Angela Allen Bell.

Kate Dillingham.

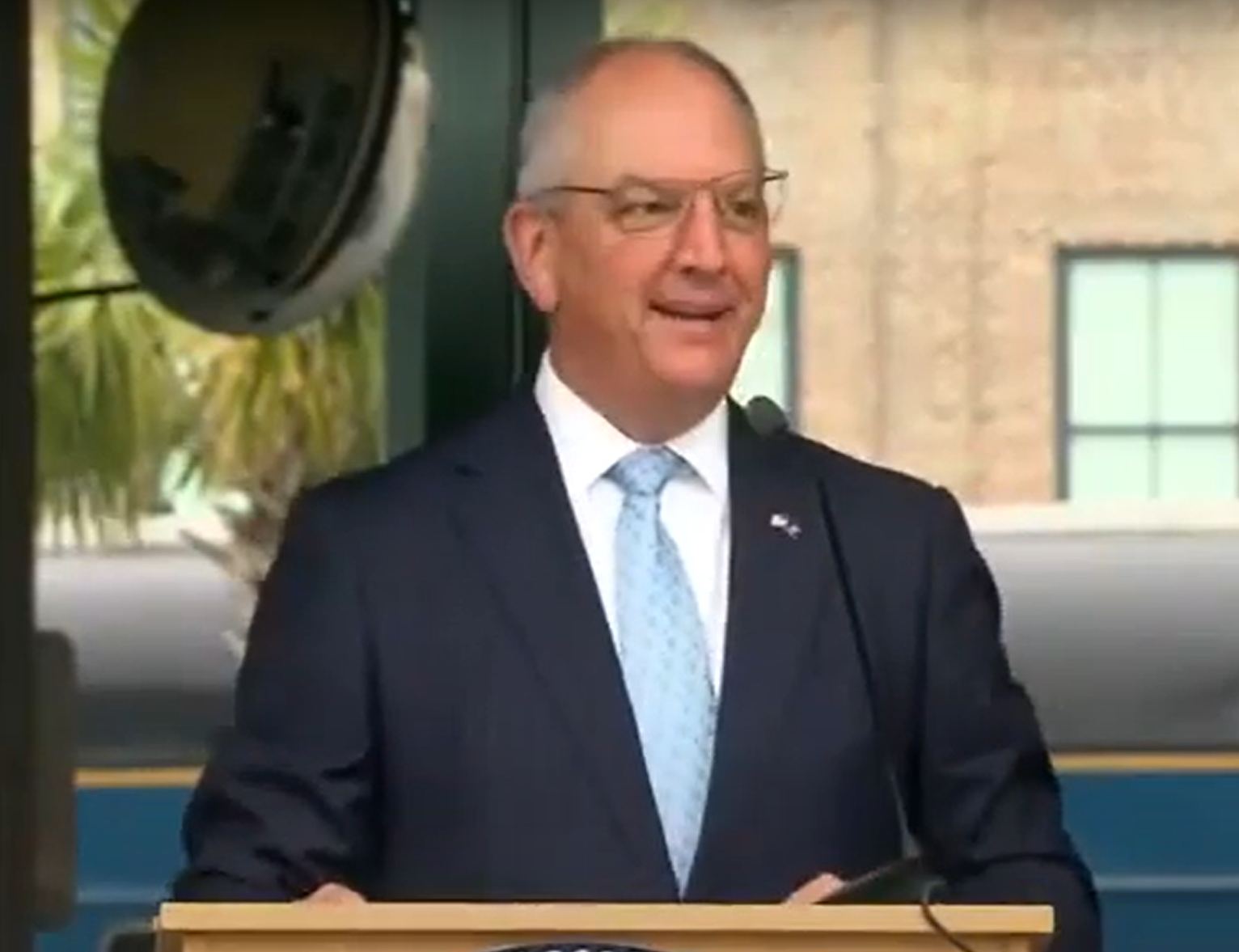

Gov. John Bel Edwards.

Phoebe Ferguson.

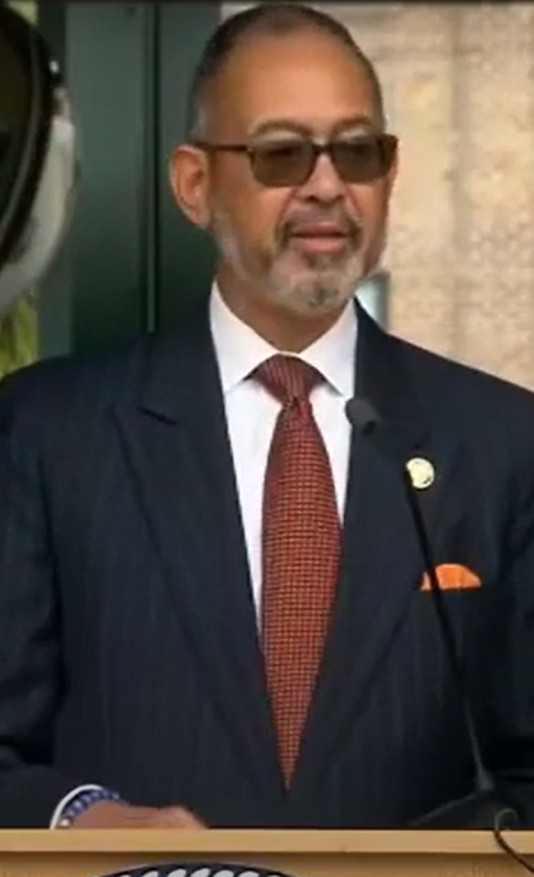

Senator Edwin R. Murray.

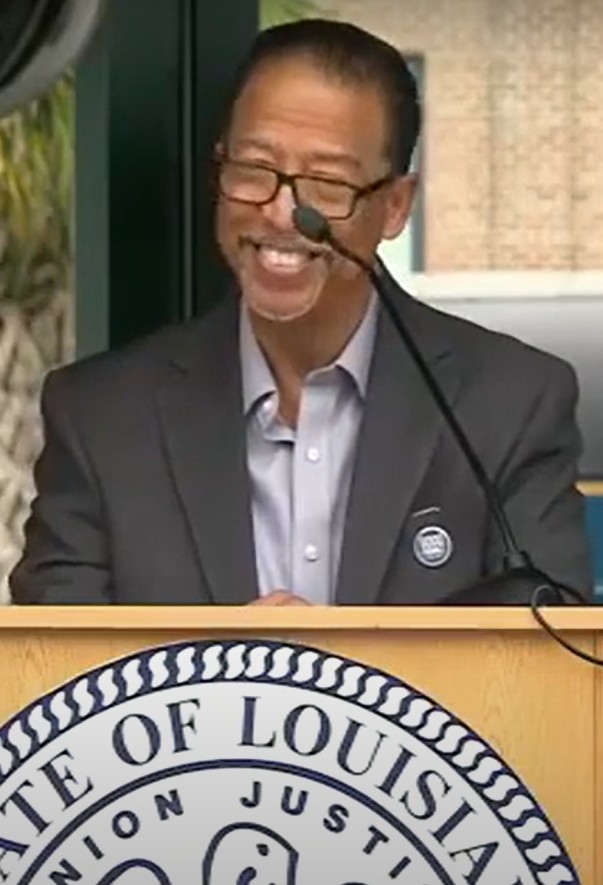

Keith Plessy.

Kyle Wedberg.

District Attorney Jason Rogers Williams.

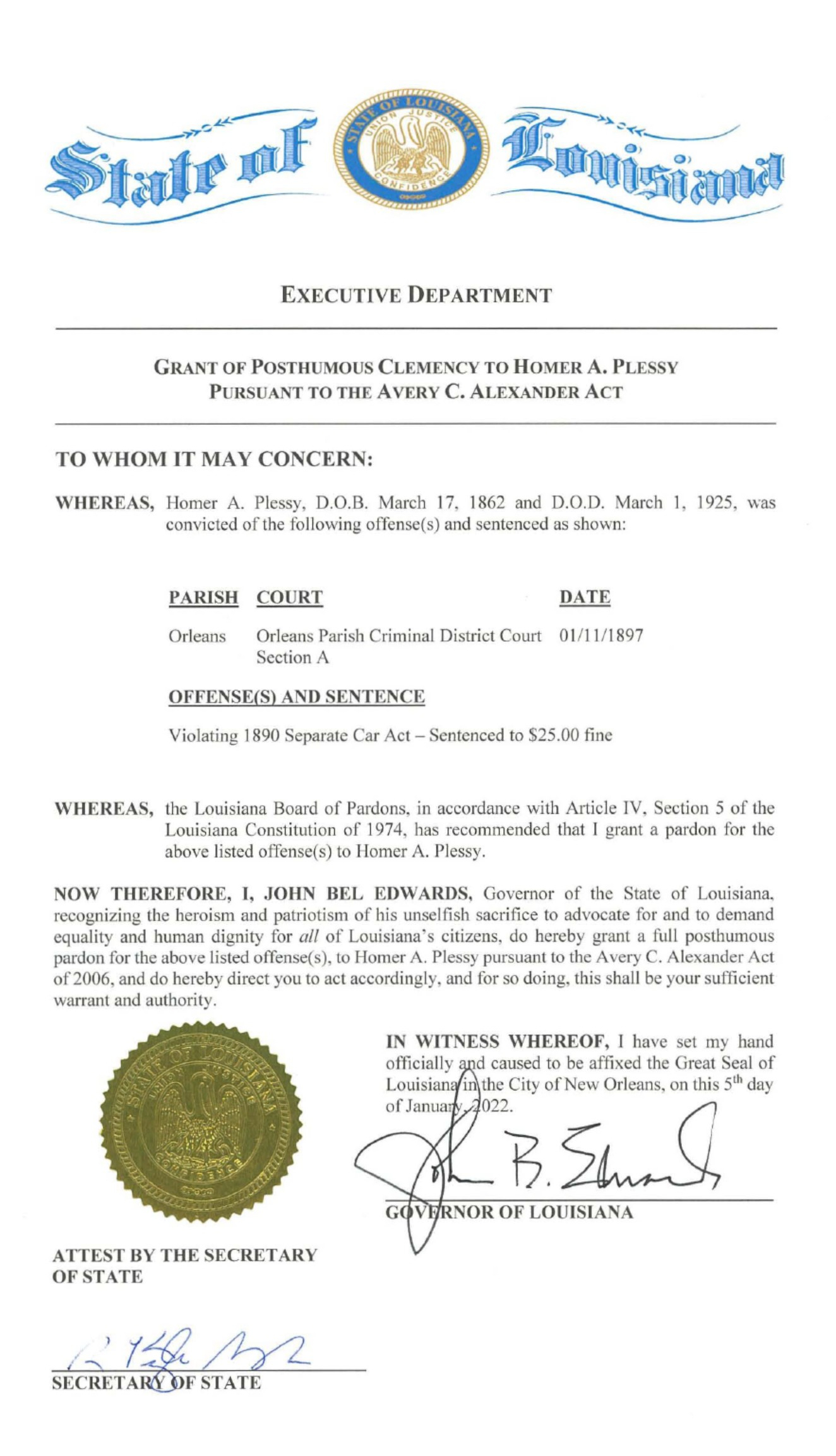

“Grant of Posthumous Clemency to Homer Plessy.”

Signing the Pardon of Homer Plessy.

All of you are here. So, as we prepare to begin today’s program in just a couple of moments, we are going to hear a very special musical performance of “Lift Every Voice and Sing” by Miss Kate Dillingham. She is a professional cellist based in New York City and she is the great great granddaughter of Supreme Court Justice John Marshall Harlan, the lone dissenter in Plessy versus Ferguson. Yes, you may applaud. She will play the very first verse and refrain of lift every voice and sing. Please feel free to stand. The words are in the very back of your program. Enjoy and thank you.

Music: J. Rosamond Johnson

Kyle Wedberg

Thank you for being here today. My name is Kyle Wedberg and welcome to NOCCA. NOCCA is a world-class public arts high school and a proud agency of the state of Louisiana.

We are gathered in this place specifically in this place because place matters. The buildings we are surrounded by were originally built to press and store cotton, the symbolic fruit of America’s original sin. The building I am framed by was later converted into a train station where the citizens’ committee came in 1892 to buy a ticket for Homer Plessy. A few blocks up is where the train stopped and Mister Plessy was asked to change cars. And a hundred thirty years later, we gather in this space, in this specific space. A space where today, hundreds of students walk in every day from every walk of life into this beautiful and challenging act of growing as artists with something to say.

In South African culture, there is a word Muntu. Muntu is the idea that I am because you are, that my humanity is connected to your humanity. It is the idea that separate but equal is not possible and not because of the word ‘equal’ in that equation, but rather because of the word ‘separate’. It’s impossible to separate our humanity. We are because of each other. Our humanity is connected.

I speak of South Africa as we just lost Archbishop Desmond Tutu. In one of his final interviews, Archbishop Tutu was asked how he wished to be remembered in his obituary. His words were, “He loved, he laughed, he cried, he was forgiven, and he forgave.” I offer that this is why we are here in this specific place at this specific time. It is a final lesson from one of our all-time elders. Archbishop Tutu reminds us that sometimes, we must forgive to find forgiveness ourselves.

Thank you for being here today, as we are with and among friends and leaders who recognize this work and will continue to do this work going forward, as civic stewards and stalwarts of this community, of this state, and of this country.

I am honored and to invite to the podium, professor of law, and my future alma mater Southern University, Miss Angela Allen Bell.

Angela Allen Bell

Good morning. I am honored to provide the historical context and the implications of the Plessy versus Ferguson decision. On March the 17th, 1863, Homer Plessy was born in New Orleans to French-speaking people of color. Plessy would earn a living in unremarkable ways. He was first a shoemaker and then later an insurance salesman. But this should not be accepted as evidence that Homer Plessy was an ordinary man. His genes would predestine him to do the extraordinary.

In 1790, Homer Plessy’s white paternal grandfather would begin an interracial relationship here in Louisiana with a free woman of color. In 1860, Homer Plessy’s maternal grandfather would be found advocating for voting rights for blacks. In the 1870s, his stepfather would be found advocating for racial equality. The yearning for dignity and equality was a part of Homer Plessy’s DNA. This led to quite an ambitious agenda outside of work.

Homer Plessy divided his time between an organization that fought for education reform and the citizens committee which existed solely to challenge segregation. In his day, we had the 13th amendment, which abolished chattel slavery. We had a 14th amendment, which established citizenship for the newly emancipated people and equal protection. We even had a 15th amendment, which prevented the deprivation of the vote, as well as multiple civil rights acts.

Plessy struggled to reconcile the indignation of segregation with all of these legal protections. June 7th, 1892, would be the day that Homer Plessy would make law honest. Homer Plessy from this very location boarded a train bound for Covington, Louisiana. He sat in the whites only passenger car. And he was arrested for violating Louisiana separate car act after he refused to move to the colored section.

After his conviction, Homer Plessy filed a petition to Louisiana’s Supreme Court. He did this realizing that at this time in history, Louisiana’s trees sometimes bore strange fruit that had blood on the leaves at the root. Perhaps, his gallantry resulted from the weapons he would arm himself with. Homer Plessy brandised Law as his projectile and justice as his shield. Louisiana Supreme Court would deal a crushing blow. And then the Supreme Court of the United States would also rule against Homer Plessy.

Homer Plessy didn’t lose because his interpretation of the United States Constitution was unsound. Homer Plessy lost because the nation’s commitment to white supremacy was greater than its commitment to the aims of Reconstruction or to the promises of the United States Constitution. The Plessy decision would inspire other rulings that expanded the use of separate but equal. It enshrined white supremacy in the 1898 Louisiana State Constitution. Plessy normalized the belief in the inferiority of people of color. It etched the seal of legality on a system of social degradation. And it instantly reversed the aims of Reconstruction.

In their final report on their efforts to overturn the separate-car act, the citizens’ committee wrote and I quote, “We still believe that we were right and our cause is sacred.” Today, we affirm that belief. We do this out of a dual commitment to restorative justice, which seeks to heal, through acknowledgement, accountability, and engagement, and toward the aims of transitional justice, which seeks to reckon the past and reconstruct the future.

Many years have passed but there is no expiration date on justice. This pardon carries with it the hope that people will leave here and seek greater understanding of how racial hierarchies have been embedded in our society. And begin reconcile the fact that everything branded legal is not just.

In Plessy’s day, a Louisiana official warned that there will be consequences to injustice. He said, “Injustice carries the seeds of defeat and decay. Justice is irrepressible. No matter how you may trample it, its voice is never silent. It clamors with a force that is irresistible. Until at last, its voice will be heard, and the structures whose foundations rest upon its violation will crumble into ruin.” A corroboration of the maxim that, “Nothing is settled until it is settled right.”

Today, this pardon serves to settle right the matter of Homer Plessy, and the question of racial hierarchies in the state of Louisiana. I thank you, and I introduce next Mr. Keith Plessy. He is a descendant of Homer Plessy.

Keith Plessy

Thank you, Professor Bell. Good morning, everybody. I’m Keith Plessy, first cousin three generations removed from Homer Plessy. I thank God and everyone who came out today to witness history in the making.

One hundred and twenty five years ago on January 11th, 1897, Homer Plessy changed his not guilty plea to a guilty plea and paid a $25.00 fine. This is truly a blessed day for the ancestors and the elders, for our generation today, for our children, and for generations that have yet to be born. I feel like my feet are not touching the ground today. Cuz the ancestors are carrying me.

I’ve had this feeling since November 12th, 2021, at 9:22 am, in a Zoom meeting when District Attorney Jason Williams, my partner in history, Phoebe Ferguson, and myself spoke at the hearing for the pardon, for the posthumous pardon, I’m trying to hold back my tears, y’all. As a matter of fact, we had a unanimous decision of a five to zero vote at that pardon, and Senator Edwin Murray wrote the Act number 125, and it received unanimous votes from the House and the Senate. And to the 56th governor of Louisiana, the Honorable John Bell Edwards, I applaud you, sir, for choosing this area, this sacred ground, to sign this full posthumous pardon in honor of my ancestor.

He purchased his ticket not far from this spot, on that area on the front. That is Kyle’s office. And he rode about a block before he was kicked off the train, at a corner that was formally Press and Royal Streets and now is Homer Plessy Way and Royal Street. And I thank you with all my heart on behalf of my family, behalf of the Ferguson family, the Harlan family, my chief. Homer Plessy will have his way today.

And my partner in history, Phoebe Ferguson, is next to speak.

Phoebe Ferguson

Keith is always such a hard act to follow. Uh, good morning, Governor Edwards, honored guests, family, and friends. My name is Phoebe Ferguson, and I am the great-great-granddaughter of Judge John Howard Ferguson. It was Judge Ferguson who ruled against Homer Plessy in 1892 and upheld the validity of the Separate Car Act, which made racial segregation in public transit in Louisiana a crime.

I am also the co-founder of and executive director of the Plessy and Ferguson Foundation. Our mission is to honor the work of Homer Plessy and the Citizens Committee for their courage, commitment, sacrifices, and the decades-long pursuit of justice and equality. Though he could not be be here today, I wanted to specially acknowledge Keith Weldon Medley, co-founder of the Plessy and Ferguson Foundation and author of We As Freemen, Plessy v. Ferguson, the book that first informed and educated us all about the crucial role of the Citizens Committee in this historic effort.

On January 11th, 1897, following the ruling in the US Supreme Court, in Plessy versus Ferguson, Homer Plessy was compelled to plead guilty in Judge Ferguson’s court and was fined. It is this unjust criminal conviction that has brought us here today, not to erase what happened to 125 years ago, but to acknowledge the wrong that was done, and to reaffirm our pledge to do whatever is in our power to prevent such wrongs in the future.

We come here as descendants of both sides of the Plessy versus Ferguson case. In the true spirit of reconciliation, and healing. It is our honor to be joined today by the descendants of the members of the Citizens Committee. We also wish to acknowledge Kate Dillingham, the great-great-granddaughter of the lone dissenting judge, John Marshall Harlan, the Supreme Court Justice John Marshall Holland.

We also would like to acknowledge Avis Brock, the great-great-granddaughter of civil rights leader, Reverend Avery Alexander. We are grateful to the memory of Reverend Avery Alexander, whose courageous work in the civil rights movement of the 20th Century led to the passing of the law sponsored by Senator Murray which provides us with a path to recognize and address the injustices of the past.

We also appreciate the support of the Orleans Parish District Attorney Jason Williams and the Civil Rights Section of the DA’s office led by Miss Emily Maw which greatly assisted us in this effort today. And of course, without the recommendation of the Louisiana Pardon Board, and most importantly, the support of Governor Edwards, none of this would be possible.

I would like to also acknowledge the Plessy and Ferguson Foundation Board, without whom, we would not be where we are today — our co-founders are Keith Walden Medley, Brenda Billup Square, and A. P. Turo, Jr. We hope that the efforts on behalf of Mr. Homer Plessy will help to inspire others who have also been unjustly convicted for opposing racial segregation in the state. The official pardon of Homer Plessy and the recognition of his wrongful conviction and of by the state of Louisiana does not end our work. Rather it inspires us to continue with the effort to educate about our history and to advocate for justice and equality.

We cannot undo the wrongs of the past, but we can and should acknowledge them and learn from them. Thank you.

Good morning. Um, and I’m really happy that they let me play a small part in the ceremony today. Um, just to give you a little background about how and why this bill came to be. I don’t recall which article I read, but I read where some states had passed a bill to say that if you were convicted of crimes trying to undo these Jim Crow laws that you will receive a pardon. And based on the really rich history of civil rights we have in this state, I thought it would be appropriate.

For those of who don’t know, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference was formed at New Zion Baptist Church here in our city. I happen to be a member of that church and was baptized by A. L. Davis, where it was formed. Uh, the Freedom Riders who went across the south were trained in that church and our doors were open to ’em. In fact, you might on any given Sunday morning, you might find Jerome Smith sitting at outside the church because he calls it a shrine to the civil rights movement.

Um, so I filed this bill, and it was it was initially filed to make it mandatory that you’d receive a pardon. Well, shortly after the bill was published, I got several phone calls from civil rights activists who said, Senator, this is a great idea, but we don’t think you should make it mandatory. Some of us really enjoy the fact that we were arrested. We want our kids and grandchildren and family to know that we thought it important enough to put this on the line. So, I changed the statue to make it permissible so that someone wanted to have a pardon that they could apply for it.

So, as the bill was going through the process, I also got the idea that there couldn’t be there was no better person to name this act after other than Reverend Avery C. Alexander who spent his life doing a lot of things to try to get rid of these laws and to improve everything for us. So, that’s why the bill has his name on it. So, and then I guess once the the district attorney and the Pardon Board acted, I had a chance to meet Mr. Plessy and Miss Ferguson, and I promised them at the time that I would get them a signed copy of the act because I didn’t know there was a Foundation, and I had this to present to them today as well.

And there are additional copies for the Foundation because he says that they have they’ve received lots of attention from across America because of the work that was being done and once again, thank you all for your work. Thank you mister DA for putting this forward, and thank you Governor Edwards for signing it. Now, we’ll hear from our honorable district attorney, Jason Rogers Williams.

I see back there, Mary Howe, a friend of good and necessary trouble. Thank you for what you do and thanks for being a visionary. Over a century ago — Please, give her a hand.

Over a century ago, one of my Orleans district attorney predecessors prosecuted Homer Plessy’s brave defiance of the Louisiana Separate Car Act of 1890. Just one of many Jim Crow laws passed by the Louisiana Legislature to codify white supremacy and racial segregation after the Civil War. Homer Plessy died, convicted of this crime. But the legacy of Jim Crow laws lived on for generations. Lived on, that is, until a steady stream of civil disobedience by heroes, standing on the shoulders of leaders like Homer Plessy, risked their lives causing so much good trouble that elected officials were forced to act.

But the legacy of separate but equal still casts a shadow on all of our lives today. That shadow is clearly visible in the gross inequalities we see across this city and across this state and, I say, across this country. It was important that the office had prosecuted Homer Plessy be the office to ask for his name to be pardoned, because we all know that while Homer Plessy’s actions at that time made him guilty of a crime under the law, it was really the law that was the crime.

My predecessor should not have prosecuted Homer Pleasant. Just because a law can be enforced or a person can be prosecuted, does not mean that they should be. Slavery was lawful for 250 years in this country, and enforced by laws in many states, and therefore, one of the greatest crimes against humanity by a government against its people. Not one of those laws should have ever been enforced by any DA anywhere. Leaders today cannot and should not blindly pass or apply laws when the outcome is unjust. immoral, or inhumane.

So, let me tell you today, I did not submit this pardon asking for Homer Plessy to be forgiven. I submitted it asking for us to be forgiven, the institution. The late Archbishop Desmond Tutu said true reconciliation exposes the awfulness, the abuse, the hurt, the truth. It is a risky undertaking, but in the end, it is worthwhile. Because in the end, only an honest confrontation with reality can bring real healing. And although our great country has slow walked its reckoning, the office of the DA will not.

America has never had a process of truth and reconciliation, an honest confrontation with the reality of its oppressive past, and we see the direct consequences of this failure to have an honest conversation so boldly in the criminal legal system. Most notably with the grossly disproportionate not disproportionate criminalization and incarceration of African Americans. And nowhere have these consequences been worse than right here in the city of New Orleans.

The Orleans Parish District Attorney’s Office is now working openly and transparently towards confronting those dire consequences. With policies like no longer sentencing, using sentencing enhancements through their habitual offender law, by no longer prosecuting simple possession of marijuana and other crimes of poverty. But while we seek to correct the sins of the past, we must acknowledge my predecessors roles in committing these sins. If for no other reason than to build the public’s trust in our legal system.

We must reckon with our past. We must confront. We must acknowledge. And we must humbly ask for forgiveness for the role our legal institutions have played in the apartheid that the people of this country have endured. I will not be complicit and disguise the source of our collective sins, and I understand just how far we have to go but we are going to do it together as a people of all hues and all religions and all genders and all walks of life. In the words of Tokien, “Deeds will not be less valiant because they were unpraised.”

Homer Plessy died a convict. Imagine for a moment just what he must have felt 125 years ago. Imagine what his wife must have felt during their lifetime. Let me be clear. Homer Plessy was no criminal. He was then, and he is now a hero. And we will do our part to ensure that history reflects just that. Homer Plessy, Louis Martinette, Albion Tourgée and the Citizens’ Committee, belong to a long line of heroic civil disobedience that Dr. King traced all the way back to the early Christians defying unjust Roman law.

The state of Louisiana prosecuted Homer Plessy to make a point of upholding a racist law. And just as these trains are weighing in and hissing the same way they did when he boarded that train, today we make a very, very different point. We now ask our governor, Gov. John Bell Edwards to pardon Homer Plessy from the stain of immorality on our state’s history. So, let me welcome our friend, friend of New Orleans, friend of justice, our governor, John Bell Edwards.

Thank you and good morning everybody. You know, this setting is so perfect, and the words that have already been spoken are so appropriate. There really isn’t much to add, but that doesn’t mean that I’m going to sit down there and sign that pardon without trying to share some of my thoughts with you.

I do thank all of you for being here today. It it is a beautiful day, and there’s never a bad day to do the right thing, right? Um, but it’s also a great way to kick off the New Year and perhaps a new chapter in the state of Louisiana, and in the country, and Donna and I wish all of you a very Happy New Year, and may 2022 be the best year ever, and if not, may it certainly be better than 2020 and 2021.

Um, thank everyone who’s been so instrumental in making this happen this morning. Uh Professor Bell, Keith, Phoebe, Kate, your family, Senator Murray, the District Attorney Jason Williams, all of you for being here. Uh but for those of you who believe this was the right thing to do and then work to make it happen, it reminds me that faith and works together are what we are called to engage in.

While this pardon has been a long time coming, we can all acknowledge this is a day that should have never had to happen. 130 years ago, Homer Plessy bought a ticket, boarded a train right here where we sit. Bound for Covington, just forty miles to the north, and I know you know the rest of the story, and I’m not going to recite it for you. The subsequent Supreme Court case, as Professor Bell so powerfully described, led to generations of inequity, left a stain on the fabric of our country, and on this state, and on this city, and quite frankly, those consequences are still felt today.

Homer Plessy more than did his part to prevent that stain, and so did many others, and we honor them all today, and their names have been mentioned. I want to highlight today the one eloquent and courageous dissent from Justice John Marshall Harlan, who, I think it should be noted, belong to a family that had enslaved people of color. He initially, though he was a Unionist, he was not in favor emancipation. But his views of race, equality, civil rights, they did change. And his dissent cogently and powerfully made the case that Plessy versus Ferguson was incorrectly decided.

That descent accurately predicted the damage that it would do to our country, and it inspired Brown versus Board of Education, some six decades later. Further, Justice Harlan’s descent demonstrates that justice and decency dictate the absolute necessity that we come together this morning for this posthumous pardon, so that the last chapter in this saga exonerates Homer Plessy and celebrates his cause as right and just.

In his lone descent, Justice Harlan predicted that in time, Plessy would prove every bit as pernicious as Dread Scott, the 1857 Supreme Court case that is universally condemned as the worst decision ever by that court, as it inexplicably held that the United States Constitution did not extend citizenship to people of African descent, whether they were free or slave, no matter when or how they came to be in the United States.

A war was soon fought over the issue. The 13th, the 14th, the 15th Amendments were all added to the constitution to effect change. But neither Homer Plessy nor any other person of color immediately received the benefits of that war and the amendments sought to confer on them. Now, I have to admit ‘pernicious’ is not a word that I use very often — I can see that Justice Harlan’s command of the English language is superior to mine, but the word perfectly fits because it means evil, fatal, ruinous, wicked.

So, I think I’m going to use that word a few more times this morning. and because I cannot possibly do justice in expounding on the righteousness of Homer Plessy’s calls or inadequately illustrating the other wrongfulness of the court’s decision, I will recite a couple of brief passages from Justice Harlan’s eloquent descent. He wrote and I quote,

But in view of the constitution, in the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste here. Our constitution is colorblind, and neither nose nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law. It is therefore to be regretted that this high tribunal, the final expositor of the fundamental law of the land has reached the conclusion that it is competent for a state, [pointing at self — our state] to regulate the enjoyment by citizens of their civil rights solely upon the basis of race.

The destinies of the two races in this country are indissolably linked together and the interest of both required that the common government of of all shall not permit the seeds of race hate to be planted under sanction of law. What can more certainly arouse race hate, what more certainly create and perpetuate a feeling of distrust between the races, than state enactments? Which in fact proceed on the ground that colored citizens are so inferior and degraded that they cannot be allowed to sit in public coaches occupied by white citizens. That as all will admit, is the real meaning of such legislation as was enacted in Louisiana.

Those were Harlan’s words, and he was right. The Supreme Court majority embraced racism and white supremacy as if the 13th and 14th amendments to United States Constitutions were mere ornaments without meaning or effect. Very sadly, it’s not lost on me that one of the seven justices who joined in the majority of the opinion was Louisiana’s own Justice Edward Douglas White. And I’ll point out that much of his work on the court was admirable. But that was not his finest hour.

The cause of the pardon that we gather today to celebrate, unfortunately, isn’t limited to writing a historical wrong. The pernicious effects of Plessy linger still in terms of race relations, equality, and justice. We are not where we should be. And quite frankly, we’re not where we would have been. Had at least four other justices had the same fidelity to the constitution, the first six decades of the 21st century should have been filled with infinitely more promise and progress in race relations, and would have been had slavery immediately given way to equality and freedom.

Instead, the Plessy majority ignored the plain meaning and purpose of the 13th and 14th Amendments and wrongly enshrined segregation into the law for the explicit purpose of declaring and promoting white supremacy. As immoral and factually erroneous as that was and is, the fictitious notion of separate but equal remained with us until the Supreme Court revisited the issue in 1954 in the context of public education and implicitly overruled Plessy.

And in Montgomery, Alabama, one year later in 1955, Rosa Parks, in another very similar courageous act of protest, refused to a bus seat reserved for white passengers. I want you to think about this. That was 63 years after Homer Plessy did that right here. More than six decades, and it was still necessary. because not much had changed, and it hadn’t changed because the Plessy majority said it didn’t need to change.

Plessy also emboldened state legislatures and constitutional conventions to expressly promote white supremacy in a multitude of truly pernicious ways including the 1898 Louisiana Constitutional Convention that sought among other things to negate the voices of black jurors. By allowing criminal convictions for just nine of twelve jurors finding guilt. This wrong was only righted three years ago. by the adoption of a constitutional amendment requiring unanimous juries for criminal convictions in Louisiana.

That the convention delegates were motivated by their zealous desire to perpetuate white supremacy is not debatable. Their writings and speech were memorialized in the official records of the convention. After Plessy, they had no reason to even pretend otherwise. Pernicious.

Sadly, there are other ill effects of Plessy plaguing us still. Individuals have recently been nominated by the President and confirmed by the United States Senate as federal judges with lifetime appointments who cannot or would not stayed on the record in response to direct questioning that Brown versus Board of Education was and remains correctly decided. I can only conclude that those individuals allow for the possibility that Plessy was correctly decided. How sad; it ought to be disqualifying.

The stroke of my pen on this pardon, while momentous, it doesn’t erase generations of pain and discrimination. It doesn’t eradicate all the wrongs wrought by the Plessy Court or fix all of our present challenges. We can all acknowledge we have a long ways to go. But this pardon is a step in the right direction, and I am beyond grateful that I have a small part to play in ensuring that Homer Plessy’s legacy will be entirely defined by the rightness of his cause and undefiled by an unjust criminal conviction. And I pray that we will all commit ourselves to further moving our country forward, loving one another, and recognizing the dignity and equality of all of our brothers and sisters, so that we can become what we aspire to be — one nation, under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all. So, God bless you all.

I am now going to read the pardon that I will sign with 27 pens in just a minute.

Grant of Posthumous Clemency to Homer Adolph Plessy

Pursuant to the Avery C. Alexander Act

TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN

WHEREAS, Homer Plessy, date of birth, March 17th, 1862, and date of death, March 1st, 1925, was convicted of the following offenses, and sentenced as shown:

Orleans Parish, Criminal Court, Section A, on January 11th, 1897. The offense was violating the 1890 Separate Car Act, and he was sentenced to a $25.00 fine.

Whereas the Louisiana Board of Pardons in accordance with Article IV Section 5 of the Louisiana Constitution of 1974, has recommended that I grant a pardon for the above listed offense to Homer A. Plessy.

Now, therefore, I, John Bel Edwards, Governor of the State of Louisiana, recognizing the heroism and patriotism of his unselfish sacrifice to advocate for and to demand equality, and human dignity for all of Louisiana’s citizens, do hereby grant a full posthumous pardon for the above list of offenses to Homer A. Plessy pursuant to the Avery C. Alexander Act of 2006, and do hereby direct you to act accordingly, and for so doing, this shall be your sufficient warrant and authority.

In witness whereof, I have set my hand officially and caused to be affixed the Great Seal of Louisiana in the city of New Orleans on this 5th day of January, 2022.

So, I’m going to ask, I’m going to ask the family members of Mr. Plessy, Judge Ferguson, Judge Harlan to come and stand on the steps behind me while I take a seat and begin signing these pardons. Thank you everyone and that concludes our program. Thank you.

Text prepared by:

- Bruce R. Magee

Source

Grant of Posthumous Clemency to Homer Plessy. Addresses by Angela Allen Bell, et al., Louisiana Public Broadcasting, 5 Jan. 2022, https:// www.youtube. com/ watch?v= ZQN5g4diw0I . Accessed 12 Feb. 2025.