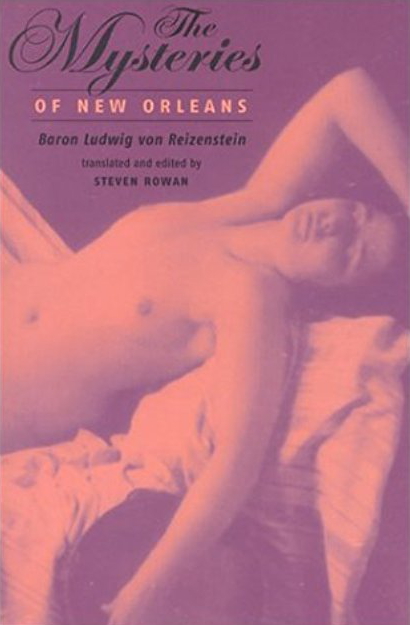

Baron Ludwig von Reizenstein.

Steven Rowan, translator and editor.

“Lesbian Love.”

© Steven Rowan.

Used by permission.

All rights reserved.

Introduction

Reizenstein’s writings document the existence of specifically southern regional literature in the German language. His sensualist and comic sensibility combined with a pervasive sense of doom, and his fictional writings all draw on the German horror and Gothic tradition of E. T. A. Hoffmann and his followers. More a remittance man than a Forty-eighter, Reizenstein did not exploit contemporary political themes, nor was he specifically anticlerical as were most other German novelists then resident in the United States and writing for a German-speaking American audience.

What follows is a chapter from the second book of the novel, which follows characters already sketched in earlier chapters. A German Creole, Orleana, a wealthy and cultivated young woman living on Toulouse Street in New Orleans, has been harassed by a drunken, over-educated German immigrant who is called “The Cocker.” “The Cocker” assumes that Orleana will love him once she gets to know him. Wrong. He invites himself to dinner, and his stupidity and drunkenness culminate in an episode in which he dumps a plate of sweet potatoes into Orleana’s lap and dives in after them, going where no man had ever gone before. “The Cocker” is expelled with extreme prejudice by Orleana when Claudine de Lessure is announced. Claudine has just walked out on her crude husband, who has coolly informed her, “Marriage is the grave of love.”

It is typical of Reizenstein that he challenged the platitudinous moralism of his freethinker colleagues by gratuitously stressing the peculiar sexuality of most of his characters. It is easy to say that Claudine and Orleana are the only sympathetic lovers — really the only “straight” people — in his entire story. They represent an alternative lesbian society flourishing in New Orleans as nowhere else in America. This particular vision of lesbian communal utopias derives from a tradition that ritualizes the sexuality of “others” in society, whether they are repressed monks or women ensconced in harems. When projected specifically on women, such ideal communes recur throughout the history of American popular culture, notably as the Amazon community that is home to Wonder Woman. Despite its dubious parentage and progeny, Reizenstein’s celebration of same-sex love is a landmark in the portrayal of homosexuality in American fiction. The revolutionary nature of Reizenstein’s treatment is underscored by the fact that Jeannette H. Foster, in Sex Variant Women in Literature (1956), was unable to turn up anything as forthright as Reizenstein in the French literature known to her, let alone in English-language literature. The lesbian was usually treated as a lonely aberration. Reizenstein did not hesitate to see the love of Orleana and Claudine as a revolutionary act, a gentle revolt against the domination of males over females, of property over want, of oligarchy over virtue, and of humans over other animal species. The lesbian episode appears to have had some deep personal importance to Reizenstein, since it serves no purpose in moving the plot forward. Needless to say, Reizenstein would have had to wait a long time to find the audience for such a message.

Virtually everyone else in his book suffers from perverted sexuality: the effeminate cross-dressing dandy Emil, his amoral hooker-lover Lucy, the drunken sexist “Cocker” Hahn, the murderous sadistic priest Dubreuil, the necrophiliac rapist Lajos, the timorously incestuous repressed lesbians Frida and Jenny, even the naive North-German cook Urschl (in all likelihood the only white female in nineteenth-century American fiction whose sexual encounter with a black male is portrayed as a comic episode).

Reizenstein’s peculiar vision of New Orleans is worth resurrecting precisely because it crossed the boundaries of acceptable taste in nineteenth-century German America and squatted firmly on the other side. By writing a dark comedy about the fell fate of America, he cut through confused sentimentality to reveal the roots of a clear and present danger. By challenging the platitudes under which freethinkers sought to give lip-service to Christian values while challenging clerical authority, Reizenstein revealed the hypocrisy of a lukewarm semi-humanism. By neglecting to reward the virtue of individuals in order to lambaste the criminality of an entire social order, Reizenstein highlighted the shallow compromises made in the other exemplars of the urban mysteries genre. By articulating his dreadful fantasy of a coming cataclysm, Reizenstein documented beyond a shadow of a doubt the historical existence of a very real southern nightmare. Above all else, the discovery of this work makes us realize how limited our notions were of what could be conceived by a fertile American imagination in the middle of the nineteenth century.

Speak, woman, what am I to give you?

You smile? Aha! Servants! Runners!

Strike off the Baptist’s head!”

2. “She sees on your shoulder too —

As she covers them with kisses —

Three little scars, monuments of desire,

Which he once bit into you.”

“IT is a real shame, my dear Claudine, that it did not occur to you to visit me an hour earlier. My God, what a scene! What a cascade of offences to the spirit, one after another! Don Juan with all his amiability, all his play of the eye which could win the heart of any woman in an instant, the slim, blond Don Juan who rules in Madrid and Zaragossa, Seville and Santillana, on the Guadalquivir and Ebro as utterly as a god on the Ganges, stealing all of Amor’s arrows from his quiver, this Don Juan, this seducer of maidens, terror of husbands — he stood before me, fell to his knees and saw his power and connections go to naught on account of a chair-leg, and all the laurels female adulation and love had wrapped about his brow were torn from his head in an instant. Don Juan has at last found his female conqueror. He will curse the hour, the minute, the second, in which he dared to try for the heart of a German Creole maiden! Don Juan has become a greenhorn in New Orleans.”

Claudine stared at her friend with great eyes. She was all the more amazed by the peculiar manner in which Orleana expressed herself, since she had never noticed any inclination on her behalf for Don Juans. On the contrary, she had always been determined to debunk them without mercy and only give them attention when she wished to show the failings and errors of men. Orleana had always found an energetic opponent in Claudine, who always wished to soften her prejudice against men with time. She had never heard Orleana speak that way before. To speak of men in such a tone! To speak so lightly of Amor, quivers, arrows, hearts, pratfalls, without restraint — oh, oh — what had happened to Orleana?

“I don’t understand you, my dear Orleana — ” That was all Claudine had been able to respond to her dithyrambs. Orleana took a folded note out of a tiny drawer in her desk, whose address was written, or rather smeared, with large Gothic letters, and she handed it to Claudine with a smile, who stopped after reading a single line and stared in her friend’s face with astonishment.

“What does this mean, Orleana, your statements and then this letter — I do not understand you — please, what happened? How did you get this shameful letter — who could have dared to write something like this — Orleana, please explain it to me — I cannot understand it.”

Orleana, who did not want to test her friend’s patience any further, now explained the entire business of the Cocker in detail. His rude conduct at the threshold of the receiving room, his clumsiness at table, the offense he committed when he fell to his knees — in short everything that took place during the encounter, to the very end, all was told to the astonished Claudine.

Orleana, who thought that this droll love affair had provided the right atmosphere for the evening, was no little touched when Claudine declared in a mournful tone suited to touch the heart, “My dear Orleana, I believe you were right; men are incapable of valuing a woman’s love — men are all raw in matters of love.”

“How am I to take that? What made you so reflective all of a sudden?”

When Claudine fell silent, a tear in her eye, Orleana continued: “Your silence disturbs me, my dear friend. How does it happen that you, who were so happy only a short time ago, have suddenly abandoned marveling at and beseeching men to level such a condemnation against them? But I will no longer press you or storm your soul with troublesome questions, my dear Claudine — for your silence and the tears in your eyes tell me that I must be silent where my friend has decided to harbor care in her heart and not reveal it even to her Orleana.”

“Am I that to you!” Claudine interjected vigorously. “And this even at a moment when my heart tells me that I must cut myself off from the entire world and live only for my Orleana — Orleana, Orleana, if you only knew what I still felt for you when I stood at the altar with Albert and you handed me the bridal crown? — Orleana, perhaps it is heaven’s revenge for a crime which I took then only as an innocent child’s game, and only now that I have separated from my husband do I think of this cri…… oh no, no — Orleana, it could not have been a crime that I love you — no, no, no, Orleana…”

“Claudine, Claudine!” Orleana interrupted with a blush, “do you really love me? Oh, so I did not err after all — how often I trembled when I was near to you — and when once you draped your arm around my neck — oh Claudine — if it had been a man, I would have remained as cold as marble — Orleana has never trembled in the presence of a man — and she will tremble in the presence of none in the future. Orleana loves her femininity too much to give it to any the future. Orleana loves her femininity too much to give it to any other than a female friend — to her Claudine — wait a moment,” other than a female friend — to her Claudine — wait a moment,” Orleana interrupted herself with a thought — “didn’t you say you have separated from your husband — or did I hear incorrectly?”

Claudine blushed and paled by turns as she placed her hands in Orleana’s and described the events of that evening when Albert damaged her dignity as spouse so thoroughly through a flippant phrase that he caused a breech that no man on earth could heal.

As we already know, Claudine did not appear at breakfast on the morning after that fateful night, so that Albert had to eat alone. On the same morning, as Albert was rushing to Algiers to visit the two sisters, Claudine’s maid took her note with her on the way to the market and delivered it punctually to her aunt’s in Bourbon Street. The elderly Baroness Alma de St. Marie-Eglise rushed at once to her niece, finding her still in bed.

Claudine’s lines so astounded the old lady and so piqued her curiosity that she could not wait until Claudine came by at the appointed hour. She had to come and see her herself. She could not even wait until the horses had been harnessed. She, who had not set foot on the street in several years without mounting a carriage, rushed like a young girl to the street where her niece lived. She found her still in bed, as mentioned, half awake, in the deepest negligee, her hair loose, tangled and tossed across her naked upper body.

The maid, who had eagerly been following the development of this drama, was sent out by Claudine, who did not want an observer who might not be trustworthy.

One can well imagine the distress the elderly lady felt when Claudine told her in short, decisive words the cause for her note. The old baroness applied all her arts of persuasion to convince her niece to forgive her loveless husband and take him in her arms again.

“‘Marriage is the grave of love!’ — What was he trying to say with that? Nothing at all, my dear child — your Albert loves you as much now as he ever did, and he had no purpose at all when he pronounced this fatuity to you. Albert is one of those young, thoughtless fools — there are thousands of them. They want to know everything, perceive everything, try everything, and in the end they know nothing at all. He got this silly saying from some writer or other, or perhaps he heard it from some over-smart yellow-beak, and he thought to impress you the other night. Albert? What does your Albert know about marriage? The two of you know nothing of the troubles and stresses that come in married life. What does Albert, what do you yourself know about marriage? You have only been married a few months! I lived thirty-five years with Monsieur de Saint-Marie — I can assure you, my dear, unsophisticated child, that it is not all that fatal for a husband not to love you as much as a girl would like. And Monsieur de Saint-Marie was not a man to neglect his wife. Live with one another five or ten years and you will not become upset over some thoughtless, frivolous saying. You do not yet know men, my unsophisticated little Claudine — the more they complain, the more they love. A man who is always carrying you around on his arm, praying to you like a god, speaking courteously to you night and day, constantly seeking to pander to your heart, is not worth much in marriage. Such a man should never be trusted. He would only be doing it to mislead you for some purpose or to do things behind your back, so that when you find it out, your lot would be anything but enviable.

“Look, dumb, silly little Claudine, see how pointlessly you martyr yourself. If Albert didn’t love you, he would never have said what he did; he certainly wanted to put your love to the test. Oh, I could give you many other examples of this! How dreadfully Monsieur de Saint-Marie, my late husband, treated me oftentimes! And did he love me any less? No, my child, to the last moment he bore his Alma in his heart. So calm down and let me hear no more of your unhappy decision. You would certainly deeply regret it in the future if you sacrificed your heart’s peace due to a mere whim or rudeness on the part of your husband. Make up and love one another as emphatically as before, and don’t bother me over such a silly matter — will you promise me that, little Claudine?”

These and other efforts by her aunt could not shake Claudine’s decision. In the end the half-disgusted Baroness gave her consent to a separation of the two spouses, but with the condition that she be able to speak with Albert about it.

Several days later Albert paid the old lady a visit, which ended just as badly. She poured out all her wrath on Albert, and she ended up supporting a divorce as soon as possible.

Once the necessary preparations for this had been made and the legal act of divorce obtained, Claudine moved in with her aunt and Albert lived alone in the same home where he had once passed such fine and sweet hours in the arms of his spouse.

Orleana, who was living in Ocean Springs, on the high bluffs of the Gulf of Mexico, at the time, had not received any news at all from her friend on this matter. It would have been difficult to discover the motive for Claudine’s neglect to do this. Perhaps she thought it more proper to tell her of her troubles on her return.

And so we find the poor sufferer today with her Orleana. And so we find the poor sufferer today with her Orleana.

Softly, softly! Quiet, quiet now! Trust not the night — close the curtains as tightly as possible; don’t talk so openly, for the walls have ears.

Softly, softly! Quietly, quietly, so the evil world cannot hear!

Rubens, Rembrandt, Raphael Santio of Urbino, lend me your brushes; Beethoven, let a fugue vibrate through my arteries and seethe my blood; you, land of the Nibelungs, send me your fiery wines; Canova, give me the mallet you used to make your Paris — or better — Paris, give me your apple, that I may lay it between Orleana and Claudine.

You, Pallas Athena, step aside for a moment, for your armor weighs down your bosom too much — Priapus may leave, too, for here you will find no man at all!

Yet, if it pleases you, my hermaphrodite Ganymede, come and pour your ambrosia for Orleana and Claudine!

“Do you really love me, Claudine?”

“How beautiful you are, Orleana!”

“How beautiful is your dark blond hair, your blue eyes!”

“How splendid your raven-black hair and the midnight of your eyes!”

“How sweet and supple your waist is!”

“How proud and majestic your breasts!”

“How small your white hands are!”

“How pure your arm is, which no man has ever touched!”

“Claudine, this delicate paleness of your face!”

“Orleana, the beautiful blush on your fresh cheeks!”

“Claudine, how harmonious, how moving your voice is!”

“Orleana, how inspiring your words are!”

“Do you really love me, Claudine?”

An authority from ancient Greece tells us that women once lived on the isle of Lesbos who did not allow themselves to be touched by any man, since a whim of nature had given them the gift of being happy among themselves.

If any maid in Greece was blessed with this gift, she rushed to this island to seek a companion for life. When the Romans became lords of Hellas, they transported these women to the City of the Seven Hills and exploited them as slaves, compelling them to assist in the baths.

They lived free in a few places in Magna Grecia, enjoying there the same rights they once had been conceded on their island.

Later, when the Romans were subjected by the Germans, many Later, when the Romans were subjected by the Germans, many went to Lombardy, Switzerland, and southern Germany.

In Switzerland it was most of all Meran where they gathered and found a place for their secretive activities.

Both the Cabots brought along many of them to America, and Sir Walter Raleigh transplanted them to Virginia, where Queen Elizabeth extended them her full favor, protecting them to a surprising degree.

There are many fables about Elizabeth and Raleigh, and the Chronique Scandaleuse has sought in vain to plumb the motives that led the Virgin Queen to withdraw her grace from Raleigh.

Until now no one has discovered — or no one has dared to confess — that the cause was her jealousy of Raleigh due to his relationship with a lesbian lady.

In the art gallery of the new royal palace in Munich is a portrait of this competitor, and her surprising resemblance to Orleana can only be the result of an elective affinity, for Lesbos “produces no children.”

So much for the closer understanding of the mysterious stirrings of feeling on the part of our beautiful Orleana.

Bedchambers where a man seldom or only briefly appears — bedchambers, on whose white carpet only a woman’s foot ever steps — bedchambers on whose beds, sofas, and hangings only the atlas of a woman’s robe whispers by; such bedchambers are a hell of torments and pains for a man, when Amor breaks his arrow and throws it at his feet in disgust as he departs. Whoever enters whole departs sick of heart and soul. Drunk in his senses, he thinks of the atlas robe that rustles at his knee; he presses his hand on his hot brow, and his senses collapse as his fantasy contemplates what the atlas rustles against. It is the veiled image of Saïs, the Cathedral of Love, Sensuality itself which expresses the whole of nature.

It is certainly no crime to lift the veil from this image; certainly it is no sin against the holy of holies of femininity to contemplate it, it is certainly no sin against the Holy Spirit to enter this Cathedral of Love with covered head — but Nature herself is responsible for having wandered from the path — when she creates flowers whose pistils will not accept masculine pollen, whose pistils in fact leave their flower-cup in order to join one with another.

Quietly, quietly; softly, softly now; close the curtains as tightly Quietly, quietly; softly, softly now; close the curtains as tightly as you can; do not speak so loudly, for the walls have ears, too.

“Do you really love me, Claudine?”

“Oh, how the fresh warmth of your proud shoulders drives me wild!”

“How your breasts make my blood boil!”

“Orleana, Orleana, how excitingly loose your clothes are!”

“Claudine, Claudine, how tightly you are corseted!”

“Orleana, Orleana, how easily your clothes fall away!”

“Claudine, Claudine, how difficult it is for me to get these things off you !”

“Orleana, how pure and white your shoulders are!”

“Claudine, where did you get the scars on yours?”

“Orleana, Orleana — Albert did that.”

“And you really love me, Claudine?”

In my garden,

A whole bed full.

I could hardly wait

Until they came, until they bloomed,

So I could pluck them

For my love.

And when they came

Sprouting up

I generously

Sprinkled them with water.

“Buds hung

In fullness, half ready

Your watering

Did them much good.”

But when I came

Out one morning

What did I see — good heavens!

Oh terror, oh horror!

The buds lay broken

Bent on the ground.

I mourned mightily

For the dear departed.

“Now to your beloved

You cannot give Measured Love.

I mourn much for that

For her young life.”

As I said, the hermaphrodite Ganymede may enter without As I said, the hermaphrodite Ganymede may enter without hesitation, his presence does not disturb, and it is high time his divine drink moistened their burning lips.

Come closer, my Ganymede, don’t turn your little nose so high! Almighty Jupiter is long since dead — Olympus is abandoned and empty — the whole race of the gods died out — you must reconcile yourself to serving mortals.

Come in — you’ll find an old friend; see how confused Cupid flits from one lap to another and cannot figure out quite where to begin. You can tell that such visits are a rarity for him!

Quietly, quietly, softly, softly now, so the evil world doesn’t hear.

Close the curtains as tight as you can!

Don’t speak so loudly, for the walls have ears.

“Do you really love me, Claudine?”

“Orleana, Orleana, how embarrassed I am!”

“Claudine, Claudine, how happy I am!”

“Orleana, my angel, where are you taking me?”

“Claudine, my little woman, I want to kiss you!”

“Orleana, Orleana, I’m really embarrassed.”

“No, no, my dear little woman, I am only kissing you!”

“Orleana, oh let me, I want you so much!”

“My little Claudine, my little woman, tremble no more!”

Wherever the law claps love in permanent manacles, where the church proclaims sensual denial, where false modesty and inherited morality keep us from giving nature its rights, then we lie down at the warm breasts of Mother Nature, listening to her secrets and surveying with burning eyes the great mechanism in which every gear bears the word love.

There is rejoicing in all the spheres, the fanfares of the universe resound, wherever love celebrates its triumph. But lightning bolts flash from dark clouds whenever tyrannical law and usurped morality seek to compel the children of earth to smother their vitality and entomb their feelings.

How small and pitiful appears the nattering of parties, how petty the drama even of our own revolution against the titanic struggle of sensuality against law and morality.

“Revolution!” the nun cries out in her sleep, throwing her rosary in the face of the Madonna.

“Revolution!” the priest of the soul-redeeming church mutters as he rips his scapular in shreds.

“Revolution!” thunders the proletariat when it sees the fair

“Revolution!” thunders the proletariat when it sees the fair daughter of Pharaoh. daughter of Pharaoh.

“Revolution!” the slave rattles, when he sees the white child of the planter walking through the dark passageway of cypresses.

“Revolution!” the horse whinnies, mutilated by greed.

“Revolution!” the steer roars, cursing its tormentors with a yoke on its shoulders.

“Revolution!” the women of Lesbos would storm, if we were to rebuke their love.

New Orleans is the Meran of the United States for lesbian ladies, where they hold their mysterious gatherings unhindered and unseen by the argus-eyes of morality. Strangely enough, as everywhere else, they reside only alongside bodies of water, since their norms hold that they cannot do without the nearness of water. So we find them in clubs of twelve to fifteen on the Hercules Quay, along the Pensacola Landing, and all along the entire eastern side of the New Basin.

They have lost their earlier location on Lake Pontchartrain.

They were driven out, in part by the efforts of F——, in part through the efforts of old McDonogh.

My esteemed lady readers will visit one of these settlements in the third volume and be convinced that lesbian ladies are not as bad as they think, and that they are as decent and well mannered as the rest of the world of women, after their fashion.

It was three o’clock when Amor fluttered through the shutters, through which a cooling west wind blew over the slumbering women-friends.

The moon smiled knavishly and the stars glittered with delight as they sighted Cupid flying down Toulouse Street, blushing red from head to foot, with flaccid bow and empty quiver.

Text prepared by:

- Bruce R. Magee

Source

von Reizenstein, Baron Ludwig. “‘Lesbian Love’ from The Mysteries of New Orleans.” Ed. Steven Rowan. The Antioch Review 53.3 (1995): 284-296. JSTOR. Web. 21 Sept. 2017. <http:// www.jstor. org/ stable/ 4613166>. © Steven Rowan. Used by permission. All rights reserved.