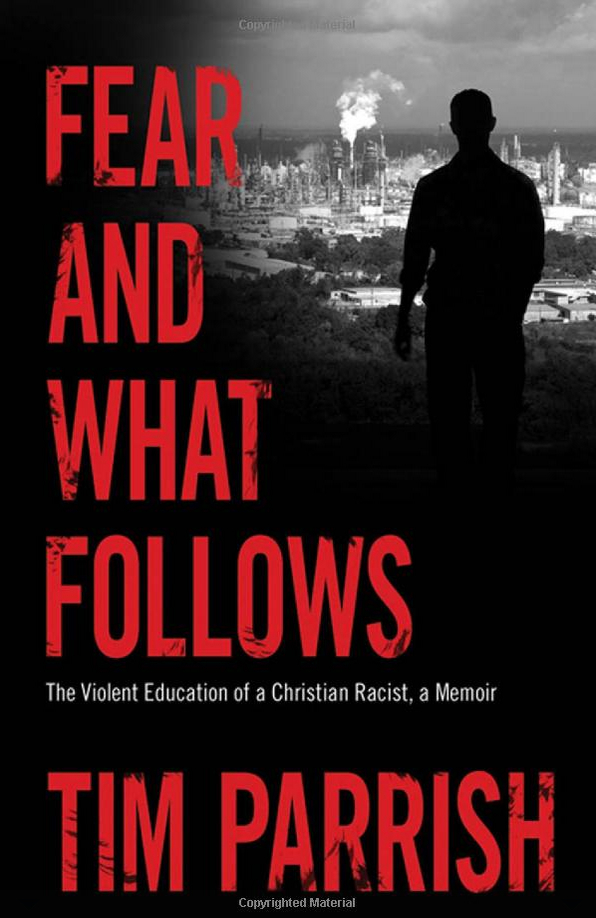

Tim Parrish.

“Southern Men: 1958-1968.”

© Tim Parrish

TParrish@snet.net

Used by permission.

All rights reserved.

Baton Rouge burned at night. Or so it seemed to me. From the top bunk above my brother Olan, I watched the flarestacks at the plants by the river spit flame into a salmon sky. Along the horizon the fat burn-off clouds pulsed pink. My imagination turned it all into the approaching apocalypse our pastor invoked at least every fourth Sunday. Yet I knew the flames were simply part of the neighborhoods two miles away, where my parents had lived when only other whites lived there, the flames part of the plants like the one my daddy worked in thirty miles downriver.

Sometimes hard rains rose into our yard and slipped beneath the front door onto our living room floor. My friends and I waded through the dark oily floods, our parents yelling for us to be careful of drains sucking us down, our eyes scanning for red ants and roaches riding sticks or leaves and ready to land on our legs. People paddled flat-bottomed bateaus down the street. Once, a bass boat motored past sending its wake against our house.

Still, our street seemed a small island in a working-class neighborhood where poverty and abuse lurked but were rarely spoken about. Of course those things existed on our street, too, but my parents tried to protect my two older brothers and me from them. The violence I saw around me was minor, like the fights my friends and I had, wrestling with a few roundhouse punches and handshakes after, fights with reasons and endings. The adults were plant workers, school teachers, state employees, cops, and firemen. We all went to church and loved Jesus a little bit more than we loved LSU football. We stood up for ourselves. We disliked and distrusted blacks.

For a while I didn’t see any contradictions.

My daddy sailed into Nagasaki Bay a month after the bomb, but he only spoke once about being loaded into a truck bed and driven with other sailors through the flattened wasteland of rubble and dazed Japanese. I think he didn’t like the sadness and vulnerability telling that exposed. What he liked to tell was the part about two Japanese men rowing up in a small boat and pointing a tiny cannon at his destroyer. “We yelled and waved our arms at ’em to go on till they went,” he said in his baritone drawl, his storyteller’s smirk on his face. “They rowed on over to a big old carrier and then a battleship and all over all day, pointing that itty bitty cannon, till they just give up and went on back to shore.” As with most of his stories, he delivered this one with irony that provided some distance from the dismal futility and instead focused on the laughable absurdity. But no matter what the subject matter or tone, darkness and conflicted emotions from whatever source-fatigue from plant work; worry over providing for us; his moodiness; Christian guilt-often underpinned his telling. When the darkness lightened, though, he laughed hard at his own stories. That was when I felt most strongly how much he loved us.

He told stories about toughness, courage, revenge, character, and defiance: the story of loosening the band on an insufferable supervisor’s hard hat so that when he plopped it on his head it dropped over his eyes; the story of Daddy popping his own kneecap back into place during a high school football game; the story of a cloud of phosgene gas knocking a man at the chemical plant to his knees, and Daddy and another operator grabbing him up and saving his life. But my favorite stories were from the war, like his first day in chow line on a new ship. He had been stationed on Midway and was dressed in a non-standard camouflage uniform when the server refused to give him any potatoes. “Feller kept on smartassing me how I wasn’t gone get none, so I just reached over and grabbed his collar and snatched him across that counter. I said, ‘Boy, you best give me some taters fore I whup your ass.’” Daddy laughed and held his flat belly. “He started going, ‘Yes, sir, yes sir,’ and give me a big old heap. Word went around I was some kinda commando cause of them camouflage clothes and after that I got all the taters I wanted.”

Daddy had grown up on a Depression-era farm in Mississippi, the son of a stern man who used a razor strop on his boys whenever they “gave him nonsense.” His skin was dark from years of work in the sun and from the Cherokee blood in his background. He was thin with sinewy arms, high cheek bones, black hair and brown eyes that glinted with intensity or mischief. When he thought we needed it, he took the belt to our behinds, but what was truly painful were his unreadable sternness and unclear expectations.

When I was too young to realize, he switched us to a country church twenty miles outside of town because the Southern Baptist pastor in the church two blocks from our house suggested that the congregation take a vote on whether blacks should be allowed to attend. No blacks lived within a couple of miles of our church, and none would have tried to come, but just the consideration drove Daddy away. If work allowed, he went to church three times a week. He returned thanks to Jesus before every meal, read the Bible often and demanded we be good Christians. But he worried about “niggers taking our neighborhood” and said followers of Baton Rouge’s future SNCC leader, H. Rap Brown, should be shot dead in the street. When footage of blacks being bitten by dogs and hosed and beaten by police came on TV, his rage heated the room almost as if he were inflicting the punishment. Worst of all, although I wouldn’t think it until much later, he was something close to glad when the Kennedys were assassinated and said of Martin Luther King that he was faking his death and would rise in three days as the new black Christ. It seemed clear where I should stand.

Then he would tell the story about his train trip home from the war, one of the stories that didn’t often emerge from his repertoire. His journey from the Pacific had brought him back to California, and from there he and thousands of other returning servicemen were loaded onto a giant train that would travel for days across the southwest, Texas, Louisiana and on, dropping Daddy and the other Mississippians not far from home. The lightness and joy fell away when he told this story, his voice growing serious. “We heard they’s beating Jews and niggers at the other end of the train-this was a long train-but we hadn’t seen none of that in our cars. About the third day these nigger boys showed up in our car where they wasn’t supposed to be and they was scared to death. They was going, ‘They’s beatin’ people bad back there and they’s workin’ their way down heah.’” Daddy’s impersonation was exaggerated. “They was four of ’em, just old farm hands from Mississippi like us, so we put ’em up in our bunks, even let ’em sleep in there with us, head to foot while these sonsabitches kept going up and down the aisle all night asking if we’d seen any niggers. When we got to Jackson, them boys got off and they was going, ‘Thank you, sirs, thank you, thank you.’ They knew how to act.”

Even very young I knew there was something wrong about American soldiers being attacked by other American soldiers, but my confusion over why Daddy would protect these black men was still only a hum in my subconscious. It was this contradiction between being a tolerant Christian man and a man with an urge toward race violence that would eventually be my struggle.

Alan, my oldest brother by nine years, started a riot during a basketball game in the paper mill town of Bogalusa. We weren’t there, but Alan’s teammates confirmed his story. Alan had been a chubby kid who shot up to be a six-foot five, two-twenty menace on the basketball court. He wasn’t a good player until he got out of high school, but he could rough up just about any other big man and terrorize opponents as a rebounder. Even with limited minutes, he often fouled out, which didn’t seem to bother him. In Bogalusa, Alan was getting ready to shoot a free throw when an opposing guard clapped his hands behind Alan’s head. He spun and decked him. Other opponents charged Alan, but as soon as they came within reach of his long arms, he poled them too. Then the fans attacked. “They were running toward us in their street shoes,” Alan said, “but when they tried to stop they started sliding and we busted their asses.” The packed gym continued to rush Alan, his street-tough teammates, and their former Golden Gloves coach, so the Istrouma team clustered together like a Roman war turtle, lashing out as they moved toward the locker room. “I finally rared back and this hand grabbed my wrist. I went to hit him with my other fist and it was this big state trooper who said, ‘Get in that locker room, son.’ The amazing thing is we went in and started wiping off all this blood and none of it was ours.”

As the oldest, Alan had caught the brunt of Daddy’s moods and discipline during the lean days of unsteady employment or working two jobs. Even though Alan was ultra-conservative and ultra-successful academically, he still rebelled. He had a need to prove himself smarter than everyone else, and he studied extra to show up his teachers. Once in junior high, our parents were called to the principal’s office to meet with a veteran history teacher who started crying during their meeting. “I don’t know what to do,” she said. “He’s smarter than me and he humiliates me in every class.” Alan got Daddy’s belt for that, but it didn’t faze him.

One night when Alan was in high school, he came home after curfew. Olan, who was two years behind Alan yet seemed much younger, and I were in our bunk beds and heard Daddy meet him at the front door. “What I tell you about being late?” Daddy said. Alan began to try to explain, but Daddy told him he didn’t want to hear it. I leaned over the edge of my bunk to see Olan’s grinning face. “He’s gonna get it,” he said gleefully. We heard the whack of the belt, Alan’s yelp, and footsteps as Daddy chased him. They careened into our room from the short hallway, then into the kitchen, back into the living room, down the hall and into our room again. Olan and I were both propped up, laughing. Daddy stopped and shook the belt at us. “Y’all want some of this?” “No, sir,” we said and lay flat, still giggling. We reveled in Alan’s misery because Daddy’s anger had filtered through Alan down to Olan. Alan bullied Olan, sometimes forcing him and his friends to box each other in the front yard or else be bloodied by Alan. Olan thought that Alan condescended to him, too, and I agreed, taking Olan’s side in all things.

Mostly, Alan turned his feelings and his energy toward overachieving in academics and school politics. He laughed easily and was nice and supportive in the ways he could be when he was so preoccupied. But I always felt bossed around and impatient when he tried to help me with my math homework or told me to shine his shoes for a quarter or wash and wax his car for a dollar and gave me strict instructions on how to do it then made me redo it. Nonetheless, Alan wanted to protect me, yet even in those efforts his message was jumbled and complicated.

For class in third grade, I’d put together a Revolutionary War battle scene on a snowy field made of flour. That morning Momma had driven me to school to make sure the wind didn’t blow the snow in the wooden box and coat my soldiers in white, but that afternoon she was at work at J.C. Penney’s. I walked with my friends across the large playground, carrying the diorama like a cigarette girl’s tray, the low-sided box Daddy had built unwieldy no matter how I held it. At the corner stood a big, red-headed, sixth-grade patrol boy, his white belt diagonal across his chest like a bandolier, his flag held like a rifle on his shoulder. He stopped us with the flag and sneered. “Aw, he’s got his little men.” He lowered the tip of the flag beneath the edge of the box and flipped it. The flour exploded upward into my face. I bent at the waist, coughing, and shook my head, dropped the box and brushed at my eyes until I could see. I was white all the way down my front. The kid doubled over laughing. My friends glanced between the patrol boy and me. Normally they would’ve laughed, but I think they were stunned that this big kid we didn’t even know, and a patrol boy no less, had done this. I thought for a second about going after him, but his size scared me. I knelt, collected my plastic soldiers from the ground and piled them into the box. The patrol boy stepped into the street, his face bright red from laughter, and gestured with his head for us to cross.

When I walked into the house, I caught sight of myself in the mirror Momma had hung on the living room wall. I looked like a white raccoon, my head coated except for where I’d brushed the flour from my eyes. It was exactly the kind of slapstick that Olan and I loved from the Three Stooges, and even though it struck me as funny, I looked away. “What happened to you?” Alan said from the kitchen table. My ears heated. I didn’t want to tell him what had happened since I hadn’t fought back. Then I imagined the kid’s face if Alan strode up, a high school senior towering over the red-headed punk. “The patrol boy knocked this box in my face.”

Alan shoved out of his chair. He grabbed a rag from the kitchen counter and nudged me toward the door. “Let’s go.”

“I want to clean my — ”

“No, he’s gonna clean it. Put that box and your book sack down.”

We didn’t speak as we tromped the short block to school, his hand lightly on my back, both comforting me and pushing me along. My cheeks were so hot it felt as if the flour might bake, but I didn’t say anything. When we were about fifteen yards away, the patrol boy’s flag drooped to the ground. Alan moved up close and placed me between him and the kid. “You do this to my brother?”

“Yes, sir,” the patrol boy said, his voice shaky.

Alan produced the kitchen rag and held it out. “Wipe it off.”

“Sir?”

“Wipe it off.” I cringed then looked down when I caught the terror and embarrassment in the kid’s eyes. He took the rag and hesitated. “Wipe it.” He gently cleaned my forehead, my eyes, my cheeks, my neck, then brushed at my shirt. My skin shrank from him. “That’s enough,” Alan finally said, and the kid’s hand fell to his side. “I oughta do something like this to you,” Alan said. “Would you like that?”

“No, sir.”

“I’ll bet you wouldn’t. Listen here, if you do anything like this to him again, I will do something.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Now tell him you’re sorry. Look at him, Timmy.” Alan laid his hands on my shoulders. I forced myself to meet the kid’s eyes, teary and squinched.

“I’m sorry,” he said.

“Good,” Alan said and took the rag back. “Let’s go home.”

The short block back to the house seemed like a mile. Alan’s long legs stretched so that I had to stretch to keep up. He draped his arm around my shoulders. “You got to learn to take up for yourself,” he said. “You can tell me if it’s somebody who’s not your size, but you still got to take care of yourself. You understand?”

I nodded. I was glad that Alan had taken up for me but furious that both the kid and I had been humiliated. What I understood was that no matter what the size of the bully, if I didn’t fight back, I was weak and cowardly.

Olan wanted to be a cop from the time he was a little kid. Later, he would have as reasons the desire for power and for approval from Daddy, but as a kid the reason came from the TV channel Times, Tunes and Cartoons, which provided exactly what it promised. One night while he was watching, a bulletin went out for all Baton Rouge Police to report to duty immediately because, as Olan remembers, a flying saucer had landed. It turned out the saucer was actually a chemical plant pop-off valve that had been blown a number of blocks into someone’s yard when the pressure in a pipe had gotten too high, but what had actually happened didn’t matter to Olan. All that mattered was the men with badges and uniforms were the first called to the most exciting event on Earth.

Olan lived in Alan’s shadow. When he arrived for classes taught by the same teachers Alan had two years before, they would ask if he was like his brother. Olan didn’t know if they meant the brilliant student or the troublemaking bully. Either way he didn’t want to be like him, so he didn’t know what to say, something that must have made him feel invisible. At school he was a shy, skinny kid who wore thick black-rimmed glasses to correct his terrible eyesight and who wrote with his left hand, something that made his intelligence suspect in the late fifties and the sixties. His grades were average.

Despite Olan’s being seven years older than I was, we were allied in all things. On Saturday mornings we got up early together, poured bowls of Cheerios and watched The Three Stooges. When they were replaced by the Mickey Mouse Club, he created a petition that expressed our hatred of Mickey and the Mousketeers and our strong desire to have the Stooges reinstated. He enlisted some of his friends and me to sign it, but he also forged a number of signatures in his scrawly hand before he sent it off simply to “Walt Disney Company, Hollywood, California.” Several weeks went by, and one day while Olan, Momma and I were visiting our relatives just north of town, the phone rang. “Rachel, it’s Hollis,” Aunt Evelyn said. Momma took the phone, raised her eyebrows and lifted her hand to her throat as she listened. “All right, we’ll come right on home.” She hung up and looked at Olan. “Your daddy says there are some men at our house from Walt Disney.”

Olan glanced at me, his face stricken. I gave him a congratulatory nod. “They’re at the house? With Daddy?”

She nodded. “Did you write some kind of letter?”

Olan didn’t say much during the drive, but I was exultant. We’d defied the intrusion of the saccharine Mouse Clubbers and had forced a show down with the company. Olan and Momma didn’t appear to share my enthusiasm.

Olan trudged from the car to the living room, and Daddy met him with an executioner’s grimace. Two men in suits stood from the couch as we came in. “This is Gordon Ogden,” Daddy said. “He owns the Gordon Theatre. This man is a lawyer from the Walt Disney Company. They tell me you wrote a letter and some kind of petition.” I stepped up close behind Olan, hoping he would tell them off, demand that justice be done, even though Daddy’s scowl and the bizarreness of Disney men in suits visiting our house were straightening my spine.

“Yes, sir,” Olan said.

Mr. Ogden smiled. “We’d like to talk to you.”

Daddy gave Olan a look that told him he was going to get it for pulling a stunt like this. We all sat down to talk as if Olan actually posed some threat to the Mousketeers. “Tell us exactly what your complaint is,” Mr. Ogden said. Olan cleared his throat, adjusted his glasses, then in a shaky voice laid out the silliness of the Mouse show and the virtues of the Stooges. I was impressed at his honesty in the presence of Daddy’s simmer and the unknown retribution of a lawyer and movie theatre owner, and I nodded along until Daddy gave me a look too. The two men listened without much expression until Olan finished. They exchanged smirks.

Mr. Ogden leaned forward. “Olan, we think the Micky Mouse Show is a fine show. We believe the Mouseketeers are exactly the sort of wholesome young people America needs as examples. The reason we’re here is that we hope that you’ll give the show a chance.”

“We admire your get-up-and-go,” the lawyer said, “though we’re disappointed that it seems you faked most of the names on the petition.” He paused. Olan didn’t look at Daddy, but we could all feel the heat coming off of him, could anticipate the skinny belt coming out of its loops. “That said, we would like you to work for us at the theatre this summer. Until then, we’re willing to pay you to watch the Mousketeers and write a brief summary of the show and the commercials. All you have to do is send it to us on these stamped envelopes we’ll give you.”

Mr. Ogden smiled. “We think you’ll see what a fine organization the Disney family is.”

Daddy glared at Olan. “Yes, sir,” Olan said, and took the envelopes from the lawyer.

Everyone stood. “Do you like the Mickey Mouse Show?” he asked me. Daddy cleared his throat.

“Yes, sir,” I said. The lawyer reached into his brief case, brought out some large red, blue and yellow pieces of plastic. “We’d like you to have these,” he said, and handed them to me. Stencils of Donald Duck, Goofy, and the hated Mouse himself. Mr. Gordon and the lawyer shook everybody’s hand, including mine, told us he’d be in touch about the job, and left.

“You do anything like that again,” Daddy said to Olan, “I’ll tan your hide.” He pointed at me. “Yours too.” We nodded and went to our room. Olan plopped onto his bottom bunk, tossed the envelopes to the side and stretched out.

“These are crummy,” I said and threw the stencils across the room.

“So what? I got a job at the movies and I get paid to act like I’m watching that stupid mouse.” He grinned. I stared. Had we won? If Olan said it, we must have, so how come I didn’t know? I went and picked up the stencils and stared at them again. They still seemed crummy.

Like Alan, Olan didn’t excel at school sports, but he was determined that I was going to be a great player like LSU’s Heisman winner, Billy Cannon, who had gone to our high school. By the time I was three, Olan was tossing me passes in the back yard. By the time I was seven, I was running patterns and making difficult catches, ducking beneath the lopsided, circular clothesline, button-hooking just before the ball hit my stomach. The most difficult route was a fifteen yarder from one end of the yard to the other. I would run hard on a line, then cut behind the pin oak just as he hurled the ball. Behind the tree I would lose sight of the ball, but because Olan was accurate, I knew where it would be in the air when I cleared the tree. He taught me to never take my eyes off the ball and I would keep going full blast toward the corner choked with snapped bamboo saplings and torn vines, would jump and flatten out, the ball dropping into my outstretched hands as I landed and rolled through the foliage and up against the chain-link fence. I’d toss the ball back to him and we’d do it over and over for hours, me in my Houston Oilers’ Billy Cannon helmet, he in his Johnny Unitas Baltimore Colts’. He never criticized me, always encouraged me and taught me as he molded me. He gave me a confidence and arrogance as a ball player that most kids around me didn’t have, as well as a toughness that kept me going half a season with a badly-swollen knee and all the way through a championship game the day after I’d literally split my nose down the center and blackened both my eyes running into the edge of a brick wall. I thought of myself as special, nearly invincible.

But what may have bonded us most was our shared love of Christ and his promise of salvation and acceptance. We didn’t talk about it, but I saw the seriousness Olan carried into church, saw him publicly rededicate his life to Christ several times when he felt he’d sinned or, I suppose, felt lost and unprotected. No matter what Olan did or how he thought he’d failed, Christ was there to forgive without criticism. We saw Christ as pure and unchanging, saw baptism as a way of literally washing away our sins and restoring perfection. Olan believed so strongly that when he felt he’d failed Jesus, he asked to be baptized a second time. I think his devotion to Christ was also the only way he believed he could please Daddy, and it made him feel closer to Momma, who tried harder to live a life of forgiveness than anyone else I knew.

And yet I saw Olan wrestling to resolve Jesus’s message with our church’s warlike lust for the end times, their constant focus on both our unworthiness and the nearly inevitable fate of eternal hellfire, and their us-against-them condemnation of not only blacks but of everyone who didn’t believe what we believed, a list that included Catholics (pagan idolators), Muslims (heathens), Communists (godless heathens), and Episcopalians (Catholic light). Olan’s desire to make Daddy proud would make his rebellion against the church all the more painful for him and confusing for me.

The messages about how to behave and what to believe may have been confused, but on April 2nd, 1966, one thing became clear — the war against blacks was real. That night, Olan and I thumped the paper football back and forth across the kitchen table, Olan keeping score on a wrinkled piece of paper. The score often went over a hundred since we played until our index fingers wore out or Momma made us stop because we yelled too much.

An explosion in the distance slightly vibrated our windows. We froze. Alan clomped down the short hall, then we sprang up and joined him and Momma in a circle in the living room. “Esso?” Momma asked. Daddy was at work thirty miles away at Wyandotte Chemicals, but any plant explosion sent anxiety through us because we knew men at all of them. The three of them gave each other concerned glances, but I felt mostly excitement. Alan pushed through the front door and we went in a cluster into the yard. We peered toward the river and the plants, where the sky was no brighter with fire than usual.

“The Russians?” Olan asked.

Alan sneered. “You see a mushroom cloud, stupid?”

“It’s night time.”

“You can see a nuclear bomb at night.”

“How you know?”

“I know, dummy.”

“Shut up,” Olan said.

“You shut up,” Alan said.

“Boys,” Momma said, still staring off, her knuckles pressed to her lips.

Next door Mr. and Mrs. Goudeau and their five daughters spread out onto the driveway.

“What y’all think it is?” Momma asked them.

“Got to be a plant,” Mr. Goudeau said in his thick Cajun accent.

“Times, Tunes and Cartoons will say,” Olan said, disgust at Alan still in his voice.

Olan spun, stomped to the house and slammed the door behind him. I thought of joining him in a show of solidarity, but there was too much going on outside.

“It wouldn’t be Cuba, would it?” Momma asked.

“There’s no mushroom cloud!” Alan said. He crossed his arms, adjusted his glasses and looked straight up between the canopies of trees in our front yard. The night hung quiet except for police sirens now whooping. I thought of walking the few steps over and talking to Sherry and the other Goudeau girls but stayed next to Momma. I wished Daddy were there, pointing out satellites like he sometimes did, stars that moved across the sky and didn’t twinkle like real stars.

The air and ground jolted. We crouched. The sound rolled around on us before travelling along and dying like thunder. Olan crashed through the door and back outside to join us. We peered away from the river now. “Howell Park,” Alan said. I pictured the old jet fighter we could climb on near the pool and wondered if it had somehow blown up. Our other next door neighbor tore from his house in his police uniform, still buckling his gun belt. Momma called to him what was going on, but he jumped into his car and screeched off without answering.

“The windows almost busted out,” Olan said.

“They musta blown up the pool,” Alan said, his lips a dazed half-smile. “I heard Mr. Bowman say they might.” Mr. Bowman was the local Boy Scout leader, and, although I didn’t know it yet, the head of the local Klan.

“He did?” Momma said.

“Yep.”

“The swimming pool?” I asked. Nobody said anything.

The next morning Daddy came from work wearing a bemused smirk, newspaper in hand. He kissed Momma and sat at the kitchen table with her and me. Alan and Olan walked in, Alan buttoning his shirt, Olan holding a toothbrush. “They blew up the building at Howell and tried to blow up Webb,” Daddy said. “I figured it’d happen once they let the niggers in. I heard some of them Klan fools at the Boy Scout meeting say something last week.”

“I told y’all,” Alan said.

Daddy frowned and pointed. “Don’t nobody say a word about that to nobody. Y’all go on get ready for school.”

“I wanta go see,” Olan said.

“Y’all get dressed,” Momma said.

Alan and Olan slumped and trudged off. Momma poured Daddy a cup of coffee and went over to scramble eggs and fry patty sausage.

The Baton Rouge Recreation and Park Commission had closed the city pools two years before, right around the time the federal government had ordered them to be integrated. The previous week BREC had voted to reopen them, but I hadn’t gotten excited about returning. Daddy had made it clear that none of us would be going.

“Was it loud?” Daddy asked, glancing at Momma and me.

“We heard both of them,” Momma said. “We were in the yard when we heard Howell Park.”

“What’d you think, Timmy?”

“I thought that jet blew up.”

Daddy chuckled and sipped his coffee. “I know a old boy who works over there. Maybe we’ll go look at it after school. You wanta go, Momma?”

“I don’t think so.” Before the pool closed, she and I had often gone during summers, and she had talked more about being sad when it closed, and not outraged like Daddy. She came over and scooped eggs onto his plate. He set the newspaper at her place and tapped the article on the front page. She sat down and stared at the words with her hands in her lap.

“They ought not even fix it,” Daddy said. “Federal government’ll probably come in here and charge us extra.”

Daddy may have known an old boy, but the police had the park cordoned off for two days. Howell was a half mile from our house, yet when we were finally able to go, the drive seemed as far away as Mississippi. We turned onto the lane that ran between the oak shaded playground and the public golf course clubhouse. The red brick dressing room for the pool lay a ways from us, but the damage was obvious, half the building collapsed to a pile. For the past two days I had imagined the pool itself having had all of its water blown out like cartoon water and not the destruction of the pool house. I had trouble comprehending it.

“They used some dynamite,” Daddy said. We parked with a handful of other cars and stepped out to join the several oglers. A policeman stood talking to some people and I followed Daddy over to him while my brothers went up close to the rope that kept people away from the scene. Daddy walked up close to the big cop, who stood on the other side of the rope. “Y’all making sure nobody sneaks in for a dip?” Daddy asked. The cop harumphed. “They done a number on it, didn’t they,” Daddy said.

“Looks like it,” the cop said.

“They shoulda known it’d happen when they let ’em in.”

“I spose.” He looked Daddy up and down. “Didn’t catch you by surprise?”

Daddy’s expression went flat. “I was out working.” He turned and walked away. “Smart aleck,” he said.

We went over next to Alan, Olan and some others who were gawking. “Pickaninnies won’t be swimming here a while,” a woman said to us.

“Too bad they did it at night,” the man with her said.

Daddy shook his head and whistled. “Maybe this’ll put a stop to some of this integration nonsense. Better off this way.”

Alan pointed at the exposed lockers, benches and bricks heaped and scattered before us, explaining to a disinterested Olan how the dynamite had worked. In my mind I tried to put it all back together. Many a time I had changed into my bathing suit and showered off the chlorine water here. The shallow foot wash at the exit to the building always had colder water than the pool, and I enjoyed the tingle it gave my feet before and after I swam. I wondered if it had survived.

I strolled a little away from my daddy and brothers so I could see past the debris to the pool, large and sky blue. I’d missed swimming there. I’d liked not only the chilly water but also the energy of so many people and how my mother relaxed when she sunned in a lounge chair. I curled my fingers through the chain link fence. The pool was still blue, but drained of water. I remembered doing cannonballs off the low board, dunking my friends, screaming without a thought. All that was gone, taken by the niggers, I thought, blown apart because of the niggers.

Text prepared by

- Bruce R. Magee

Source

Parrish, Tim. “Southern Men: 1958-1968.” Ninth Letter Arts & Literary Journal 7.1 (2010). Print. Adapted from Fear and What Follows: The Violent Education of a Christian Racist, a Memoir. Jackson: U of Mississippi, 2013. Print. Used by permission. All rights reserved.