Alice Dunbar-Nelson.

“The Problem of Personal Service.”

Most of us are familiar with the sight of the middle-class white woman going from door to door in the frankly colored neighborhood, ringing the bells and asking with honeyed accents of condescension, “I wonder if you could tell me where I can get a good cook (or laundress or housemaid)”; and the blunt reply of the stout colored dame, as she holds the door against Nordic intrusion, “’Deed, I couldn’t tell you ma’am, I need a girl myself.”

That is one phase of the problem of personal service — many of us dislike the term “domestic” service — it has collected such a variety of unpleasant connotations. But the situation must have reached an acute condition if we are to judge by the findings of the group of rich New York women, headed by Mrs. Boardman, which has decided to place servants in the professional class. Service is to be on a par with other operations in the business world, and the supposed stigma which is attached to domestic employment is to be removed. The maid and cook and laundress will be graduates of schools for their training. They will have regular hours. They will be addressed by the title “Miss” or “Mrs.” and all the rest of it. But as the Philadelphia Record whimsically objects, what about the price paid to these super-servants?

Our race knows that this solution will not touch us. When super-servants are to be employed, with all the frills and appurtenances, including the gracious form of address, we well know the Caucasian female of the species will not have to pay a dark-skinned girl the price, nor be willing to accord her the position of business employee rather than personal maid. And after all, there will be comparatively few even of the wealthiest class who will be able or willing to pay the price for this superior class of domestics.

So that leaves the problem exactly where it was at the beginning.

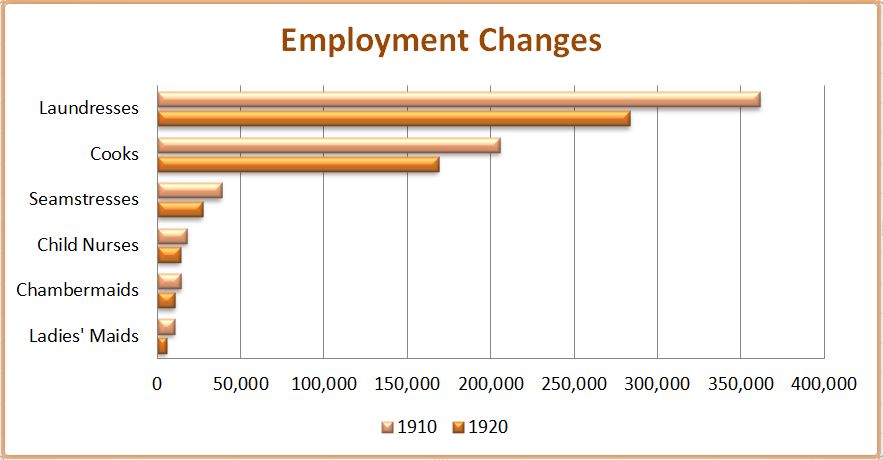

We have noticed before that the number of ladies maids has dropped from 10,239 in 1910 to 5,488 in 1920. Of chambermaids from 14,071 in 1910 to 10,443 in 1920. Of child nurses from 17,874 in 1910 to 13,888 in 1920. Of dressmakers and seamstresses from 38,277 in 1910 to 26,961 in 1920. Of cooks from 205,584 in 1910, to 168,443 in 1920. Of laundresses, not in laundries, from 361,551 in 1910 to 283,557 in 1920. We have noted, too, that women are leaving the ranks of personal service for the easier (so far as hours go) and better paid work in mills, industries, factories.

But there are phases of personal service that are attractive. Board and lodging being often included, the wages are “clear,” and the work is often so planned that there is not the strain, the constant being on tiptoe that is necessary in the industrial and professional world. Often, too, contacts, that are afterwards remunerative, are made. If there were an adequate protection afforded the girl or woman who goes into personal service, either as a career, a stop-gap, a summer avocation, or a means to an end, there is hardly any phase of the work-a-day world that would offer better opportunities for the girl forced to leave school before she has gained her high school diploma, or for one who has done so.

And that adequate protection of the woman in personalservice can come only from intelligent organization into a union that will safeguard her interests, protect her morals, assure her of a home when temporarily out of employment, and give her accurate card catalogue information of prospective employers.

This is an idea neither new nor original. During the war, Miss Eartha M. White, of Jacksonville, Florida, had under her direction a most excellent union of women in war work, whether elevator runners, drivers of trucks, special domestic servants or what not. It had possibilities, that union did. It may still exist, but if so, its activities are of the soundless variety. Perhaps the closing of the war, releasing the women from their unusual duties caused a cessation of interest.

Four or five years ago, Miss Nannie Burroughs, of Washington, D.C., conceived the idea of a Domestic Servants Organization, with rules, regulations and projects similar to the unions among men laborers or skilled workmen. It was a magnificent idea, and with her customary smashing skill, Miss Burroughs put it across in quite a bit of the territory of the United States. A building was bought and operated for the girls in the heart of northwest Washington. It is a sort of Social Center, with classes, lodging rooms, recreation rooms, dining rooms, where excellent meals can be obtained at small cost, and all the rest of it.

But the appeal was never national. For one thing, to put such an idea across, trained organizers and speakers must be on the go all the time, reaching the women in small towns, as well as in large ones, and hammering, hammering away at the idea. And that takes money. And Miss Burroughs had no money. And not much time to do the work herself, since the life of her own school, the National Training School, depends upon her own efforts.

And that still leaves the problem in the air.

Only those who have had dealings with the middle-class employer of colored girls know that those girls sometimes have to endure to get a fair living wage. We know by heart the tales of the miserable sleeping quarters, the long and uncertain hours, the lonely evenings, which ofttimes end in surreptitious visits to any place where company and pleasure may be had. Small wonder then, that girls drift into factories — and they are pretty poor factories in the Middle Atlantic and Southern states which employ colored girls. Small wonder that domestic service is shunned. There is too much uncertainty about its operations.

Girls under the charge of institutions who are paroled to service, fare much better. The parole officer, or visiting officer, sees to it that the girl’s room is adequately furnished, is warm and attractive. She insists upon recreation and hours off. She places a valuation upon the girl’s services, and sees that she is so recompensed. And the paroled girl is correspondingly respected because there is law behind her. She is apt to be free from the unwelcome attentions of the men of the house — for no man relishes being hauled into court on the charge of “contributing to the delinquency of a minor” or “interfering with the safety of a ward of the state.”

Text prepared by:

- Bruce R. Magee

Source

Dunbar-Nelson, Alice. “The Problem of Personal Service.” Print.