword and even artillery practice shall be introduced are all important points, but fortunately we have a wide field of choice, and the benefit of the experience of others. As soon as I learn you are in Washington, and as soon as I know all that has been done, I will give my thoughts and action to provide in advance the knowledge out of which the Board of Education may choose the remainder.

G. MASON GRAHAM TO W. T. SHERMAN

Willard’s Hotel, Washington, Sept. 7, 1859.

Dear Sir: On arriving here night before last I had the pleasure to receive from Mr. Richard Smith your two favors of the 15th and 20th of August, and Major Buell, with whom I have not been able to meet until this morning at breakfast, has shown me yours to him of the 4th inst. which he was in the act of opening when I joined him, and from which he has allowed me to take a memorandum of the dates of your proposed movements. The information contained in your letter to Buell has been of considerable relief to me, for whilst it would be very gratifying to me to meet with you I did not see any good commensurate with the expense, time, risk, and trouble to yourself, to result from your coming all the way here merely to confer with me when it was not in my power to specify any particular day when I would be in the city, as the business which brings me here lies down in Virginia, whither I go tomorrow morning, if the violent cold under which I am now suffering shall permit, and the consummation of it is contingent on the action of a half dozen others than myself.

I had desired very much, if it suited your convenience, that you could visit and see into the interior life of the school at Lexington, Virginia, where everything would be shown to you with the most cordial frankness by Col. Smith, who has taken the warmest and most earnest interest in our effort, and who writes to me of you, sir, in very high terms of congratulatory appreciation, and where one of your classmates, Major Gilham, is a member of the Academic Board.

In the event that this will not be practicable to you, as I infer from the programme laid down in your note to Major Buell it will not be, I shall write to Col. Smith asking him to give us all necessary information of details not contained in the “Rules and Regulations” the preparation of the code of which for our school is confined to the joint action of “the faculty” and “A Committee consisting of Messrs. Manning, Graham, and Whittington.” I would rather have had the Board adopt for the present the code of the Virginia school, because under the Governor’s resolution, about which he did not confer with me beforehand, it cannot well be done until on or about the 1st of January, when it ought to be done in advance. I do not see therefore that we can do otherwise than adopt, at first, the code of that school. I have no apprehension but that whatever you, Mr. Manning and myself may agree upon, will be acceptable to all the rest.

In regard to “furnishing” the building there will not be much trouble. My idea will be for each cadet to furnish his own requisites in the way of room furniture, as at West Point. There will then be nothing to furnish but the class-rooms, the kitchen and mess hall — as I believe I mentioned to you before, the statement in the Governor’s advertisement that “furnished apartments would be provided in the building for the professors,” was an error of our not very clear-headed secretary. The intention of the Board was simply to apprize all interested that there were no separate dwellings for the professors. . .

I met with Mr. F. W. Smith in Richmond and travelled with him to this place. He is about sailing for Europe to be back the 1st of December. All my anticipations of him fully realized. I cannot close without mentioning that in a visit to the convent in Georgetown yesterday my sister (Mary Bernard) poured out her joy on learning (to do which she en quired with great eagerness) that the superintendent of our school was the husband of that “one of all the girls who have passed through our hands here that I believed I loved best and was the most deeply interested in.”

In regard to “authority and control,” although it is not yet exactly so, I hope the next session of the legislature will place our school on precisely the same footing as the Virginia school, making the superintendent the commanding officer of the corps of cadets, giving to him and the other members of the Academic Board, rank in the State’s military organization.

W. T. SHERMAN TO G. MASON GRAHAM

Lancaster, Ohio, Sept. 7, 1859.

Dear Sir: I am now in full possession of all documents sent to my address at Leavenworth including the papers containing the printed proceedings of the Board of Supervisors of August 2. I have written to you twice at Washington, but suppose you are not well arrived, and as I find it best somewhat to qualify my offer to come East, and visit with you the Virginia Institute, I write you again.

I have written Governor Wickliffe that I will be at Saint Louis, Oct. 20 and at Baton Rouge Nov. 5, prepared to meet the committee of supervisors, or the academic faculty at any time thereafter he may appoint. But it may be more convenient for that committee to meet at once in Alexandria or at the institute [Seminary] itself, so that I can be there at any date after Nov. 5, which may prove agreeable to all parties.

To-morrow I will go to Frankfort, Kentucky, to be present at the opening of the session of the Kentucky Military Institute and I will remain long enough to see for myself as much of the practical workings of that institute as possible. Colonel Morgan in charge will, I know, take pleasure in making me acquainted with all details that I may desire to learn.

From Kentucky I shall return to this place, and about the 25th inst. I will go to Chicago, where I expect to meet Captain McClellan of the Illinois Central Railroad, who a few years since visited many of the European establishments, and who can therefore give me much information. I will then go to Leavenport and afterward St. Louis delaying at each point a short while, but you may rest perfectly certain that I will be on hand, when the committee meets and that I will acquire as much practical knowledge of organization as possible in the meantime.

I hope you will find it both pleasant and convenient to visit the Virginia Military Institute and that you will make inquiries that will be of service — thus ascertain the exact price of each article of dress, and furniture furnished the cadets, price of each text-book — how supplied, cost of black-board, drawing-board, mathematical instruments, drawing-paper, paints, pencils, etc. The name of the merchant who supplied them. Have they a single store, like an army suttler who keeps supplies on hand, and whose prices are fixed by the Academic Board, or does their quartermaster provide by wholesale and distribute to cadets charging them? Are all cadets marched to mess hall? Do they have regular reveille, tattoo and taps?

Can we not select a dress more becoming, quite as economical, and better adapted to climate than the grey cloth of West Point and Virginia?

It occurs to me that climate will make it almost necessary to make modifications of dress, period of study, drill, and even dates of examinations. This may all be done without in the least impairing that systematic discipline which I suppose it is the purpose to engraft on the usual course of scientific education.

Ascertain if possible, the average annual expense of each cadet — clothing, mess hall, books, paper, etc., lights fire, and washing and tuition.

I will try and ascertain similar elements in Kentucky and elsewhere, so that we may begin with full knowledge of the experience of all others. Should you write me here the letters will be so forwarded as to meet me with as little delay as possible.

Sherman’s views on slavery, politics, etc., were moderate. Had he taken an active part in public affairs he would probably have been an Old Line Whig. His brother John was already noted as an anti-slavery Republican. Just before leaving for Louisiana Major Sherman wrote to his brother urging him to take a moderate position on sectional questions.

W. T. SHERMAN TO JOHN SHERMAN

Lancaster, Ohio, Sept., 1859.

I will come up about the 2Oth or 25th, and if you have an appointment to speak about that time, I should like to hear you, and will so arrange. As you are becoming a man of note and are a Republican, and as I go south among gentlemen who have always owned slaves, and probably always will and must, and whose feelings may pervert every public expression of yours, putting me in a false position to them as my patrons, friends, and associates, and you as my brother, I would like to see you take the highest ground consistent with your party creed. . .

October, 1859.

Each State has a perfect right to have its own local policy, and a majority in Congress has an absolute right to govern the whole country; but the North, being so strong in every sense of the term, can well afford to be generous, even to making reasonable concessions to the weakness and prejudices of the South. If southern representatives will thrust slavery into every local question, they must expect the consequences and be out voted; but the union of states and general union of sentiment throughout all our nation are so important to the honor and glory of the confederacy that I would like to see your position yet more moderate.

During the summer while at Lancaster, Sherman wrote to several officers of the army with whom he had been associated, asking for their views on certain problems of military school organization. The following letter from Captain George B. McClellan is the only one that has been preserved. It was taken from the Seminary in 1864 by an officer of Gen. Banks’s army and was returned to Louisiana State University in 1909. It bears the following endorsement by Sherman: “Capt. McC. went to Sebastopol and reported to our government. He spent more than a year in Austrian, Russian, and English camps and is a gentleman of singular intelligence.”

GEORGE B. McCLELLAN TO W. T. SHERMAN

Illinois Central Railroad Company,

Vice President’s Office, Chicago,

Oct. 23, 1859.

My Dear Sir: I regret exceedingly that I have so long delayed replying to yours of the 30th, ult. I hope this will reach you at Baton Rouge in time to serve your purposes, and must beg you to consider my rather multifarious duties as my excuse for the delay; in truth I was desirous of taking some little pains with my reply, and it has been difficult for me to find the time.

I think with you that the blue frock coat, and felt hat with a feather, with perhaps the Austrian undress cap, will be the most appropriate uniform, the grey coatee is rather behind the age.

If the academy is in the Pine Barrens, it would seem that the period from September 1 to June 20, with the two examinations you speak of, would answer every purpose. It would be almost impossible to have an encampment, I should suppose, yet you might in a very few days teach them how to pitch tents, and the more important parts of camp duty, such as guard duty, construction of field kitchens and ovens, huts for pioneers, etc.

You will find in Captain Marcy’s new book The Prairie Traveller a great deal of invaluable information in reference to camps, taking care of animals, etc., on the prairies. I think you would find it worth while, if not to make it a text book, to require or advise to students to procure copies. It is a book they will read with great interest and profit — it fills a vacuum of no little importance.

I think I have at home the plates belonging to the French “Instruction pour l’enseignement de la Gymnastique.” This will give you all the information you need as to the appliances required for a gymnasium. The title is Instruction pour I’enseignement de la Gymnastique dans les corps de troupes et les etablissements militaire (Paris, I. Dumaine).

If my copy is lost I would advise you to import it. There is also a very good little work published by Dumaine, called Extrait de l’Instruction pour l’enseignement de la Gymnastique, etc., par le Capitaine C. d’Argy.

In addition to the regular instruction in the infantry and artillery manuals, I would by all means have daily practice in the gymnasium, or fencing with the foil and bayonet, and the same exercise at least half an hour a day ought to be devoted to this.

With regard to the course of instruction necessary to lay the foundation for a thorough knowledge of engineering, I do not think that the general course at West Point can be materially improved upon. We have all felt the want of practical instruction on certain points when we left West Point — e.g. in the actual use of instruments, both surveying and astronomical, topography and field sketches, railway engineering, etc. — but it is impossible to do everything in a limited time, and I would suggest that you follow in the main the West Point course, retrenching a little from some of the higher branches and adding a little to the practical instruction.

I know of no complete work on the construction of railways, it is thus far essentially a practical business. Collum and Holley’s work on European Railways contains some valuable information. Lardner on the Steam Engine, Parbour on the Locomotive and Steam Engine, Collum on the Locomotive are all useful. Borden’s Formula for the Location and Construction of Railroads, Haupt on Bridge construction, Moseley’s Mechanical Engineering, Edwin Clarke on the Brittania and Conivay Tubular Bridges, Arolis series of Rudimentary treatise on Engineering, etc., are all of value.

I regret that I am rather pushed for time tonight, as I would have liked to write more fully, but I start for St. Paul in the morning and must do the best I can in a limited time. If I can give you any further information it will afford me great pleasure to do so at any time. With my best wishes for your success in Louisiana, I am very truly yours, GEO. B. McCLELLAN.

In October, 1859, Sherman started for Louisiana but stopped at St. Louis to attend to business affairs and to visit friends. From here he wrote to General Graham and from Cairo and Baton Rouge he wrote to Mrs. Sherman who, it was decided, could not go to Louisiana until the superintendent’s house should be built.

W. T. SHERMAN TO G. MASON GRAHAM

St. Louis, Mo., Sunday, Oct. 23, 1859.

Dear Sir: . . . It is absolutely impossible for me to leave here before Thursday of this week, the 27th, as I have some old matters of business here which I have put oft until now. I was delayed two or three days by the low water of the Missouri. Therefore, however much I would like to be with you on the “Lizzie Simmons,” I must not attempt it.

I will, if there be any faith in steamboats, be at Baton Rouge, Nov. 5 and I suppose I have made a mistake in promising to see the governor at all, instead of the committee of trustees, to whom is left the preparation of things; still, as I have written the governor to that effect, I must do so, but will not delay an unnecessary moment, but hurry on to Alexandria and there meet the committee.

Knowing, as you do, the rates of travel, you can better form a judgment when I can reach your Alexandria; and if your committee will have progressed in their work they may go on, with a certainty that I will zealously enter on any task they may assign me. It seems to me no time is to be lost in preparing regulations and circulars for very wide circulation among the planters whose sons are to be cadets.

But we will soon meet and go to work, and I begin to feel now that we have a noble task and are bound to succeed.

W. T. SHERMAN TO MRS. SHERMAN

Steamer L. M. Kennett [at Cairo], Saturday, Oct. 29, 1859.

. . . Should my health utterly fail me or abolition drive me and all moderate men from the South, then we can retreat down the Hocking and exist until time puts us away under ground. This is not poetically expressed but is the basis of my present plans.

I find southern men, even as well informed as — as big fools as the abolitionists. Though Brown’s whole expedition proves clearly that [while] the northern people oppose slavery in the abstract, yet very few [will] go so far as to act. Yet the extreme southrons pretend to think that the northern people have nothing to do but to steal niggers and to preach sedition.

John’s position and Tom’s may force me at times to appear opposed to extreme southern views, or they may attempt to extract from me promises I will not give, and it may be that this position as the head of a military college, south may be inconsistent with decent independence. I don’t much apprehend such a state of case, still feeling runs so high, where a nigger is concerned, that like religious questions, common sense is disregarded, and knowledge of the character of mankind in such cases leads me to point out a combination of events that may yet operate on our future.

I have heard men of good sense say that the union of the states any longer was impossible, and that the South was preparing for a change. If such a change be contemplated and overt acts be attempted of course I will not go with the South, because with slavery and the whole civilized world opposed to it, they in case of leaving the union will have worse wars and tumults than now distinguish Mexico. If I have to fight here after I prefer an open country and white enemies. I merely allude to these things now because I have heard a good deal lately about such things, and generally that the Southern States by military colleges and organizations were looking to a dissolution of the Union. If they design to protect themselves against negroes and abolitionists I will help; if they propose to leave the Union on account of a supposed fact that the northern people are all abolitionists like Giddings and Brown then I will stand by Ohio and the northwest.

I am on a common kind of boat. River low. Fare eighteen dollars. A hard set aboard; but at Cairo I suppose we take aboard the railroad passengers, a better class. I have all my traps safe aboard, will land my bed and boxes at Red River, will go on to Baton Rouge, and then be governed by circumstances.

The weather is clear and cold and I have a bad cough, asthma of course, but hope to be better tomorrow. I have a stateroom to myself, but at Cairo suppose we will have a crowd; if possible I will keep a room to myself in case I want to burn the paper of which I will have some left, but in case of a second person being put in I can sleep by day and sit up at night, all pretty much the same in the long run. . .

W. T. SHERMAN TO MRS. SHERMAN

Baton Rouge, Sunday, November 6, 1859.

I wrote you from the Kennett at Cairo — but not from Memphis. I got here last night about dark, the very day I had appointed, but so late in the day that when I called at the governor’s residence I found he had gone to a wedding. I have not yet seen him, and as tomorrow is the great election day of this state I hear that he is going down to New Orleans to-day. So I got up early, and as soon as I finish this letter, I will go again.

I have been to the post-office and learn that several letters have come for me, all of which were sent to the governor. Captain Ricketts of the army, commanding officer at the barracks, found me last night, and has told me all the news, says that they were much pleased at my accepting the place, and that all place great reliance on me, that the place at Alexandria selected for the school is famous for salubrity, never has been visited by yellow fever and therefore is better adapted for the purpose than this place. He thinks that I will have one of the best places in the country, and that I will be treated with great consideration by the legislature and authorities of the state. I will have plenty to do be tween this and the time for opening of school. I have yet seen nobody connected with the school and suppose all are waiting for me at Alexandria, where I will go tomorrow.

II. PREPARING FOR THE OPENING OF THE SEMINARY

First impressions of the Red River Valley. General Graham. The Seminary Building. Preparations to be made. Finances of the school Servants and laborers. Welcome from Braxton Bragg. Sherman’s account of his first weeks- in Louisiana. He goes to the Seminary to live. Making rules for the Seminary. The work at the Seminary. The Seminary location. Sherman at work on the regulations. The difficulty of procuring text-books. Governor Moore on educational conditions in Louisiana. Meeting of the supervisors. Opposition to the military system. Professors notified to come to the Seminary. Two factions in the Board of Supervisors. Purchase of supplies in New Orleans. Danger that John Sherman’s political course may embarrass W. T. Sherman in Louisiana. Helper’s Impending Crisis. Sherman’s views on slavery “are good enough for this country.” Appointment of cadets. Braxton Bragg on Seminary affairs. Ready for the opening of the Seminary. Lack of dwelling houses near the Seminary. Slavery and politics. Final preparations for opening. Sherman and the negro servants.

After a short stay in Baton Rouge for the purpose of consulting Governor Wickliffe, Sherman went to Alexandria. The newspapers that mentioned his coming were crowded with news of the John Brown raid and the trial of Brown and his fol lowers. If Sherman had a sense of humor he probably sent copies of the Louisiana Democrat to his brother John. To Mrs. Sherman he wrote on November 12 giving his first impressions of Louisiana.

Alexandria, La., Sunday, Nov. 12 [1859]. I wrote you a hasty letter yesterday whilst the stage was waiting. General Graham and others have been with me every moment so that I was unable to steal a moment’s time to write you. I left the wharf boat at the mouth of Red River, a dirty, poor concern where I laid over one day, the stage only coming up tri-weekly, and at nine o’clock at night started with an overcrowded stage, nine in and two out with driver, four good horses.

Troy coach, road dead level and very dusty, lying along the banks of bayous which cut up the country like a net work. Along these bayous lie the plantations rich in sugar and cotton such as you remember along the Mississippi at Baton Rouge.

We rode all night, a fine moonlight, and before breakfast at a plantation we were hailed by Judge Boyce who rode with us the rest of the journey. His plantation is twenty-five miles further up, but he has lived here since 1826 and knows everybody. He insisted on my stopping with him at the plantation of Mr. Moore, who is just elected governor of Louisiana for the coming four years, and who in that capacity will be President of the Board of Supervisors, who control the Seminary of Learning, and whose friendship and confidence it is important I should secure. He sent us into town in his own carriage. Alexandria isn’t much of a town, and the tavern where I am, Mrs. Fellow’s, a common rate concern, as all southern taverns out of large cities are. Still I have a good room opening into the parlor.

General Graham came in from his plantation nine miles west of this, and has been with me ever since. At this moment he is at church, the Episcopal. He will go out home tonight and to-morrow I go likewise, when we are to have a formal meeting to arrange some rules and regulations, also agree on the system of study. He is the person who has from the start carried on the business. He was at West Point, but did not graduate, but he has an unlimited admiration of the system of discipline and study. He is about fifty-five years, rather small, exceedingly particular and methodical, and altogether different from his brother, the general.

The building is a gorgeous palace, altogether too good for its purpose, stands on a high hill three miles north of this. It has four hundred acres of poor soil, but fine pine and oak trees, a single large building. Like most bodies they have spent all their money on the naked building, trusting to the legislature for further means to provide furniture, etc. All this is to be done, and they agree to put me in charge at once, and enable me to provide before January 1 the tables, desks, chairs, blackboards, etc., the best I can in time for January i, and as this is a mere village I must procure all things from New Orleans, and may have to go down early next month. But for the present I shall go to General Graham’s tomorrow, be there some days, return here and then remove to the college, where I will establish myself and direct in person the construction of such things as may be made there.

There is no family near enough for me to board, so I will get the cook who provides for the carpenters to give me my meals.

It is the design to erect two buildings for the professors, but I doubt whether the legislature will give any more, $135,000 having already been expended. The institution, styled by law the Seminary of Learning, has an annual endowment of $8,100, but it is necessary for the legislature to appropriate this annually, and as they do not meet till the third Monday in January, I don’t see how we can get any money before hand. I think when the appropriation is made, however, my salary will be allowed from November 1.

When I first got here it was hot, but yesterday it changed, and it is now very cold. I have a fire here, but several windows are broken, and the room is as cold as a barn, and the lazy negroes have to be driven to bring in wood.

I expect plenty of trouble from this source, the high wages of servants and the necessity to push them all the time to do anything. I would hire whites, but suppose it would be advisable and good policy to submit to the blacks for the present.

On arrival here I found your and Minnie’s letters, seven days in coming, which is better time than I expected. Mails come here tri-weekly by stage by the route I came. . .

Braxton Bragg, formerly captain of the artillery company in which Sherman was a lieutenant during the forties, wrote from his plantation welcoming his old comrade to Louisiana.

Near Thibodaux, La., November 13, 1859.

My Dear Sherman: It was a great pleasure to receive your note from Baton Rouge, and I sincerely hope that we may soon meet. I should have written to you at once on seeing your election to the important position you are to fill, but did not know where to find you. The announcement gave me very great pleasure, though my influence to some extent was given against you, never dreaming you could be an aspirant. I had united with many gentlemen in New Orleans to recommend Professor Sears, with whom I have no acquaintance, but simply on the ground of his being a graduate of West Point. Indeed, my letter was general, and might have applied to any graduate. Had I known your application I should have attended personally to forward your wishes. But as it is all is well.

Since seeing your appointment I have taken pains to try and advance the institution, and several friends speak of sending their sons. Whatever is in my power will be most cheerfully done for your personal interest, and for the institution generally. We must meet, but it is impossible for me to leave home now. Until nearly Christmas I shall be overrun with business, or rather confined by it. We are in the midst of [sugar] manufacturing, and a cold spell is now on us which inflicts a heavy loss every day lost. I even work on Sunday from this time to the end.

At home I have leisure, and am most happy to see friends. Kilburn, who is stationed in the city, [is] coming tomorrow to spend a few days. Why can’t you do so? You can take dinner with me after breakfast in the city. Kilburn can put you in the way, should you have time to come down. I heard something of your misfortunes and sympathised most deeply with you, but it is not too late for a man of your energy and ability to repair such a disaster.

Your institution I hope will prove a success. It is fairly endowed and has strong and enthusiastic friends. Among them you will find the master spirit my friend, General G. Mason Graham. My acquaintance with him was very short, but very agreeable. Friendships formed under the enemy’s guns ought to last. I knew he liked me, and I admired his gallantry and devotion. Present my regards to him. You may safely trust to his friendship. Our new governor will be your friend, too. He is a plain man, but of excellent character, business habits and very large fortune, placing him above temptation and demagogery. Your professor of mathematics, a foreigner is very highly spoken of; the others I do not know.

Mrs. Sherman and the little ones are not with you I suppose from your not mentioning them. We should be most happy to see them when they come to join you. In the meantime, when you can see enough to form any plan, let me hear from you again, and when and where we may meet. About January 1, I expect to be in Baton Rouge.

Accept my cordial wishes for your success, and happiness.

About the time of the arrival of the new superintendent the Louisiana Democrat [Nov. 10, 1859] had the following editorial notices of the Seminary and its officers.

We would respectfully ask it as a special favor from our contemporaries in other parishes and in the city that they would notice the fact that the Louisiana State Seminary will go into operation on the first day of the incoming new year. The magnificent building, large enough to accommodate a fine company of cadets, is now nearly ready for their reception. One of the professors, Dr. Anthony Vallas, the distinguished author of valuable mathematical works, arrived some days ago. Major Sherman, the superintendent, is on his way hither and all the accomplished corps will be on the ground in ample season to aid in organizing this new institution. . . The institution will in all probability be completely organized before the day fixed for the initiation of its active career of usefulness.

Applications for cadetships or admission as pupils must be addressed to the Board of Supervisors through its president and directed to this place, and not to individual members of the Board. Applicants must be fifteen years of age, and residents of Louisiana. Cadets are to be appointed by the Board in equal numbers from the several senatorial districts. There being thirty-two senatorial districts and the Seminary building being capable of accommodating one hundred and sixty cadets the proportion will be about five appointments from each District. . .

The unrivalled salubrity of its location, the convenience and elegance of its chief building, the munificent donation from the federal government which secures its independent support, and a full corps of teachers of eminent attainments and superior capacity for instruction, will combine to place the Military Seminary of Louisiana among the first seats of learning in the South.

We note with pleasure that a distinguished officer of the U.S. Army, a graduate of West Point and a Creole of Louisiana, Major Beauregard, of New Orleans, has already made application to the Board for the appointment of two sons as cadets. This appreciation of our new state institution on the part of this worthy officer is significant. . .

Sherman in his Memoirs [vol. i, 172] gives a more connected account of the first weeks of his work in Louisiana, from his arrival in Baton Rouge on November 5 to November 18 when he moved to the Seminary building in order to supervise the completion of the carpenter’s work and the equipment of the building.

In the autumn of 1859, having made arrangements for my family to remain in Lancaster, I proceeded, via Columbus, Cincinnati, and Louisville, to Baton Rouge, Louisiana, where I reported for duty to Governor Wickliffe, who, by virtue of his office, was the president of the Board of Supervisors of the institution over which I was called to preside. He explained to me the act of the legislature under which the institution was founded; told me that the building was situated near Alexandria, in the Parish of Rapides, and was substantially finished; that the future management would rest with a Board of Supervisors, mostly citizens of Rapides Parish, where also resided the governor-elect, T. O. Moore, who would soon succeed him in his office as governor and president ex officio; and advised me to go at once to Alexandria, and put myself in communication with Moore and the supervisors.

Accordingly I took a boat at Baton Rouge, for the mouth of Red River. The river being low, and its navigation precarious, I there took the regular mail-coach, as the more certain conveyance, and continued on toward Alexandria. I found, as a fellow-passenger in the coach, Judge Henry Boyce, of the United States District Court, with whom I had made acquaintance years before, at St. Louis, and, as we neared Alexandria, he proposed that we should stop at Governor Moore’s and spend the night. Moore’s house and plantation were on Bayou Robert, about eight miles from Alexandria. We found him at home, with his wife and a married daughter, and spent the night there. He sent us forward to Alexandria the next morning, in his own carriage.

On arriving at Alexandria, I put up at an inn, or boarding-house, and almost immediately thereafter went about ten miles farther up Bayou Rapides, to the plantation and house of General G. Mason Graham, to whom I looked as the principal man with whom I had to deal. He was a high-toned gentleman, and his whole heart was in the enterprise. He at once put me at ease. We acted together most cordially from that time forth, and it was at his house that all the details of the Seminary were arranged.

We first visited the college-building together. It was located on an old country place of four hundred acres of pine-land, with numerous springs, and the building was very large and handsome. A carpenter, named James, resided there, and had the general charge of the property; but, as there was not a table, chair, black-board, or anything on hand, necessary for a beginning, I concluded to quarter myself in one of the rooms of the Seminary, and board with an old black woman who cooked for James, so that I might personally push forward the necessary preparations. There was an old rail-fence about the place, and a large pile of boards in front. I immediately engaged four carpenters, and set them at work to make out of these boards mess-tables, benches, black-boards, etc. I also opened a correspondence with the professors-elect, and with all parties of influence in the state, who were interested in our work.

In November a committee of the Board of Supervisors met with Sherman, Vallas, and St. Ange to make regulations for the government of the school and to arrange a course of study. The name “Louisiana State Seminary of Learning and Military Academy” was adopted. Several expressions in Sherman’s correspondence indicate that he considered the name a monstrosity. A circular dated November 17, prepared by Sherman, was sent out by Governor Wickliffe announcing the approaching opening of the school.

During November Sherman was busied at the Seminary urging the construction work to completion, clearing the building of rubbish and getting it ready for equipment. In his correspondence with Mrs. Sherman and General Graham he describes his daily occupations.

W. T. SHERMAN TO MRS. SHERMAN

Alexandria, Seminary of Learning,

Nov. 19, 1859.

Since my last I have been out to General Graham’s who has a large plantation on Bayou Rapides, nine miles from Alexandria. There met Graham and Whittington, and Sherman, Vallas, and St. Ange, professors, to make rules for the new institution after the model of the Virginia Military Institute. We took their regulations, omitted part, altered other and innovated to suit this case, and as a result I have it all to write over and prepare for the printer.

Yesterday I moved my things out and am now in the college building, have taken two rooms in the southwest tower and shall make the large adjoining room the office, so as to be convenient. There are five carpenters employed here and I take my meals with them.

It is only three miles to Alexandria. I walked out yesterday, and in this morning; but Captain Jarreau, who is appointed steward, lent me a horse for the keeping, so that hereafter I will have a horse to ride about the country; but for some days I will have writing enough to do, and afterwards may have to go down to New Orleans to buy furniture, of which the building is absolutely without, being brand new. The weather has been excessively dry here, but yesterday it rained hard and last night it thundered hard. Today was fine clear and bright like Charleston. . .

W. T. SHERMAN TO G. MASON GRAHAM

Seminary Of Learning, Alexandria, Nov. 21, 1859.

Dear General: . . . The entire article you call Mr. Boyce’s was written by me rather hastily, and has some typographical errors which I will take the liberty to correct, though I wrote it rather to give Mr. B. the substance of an article from himself, but he inserted it without change, making it rather meagre and curt. Still what we need is publicity as soon as possible. I think all the appointments should be made absolutely and finally by say December 10, that we may know the number of books and articles absolutely requisite by that date. By that time we can know exactly what may be procured here and what of necessity must come from New Orleans.

I will keep a note of my ferriages, which I prefer, as it is unsafe to trust the account of the ferryman. If the Board think I am entitled to my salary from November 1 then I would not ask renumeration, but if all salaries are by law, or propriety, fixed for January 1, then I would ask simply reimbursement of actual outlays, to which end I will keep a note of my expenses.

I have been to see Mr. Manning, Dr. Smith, Mr. Ryan, and Henarie several times and will renew my visits and on all proper occasions will touch on the points suggested. If we have, say one hundred at the start it might be well to open with a speech say from Mr. Manning himself, and if Governor Moore could also be present, it would have a good effect and convince these gentlemen that we want the development of as much literary talent as possible.

For my part I am willing that as much time may be given to literary pursuits as the Board of Supervisors may prefer. It will in no wise interfere with the military rule. Only what mathematical studies we do undertake let us make them thorough and not superficial. I have a couple of letters, one from Major Barnard, a very distinguished scholar and major of engineers, written in a very bad hand, which I send with this, for you to decipher if possible. I enclose also for your perusal one from Gilmore and Bragg.

I have had such absolute control of business for some years, that I find myself running off with the bit in my teeth. I ask you as a friend to check me if you see me usurping the province of the directory.

W. T. SHERMAN TO MRS. SHERMAN

Seminary Of Learning, Alexandria, Nov. 25, 1859.

I am still out here at the Seminary, pushing on the work as fast as possible, but people don’t work hard down here. The weather has been warm and spring-like, but tonight the wind is piping and betokens rain. This is Friday. I have been writing all week, the regulations, and have been sending off circulars — indeed everything is backward, and it will keep us moving to be ready for cadets January 1. The Board of Supervisors are to meet on Monday, and I will submit to them the regulations and lists of articles indispensably necessary, and I suppose I will be sent to New Orleans to make the purchases.

The planters about Alexandria are rich but the town is a poor concern. Nothing like furniture can be had. Everybody orders from New Orleans. General Graham is at his plantation nine miles from Alexandria and twelve from here. I get a note from him every day urging me to assume all responsibility as he and all the supervisors are busy at their cotton or sugar.

I believe I have fully described the locality and the fact that although the building for the Seminary is in itself very fine, yet it is solitary and alone in the country and in no wise suited for families. Of course I will permit no family to live in the building. There happens to be one house about one-fourth mile to the rear, belonging to one McCoy in New Orleans, but that is rented by Mr. Vallas, the professor of mathematics, who now occupies it with his family, wife and seven children. They are Hungarians and he is an Episcopal Clergyman, but his religion don’t hurt him much. He seems a pleasant enough man, fifty years old, fat, easy and comfortable. . . They have an Irishman and wife as servants and have plenty of complaints. The house is leaky and full of holes, so that they can hardly keep a candle burning when the wind is boisterous. Indeed the house was built for summer use and calculated to catch as much wind as possible. The design is to ask the legislature to appropriate for two professors’ houses for Vallas and ourselves.

If they appropriate I will have the building and will of course see to their comfort, but I will make no calculations until the amount is settled on. I fear the cost of the building will deter the legislature from appropriating until the institution begins to make friends.

The new governor, Moore, lives near Alexandria and will be highly favorable to liberal appropriation. We have fine springs of pure water all round, and I doubt not the place is very healthy. Indeed there is nothing to make it otherwise unless the long hot summers create disease. I am now comparatively free of my cough and am in about usual condition — have to burn nitre paper occasionally. It is very lonely here indeed. Nobody to talk to but the carpenters and sitting here alone in this great big house away out in the pine wood is not cheerful. . .

W. T. SHERMAN TO G. MASON GRAHAM

Seminary, Nov. 25, 1859.

Dear General: Young Mr. Jarreau is now here and says his wagon is near at hand, with a quarter of mutton for Mr. Vallas and myself. As I am staying with “carpenters’ mess,” I thank you for the favor and will see that Mr. Vallas gets the whole with your compliments. Work progresses slow, but sure. I have the regulations done and several other papers ready for the meeting Monday. As time passes, and Mr. Vallas is not certain that he can get one hundred copies of Algebra at New Orleans I have ordered them of the publisher in New York. . .

Please let Mr. St. Ange give you the title of his text books, grammar and dictionary. All other text books, ought to be approved by the Academic Board, but as that can’t assemble in time, we must take for granted that these preliminary books are absolutely required in advance. I take it for granted the particular grammar and dictionary can be had in New Orleans. . .

To Thomas Ewing, his father-in-law, Sherman wrote on November 27, in regard to the Seminary and about educational conditions in Louisiana.

A minority of the Board of Supervisors was opposed to the military system of government which was championed by General Graham. This opposition which gave trouble to Graham and Sherman is hinted at in the letter from Graham to Governor WicklifTe given below. Public opinion supported Graham’s policy. This is indicated by the two newspaper editorials from the Madison Democrat and the Louisiana Democrat, which are typical press notices.

W. T. SHERMAN TO THOMAS EWING

Seminary Of Learning,

near Alexandria, La.,

Nov. 27, 1859.

Dear Sir: . . . Congress granted to Louisiana long ago, some thirty years, certain lands for a Seminary of Learning. These lands have been from time to time sold and the state now holds the money in trust, giving annually the interest sum $8100.

The accrued interest and more too has been expended in an elegant structure, only too good and costly for its purpose and location. The management has after a series of changes devolved on a Board of Supervisors, composed of fourteen gentlemen of whom the governor is ex-officio president and the superintendent of public education a member. These have selected five professors to whom is entrusted the management of the Seminary. The state has imposed the condition of educating sixteen free of charge for rent, tuition, and board. . .

This building is three miles from Alexandria in a neighborhood not at all settled, as the land here is poor and unfit for cultivation, all the alluvial land being on the south side of the Red River. There are therefore no houses here or near for families, and to remedy this an appropriation will also be asked to build two suitable houses for the married professors, Vallas and myself.

Governor Moore, just elected for four years, says that all educational attempts in Louisiana hitherto failed, mostly because religion has crept in and made the schools and colleges sectarian, which does not suit the promiscuous class who live here. He doubts whether at the start the legislature will feel disposed to depart from recent custom of refusing all such applications, but doubts not if we can for a year or two make good showing, and avoid the breakers that have destroyed hitherto endowed colleges, that this will be fostered and patronized to a high degree.

I shall therefore devote my attention to success, before I give my thoughts to personal advantage; and I find too much reliance is placed on me. I have no doubt I can discipline it and maybe control the system of studies to make it a more practical school than any hereabouts. And as parents are wealthy and willing to pay freely it may be we can get along for a time with little legislative aid further than we can claim as a right.