Captain Willard Glazier.

“Peculiarities of New Orleans.”

PREFACE.

It has occurred to the author very often that a volume presenting the peculiar features, favorite resorts and distinguishing characteristics, of the leading cities of America, would prove of interest to thousands who could, at best, see them only in imagination, and to others, who, having visited them, would like to compare notes with one who has made their peculiarities a study for many years.

A residence in more than a hundred cities, including nearly all that are introduced in this work, leads me to feel that I shall succeed in my purpose of giving to the public a book, without the necessity of marching in slow and solemn procession before my readers a monumental array of time-honored statistics; on the contrary, it will be my aim, in the following pages, to talk of cities as I have seen and found them in my walks, from day to day, with but slight reference to their origin and past history.

WILLARD GLAZIER.

22 Jay Street,

Albany, September 24, 1883.

CHAPTER XX.

NEW ORLEANS.

Locality of New Orleans. — The Mississippi. — The Old and the New. — Ceded to Spain. — Creole Part in the American Revolution. — Retransferred to France. — Purchased by the United States. — Creole Discontent. — Battle of New Orleans. — Increase of Population. — The Levee. — Shipping. — Public Buildings, Churches, Hospitals, Hotels and Places of Amusement. — Streets. — Suburbs. — Public Squares and Parks. — Places of Historic Interest. — Cemeteries. — French Market. — Mardi-gras. — Climate and Productions. — New Orleans during the Rebellion. — Chief Cotton Mart of the World. — Exports. — Imports. — Future Prosperity of the City.

AS the traveler proceeds down the Mississippi, from its source to its mouth, a unique phenomenon strikes his attention. The river seems to grow higher as he descends. The bluffs, which on one side or the other rise prominently along its banks in its upper waters, grow less bold, and finally disappear as he progresses southward. And if it should be the season of high water, he will find himself, as he nears New Orleans, gliding down a river which is higher than its bordering land, and which is restrained in its penchant for destruction, by massive dykes, or levees, as they are termed in this section.

New Orleans, the commercial metropolis of Louisiana, known as the “Crescent City,” is situated on the eastern, or, more correctly speaking, the northern bank of the Mississippi River, which here, after running northward several miles, takes a turn to the eastward. Originally built in the form of a crescent, around this bend in the river, it has at the present time extended itself so far up stream that its shore line is now more in the shape of a letter S. It is one hundred and twelve miles from the mouth of the Mississippi, 1,200 miles south of St. Louis, and 1,438 miles southwest of Washington. The city limits embrace an area of nearly 150 square miles, but the city proper is a little more than twelve miles long and three miles wide. It is built on alluvial soil, the ground falling off toward Lake Pontchartrain, which is five miles distant to the northward, so that portions of the city are four feet lower than the high water level of the river. The city is protected from inundation by a levee, twenty-six miles in length, fifteen feet wide and fourteen feet high. The streets are drained into canals, from which the water is raised by means of steam pumps, with a daily capacity of 42,000,000 gallons, which elevates it sufficiently to carry it off to Lake Pontchartrain.

The geological history of this section of the country is extremely interesting. The whole region south of New Orleans is made land, having been brought down from the Rocky Mountains and the western plains, by that tireless builder, the Mississippi, which has heaped it up, grain by grain, probably changing the entire course of its lower waters in doing so, filling up old channels and wearing itself new ones, until it finally extends its delta, like an outstretched hand, far out into the waters of the Gulf of Mexico. The river has a history and a romance, all its own, beginning with the time when French and Spanish, alike, were searching for the “Hidden River”— that mysterious stream which, according to Indian tradition, “flowed to the land from which the sweet winds of the southwest brought them health and happiness, and where there was neither snow nor ice,” and which was known by so many different names — and ending with the construction of the gigantic jetties, which have given depth and permanence to the channels of its delta.

The visitor finds the city very unlike northern towns with which he has been familiar. To the Creole quarter especially there is a foreign look, which is intensified by the frequent sound of foreign speech. It is as if one had stepped into some old-world town, and left America, with its newness and its harshness of speech, far behind. But it is not so far away, either. It is only around the corner, or, at best, a few squares off. New Orleans of the nineteenth century jostles New Orleans of the eighteenth on every hand. It has seized upon the old streets, with their quaint French and Spanish names, and carried them to an extent never dreamed of by those who originally planned them. It has reared modern structures beside those hoary with age, and set down the post common school building and the heretical Protestant church beside the venerable convent and the solemn cathedral.

The main streets describe a curve, running parallel to the river, and present an unbroken line from the upper to the lower limits of the city, a distance of about twelve miles. The cross streets run for the most part at right angles from the Mississippi River, with greater regularity than might be expected from the curved outline of the river banks. Many of the streets are well paved, and some of them are shelled; but many are unpaved, and, from the nature of the soil, exceedingly muddy in wet weather, and intolerably dusty in dry. The city is surrounded by cypress swamps, and its locality and environments render it very unhealthy, especially during the summer season. Yet, notwithstanding its insalubrity, it is constantly increasing in population and business importance. Certain sanitary precautions, adopted in later years, have somewhat improved its condition.

New Orleans has a history extending further back than that of most southern towns. While others were making their first feeble struggles for existence with their treacherous foes, the red-skins, New Orleans was stirred by discontent and insurrection. In 1690, d’Iberville, in the name of France, founded the province of Louisiana, and Old Biloxi, at the mouth of the Lost River, as the Mississippi was still termed, was made the capital. The choice of site proved a disastrous one, and the seat of government was moved to New Biloxi, further up the river. Meantime, Bienville, his younger brother, laid out a little parallelogram of streets and ditches on a crescent-shaped shore of the river, in the midst of cypress swamps and willow jungles. A colony of fifty persons, many of them galley slaves, formed this new settlement. Houses were built, a fort added, and the little town received its present name, in honor of the Regent of France, the Duke of Orleans. In the same year John Law sent eight hundred men from La Rochelle. They had no sooner landed than they scattered to the four winds, a number of Germans among them alone remaining in or near the promised city. Amid many discouragements the town prospered, and when, one after another, three cargoes of women were sent out from the old country, to furnish wives for the new settlers, their content was complete. Thus many of the proudest aristocrats of New Orleans trace their descent from these “Filles de Casette,” as they were called, each one being endowed with a small chest of property.

Here the French Creoles were born, and lived a wild, unrestrained life, valorous but uneducated, and became such men and women as one would expect to find in a military outpost so far from the civilized world. For sixty-three years the little colony struggled for life, enduring floods and famines, and the terrors of Indian warfare, when, in 1762, the province of Louisiana was transferred by an unprincipled king to Spain. The news did not reach the remote American settlement until 1764. It was hardly to be expected that a colony so separated by time and distance from the mother country should be intensely loyal, but the people felt themselves to be French and French only, and they resented this unwitting transfer of their allegiance as an unendurable grievance.

The Spanish Governor, Ulloa, did not land in New Orleans until two years later; and though he showed himself to be a man of great discretion, and inclined to adopt a conciliatory policy, the people made the little town so hot for him, that in two more years he was glad to return to Spain. They sent a memorial after him, which, being a most unique document, is worth recording, in substance. Says a recent historian, Mr. George W. Cable: —

“It enumerated real wrongs, for which France and Spain, but not Ulloa, were to blame. Again, with these it mingled such charges against the banished Governor as — that he had a chapel in his own house; that he absented himself from the French churches; that he inclosed a fourth of the public common to pasture his private horses; that he sent to Havana for a wet nurse; that he ordered the abandonment of a brick-yard near the town, on account of its pools of putrid water; that he removed leprous children from the town to the inhospitable settlement at the mouth of the river; that he forbade the public whipping of slaves in the town; that masters had to go six miles to get a negro flogged; that he had landed in New Orleans during a thunder and rain storm, and under other ill omens; that he claimed to be king of the colony; that he offended the people with evidences of sordid avarice; and that he added to these crimes — as the text has it — ‘many others, equally just and terrible!’”

In 1769 the colony was in open revolt, and was considering the project of forming a republic. But the arrival of a Spanish fleet of twenty-four sail checked their aspirations towards independence, and paralyzed their efforts, and they yielded without a struggle.

In 1768 New Orleans was a town of 3,200 persons, a third of whom were black slaves. After the establishment of Spanish rule, although the population was thoroughly Creole, and opposed to the presence of English traders, the government at first winked at their appearance, and finally openly tolerated them, so that English boats supplied the planters with goods and slaves, and English warehouses moored upon the river opposite the town disposed of merchandise.

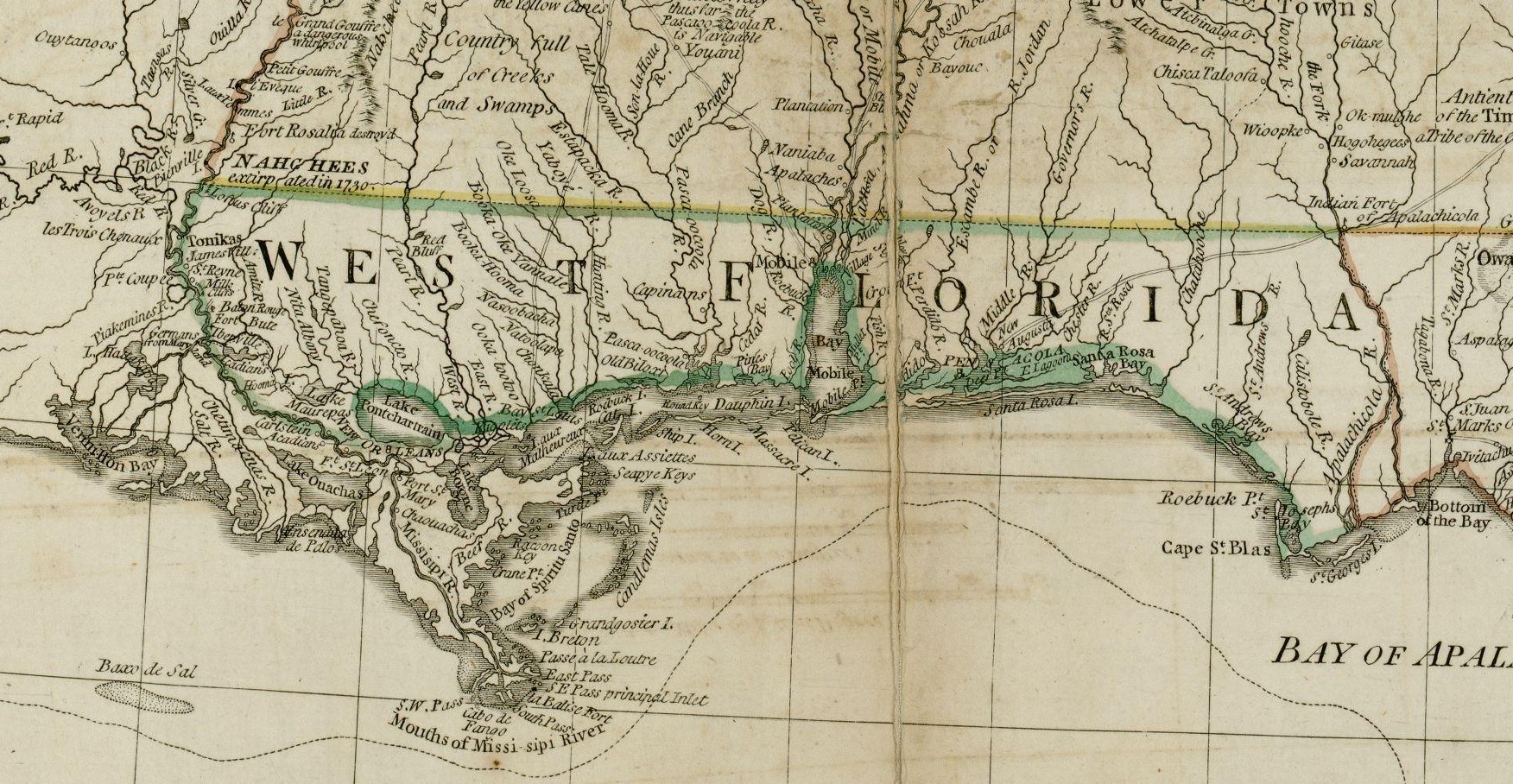

In 1776, at the breaking out of the American Revolution, the Creole and Anglo-American came into active relations with each other, a relation which has since qualified every public question in Louisiana. The British traders were suddenly cut off from communication, and French merchants commanded the trade of the Mississippi. Americans followed close after the French, and the tide of immigration became Anglo-Saxon. France was openly supporting the American colonies in their rebellion against England, and in 1779 Spain declared war against Great Britain, so that the sympathies of the Creoles were led, by every tie, to the rebels. Galvez, then Governor of Louisiana, and also son of the Viceroy of Mexico, a young man, brave, talented and sagacious, who had adopted a most liberal policy in his administration, discovered that the British were planning the surprise of New Orleans. Making hasty but efficient preparations, with a little army of 1,430 men, and with a miniature gun fleet of but ten guns, he marched, on the twenty-second of August, 1779, against the British forts on the Mississippi. On the seventh of September, Fort Bute, on Bayou Manchac, yielded to the first assault of the Creole Militia. The Fort of Baton Rouge was garrisoned by five hundred men with thirteen heavy guns. On the twenty-first of September, after an engagement of ten hours, Galvez reached the fort. Its capitulation included the surrender of Fort Panmure, a place which, by its position, would have been very difficult of assault. In the Mississippi and Manchac, four English schooners, a brig and two cutters were captured. On the fourteenth of the following March, Galvez, with an army of two thousand men, having set sail down the Mississippi, captured Fort Charlotte, on the Mobile River. On the eighth of May, 1781, Pensacola, with a garrison of eight hundred men, and the whole of West Florida, surrendered to Galvez. One of the rewards bestowed upon her Governor for his valorous achievements was the Captain-generalship of Louisiana and West Florida. He never returned to New Orleans, however, and four years later succeeded his father as Viceroy of Mexico. Thus, while Andrew Jackson was yet a child, New Orleans was defended from British conquest by this gallant Spanish soldier.

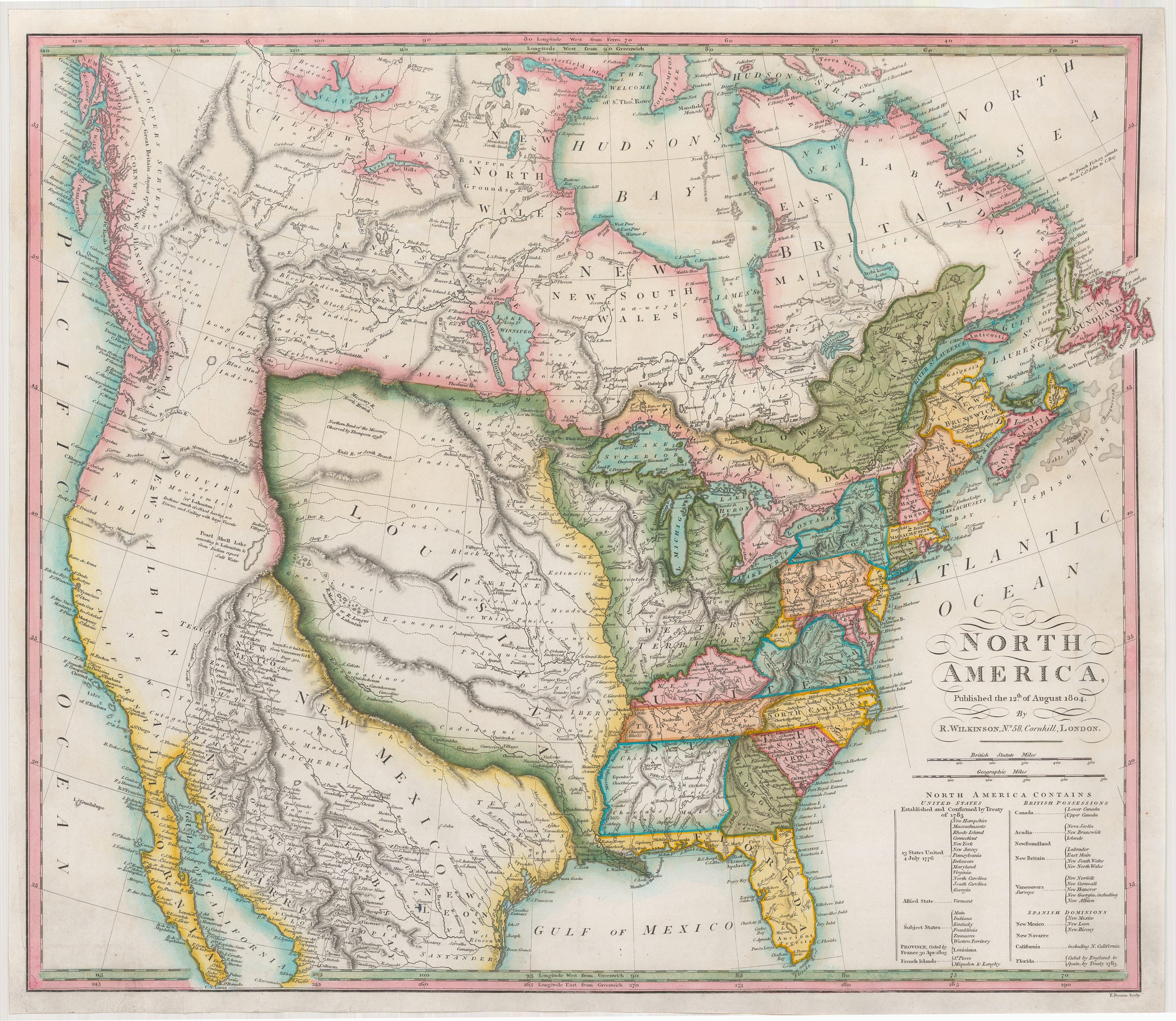

In 1803 Louisiana was transferred to France by Spain, and great was the rejoicing of the Creole colonists, who, during the forty years of their Spanish domination, had never forgotten their French origin. But their joy was quickly turned to bitterness by the news which speedily followed, that Louisiana had been sold, by Napoleon I, to the United States. The younger generation, and those who had a clear apprehension of all in the way of prosperity which this change might mean to them, were quickly reconciled, and set about the business of life with renewed interest. But to the French Creoles, as a class, who, during their long alienation had still at heart been thoroughly French, to become a part of a republic, and that republic English in its origin, was intensely distasteful. This was the deluge indeed, which Providence had not kindly stayed until after their time. They withdrew into a little community of their own, and refused companionship with such as sacrificed their caste by accepting the situation, and adapting themselves to it. But in spite of these disaffected persons, the prosperity of the city dated from that time. Its population increased, and its commerce made its first small beginnings.

12 August 1804. London: R. Wilkinson.

New Orleans was incorporated as a city in 1804, having then a population of about 8,000 inhabitants. In 1812 the first steamboat was put upon the Mississippi, though it was not until several years later that, after a period of experiment and disaster, success was attained with them. Yet without steamboats the development of the great Mississippi Valley, and the creation of the extended cities upon its banks, would have been well-nigh impossible. Its winding course, its swift current, its shifting channel, and the snags which line its bottom, make navigation by other craft than steamboats well-nigh impossible. Canoes, batteaux and flat-boats might make the voyage down the river with tolerable speed and safety, but to return against the current was a difficult thing to do; and a trip from St. Louis or Louisville to New Orleans and return required months. Where, then, would have been the mighty commerce of the West, but for the timely invention of the steam engine, and its application to water craft?

On January eighth, 1815, New Orleans was successfully defended against the British by General Jackson, who threw up a strong line of defences around the city, protected by batteries, and who, with a force of scarcely six thousand men, defeated fifteen thousand British, under Sir Edward Packenham, the enemy sustaining a loss of seven hundred killed, fourteen hundred wounded, and five hundred taken prisoners, while the American loss was but seven men killed and six wounded. The old battle field is still retained as a historic spot. It is four and one-half miles south of Canal street, washed by the waters of the Mississippi, and extends backward about a mile, to the cedar swamps. A marble monument, seventy feet in height, and yet unfinished, commemorative of the victory, overlooks the ground. In the southwest corner of the field is a national cemetery.

The old city bears the impress of the two nations to which it at different times belonged. Many of the streets still retain the old French and Spanish names, as, for instance, Tchapitoulas, Baronne, Perdido, Toulouse, Bourbon and Burgundy streets. There are still, here and there, the old houses, sandwiched in between those of a later generation — quaint, dilapidated, and picturesque. Sometimes they are rickety, wooden structures, with overhanging porticoes, and with windows and doors all out of perpendicular, and ready to crumble to ruin with age. Others are massive stone or brick structures, with great arched doorways, and paved floors, worn by the feet of many generations, dilapidated and heavy, and possessing no beauty save that which is lent them by time.

The city is made up of strange compounds, which even yet, after the lapse of more than three-quarters of a century since it became an American city, do not perfectly assimilate. Spanish, French, Italians, Mexicans and Indians, Creoles, West Indians, Negroes and Mulattoes of every shade, from shiny black to a faint creamy hue, Southerners who have forgotten their foreign blood, Northerners, Westerners, Germans, Irish and Scandinavians, all come together here, and jostle one another in the busy pursuits of life. The levee at New Orleans represents all spoken languages; and the popular levee clerk must have a knowledge of multitudinous tongues, which would have secured him a high and authoritative position at Babel. The Romish devotee, the mild-faced “sister,” in her ugly black habiliments and picturesque head-gear, the disciple of Confucius, the descendant of the New England Puritan, the dusky savage, who still looks to the Great Spirit as the giver of all life and light, the modern skeptic, and the black devotee of Voodoo, all meet and pass and repass each other. All nationalities, all religions, all civilizations, meet and mingle to make up this city, which, upholding the cross to indicate its religion, still, in its municipal character, accepts the Mohammedan symbol of the crescent. Added to the throng which comes and goes upon the levee, merchants, clerks, hotel runners, hackmen, stevedores, and river men of all grades, keep up a general motion and excitement, while piled upon the platforms which serve as a connecting link between the water-craft and the shore, are packages of merchandise in every conceivable shape, cotton bales seeming to be most numerous.

Along the river front are congregated hundreds of steamers, and thousands of nondescript boats, among them numerous barges and flat-boats, thickly interspersed with ships of the largest size, from whose masts float the colors of every nation in the civilized world. New Orleans is emphatically a commercial town, depending in only a small degree, for her success, upon manufactures.

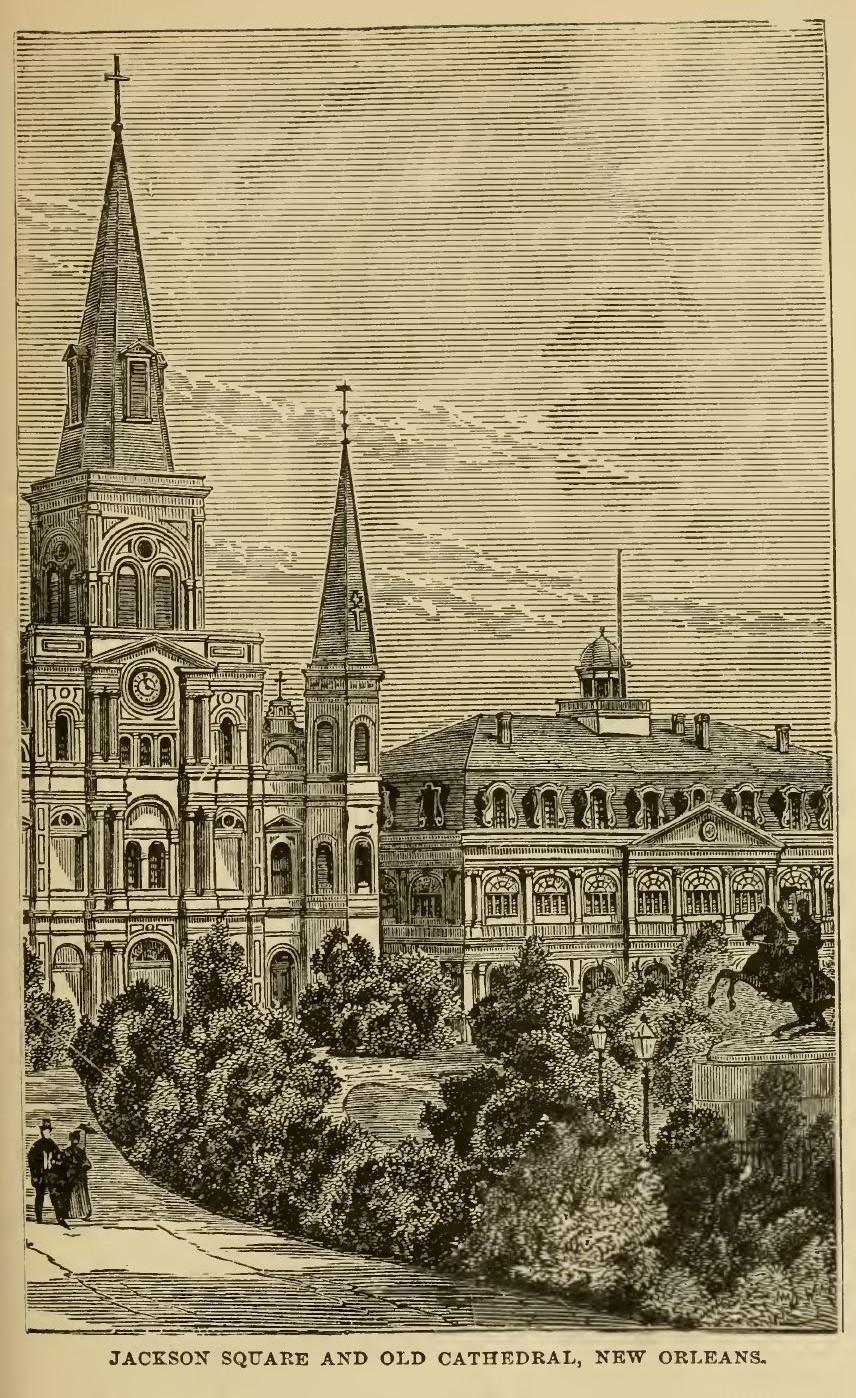

New Orleans is not a handsome city, architecturally speaking, though it has a number of fine buildings. Its situation is such that it could never become imposing, under the most favorable circumstances. The Custom House, a magnificent structure, built of Quincy granite, is, next to the Capitol at Washington, the largest building in the United States. It occupies an entire square, its main front being on Canal street, the broadest and handsomest thoroughfare in the city. The Post Office occupies its basement, and is one of the most commodious in the country. The State House is located on St. Louis street, between Royal and Chartres streets, and was known, until 1874, as the St. Louis Hotel. The old dining hall is one of the most beautiful rooms in the country, and the great inner circle of the dome is richly frescoed, with allegorical scenes and busts of eminent Americans. The United States Branch Mint, at the corner of Esplanade and Decatur streets, is an imposing building, in the Ionian style. The City Hall, at the intersection of St. Charles and Lafayette streets, is the most artistic of the public buildings of the city. It is of white marble, in the Ionic style, with a wide and high flight of granite steps, leading to a beautiful portico. The old Roman Catholic Cathedral of St. Louis is the most interesting church edifice in New Orleans. It stands in Chartres street, on the east side of Jackson Square. The foundations were laid in 1793, and the building completed in 1794, by Don Andre Almonaster, perpetual regidor of the province. It was altered and enlarged in 1850. The paintings in the roof of the building are by Canova and Rossi. The old Ursuline Convent, in Conde street, a quaint and venerable building, erected in 1787, during the reign of Carlos III, by Don Andre Almonaster, is one of the most interesting relics of the early Church history of New Orleans. It is now occupied as a residence by the Bishop.

The Charity Hospital, on Common street, was founded in 1784, has stood on its present site since 1832, and is one of the most famous institutions of the kind in the country. Roman Catholic churches, schools, hospitals and asylums abound, some of them dating back for nearly or quite a century.

The St. Charles Hotel is one of the institutions of New Orleans, and one of the largest and finest hotels in the United States. It occupies half a square, and is bounded by St. Charles, Gravior and Common streets. The city has a French opera house, an academy of music, and several theatres and halls. Like those of St. Louis, its inhabitants are passionately fond of gayety, and places of amusement are well patronized. Sunday, as in all Catholic cities, is devoted to recreation, and the inhabitants, in their holiday garments, give themselves up to enjoyment. Theatres, concert rooms and beer gardens are filled with pleasure-seekers.

Canal street, the main business thoroughfare and promenade of New Orleans, is nearly two hundred feet wide, and has a grass plot twenty-five feet wide, in the centre, bordered on each side by trees. Claiborne, Rampart, St. Charles and Esplanade streets are similarly embellished. They all contain many fine stores and handsome residences. Royal, Rampart and Esplanade streets are the principal promenades of the French quarter. The favorite drives are out the Shell Road to Lake Pontchartrain, and out a similar road to Carrollton. The lake is about five miles north of the city, forty miles long and twenty-four wide, and is famous for its fish and game. Cypress swamps, the trees covered with the long, gray Spanish moss peculiar to the latitude, lie between the lake and the city, and render the drive in that direction an interesting one.

Carrollton, in the north suburbs, has many fine public gardens and private residences. On the opposite shore of the river is Algiers, where there are extensive dry docks and ship-yards. A little further up the river, on the same side, is Gretna, where, during Spanish rule, lay moored two large floating English warehouses, fitted up with counters and shelves, and stocked with assorted merchandise.

New Orleans has a few small, tastefully laid out squares, among which are Jackson, Lafayette, Douglass, Annunciation and Tivoli Circle. The City Park, near the northeast boundary, contains one hundred and fifty acres, which are tastefully laid out, but which is little frequented. Jackson Square has a historic interest, it having been the old Place d’Armes of colonial times. It was here that Ulloa landed in that ill-omened thunder storm, and here that public meetings were held and the colony’s small armies gathered together. The inclosure, though small, is adorned with beautiful trees and shrubbery, and shell-strewn paths, and in the centre stands Mills’ equestrian statue of General Jackson.

The city is not without other objects of historic interest. During the Indian wars barracks arose on either side of the Place d’Armes, and in 1758 other barracks were added, a part of whose ruin still stands, in the neighborhood of Barracks street. Then there is the battle field, already referred to, and many buildings belonging to a past century, some of which have distinctive historic associations. Near Jackson Square is the site of the oldest Capuchin Monastery in the United States. Sailing down the Mississippi, the voyager will reach a portion of the stream which flows almost directly south. Here is a point in the river which bears the name, to this day, of the English Turn. Up the mouth of the Mississippi sailed one day, in the seventeenth century, a proud English vessel, bent on exploration and acquisition of territory to England. Threading for a hundred miles the comparatively direct course of the stream, it had then made two abrupt right-angled turns, when, coming around a third point, in advance of it, it saw a French ship, armed and equipped, and bearing down stream under full sail. The English ship was given to understand that the Mississippi was “no thoroughfare”for boats of its nationality, and commanded to turn and retrace its course, which it reluctantly, but no less surely did. Hence the name “English Turn.”

The Cemeteries of New Orleans are most peculiar in their arrangement and modes of interment. The ground is filled with water up to within two or three feet of the surface, and the tombs are all above ground. A great majority of them are also placed one above another. Each “oven,”as it is called, is just large enough to admit a coffin, and is hermetically sealed when the funeral rites are over. A marble tablet is usually placed upon the brick opening. Some of the structures are, however, costly and beautiful, being made of marble, granite or iron. There are thirty-three cemeteries in and near the city, and of these the Cypress Grove and Greenwood are best worth visiting.

The most picturesque and characteristic feature of New Orleans is the French Market, on the Levee, near Jackson Square. The gathering begins at break of day on week-days and a little later on Sunday morning, and comprises people of every nationality represented in the city. French is the prevailing language, but it will be heard in every variety, from the pure Parisian to the childish jargon of the negroes.

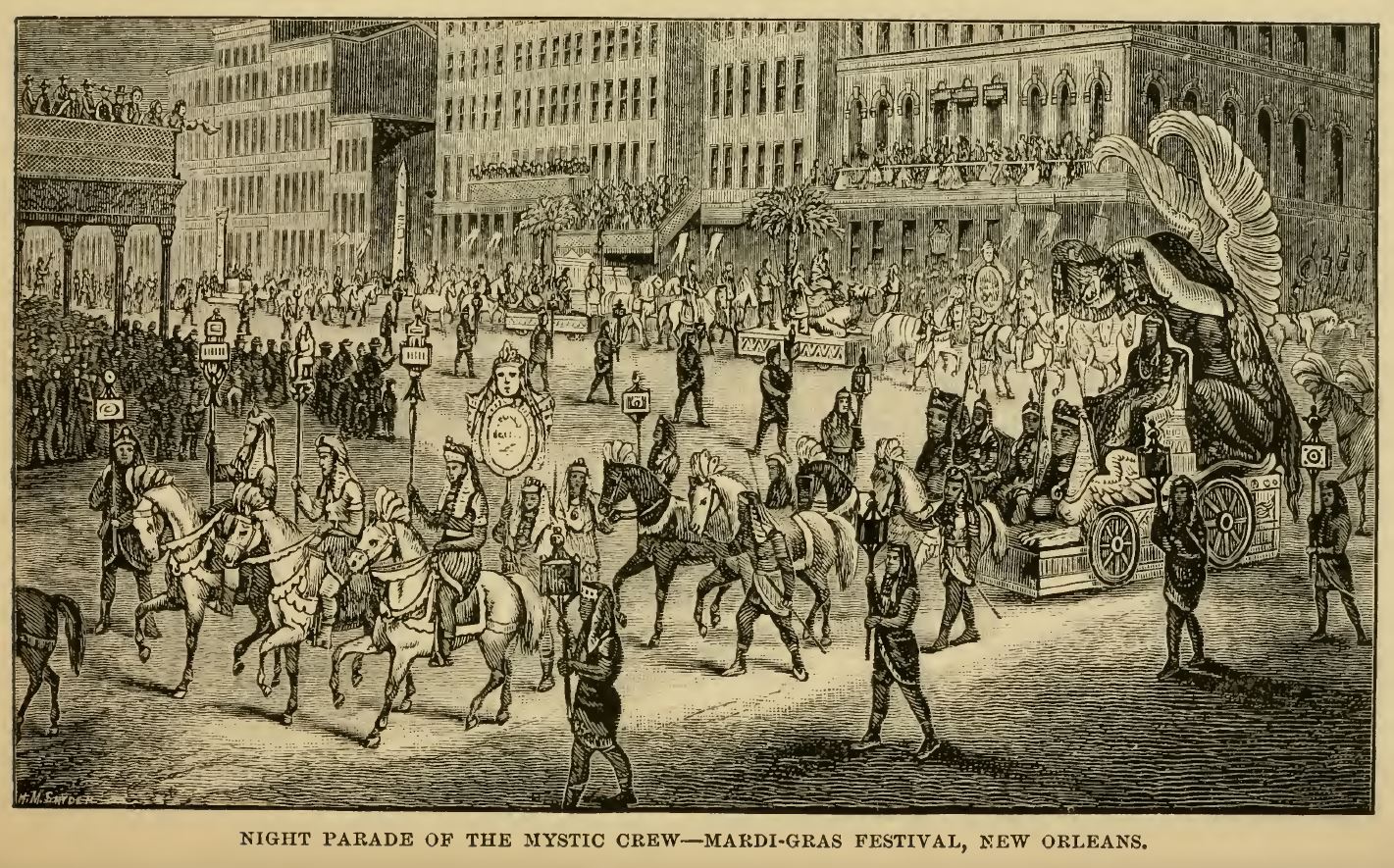

MARDI-GRAS FESTIVAL, NEW ORLEANS.

Mardi-Gras, or Shrove Tuesday, is observed in New Orleans by peculiar rites and ceremonies. Rex, King of the Carnival, takes possession of the city, and passes through the streets, accompanied by a large retinue, his staff and courtiers robed in Oriental splendor. The city gives itself up to mirth and gayety, with an abandon only paralleled by that witnessed in Italy on the same occasion; and the day is concluded by receptions, tableaux and balls.

New Orleans boasts a semi-tropical climate, being situated in latitude 29° 58′ north. The summers are oppressively hot, but the winters are mild and pleasant, with just sufficient frost to kill any germs of disease engendered by her unhealthful situation. Semi-tropical fruits, such as the orange, banana, fig and pine-apple, grow readily in her gardens, where are also cultivated many of the productions of the temperate zone. The neighboring country is clothed with a rich and luxuriant semi-tropical vegetation, and forests of perennial green, in which the cypress and live-oak predominate.

New Orleans had a population, in 1820, of 27,000. In 1850 it had increased to 116,375, and in 1860 to 168,675. In common with other cities of the South, New Orleans suffered in her business interests severely during the war of the Rebellion. Louisiana having seceded from the Union in 1861, New Orleans was closely blockaded by the Federal fleet, and on April twenty-fourth, 1862, the defences near the mouth of the river were forced by Commodore Farragut, in command of an expedition of gunboats. On the surrender of the city General B. F. Butler was appointed its military Governor, and held possession of it until the close of the war. Its commerce was entirely destroyed during that period, its business interests crushed, and many of its leading men impoverished, and, in addition, the State was disturbed by intestine troubles, which kept affairs in an unsettled condition. New Orleans did not rally as quickly as St. Louis from the effects of the war. Nevertheless, in 1870 its population had increased to 191,418, and in 1874 the value of its exports, including rice, flour, pork, tobacco, sugar, etc., but excepting cotton, were estimated at $93,715,710. Its imports the same year were valued at more than $14,000,000. It is the chief cotton mart of the world, and its wharves are lined with ships which bear this commodity to every quarter of the globe. In the amount and value of its exports, it ranks second only to New York, though its imports are not in the same proportion, which always speaks well for the business prosperity of a city. The census of 1880 gave it a population of 216,140, showing that its progress still continues. No longer cursed by the presence of the “peculiar institution," its former slave marts turned into commercial depots or abolished altogether, and its population numbering to a greater degree every year the industrious class, New Orleans will do more in the future than maintain her present prosperity; she will build up new industries, and originate new schemes of advancement; so that she is certain to continue her present supremacy over her sister cities in the South.

Notes

- “Filles de Casette.” Translated as the Casquette Girls. Although the word ‘casquette’ sounds like ‘casket,’ it means a small chest, which the girls packed their possessions in.

Text prepared by:

- Abby Buzulak

- Bruce R. Magee

- Wariebi Suobo

- Maiyah Tellis

Source

Glazier, Willard. “Peculiarities of New Orleans.” Peculiarities of American Cities. Philadelphia: Hubbard Brothers, 1886. 264-280. Archive.org. Internet Archive, 19 May 2009. Web. 10 May 2018. <https:// archive.org/ details/ peculiarities ofa01glaz>.