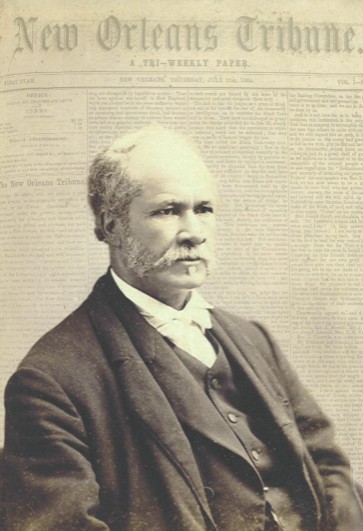

Louis Charles Roudanez.

“Is the Black Code Still in Force?”

© Roudanez: History and Legacy.

Used by permission.

All rights reserved.

Introduction

BY

Mark Charles Roudané

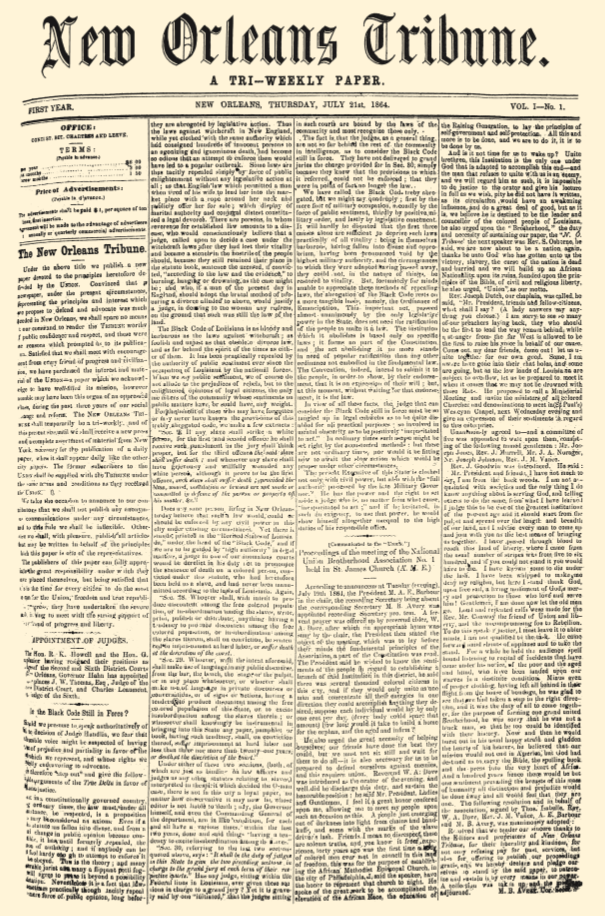

#TDIH. 158 years ago, America’s first Black daily newspaper began publication on July 21, 1864. The New Orleans Tribune was a magnificent expression of Black resistance. The newspaper’s first editorial “Is the Black Code Still in Force?” pointedly thumbed its nose at standing laws that stipulated “Whoever shall, with intent to produce discontent among the free colored population, or insubordination among the slaves, write, print, publish or distribute anything having a tendency to produce discontent among the free colored population, or insubordination among the slaves therein, shall on conviction, be sentenced to imprisonment at hard labor, or suffer death at the discretion of the court.”

Read the full editorial below, republished by Roudanez History & Legacy.

Is the Black Code Still in Force?

The Black Code of Louisiana is as bloody and barbarous as the laws against witchcraft; as foolish and unjust as that obsolete divorce law, and as far behind the spirit of the times as either of them. It has been practically repealed by the authority of public sentiment ever since the occupation of Louisiana by the national forces. When we say public sentiment, we of course do not allude to the prejudices of rebels, but to the enlightened opinions of loyal citizens, the only members of the community whose sentiments on public matters have, or should have, any weight. For the benefit of those who may have forgotten or may never have known the provisions of this trebly abrogated code, we make a few extracts:

“Sec. 9. If any slave shall strike a white person, for the first and second offense he shall receive such punishment as the jury shall think proper, but for the third offence the said slave shall suffer death; and whenever any slave shall have grievously and willfully wounded any white person, although it prove to be the first offense, such slave shall suffer death; provided the blow, wound, mutilation or bruises are not made or committed in defense of the person or property of his master.”

Does any sane person living in New Orleans today believe that such a law would, could or should be enforced by any civil power in this city under existing circumstances? Yet there it stands, printed in the “Revised Statutes of Louisiana,” under the head of the “Black Code,” and if we are to be guided by “high authority” in legal matters, a judge in one of our anomalous courts would be derelict in his duty not to pronounce the sentence of death on a colored person, convicted under this statute, who had heretofore been held as a slave, and had never been manumitted according to the laws of Louisiana.

Again, “Sec. 28. Whoever shall, with intent to produce discontent among the free colored population, or insubordination among the slaves, write, print, publish or distribute anything having a tendency to produce discontent among the free colored population, or insubordination among the slaves therein, shall on conviction, be sentenced to imprisonment at hard labor, or suffer death at the discretion of the court.”

“Sec. 29. Whoever, with the intent aforesaid, shall make use of language in any public discourse, from the bar, the bench, the state or the pulpit, or in any place whatsoever, or whoever shall make use of language in private discourse or conversations, or of signs or actions, having a tendency to produce discontent among the free colored population of this State, or to excite insubordination among the slaves therein; or whosoever shall knowingly be instrumental in bringing into this State any paper, pamphlet or book, having such tendency, shall on conviction thereof, sffer imprisonment at hard labor not less than three nore more than twenty-one years, or death, at the discretion of the court.”

Under either of these two sections…there is not in this city a loyal paper, no matter how conservative it may now be, whose editor is not liable to death; nay, The Governor himself, and even the Commanding General of the department, are in like condition, for each and all have at various times, within the last two years alone, done and said things “having a tendency to excite insubordination among the slaves.”

Sec. 30, referring to the last two sections quoted above, says: “It shall be the duty of judges in this State to give the two preceding sections in charge to the grand jury at each term of their respective courts.” Has any judge, sitting within the Federal lines in Louisiana, ever given these sections in charge to a grand jury? Yet it is gravely said by one of the “initiated,” that the judges sitting in such courts are bound by the laws of the community and must recognize those only. The fact is that the judges, as a general thing, are not so far behind the rest of the community in intelligence, as to consider the Black Code still in force. They have not delivered to grand juries the charge provided for in Sec. 30, simply because they know that the provisions to which it referred could not be enforced; that they were in point of fact no longer the law.

We have called the Black Code trebly abrogated, but we might say quadruply; first by the mere fact of military occupation, secondly by the force of public sentiment, thirdly by positive military order, and lastly by legislative enactment. It will hardly be disputed that the first three causes alone are sufficient to deprive such laws practically of all vitality; being in themselves barbarous, having fallen into disuse and opprobrium, having been pronounced void by the highest military authority, and the circumstances to which they were adapted having passed away, they could not, in the nature of things, be restored to vitality.

But, fortunately for minds unable to appreciate these methods of repealing laws, the abrogation of the Black Code rests on a more tangible basis, namely, the Ordinance of Emancipation. This important act, passed almost unanimously by the only legislative power in the State, does not need the ratification of the people to make it a law. The institution which it abolishes is based only on specific laws; it forms no part of the Constitution, and the act abolishing it no more stands in need of popular ratification than any other ordinance not embodied in the fundamental law. The Convention, indeed, intends to submit it to the people, in order to show, by their endorsement, that it is an expression of their will; but, at this moment, without waiting for that endorsement, it is the law.

In view of all these facts, the judge that can consider the Black Code still in force must be so tangled up in legal cobwebs as to be quite disabled for all practical purposes; so involved in mental obscurity as to be positively “incapacitated to act.” In ordinary times such a case might be set right by the accustomed methods; but these are not ordinary times, nor would it be fitting now to await the slow action which would be proper under other circumstances.

The present Executive of this State is clothed not only with civil power, but also with the “full authority possessed by the late Military Governor.” He has the power and the right to set aside a judge who is, no matter from what cause, “incapacitated to act:” and if he hesitated, in such an exigency, to use that power, he would show himself altogether unequal to the high duties of his responsible office.”

Notes

- Black Code. A system of laws governing the treatment of enslaved people and people of color in Louisiana. They were also called the “Code Noir” in the French period and “El Código Negro” in the Spanish period.

Text prepared by:

- Bruce R. Magee

Source

Roudanez, Louis Charles. “Is the Black Code Still in Force?” New Orleans Tribune, 21 July 1864, p. 1. Roudanez: History and Legacy. “Is the Black Code Still in Force?” Facebook, 21 July 2022, 9:51 p.m., https:// www. facebook. com/ 84268593 5851803/ posts/ pfbid02kA jYHqMzS6b wCqu6kA7rV9mc Yvhark1Jnem2h2 so4kqqVNtNZQe JyASUMZF 5tJ78l/ ?d=n. Accessed 25 July 2022. © Roudanez: History and Legacy. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Roudané, Mark Charles. #TDIH. Facebook, 21 July 2022, 9:51 p.m., www. facebook. com/ 84268593 5851803/ posts/ pfbid02kA jYHqMzS6b wCqu6kA7rV9mc Yvhark1Jnem2h2 so4kqqVNtNZQe JyASUMZF 5tJ78l/ ?d=n. Accessed 25 July 2022. © Roudanez: History and Legacy. Used by permission. All rights reserved.