Baron Marc de Villiers.

A History of the Foundation of New Orleans (1717-1722).

Trans. Warrington Dawson.

by Jacques-André-Joseph Aved.

FOREWORD

ATITUDE

must be allowed in the use of the term foundation, when speaking of New Orleans. According to the interpretation given, the date may be made to vary by six years, or even much more.

ATITUDE

must be allowed in the use of the term foundation, when speaking of New Orleans. According to the interpretation given, the date may be made to vary by six years, or even much more.

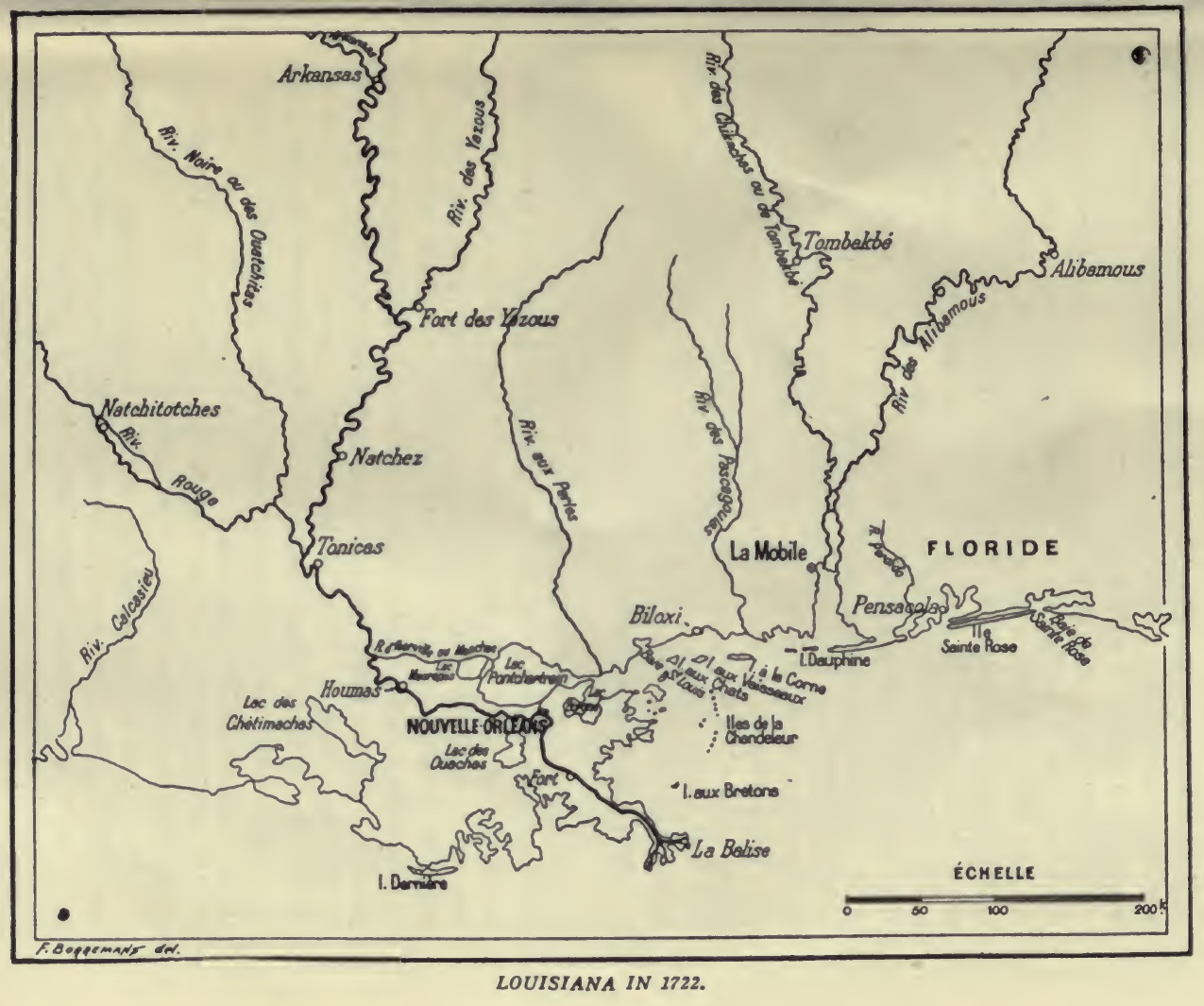

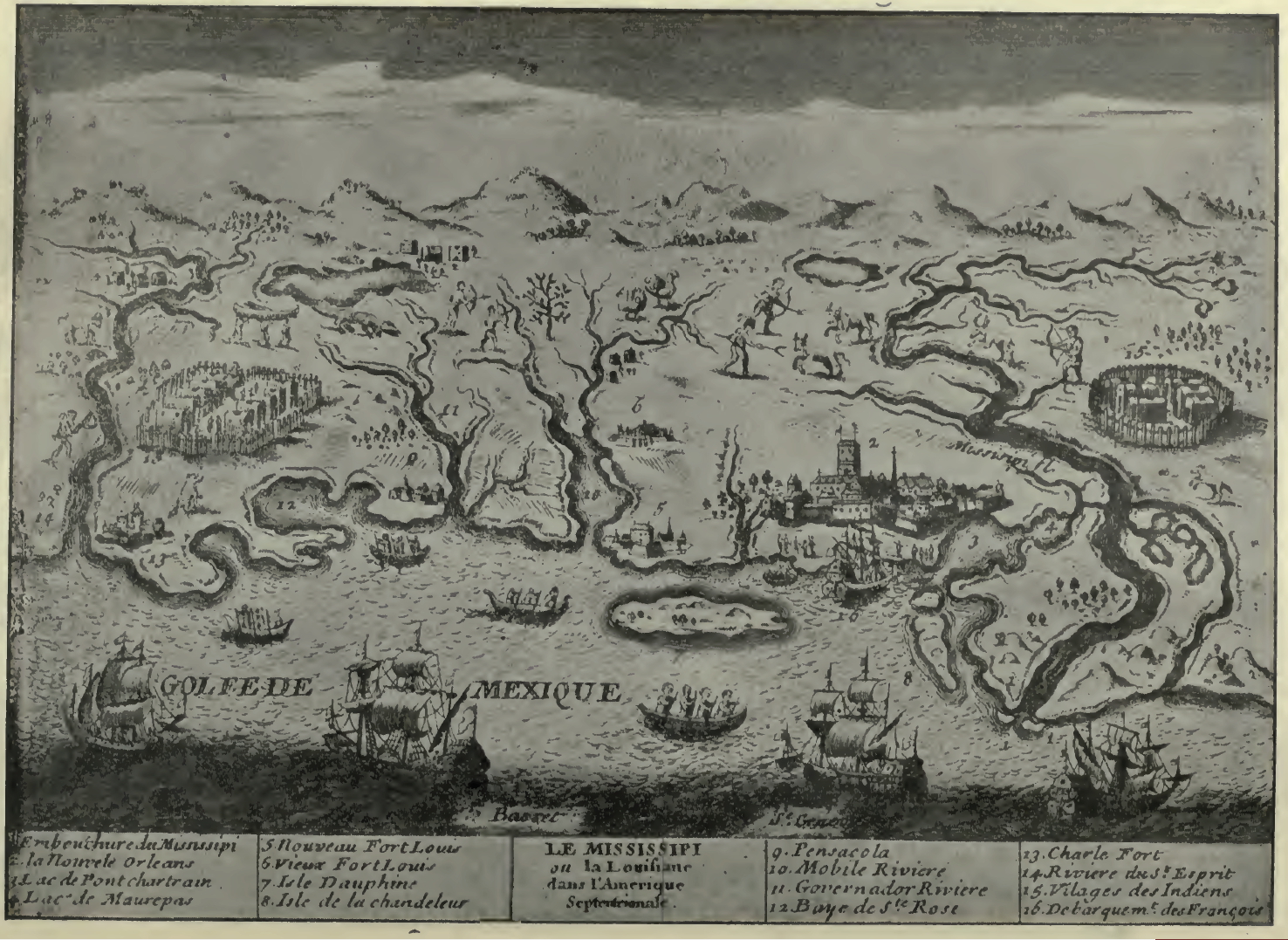

Since time immemorial, the present site of Louisiana’s capital had been a camping-ground for Indians going from the Mississippi to the mouth of the Mobile River. As soon as the French had settled on Massacre Island, that site became the customary landing-place for travellers on the Father of Waters. Wherefore the history of New Orleans might be said to date from the winter of 1715-1716, when Crozat demanded that a post be founded where the city now stands; or even from 1702, in which year M. de Remonville proposed the creation of an establishment “at the Mississippi Portage.”

And yet, a lapse of fifteen years, which might be almost qualified as proto-historic, put a check upon the Colony’s development. Then Bienville revived Remonville’s project. The Marine Board at last harkened to reason, and, in concert with the Company of the West, appointed, on the 1st of October, 1717, a cashier in New Orleans.

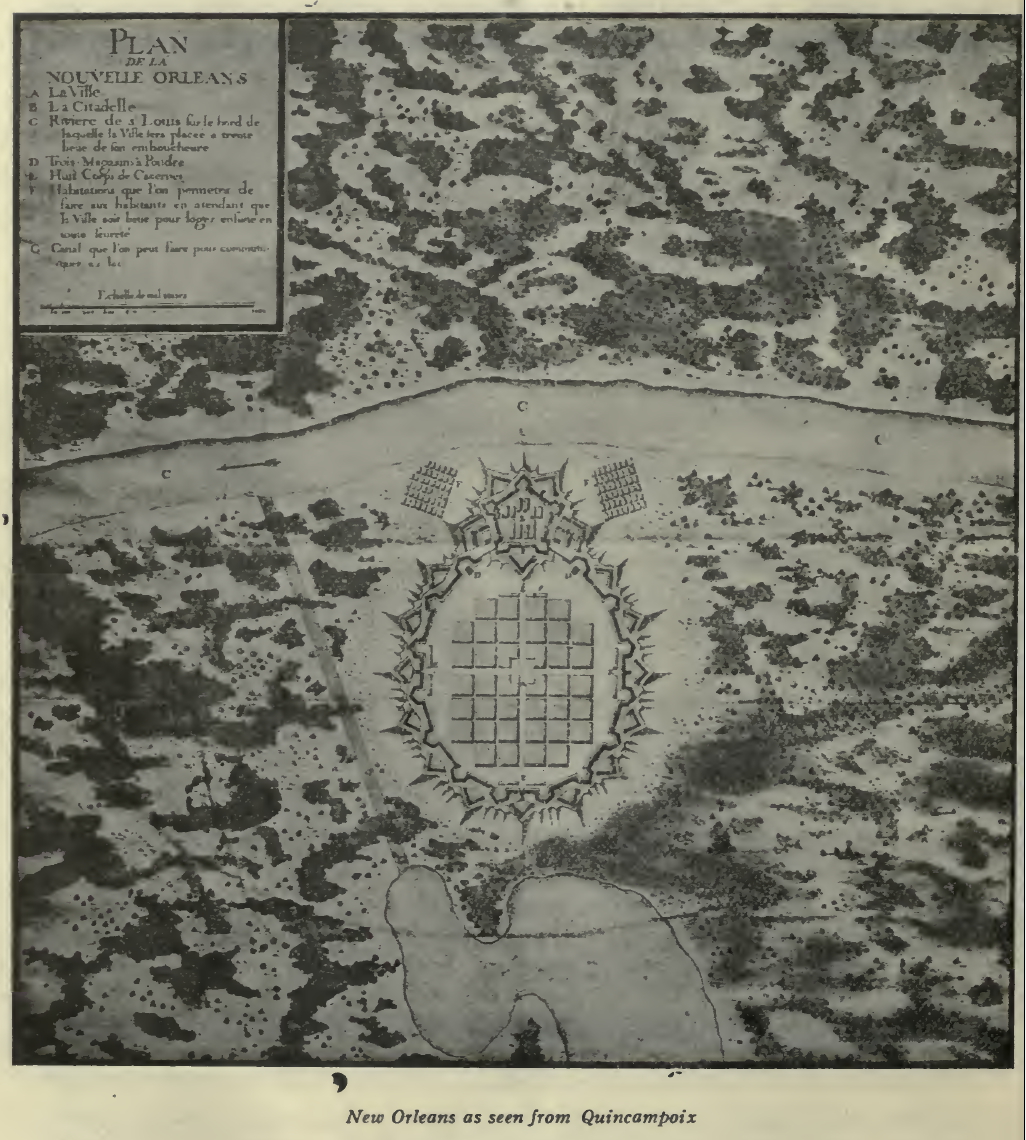

Land was not broken, however, until the end of March, 1718. Even then, work progressed slowly, owing to the hostility of settlers along the coast. A year later, the new post consisted but of a few sheds built of boughs surrounding a “hut thatched with palm-leaves.” The great Mississippi flood followed in 1719, and then came the war with Spain. New Orleans was all but abandoned. At Paris, Rue Quincampoix, marvellous drawings were displayed. But in January, 1720, Bienville could count, within the circumference of a league, “only four houses under way.”

News of the flood had been considerably exaggerated by partisans of Mobile or of Biloxi. The Directors of the Company of the Indies stopped work on the new counter. There was even talk of transferring it to the Manchac Plain, about a dozen leagues farther north.

Thanks to Bienville’s tenacity, New Orleans was never completely abandoned, and so managed to exist until the decision of the 23rd of December, 1721, reached Louisiana, raising the town to the rank of capital.

So the date for the foundation of New Orleans may be fixed at pleasure anywhere between the spring of 1717 and the month of June, 1722, when Le Blond de La Tour, the Engineer-in-Chief, compelled to go and visit the site of the capital, had no choice but to ratify purely and simply the plan drawn up a year before by Adrien de Pauger.

In 1720, Le Maire, one of the Colony’s best geographers, still obstinately refused to mark the place on his map. Franquet de Chaville, the engineer, one of the founders of the town, declares, categorically in favor of the year 1722. According to Pénicaut, Father Charlevoix gives 1717. Even by eliminating 1722 and 1721 and 1719, when the great flood occurred-the years 1717, 1718, and 1720 remain. Stoddart rejects historical subtleties and chooses 1720. (Sketches Historical and Descriptive of Louisiana, 1812.) More circumspect, the Chevalier de Champigny asserts in 1776, in his Etat present de la Louisiane: “New Orleans was founded by Bienville in 1718, 1719, and 1720.”

The surest date would appear to be 1718. Nevertheless, 1717, recalling the official foundation of New Orleans in Paris, might be adopted, for with towns as with men, a christening is a species of consecration. Furthermore, in French territory, where administrative formalities thrive to excess, can it be alleged that a town which boasts a cashier and a mayor does not exist?

In its prolonged uncertainty, the fate of New Orleans suggests that of a seed cast hap-hazard on uncultivated soil. At the end of a year it might begin to sprout, but, unable to thrust its roots firmly down, might remain latently alive, always exposed to chance gusts of wind seeking to blow it away. Luckily, the germ of the future capital took to the water as naturally as did its soil. The inundation of 1719, after very nearly drowning New Orleans, ended by settling it firmly upon the fine crescent of the Mississippi.

HISTORY OF THE FOUNDATION

OF NEW ORLEANS

(1717-1722)

CHAPTER I.

The Mississippi Portage.

XPLORING

the region in 1682, Robert Cavelier de La Salle, Henri de Tonty, the Sieur de Bois-rondet, La Metairie, the notary, Father Zenobe, and their eighteen companions, beheld the site on which Louisiana’s capital was destined to prosper.

XPLORING

the region in 1682, Robert Cavelier de La Salle, Henri de Tonty, the Sieur de Bois-rondet, La Metairie, the notary, Father Zenobe, and their eighteen companions, beheld the site on which Louisiana’s capital was destined to prosper.

On the 31st of March, they “passed the Houmas’ village without knowing it, because of the fog and because it was rather far away.” After a slight skirmish against the Quinipissas, they discovered, at the end of three days, the Tangibaho village, recently destroyed by the Houmas, and they “hutted on the left bank, two leagues below.”

It is difficult to locate with any degree of precision the village mentioned by La Salle, or by Tonty a few years later. Complications arise from the fact that, soon after the Europeans had passed, several Indian tribes of the region, notably the Tinsas, the Bayou-goulas, and the Colapissas, emigrated northward, or else disappeared more or less completely, like the Mahouelas, who seemed to have denizened the Tangibaho village. Furthermore, Louisiana Indians observed the primitive custom of abandoning their huts when the chief died.

Nevertheless, an attentive comparison of the letters and narratives of Cavelier de La Salle, of La Metairie, of Nicolas de La Salle, of Tonty, of Iberville, and of Le Sueur, leads to the conclusion that the Tangibaho village, situated in the Quinipissas’ territory, and whose portage passed through its centre, must have lain very near the present site of New Orleans.

Three years had passed when Tonty learned at Fort St. Louis in Illinois that “M. de LaSalle a descent upon the Florida coast, that he was fighting the savages and lacked provisions.” The valiant pioneer went down the Mississippi, and on the 8th of April, 1686, reached the Quinipissa village. Being unable, however, to gather any information about the expedition of his former chief, he was soon compelled to turn back towards Illinois.

Shortly after, the Quinipissas (Tonty writes indifferently Quinipissas or Quinépicas dispersed, and a certain number from among them fused with the Mougoulachas, a tribe related to the Baya-goulas. Launay, one of Tonty’s companions, makes a formal statement to this effect. So we may explain how Bienville found the Mougoulachas in possession of the letter for La Salle which Tonty had left with the Quinipissas. And yet, the last named tribe had not totally disappeared, since Tonty wrote, on the 28th of February, 1700: “The Qunipissas, the Bayagoulas, and the Mougoulachas number about one hundred and eighty men.” (Sauvoile wrote Maugaulachos.)

The first explorers of Louisiana, knowing little about the usages and being imperfectly acquainted with the tongue of local Indians, mistook for distinct tribal denominations all the proper names they heard. In 1701, Sauvolle still reckoned thirty-six in a territory occupied by only five or six separate tribes. Le Maire was among the earliest to avoid this error. He wrote in 1718: “The names with which old maps bristle are not so much those of different nations, as distinctions of those who, within one nation, to secure lands for themselves have parted from the main village and have chosen titles to serve as identification. Between the Tonicas and the Houmas were the Tchetimatchas, who formerly extended as far as the sea. This nation was driven away after having murdered a missionary (Father St. Come) and they are now wanderers. Another nation, formerly connected with this one, separated from it to avoid being implicated in the war waged against the Tchetimatchas, and four years ago settled down with the Houmas.” (Archives Nationales, Colonies, C13c,2,f° 164.) Le Maire refers to the Indians established near English Turn, numbering sixty men, as Cuzaouachas.

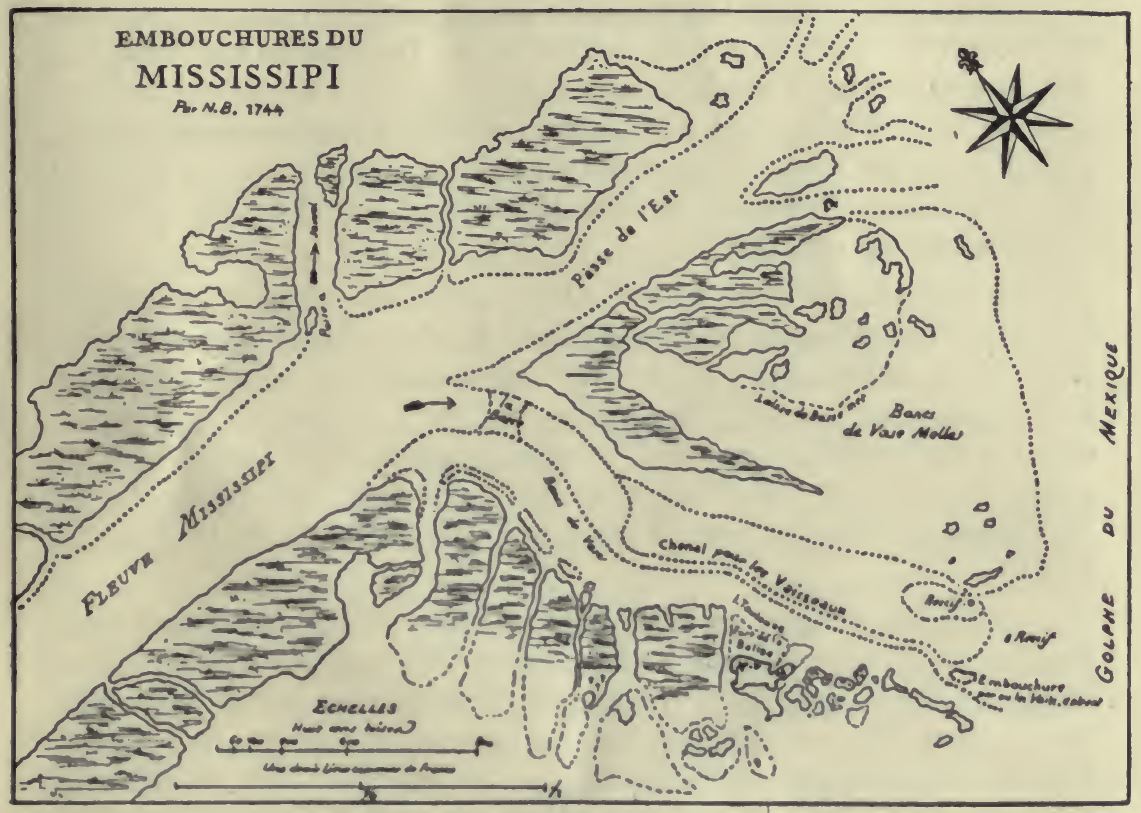

Luckier than the ill-fated Cavelier de La Salle, who had been miserably murdered before reaching the St. Louis River, Le Moyne d’Iberville succeeded after many difficulties in approaching by sea and so discovered the mouths of the Mississippi, in 1699.

Owing to this circumstance, the name of Malbanchia would seemingly have been more appropriate for the great river. The name Mississippi, by which the Illinois knew it, was totally unknown to tribes living south of Arkansas. If the river had been originally discovered from the mouth, it would probably have been Malbanchia. According to Pellerin, the savages near Natchez called the Mississippi, in 1720, the Barbanca or else the Missouri.

“Mississippi, or River Everywhere,” says an anonymous memoir in the National Archives, “comes from the Ontoubas word Missi or the Illinois Minoui, everywhere, and Sipy, river, because this river, when it overflows, extends its channels over all the lands, which are flooded and become rivers everywhere. It is also called Michisipy, Great River; and the Illinois call it Metchagamoui, or more commonly Messesipy or Missi-Sipy, All-River, because all the rivers, that is to say very many, empty into it, from its source to its mouth.” (Arch. Nat., Colonies, C13c,4,f° 164.)

On the 9th of March, 1699, Iberville observed the site where New Orleans was eventually to rise.

“The savage I had with me,” he writes on that date, “showed me the place which the savages have as their portage, from the end of the bay where our ships are anchored, to reach this river. They dragged their canoes over a fairly good path; we found there several pieces of baggage belonging to people going one way or the other. He pointed out to me that the total distance was very short.”

Next year, Iberville profited by information he had received, and passed through Lake Pontchartrain to reach the Mississippi:

“18th January — I have been to the portage,” he writes. “I found it to be about half a league long; half the way full of woods and of water reaching well up on the leg, and the other half good enough, a country of cane-brakes and woods. I visited one spot, a league beneath the portage, where the Bayagoulas (this word has veen crossed out and replaced by Quinipissas) formerly had a village, which I found to be full of canes, and where the soil is but slightly flooded. I have had a small desert made, where I planted sugar-canes brought by me from Martinique; I don’t know if they will take, for the exhalations are strong.” (Arch. Hydrog. 115x,N°5,f° 16.)

A month later, Le Sueur, starting out on his exploration of the upper Mississippi, and Tonty, who had come to put himself at the disposal of his compatriots, met here. At this period, the portage-way could not have been broken, since Le Sueur’s porters were several times lost in the cypress swamps. Two of the men even had their feet frozen from spending a night tinder such conditions; in consequence of which accident the way was occasionally referred to, and for a considerable while, as “The portage of the Lost.” A map dated 1735 gives it this name.

Pénicaut, one of Le Sueur’s companions, camped on the site of New Orleans and slept under enormous cypresses which served at night as perches for innumerable “Indian fowls weighing nearly thirty pounds, and all ready for the spit.” Gunshots did not frighten them.

New Orleans is situated just below the thirtieth degree of North latitude. Iberville and Le Sueur both took the bearings of the portage; their calculation, verified by Delisle, indicated 29°58′ and 30°3′ In 1729, Brown, the astronomer, profiting by an eclipse, found 29°57′. This portage, before becoming definitely that of Bayou St. John, or of New Orleans, was endowed with the most varied names. It is called indifferently the Portage of the Lost; of Billochy (original spelling of Biloxi); of Lake Pontchartrain; of the Fish River (probably a mistake, for a memoir on the navigation of Lake Pontchartrain mentions the Fish River as lying half-way between Bayou St. John and Manchac); and finally, Bayou Tchoupic of Tchoupicatcha.

At all events, and in spite of generally accepted beliefs, it must not be confounded with the Houmas’ portage, discovered by Le Sueur and lying six leagues farther north. In our opinion, the Houmas did not live near the site of New Orleans, even when the French arrived there. The village of these Indians was not on the shores of Lake Pontchartrain, but “two good leagues and a half away from the river,” according to a letter of Tonty’s; two leagues, according to Iberville; one league and a half from the river and on the crest of a hill, according to Father Gravier. Some little time later, the Houmas emigrated northward and a certain number among them settled not far from the Iberville River, a new portage responsible for additional confusion. In 1718, Bienville wrote: “There are mulberry-trees at New Orleans; the Houma nation, six leagues beyond, can supply some.” (C12c,IV-14.)

As early as 1697, M. de Remonville, returning from a trip to Illinois, had planned with Le Sueur to found a Mississippi Company. He seems to have been the first to think of building a post near site “of New Orleans, to replace the fort established by Iberville in 1700, twenty-five leagues from the river’s mouth, as a protection against a return of the English. This post, surrounded by marshes, was soon neglected and was completely evacuated in 1707, “lacking launches to supply it with food.”

A History of the foundation of New Orleans

Remonville writes, 6th August, 1702, in his Historical Letter Concerning the Mississippi: “The fort which was in (sic) the Mississippi River, eighteen leagues from the mouth on the west side, and which is commanded by M. de St. Denis, a Canadian officer, since the death of M. de Sauvolle (whose place has been taken by M. de Bienville, brother of M. d’Iberville), must also be changed. It should be transferred eleven leagues higher, to the eastward, in a space of land twelve leagues long and two leagues wide (at barely a quarter of a league from the Mississippi, which is very fine) beyond the insulting reach of floods and near a small river. The latter flows into Lake Pontchartrain and, by means of the canal where M. le Sueur passed, joins the sea about a dozen leagues from Mobile. This will make communications much shorter and easier than by sea.” (Bibl. Nat. Mss. Fr. 9097, fol, 127.)

In 1708, Remonville drew up another memoir:

“The first and pricipal establishment ought to be built on high ground dominating Lake Pontchartrain, and in the neighborhood of the spot where the late M. d’Iberville built the original fort. A fort consisting of four buildings is required here, the largest of which can be constructed in the manner of the country, that is, with big trees, turf, and palisades. This fort must be provided with artillery and armed; its area must be sufficient;to enclose warehouses for merchandise drawn from the different establishments up the river. In this same fort, rooms must be built for silk-work to be done by people the company may employ. The Mississippi Fort will need thirty-five workmen, Canadians or sailors, for navigating the brigantines.” (Colonies C13a,2,fo.366.)Reverting to the subject in his Description of the Mississippi, 1715, Remonville wrote:

“Le Sueur relates in his journal that, eleven leagues above the fort built by Iberville, there is a stretch of high ground twelve leagues long and a league and a half wide beginning a quarter of a league from the river; that it can never be flooded, and that a savage nation called the Billocki have transported their village thither, on the banks of a river named the St. John River, which flows into Lake Pontchartrain. A post at this point would not be without utility as warehouse for the projected establishment at Natchez. Twelve leagues higher, there is also the portage of the Le Sueur Ravine.” (Colonies, F3, 24, fol. 81.)

When a party of Alsatian colonists arrived, a few years later, they settled opposite to the last named point.

Ever believing firmly in the future of Louisiana, Remonville crossed to the colony several times. He had secured permission to accompany Iberville in 1699, but it is doubtful if he went on that first expedition. Eventually he built on Dauphin Island a “fine and commodius” house, one room of which long did service as a chapel. In 1711, he fitted out La Renoinmée and took personal charge of her as “Commander during the campaign,” although he was said to know nothing about navigation.

Unfortunately, all his commercial ventures failed. The last of them effected a few captures; one among these, which, according to Remonville himself, had been “pillaged in an almost unprecedented way” was released at Martinique, and the captain was paid an indemnity of fifteen thousand livres or francs; another was lost within sight of Louisiana. The deficit was more than forty thousand livres. Upon his return, creditors seized all his goods and even obtained against him several writs of arrest, from which he escaped, thanks only to a special safe-conduct, granted him by the Council of Regency.

Completely ruined, Remonville asked, and in vain, on the 21st of December, 1717, for a post in Louisiana “because he had been the only one to sacrifice himself to help the colony.” Though the valiant colonist may have proven a mediocre tradesman, he was enterprising, and the services he rendered were very real. But he was not heeded; and in Paris, as in Louisiana, the Mississippi rested under the spell of a detestable reputation.

Mandeville wrote in 1709: “It is easy to go from Fort Mobile to Lake Pontchartrain, and from that lake a portage of one league leads to the Mississippi (sic). By this means, the river is reached without passing through the mouth, which lies twenty-five leagues down a very difficult country, because often flooded and filled with alligators, serpents, and other venimous beasts. Furthermore, at the deepest of the passes there are only seven feet of water.” (Colonies F3,24,fol. 55.)

Another memoir, slightly later says: “The Mississippi does nothing but twist; it goes the rounds of the compass every three leagues. For six months it is a torrent, and for six months the waters are so slow that at many place pirogues can scarcely get past.” Duclos, the Ordinator, declared that to navigate the Mississippi one had to be born a Canadian and a Coureur de Bois.

Finally, La Mothe-Cadillac, who described himself as “a savage born a Frenchman, or rather a Gascon,” wrote on the 20th of February, 1714: “Trying to take barges up the St. Louis River as far as the Wabash and the Missouri is like trying to catch the moon with your teeth.” (C13a,4.424.)

La Mothe-Cadillac, as is known, had rapidly conceived a prejudice against Louisiana; he used to say, “Bad country, bad people.” “I saw,” he related in 1713, “three seedling pear-trees; three apple trees, the same; and a little plum-tree three feet high with seven sorry plums upon it; about thirty vine-plants bearing nine bunches of grapes, each bunch being rotted or dried up. There you have the earthly paradise of M. d’Artaguette, the Pomona of M. de Remonville, and M. de Mandeville’s Islands of the Blest!”

Nevertheless, those responsible in France understood that they could not rest eternally contented with occupying a few sterile sand-banks along the coast. There was no choice but to settle in the Mississippi Valley and connect with Canada. On the 18th of May, 1715, an order was signed directing Bienville to create a post “at the Natkes” (sic) and at Richebourg, and to found another “at the Wabash which shall henceforth be called the St. Jerome River.” According to Father Marest, the Indians called this river Akansca-Scipui.

These decisions followed close upon the return of Baron, Captain of the Atalante, who wrote on the 20th of January, 1715: “The right place for an establishment is the entire length of the river, starting with the Natchez village a hundred leagues from the sea-coast, whither M. de La Loire and his brother were sent in April, 1714, and thence as far as the Illinois country. I have always heard that it is at the said Natchez that the soil begins to be good, which can be judged according to appearances.” (Arch. Hydrog. 672,No. 5.)

At about the same period — the paper is undated — Crozat presented a memoir in which he said:

“The new posts which have been proposed to His Excellency for occupation are, first of all, Biloxi, on the Mississippi, eighteen or twenty leagues from the sea. It is the spot where M. d’Iberville made his first establishment; it is also the spot by which the Mississippi River is reached from Lake Pontchartrain, through a small stream. Furthermore, it is not right that there should be no post on the Mississippi River towards the sea, that of Natchez being sixty leagues away. Twenty men should be put there.”

How little was known of Louisiana geographically in Paris, is shown by this singular document, where three very different posts are confused and located in one same spot; Iberville’s original Biloxi; the Portage of the Mississippi — or of the Biloxi, a nation which, according to Le Maire, had then dwindled to five or six families — and the abandoned Mississippi Fort.

The post demanded by Crozat would necessarily be established on the site of New Orleans. But the project was not ratified; the instructions given to L’Epinay on the 29th of August, 1716, do not mention any post to be created beneath Natchez:

“* * * It would seem absolutely necessary to found a post on the Mississippi and to send thither fwo companies with M. de Bien-ville, King’s Lieutenant, to take command, he being much loved by the savages and knowing how to govern them. From this post, detachments may be made according to necessities for the post to be established on the Red River and the Wabash. There is every reason to believe that this post will be the most important in the colony, owing to the mines which lie not far distant, to the trade overland with Mexico, to the beauty of the climate, and to the excellence of the soil which will induce residents to stay there. This post was ordered to be at Natchez; nevertheless Major de Boisbriant thinks wiser to place it among the Yazoos, on the banks of the Mississippi, thirty leagues beneath Natchez.” (Colonies, C13a,4,fol. 225.)

Three years of experiments had amply sufficed to disgust Crozat with his commercial monopoly in Louisiana. He had counted on two main sources of revenue, mining and a more or less illicit trade with the rich provinces of New Mexico; both had brought in nothing save bitter disappointment.

The Mississippi Valley yielded neither gold nor silver; and, at his first attempt to develop commercial relations, the Spaniards closed their ports to French ships and kept strict watch upon their Texas frontier. Juchereau de St. Denis succeeded, by an adventurous exploring expedition, in going up the Red River and reaching Rio Grande del Norte; but the sole result was the creation of a Spanish post at Assinais, for the special surveyance of trade with our establishment at Natchitoches.

Crozat, perceiving that his privilege cost him at least two hundred and fifty thousand livres a year, took ever less interest in the future of Louisiana; and when January, 1716 came, the Colony’s position appeared desperate. The troops had dwindled to some hundred and twenty men; and if we are to believe Cadillac, there were not more than sixty colonists and officials. Such a handful of Frenchmen could not have defended Louisiana against encroachments of the English, who had already settled as masters among the Choctaws and even among the Natchez. It was well for France that the Carolina traders should, by their exactions, have driven the Indians to an uprising in 1716. The Council of Regency, acquainted with the situation, made the melancholy remark, on the llth of February, 1716, that “if Louisiana has held her own, it is rather by a sort of miracle than by the care of men; the first inhabitants having been abandoned for several years without receiving any assistance.”

When the Justice Chamber imposed a very heavy tax upon Crozat (it was said to exceed six million livres), the great financier asked permission to retrocede his privilege; and on the 13th of January, 1717, the Council recognized “that the improvement of Louisiana was too great an undertaking for one private individual to be left in charge; that the King could not properly take charge himself, since His Majesty could not enter into all the commercial details inseparable from it; and so the best thing is to choose a company powerful enough for this enterprise.” (Marine,B1,19,fol.46.)

Six months later, Law founded the Company of the West, and Crozat eventually received an indemnity of two million livres. The letters patent of the Company were signed in August, and its Directors appointed on the 12th of September, 1717 The Board was composed as follows: Law, Director General of the Bank; Diron d’Artaguette, Collector General at Auch; Duche, Honourary Senior Clerk of the Treasury at La Rochelle; Moreau, Commercial Deputy for St. Malo; Castagniere, Merchant; Piou and Mouchard, Commercial Deputies from Nantes. On the 5th of January, 1718, Raudot, Marine Intendent, and Boivin d’Hardencourt and Gilly de Mon-taud, Merchants, completed the Board.

One of the first acts of the Directors was to decide that New Orleans should be founded.

Le Nouveau Mercure for September, 1717, published a letter from Louisiana, dated the previous May, whose author, a naval officer, recommends the building of a counter at English Turn:

“* * * The largest ships can easily enter the St. Louis River. Its mouth can readily be cleaned, the depth of water is eleven or twelve feet. This obstacle being done away with, the river, whose bed is very good, flows quite straight for twenty-five leagues, and then forms a cove where an excellent port can be made.”

Although this solution recommended itself from a naval point of view, it had the drawback of not improving the connections with Lake Pontchartrain. Wherefore Bienville, after a careful study of the question, preferred to select the present site of New Orleans “on one of the finest crescents of the river.” This expression, found in a memoir drawn up in 1725 or thereabouts, shows that the crescent, which was later to give New Orleans her nickname, had been observed almost from the start. Other references to it are found: “The very fine crescent of the port of New Orleans.” (C13c,1,fol.135). “Her port, which is her richest ornament, describes a very fine crescent.” (C13a,42,fol.295).

In spite of the rather swampy soil, exposed to floods when the river rose, the choice of a site was good, since it lay sufficiently near the sea and less than a league from Bayou St. John, whence all the coast establishments could be reached by boat. The vision of Bienville had been clear, and the nascent colony would have been spared many calamities if stores had been built at New Orleans early in 1718 and colonists had been enabled to land.

But rancourous jealousies, on the part of inhabitants of Mobile and of Biloxi, acted for four years as a check on the new Mississippi counter. In consequence, the growth of Louisiana was arrested.

CHAPTER II.

The Naming and the Foundation of New Orleans

ESIRING

to greet M. de L’Epinay, the new Governor, Bienville came down the river in the spring of 1717. Although appointed the year before, L’Epinay had not hurried to leave France; one of the reasons given for his delays was that he would not sail until a twelvement’s emoluments had been paid him in advance.

ESIRING

to greet M. de L’Epinay, the new Governor, Bienville came down the river in the spring of 1717. Although appointed the year before, L’Epinay had not hurried to leave France; one of the reasons given for his delays was that he would not sail until a twelvement’s emoluments had been paid him in advance.

According to Father Charlevoix, this event serves to determine the period when the site for New Orleans was definitely chosen. “In that year,” he writes, “the foundation of Louisiana’s capital was laid. M. de Bienville, having come from Natchez to greet the new Governor, told him that he had noticed, on the river-banks, a very favourable site for a new post.” (Histoire et description de la Nouvelle France, Vol. IV, p. 196.)

This version may pass all the more readily, at least in substance, since Bienville wrote on the 10th of May, 1717: “I have handed to M. de L’Epinay a memoir on all the establishments which must be built in this country. He asked me for it in order that he might send it to the Board. I take the liberty of assuming that I said in this memoir all there was to be said, very sincerely and in accordance with the knowledge I have acquired during nearly twenty years.” (Arch. Nat., Colonies, C13a,4,fol. 63.) Unfortunately, we have not been able to find this document.

It is an incontestible fact that on the 1st of October, 1717, the Marine Board appointed Bonnaud store-keeper and cashier, with a salary of nine hundred livres, at the counter which is to be established at New Orleans, on the St. Louis River.” Colonies, B42bis.fol. 180.) On the 31st of December following, M. d’Ayril, former captain of the Royal Bavière, was named Major at the new post. “Be it further understood,” his nomination reads, “that in the absence of the Commandant of the said city, you shall command as well the inhabitants thereof as the warriors who are there and may later be garrisoned there; and shall give them such orders as you may judge necessary and appropriate for the glory of His Majesty’s name, the welfare of the Company’s service, and the maintenance and development of its trade in the said country.” (Colonies,B 42bis, 475, and f324, fol. 241.) Three months later, d’Avril was promoted Major-General with a salary of seven hundred livres. At the end of three years, he was recalled, and left Louisiana on the 8th of January, 1721.

The appointment of Bonnaud, signed on the 1st of October, only three days after that of Bienville as “Commander General of the Louisiana Company,” shows the haste of the Directors to found the New Orleans post, at least theoretically. Hopes of promoting the sale of the Company’s paper, then representing sixty-six million livres, as issued on the 19th of September, certainly played a part in this precipitation. Within three months, the Company’s capital was raised to one hundred million livres.

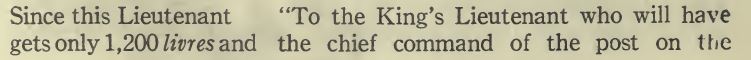

A register which must have belonged to a Director of the Company of the Indies contains copies of “orders and expenses of the Company of the West, from the time of its foundation until this day.” It is to be regretted that in this manuscript, which ends with the year 1721, many of the entries are left undated.

“* * * 8th. Resolved to establish a port and a store at Ship Island to unload and warehouse merchandise coming from Europe, because this island is within reach of Biloxi, the naval centre of the Colony.

“9th. Resolved to establish, thirty leagues up the river, a burg which should be called New Orleans, where landing would be possible from either the river or Lake Pontchartrain.”

The decrees which follow prescribe the establishing of a burg at Natchez, and of forts in Illinois and among the Natchitoches.

Since the conditional mood was used in alluding to New Orleans, it might appear that this was the first decree relative to the projected town. And yet, in the chapter on increases of expenses proposed for 1717, the following entries are to be noted:

The Louisiana Budget passed, in 1717, from 114,382 livres to 262,427 livres; 65,545 l. were entered as permanent increases, and 82,500 l. as “expenses made once and for all.”

When this statement .of expenses was drawn up, the Mississippi post was still unbaptised, in spite of its recognised importance. The name of New Orleans was certainly known in Paris at the end of September, 1717; and we have reason to believe it must have been current in Louisiana at the same period. On the 1st of September, L’Epinay and Hubert announce “the early foundation of two posts,” and a memoir drawn up by Hubert, preserved at the Ministry of Foreign’affairs, declares: “New Orleans, which is to be the naval centre, must be properly fortified.” Nevertheless, it makes a reference to another memoir, of the month of October, which it compliments and in which we read “the establishments are too far from the Mississippi, a river supplying an excellent base.” There cannot be much difference in date between the two, and we even believe they went by the same mail. Hubert, who had asked to be appointed manager of the Missouri post, changed his mind as soon as he had secured a concession in the Natchez country.

Considering the slowness of communications at that period, we are of the opinion that New Orleans must have been given its name not by the Marine Board, nor by the directors of the Company of the West, but by Bienville and L’Epinay, in their report of May, 1717, on the new posts to be established.

The names chosen for many previous posts in Louisiana had been scarcely attractive. Mobile appeared to cast reflections on its own stability; the still widely-used name of Massacre Island was calculated to alarm timid souls; while Biloxi and Natchitoches struck Parisian ears as being very exotic. Bienville had perceived this. In 1711 he wrote that he had, together with D’Artaguette, “called the fort Immobile, and changed Massacre Island to Dauphin Island.” On the margin of their despatch is noted: “Fort St. Louis as it was called — instead of Castel Dauphin or Mount Dauphin; the island is on a mountain (sic).” In July, 1717, the Marine Board considered the names of Maurice Island, or Orleans Island.

A town baptised in honour of H. R. H. the Regent could not but make a favourable impression upon emigrants. Such august patronage inspired confidence to Le Page du Pratz and twenty other colonists, who decided to embark for the new city, at the beginning of 1718. When starting forth, these worthy people, and the two functionaries already appointed to New Orleans, cannot have had a very clear idea on the location of their future residence. Many opinions were expressed in Paris. Some claimed that the new counter must be at English Turn, others on Lake Pontchartrain, others at the mouth of Bayou St. John; or again, somewhere along the Iberville River.

For a considerable time these geographical questions remained unsettled, so far as France was concerned. Harmony did not reign even for the spelling of recognised names. The strange orthography “L’Allouisiane” is found fairly often, nobtaly in an admirably penned memoir preserved at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In other official records we find “Louisianne” and “Louizianne.” A despatch of D’Artaguette’s is annotated: “Investigate whether this River of the Maubilians is not the Colbert River.” As we have said, Biloxi was frequently confused with the portage of Bayou St. John, at first known as the Portage of the Billochis; another frequent error was to place the Mississippi Islands at the river’s mouth.

The Mississippi Counter had been baptised, and this was a point of crucial importance to bureaucratic eyes. But, as has been remarked, the title is half the whole book; and so the Directors of the Company, aftei approving the name, rested for four years.

Purists found objections to raise. “Those who coined the name Nouvelle Orleans,” Father Charlevoix observes, “must have thought that Orleans was of the feminine gender. But what does it matter? The custom is established, and custom rises above grammar.”

His remark is just. The general rule, in French, is for names of towns to be masculine when they are derived from a foreign masculine or neater names, or, more simply, when the last syllable is masculine according to the rules of versification. Yet there are exceptions; thus Londres is masculine and Moscou feminine.

If both custom and derivation were strictly respected, Orleans (Aurelianum) would incontestibly be masculine, although Casimir Delavigne has written:

Chante, heureuse Orleans, les vengeurs de la France.

The reason for the feminising of New Orleans was probably euphonic. Nouvean-Orléans would have been too offensive to the ear. It is true that Nouvel-Orléans might have passed. Perhaps Nouvelle-Orléans was adopted by analogy with Nouvelle-France, Nouvelle-York, etc.

A more delicate question is that of determining the exact period when work on New Orleans was begun. According to Father Charlevoix, it started as early as 1717.

“M. de L’Epinay,” he says, “commissioned M. de Bienville for this establishment, and gave him eighty illicit salt-makers, recently arrived from France, with carpenters to build a few houses. He also sent M. Blondel to replace Pailloux at Natchez, and the latter was ordered to rejoin M. de Bienville and second him in his enterprise, which was not carried very far. M. de Pailloux was appointed Governor to the nascent town.” On the Statement of Expenses for 1718, Pailloux is entered as Major-General with a salary of nine hundred livres. (Colonies, B. 42 bis, fol. 299.)

The evidence of the historian of New France would merit serious consideration, if he had not copied this passage textually, with one correction, from a very unreliable manuscript entitled Relation ou annale dc ce qui s’est passe en Louisiane (Bibl. Nat., Mss. Fr. 14613), for which Andre Pénicaut supplied the information.

This work on the foundation of New Orleans is filled with errors so gross that they would be incomprehensible, if they were not evidently deliberate. In 1723, the unhappy carpenter had gone blind, and his Relation is really but an explanatory memoir to justify his request for a pension. Under these conditions, the author would have blundered if he had described the true state of the future capital when he left it in 1721. Governor La Mothe-Cadillac was sent to sojourn in the Bastille with his son, for having written: “This Colony is a beast without either head or tail. * * * * The Arkansas mines are a dream, and the country’s fertile lands an illusion.”

Consequently, Pénicaut cannot be blamed if some of his-descriptions are so fanciful as to be worthy of a Rue Quincampoix circular. The author’s motive in advancing by a year the foundation of New Orleans is less easily explained. According to the sequence of events as given in the Relation, and notably the arrival of the Neptune, Pénicaut would appear to have confused the choice of a site for New Orleans with the building of the first huts. But most of his dates are inaccurate, his work having been compiled from memory.

JEAN-BAPTISTE LE MOYNE DE BIENVILLE (1680-1765}

Bénard de La Harpe, in his Journal de voyage de la Louisiane et des découvertes qu’il a faites, gives the date of March, 1718; nevertheless, the author had not reached Louisiana, so his opinion has not the weight of direct evidence. The work entitled Journal historique de l’Etablissement des Français en Louisiane, wrongly attributed to La Harpe and very probably written by the Chevalier de Beaurain, King’s Geographer, gives February as the approximate period.

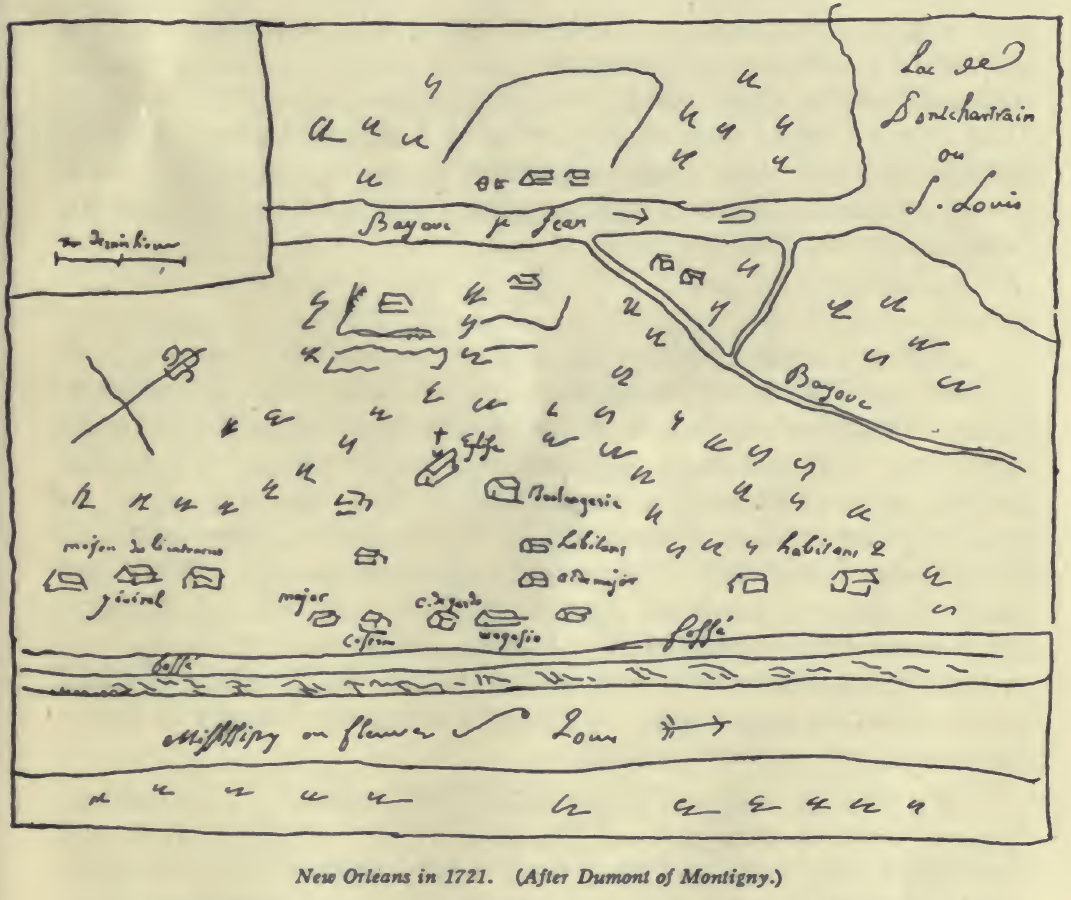

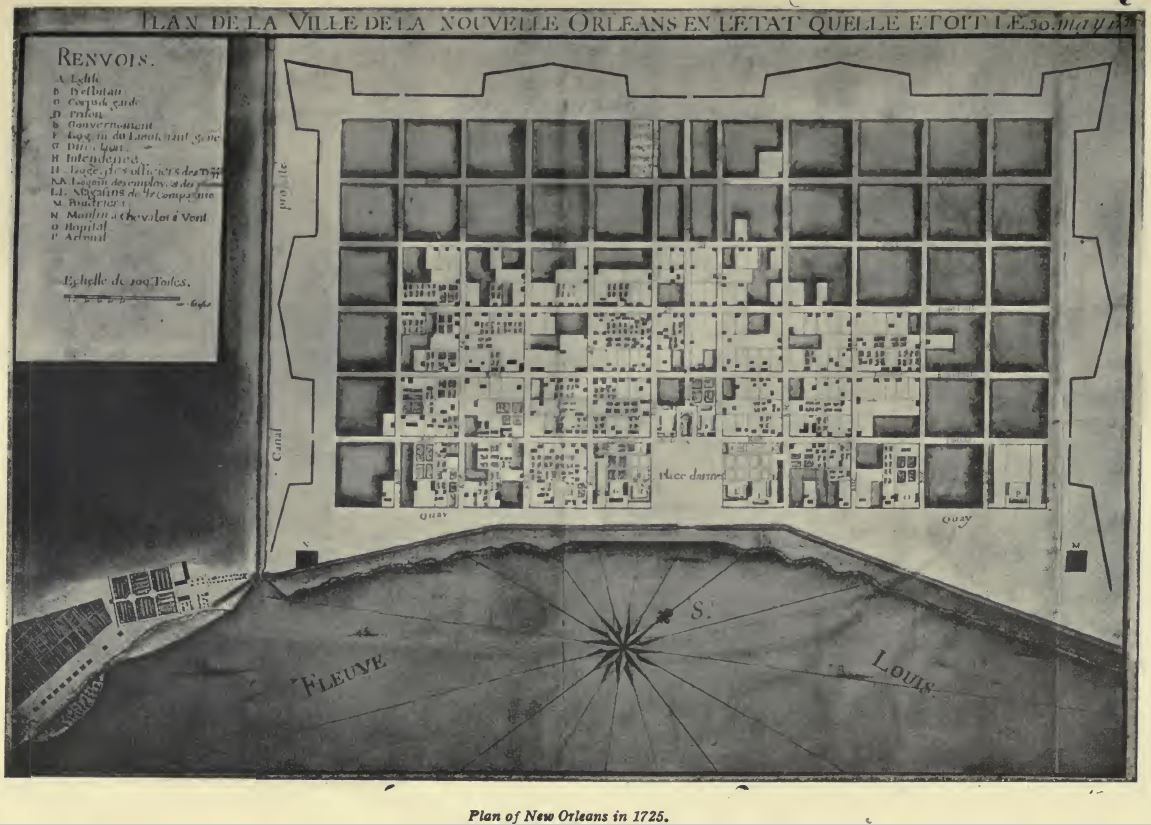

La Harpe writes: “In the month of March, 1718, the New Orleans establishment was begun. It is situated at 29°50′, in flat and swampy ground fit only for growing rice; river water filters through under the soil, and crayfish abound, so that tobacco and vegetables are hard to raise. There are frequent fogs, and the land being thickly wooded and covered with canebrakes, the air is fever-laden and an infinity of mosquitoes cause further inconvenience in summer. The Company’s project was, it seems, to build the town between the Mississippi and the St. John river which empties into Lake Pontchartrain; the ground there is higher than on the banks of the Mississippi. This river is at a distance of one league from Bayou St. John, and the latter brook is a league and half from the Lake. A canal joining the Mississippi with the Lake has been planned which would be very useful even though this place served only as warehouse and the principal establishment were made at Natchez. The advantage of this port is that ships of .... (left blank) tons can easily reach it.” (P. 81.)

If the building of New Orleans did not begin in March, it was certainly put under way the following month. Bienville writes, 10th of June, 1718: “We are working on New Orleans with such diligence as the dearth of workmen will allow. I myself went to the spot, to choose the best site. I remained for ten days, to hurry on the work, and was grieved to see so few people engaged on a task which required at least a hundred times the number. . . . All the ground of the site, except the borders which are drowned by floods, is very good, and everything will grow there.” (Archives des Aff. Etrang., Mém. et Docum. (Amérique) Vol. I; p. 200.)

Four days previously, in a despatch of which the summary alone remains, Bienville had proposed the digging of a canal between the Mississippi and Lake Pontchartrain, for purposes of sanitation, but had added: “It is more convenient to pass through the mouth than through the Lake.” (Arch. Nat., Colonies, C13c, 4, fol. 14.) In the preceding January, Chateaugue had reported that “the sea is often dangerous on Lake Pontchartrain, and the squalls are violent.”

The date for the first work done on New Orleans lies, then, between the 15th of March and the 15th of April, 1718. But in spite of Bienville’s efforts, and owing to hostility from “the Maubilians,” the buildings made but slow progress. Le Gac was justified in writing in his Mémoire sur la situation de la Louisiane le 25 août 1718: “New Orleans is being scarcely more than shaped.” (Bibl. de l’Institut, Mss. 487, fol. 509.)

For a long while, adversaries of the Mississippi Counter adopted the tactics of refusing to recognize its existence.

François Le Maire, the geographer-missionary, particularly distinguished himself by his obstinacy. He felt able to write, as late as the 13th of May, 1718: “Since the last ships came, there is talk of the establishment to be made at New Orleans. That is the name recently given to the space enclosed between the Mississippi, the Fish River, and Lakes Pontchartrain and Maurepas. My map shows distinctly this big spot on the coast, and the lay of the land. I should have liked to mark the place where the fort is planned, but the place is not yet decided upon. This establishment will be excellent, provided the Mississippi is made to empty into Lake Pontchartrain. Otherwise an infinity of people will die from lack of water fit for drinking most of the year.” (Arch. Hydrog. 67, No. 15.) Six months later, however, Le Maire repeats in his Mémoire sur la Louisiane: “At the end of this year (1718) orders came to transfer the principal establishment to the banks of the Mississippi. If the spot is decided upon before the ships leave, I shall not fail to mark it on my map.” (Colonies, C13c, 4, fol. 155.) One might seek to explain this by an error in dates, if the Grand Vicar of the Bishop of Quebec had not supplied further evidence, on the 19th of May, 1719: “The precise bearings of New Orleans, in relation to Lake Pontchartrain, are still unknown to me.” (Arch. Hydrog., 115, 23.)

Le Maire’s ill-will is only the more evident because he constantly betrays the hope that New Orleans may be created on Lake Pontchartrain, so that its counter may be tributary to Biloxi. In another very detailed memoir, while acknowledging that “the Mississippi is the key to the entire country, thanks to the communications it offers with the lakes leading to Canada,” he nevertheless asserts that no port exists between St. Bernards’ Bay and Ship Island. (Colonies. C13c, 2, fol. 161.)

We have not been able to ascertain the period at which Delisle added the name of New Orleans to his map dated 1718. The vivid Relation du voyage des dames Ursulines de Rouen a la Nouvelle Orleans, informs us that in 1727 most maps of America still failed to give the site of Louisiana’s capital.

“You note, dear Father,” Madeleine Hachard writes, “that you have bought two big maps of the State of Mississippi and that you do not find New Orleans on them. They are apparently old, for this town, capital of the country, should not have been omitted. I regret that you spent one hundred and ten sols without finding our place of residence. I believe new maps are to be made, on which the establishment will be marked.”

The good nun’s father was veritably unlucky; he bought a third map “on which New Orleans is represented upon the shores of Lake Pontchartrain, at a distance of six leagues from the Mississippi.”

A map still preserved at the Archives Hydrographiques, dated 1721, indicates the mouth of Bayou St. John as the site for the future capital. (Arch. Hydrog., portfolio 138 bis, I, 9.)

Let us now return to the foundation of New Orleans, quoting from worthy Pénicaut. After declaring that “the first year only a few lodgings, and two big stores for war supplies and general provisions, were built,” and adding, more truthfully, that “the Neptune (arrived in 1718) was brought into the river, laden with munitions sent by M. de L’Epinay,” he or his editor yields to astonishing freaks of fancy:

“M. the Commissary Hubert also went at the same time to New Orleans, through Lake Pontchartrain, into which flows a little river since called the Orleans River. It may be followed from the Lake to this place, within three quarters of a league. A few days after his arrival, M. Hubert selected a spot situated at a distance of two gunshots from the limits of New Orleans, near the little river of the same name, where he built a very fine house. Several families living on Dauphin Island also came to settle in New Orleans. M. de L’Epinay and de Bienville sent many soldiers and workmen thither to hurry on the building. They despatched to M. de Pailloux an order to erect two barracks large enough to hold one thousand soldiers apiece (!) because many were expected from France that year, in addition to a number of families from neighboring concessions. All this came about, as stated.”

The plain truth, alas! was less attractive. In March, 1719, one year after work commenced, there were still, according to Bienville, “only four houses under way“ (Colonies, C13a, 5, fol. 209.) When Hubert, appointed on the 14th of March, 1718, as “Director General of the New Orleans Counter,” with a salary of five thousand livres, rejoined his post in the autumn, far from “building a very fine house,” his first care, as soon as a few colonists came, was to induce them to settle at Natchez, where he had just obtained a very large concession.

And yet, Hubert was forced to countersign, on the 28th of November, 1718, Bienville’s decision, confirmed on the 12th of September, 1719, by Le Gac and Villardeau, “granting to the Sieurs Delaire, Chastaing, and Delaroue in addition to their concession in the Taensas’ country * * * four places within the enclosure of the new town of Orleans, as their exclusive freehold property * * * it being stipulated that they shall execute all the clauses and conditions prescribed for inhabitants of the new town.” (Colonies, C13, 4, fol. 216.)

If Bienville and Pailloux were the first residents in New Orleans, the honour of being the first landowners reverts to the Delaire Brothers, Chastaing, and Delaroue. A map preserved at the Archives Hydrographiques, Carte nouvelle trés exacte d’unepartie de la Louisiane, 1718, indeed bears the mention: “New Orleans, founded in 1718 by the Sieur Pradel.” (Arch. Hydrog., Bibl. 4040, C. II, fol. 6.) But this is evidently a mistake attributable to the confusion of New Orleans with Fort Orleans on the Missouri, to whose establishment Pradel contributed in 1724, under Bourgmont’s orders.

We have not yet described the arrival of the Neptune and of the Vigilante at New Orleans, because there is reason to ask whether these ships did not really unload at English Turn, where, according to the seemingly reliable document which we reproduce (see p... ), a large store had been built at this time.

The instructions handed to Beranger on the 1st of October, 1717, specify: “* * * When he reaches Louisiana, he will receive orders from M. Hubert, for going up the Mississippi River; the brigatine Le Neptune being affected to navigating the river, the Company intends him if possible to go to Illinois, and he shall use every means for getting there.” This shows the illusions entertained in Paris about the navigability of the Mississippi. Nevertheless, we are all the more inclined to believe that the Neptune did not go so far as New Orleans, in 1718, since Beranger, in sundry memoirs, while admitting that he has piloted several vessels in the river, declared for a long time that none could sail up to New Orleans.

Although Louisiana paid small attention to the new counter, Paris devoted much thought to it, while reaching no definite opinion as to a suitable locality. The instructions delivered by the Company to Chief Engineer Perrier, on the 14th of April, 1718, allowed him utmost latitude for the choice of a site:

“Ascending the river to the point which Messrs, the Directors-General may judge proper for laying the first foundations of New Orleans, he must take the best map he can of the river’s course. . . . We do not know what place will be selected, but since the said Sieur Perrier is to be present at the council held for this purpose, he must be made to understand the leading considerations.

“The chief among these is to find the most convenient place for trading with Mobile, whether by sea or by Lake Pontchartrain, which place must be in the least danger from inundation when floods occur, and as near as possible to the best agricultural lands.

“These various considerations convince us, as far as we can judge, that the most convenient site is on the Manchac brook; the town limits should stretch from the river-banks to the edge of the brook. This spot must be examined to see if the land is suitable, before any definite choice is made. If it is suitable, then New Orleans will be better there than elsewhere, because of the convenience for communications with Mobile by the brook, which is reported as navigable at all times and at slight expense, and because it is within reach of the entrance to Red River. Thence communication may be had with the plantations to be formed in the Yazoos’ country, where we expect wheat to be first planted — it may even thrive there, eventually. Furthermore, the spot mentioned is well inland; and then, hunting affords abundant means for subsistence, and the healthiness of the air can be relied upon.

“The sole difficulty remaining before New Orleans can be built on the Manchac brook, is its distance from the sea, sixty-five leagues. If, however, ships can readily sail up so far, and it is only a question of a few days more or less, this is not an obstacle to outweigh other advantages. Ships do not come every day, and the other conveniences are enjoyed the year round. But, at the same time, care must be taken, in going up the river, to choose the most suitable place, perhaps English Turn, for establishing a battery in a small fort which may prevent hostile ships from ascending.

“* * * When the site for New Orleans has been determined, we presume the said Sieur Perrier will begin by marking out the limits of a fort which may later become a citadel, but which at first need simply to shut in with stockade, after the manner of the country. Here the Company’s stores shall be situated and lodgings for the Directors-General, commanding officers, officers, and soldiers forming the New Orleans garrison. This being done, the Sieur Perrier shall trace out the town limits and the alignment of streets, with the size of lots suitable for each resident of the town, Messrs. the Directors-General having the privilege to allow them near-by lands for cultivation. Once the men are lodged, the most pressing need is for storehouses. We can make no prescriptions as to the extent of these or the manner of their building, questions which Messrs, the Directors-General must settle with M. Perrier. We merely recommend to his attention that during his stay at Dauphin Island and in Mobile, he must collect whatever he can find in the way of planks, hoarding, and scantling, so that he may use them upon reaching New Orleans.

“There is a project to start work by throwing up rough shelters for both men and goods. But this should not prevent the said Sieur Perrier from seeking at the same time the best means to obtain materials for permanent building. To this end, he shall erect, as soon as possible, a brick manufactory, if the soil in or near New Orleans is suitable. Soldiers or illicit salt-makers who understand brick-making could be employed; or else we shall end over a brick-maker by the first ships. In the case we are unable to find others to sail with him, we are sending bricks in the three ships with which he sails; he shall have a care to save them for building the first kiln.

“These first measures being taken, he must go himself to seek, in the neighbourhood of New Orleans, places where stone may be had for purposes of toth building and chalk-making. It is not impossible some may be discovered. He must particularly exert himself to find it on the river-banks, as he goes up, so that transportation may cost less; and as promptly as possible, so that the buildings may be stone and brick, which is best * * *" (Colonies, B. 42 bis, fol. 219.)

On the 23rd of April, the Company appointed Bivard surgeon to New Orleans, with a salary of six hundred livres; and on the 28th, concessions near the new establishment were granted to twelve persons. Amoug these pioneer citizens were: Le Page du Pratz, the future historian of Louisiana, Le Goy, Pigeon, Rouge, Richard Duhamel, Beignot, Dufour, Marlot de frouille, Legras, Couturier, Pierre Robert, the three Drissant brothers, Bivard the surgeon, and Mircou the perruquier. With their families and retainers, they formed a band of sixty-eight people. (Colonies, B. 42 bis, fol. 252.)

When announcing their departure, the Company added: “If possible, they must be compelled to dwell within the limits of New Orleans, having only gardens there, as may be decreed, and receiving grants or lands as near as may be, in proportion to their strength.” The managers furthermore directed that two soldiers from each of the eight companies should be released on condition they went to live in New Orleans; they were to receive a year’s pay, besides tools and seeds.

Perrier’s death, which occurred in Havana, allowed Hubert to interpret these instructions at will; he sent off the colonists as far as he could from the new post, and all the workmen who had not deserted were soon called back to Biloxi on one pretext or another.

When Le Page du Pratz landed in January, 1719, he perceived “on the spot where the capital was to have been founded, only a place marked by a palmetto-thatched hut, which M. de Bienville had built for himself and where his successor, M. de Pailloux, lived.” (Histoire de la Louisiane, Vol. I, p. 83.)

All of Bienville’s efforts had been paralysed by the ill-will which the other members of the Board displayed. With his exception alone, they were interested in ventures at the old-trading posts, they would tolerate no word about New Orleans, and they encouraged the coalition of Mobile colonists, of Biloxi tradesmen, and of Lake Pontchartrain boatmen whose business was threatened by rivalry from the Mississippi.

As has been said, Hubert owned a large plantation at Natchez, near St. Catherine’s; in 1820, he had eighty slaves there, and twenty head of horned cattle. The year following, he sold it to Dumanoir. But meanwhile, he asked for the concession of Cat Island, between Biloxi and the entrance to Lake Borgne, “for the raising of rabbits”; and he proposed to found the Mississippi Counter at Natchez and to drag the Iberville River, so that residents in Biloxi might retain their rich monopoly for trans-shipping and warehousing all merchandise from Europe. Nevertheless, Hubert had at first been a partisan of New Orleans: we have seen how he had declared it “must be properly fortified”; in October, 1719, he wrote: “The reason for making a colony of Louisiana was doubtless to become masters of the Mississippi and to occupy it * * * And yet the contrary was done, that great river has been abandoned for the Mobile River.” But as soon as he had secured his concession at Natchez, his opinions underwent a radical change, and a year later he stated: “The difficulties of the lower river will prevent New Orleans from ever being a safe post.”

Duclos judged that “instead of thinking of the Mississippi, all efforts should be directed towards the Mobile River,” which, Du Gac added, must remain “the master-key to the colony.” An earlier memoir, drawn up by M. de Granville, Captain of La Renommée, even urged that the chief establishment be built at “Fort Esquinoque” (probably Tombigbee) among the “Jatas” (Choctaws) sixty leagues from Mobile. As for Larcebault, he considered New Orleans “a submerged country, all chopped with cypress swamps”; and Villar-deau shared his opinion.

After Hubert, Le Gac seems to have been the most inveterate adversary of New Orleans. “This post,” he wrote in 1721, “is flooded when the waters rise, and is fit only for rice, silk, maize, and all sorts of vetgetables and fruit-trees. Tobacco may also be grown.” In spite of which fertility, he concludes that, although a company may be supported there, a counter must not be established at any price.

Profiting by the fact that Boisbriant had left in a very bad season, Le Gac hastened to write to Paris: “M. de Boisbriant, with his company of settlers, employes, and convicts, took more than six months to reach Illinois, because they had to winter in Arkansas. Ice on the Wabash delayed them and they could not do more than four or five hours of rowing from sunrise to sunset, owing to the swift current. Towing is impossible, because the river twists all the way. * * * The banks are covered with impenetrable woods and canebrakes * * * whereas Canadians have gone overland from Illinois to Mobile in less than a month. These assert that the distance was not more than seventy leagues (in reality, two hundred and fifty) whereas it is nearly five hundred by the river and takes five or six months. Trees should be blazed on both sides so that a way may be made and recognized, and establishments should be built from place to place, to serve as retreats; the inhabitants could grow crops and raise animals to supply travellers with food * * * Only causeways and bridges would have to be built, here and there * * *”

In spite of its extravagance, this project was adopted for sometime by the Company of the Indies; but the Chickasaws soon closed the way to the most intrepid coureurs de bois.

New Orleans had none the less demonstrated its utility, from the very start; Boisbriant, with the several hundred soldiers and more or less voluntary colonists he was taking to Illinois, had found shelter there while waiting for ships to be got ready. Bienville and Hubert spent the autumn in New Orleans, to supervise the outfitting of this expedition.

Bénard de La Harpe, accompanied by a non-commissioned officer and six men, came on the 7th of November, 1718, to complete his preparations for a voyage to the Cododaquis Indians on the Red River. Finding at Dauphin Island no means of transportation for his trading goods as far as New Orleans, he had been forced to build a boat at his own expense and go through the mouth of the Mississippi. La Harpe finally arrived safe and sound; nevertheless, his pilot being entirely inexperienced, he ran considerable dangers in the passes of the river, and took a month for the journey.

“As soon as I reached New Orleans,” he states in his Journal de voyage de la Louisiane, “I urged M. de Bienville to get me started off again. He represented to me that he had no provisions in the stores, and that the Company was in no present condition to make good its obligations to convey me at its expense, with my people and my goods to the place where I was to choose my concession on the Red River.”

La Harpe, who had already done much travelling in South America, where he had even found a wife, managed to leave on the 12th of December, in spite of the Mississippi’s strong current.

At about the same period, Dubuisson landed with his silk-growers; but, as Le Gac did not fail to observe, “he settled twenty-five leagues up the river (at Bayagoula).” Le Page du Pratz was among the few to elect a residence, though transitorily, on the banks of Bayou St. John.

CHAPTER III.

The Mississippi Flood in 1719. Consequences of the Capture of Pensacola. The Year 1720.

UCK

still did not favour New Orleans; the year 1719 brought no improvement in the state of stagnation which had become peculiar to the town. An altogether abnormal rise of the Mississippi — the Indians did not remember having ever seen its like — submerged the site, which remained swampy until a dike was built.

UCK

still did not favour New Orleans; the year 1719 brought no improvement in the state of stagnation which had become peculiar to the town. An altogether abnormal rise of the Mississippi — the Indians did not remember having ever seen its like — submerged the site, which remained swampy until a dike was built.

Coast residents made the best of this misfortune, exaggerating it to their own advantage. We may note in this connection that the 1721 flood of the Mobile River, which devastated all the plantations of that region and caused far graver material damage than had been noted in New Orleans two years before, passed almost unperceived at Paris, because there were no interested parties to exploit it against Mobile.

Bienville himself seems to have allowed his faith to be shaken, for a while. On the 15th of April, 1719, he countersigned a despatch of Larcebault’s stating: “It may be difficult to maintain a town at New Orleans; the site is drowned under half a foot of water. The sole remedy will be to build levees and dig the projected canal from the Mississippi to Lake Pontchartrain. There would be half a league of cutting to do.”

Certainly a flood was a disagreeable event, whether the depth of water were really “half a foot” or only three or four inches, as stated in the census of the 24th of November, 1721, signed by Bienville, Diron d’Artaguette, La Tour, De Lorme, and Duvergier. (Colonies, G., 464) But this bore very slight resemblance to the catastrophe over which the members of 1 the Colonial Board wept crocodile tears. Nor does it appear likely that the flood persisted for “six months.”

Hubert promptly turned the situation to his advantage, by transferring to Natchez most of the stores warehoused at New Orleans. “The flood,” he wrote, “compelled all the residents to go to Natchez, where the land lies higher and the heat is less severe.” But since the garrison and several clerks remained at their posts, this picture of a general exodus is overdrawn, to say the least.

Le Page du Pratz, who had settled half a league from New Orleans, does not even mention this terrible flood. He observes that “the country being decidedly aquatic, the air cannot have been of the best,” but adds: “The soil was very good, and I was happy on my plantation.” Du Pratz acknowledges that he had no particular motives in moving to Natchez, unless that his surgeon was going, that his Indian maid wished to be near her family, and that he complied with Hubert’s advice and acted “from friendship for him.”

Pellerin, one of the most enterprising among the colonists, wished to settle near New Orleans, in spite of the flood; he camped on the banks of Bayou St. John in April, 1719. As soon as he had found a good site, he asked for a concession. But Hubert put so many obstacles in his way that he, too, ended by settling at Natchez. He wrote: “There are in New Orleans three Canadian houses and a store belonging to the Company, where we stopped.” (Arsenal, Mss. 4497, fol. 54.) This confirms the figures given by Bienville, who mentioned four dwellings. To get to Natchez, Pellerin passed through the lakes, reaching the Mississippi after thirteen days.

Even when flooded, New Orleans was so far from being uninhabitable that on the 23rd of April, 1719, the Board decided to send thither a clerk “to sell wine at four reals per pint.” A few days before, the Company had fixed as follows the salaries for officials at the new counter: Hubert, Director, five thousand livres. A storekeeper, nine hundred livres. An accountant six hundred limes. A clerk, four hundred livres. These last had under their orders “two men-of-all-work, to be chosen among the illicit salt-makers or tobacco-smugglers, without wages but supplied with rations.” The salary of “the missionary to be sent to New Orleans” was fixed first at four hundred livres, afterwards raised to five hundred. The gunner received three hundred and sixty livres.

M. de Bannez, appointed Lieutenant on the 28th of October, 1717, embarked in May 1719 on the Marie, with Dumont de Montigny Louisiana’a poet-historian. According to certain records, Bannez started out with the rank of Major-General of New Orleans; according to others, he was named to this post only on the 23rd of March, 1720.

The flood having subsided, public attention was deflected from the Mississippi posts. Pensacola was taken, lost, and recaptured.

The certainty that the famous Illinois mines did not exist, or could never be worked, caused keen disappointment. It is worth noting that a memoir preserved at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs recommends using “for the discovery of these mines, wands fitted with electron, mercury, and marcasites on which the heat of the air acts.” (Mém. et Doc. Amér. Vol. I, fol. 433.)

Even the most blindly prejudiced among the colonists should have understood the urgent need for organising their chief warehouse at a sufficient distance from the sea to protect it against sudden attacks. Dauphin Island had been sacked, and other establishments too near the coast had run similar risks; these examples should have sufficed as lessons. Yet the adversaries of New Orleans brought contrary influence to bear. The Company, while changing its name to Company of the Indies, had kept the Mississippi on its arms; but had decided to make Pensacola the main port of Louisiana, regardless of the facts that this town, whose strategic importance was unquestionable, yet suffered extreme disadvantages for trade with the Mississippi, the recognized centre of the Colony. Taking no heed for the expense incidental to trans-shipments of goods, the residents of Biloxi wished to keep ships out of the river and so retain their profits from the unseaworthy sloops of Lake Pontchartrain. If Pensacola had not been restored to the Spanish, merchandise from Illinois would have had not one single transshipment at New Orleans, but four: at Pensacola, at Biloxi, at Bayou St. John or Manchac, and finally on the banks of the Mississippi.

A further drawback to Pensacola as chief stronghold for the Colony was its position on the easternmost frontier of France’s possessions. To assure the defence of Louisiana, it was decided in Paris to build another establishment near the indeterminate limits of New Mexico. Two expeditions went forth in 1720 and 1721, having as mission to occupy mysterious “St. Bernard’s Bay.” Both failed for sundry reasons, foremost among which was certainly the disfavour with which the Colonial Board, now supported by Bienville, viewed settlements along the coast. Saujon complained, on the 23rd of June, 1720, that Bienville and his brother Serigny had prevented him from seizing St. Joseph’s Bay, in Florida. (Marine, B4, 37, fol. 405.)

News of the 1719 flood contributed to the decision reached by the Company of the Indies that work on New Orleans should be suspended. Nevertheless, the occupation of Pensacola, and then hope of occupying the vast Texan territories, discovered by La Salle in the previous century, must have been the leading motives for the incomprehensible desertion of New Orleans during nearly three years.

The illusion that Pensacola might be retained was long cherished in Paris; Engineer-in-Chief LaTour was ordered to settle at that post, according to the first instructions drawn up for him. (B, 42 bis, 3080 But when, on the 20th of August, 1720, the order was signed for restoring the place to the Spanish, the Company, forced to fall back upon the Mississippi, at least acted promptly. Four month later, New Orleans became the capital of Louisiana.

For a few weeks thereafter New Orleans succeeded in meriting the name of “burg,” but this prosperity seems to have been shortlived. During most of the year 1721, the town cannot be said to have done more than manage to exist.

Such were the difficulties incidental to navigating the Iberville River, practically dry for half the year, that all boats passed through Bayou St. John.

“This river,” says an anonymous memoir, “has three feet and a half of water; boats can go up for two leagues, where there are several French planters and a store. Merchandise is landed here and must be conveyed by truck to New Orleans, three quarters of a league distance.” (C13c, 2, fol. 170.)

And yet, no one dared settle at New Orleans, for fear of Hubert and Le Gac. The few who came, left rapidly, like Le Page du Pratz and Pellerin, or withdrew to a respectful distance from the forbidden centre, like du Breuil, du Hamel, the Chauvins, etc.

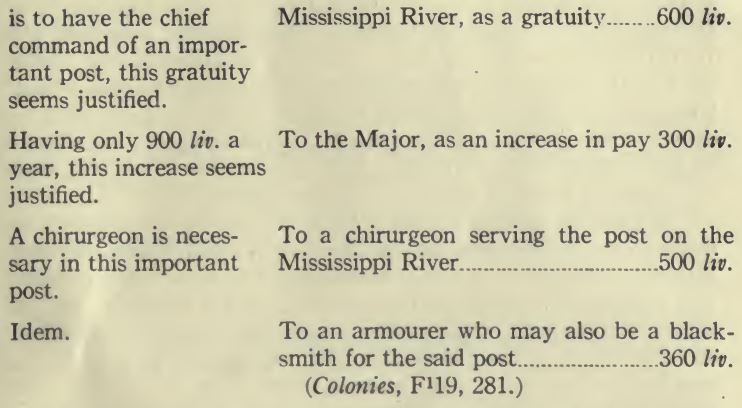

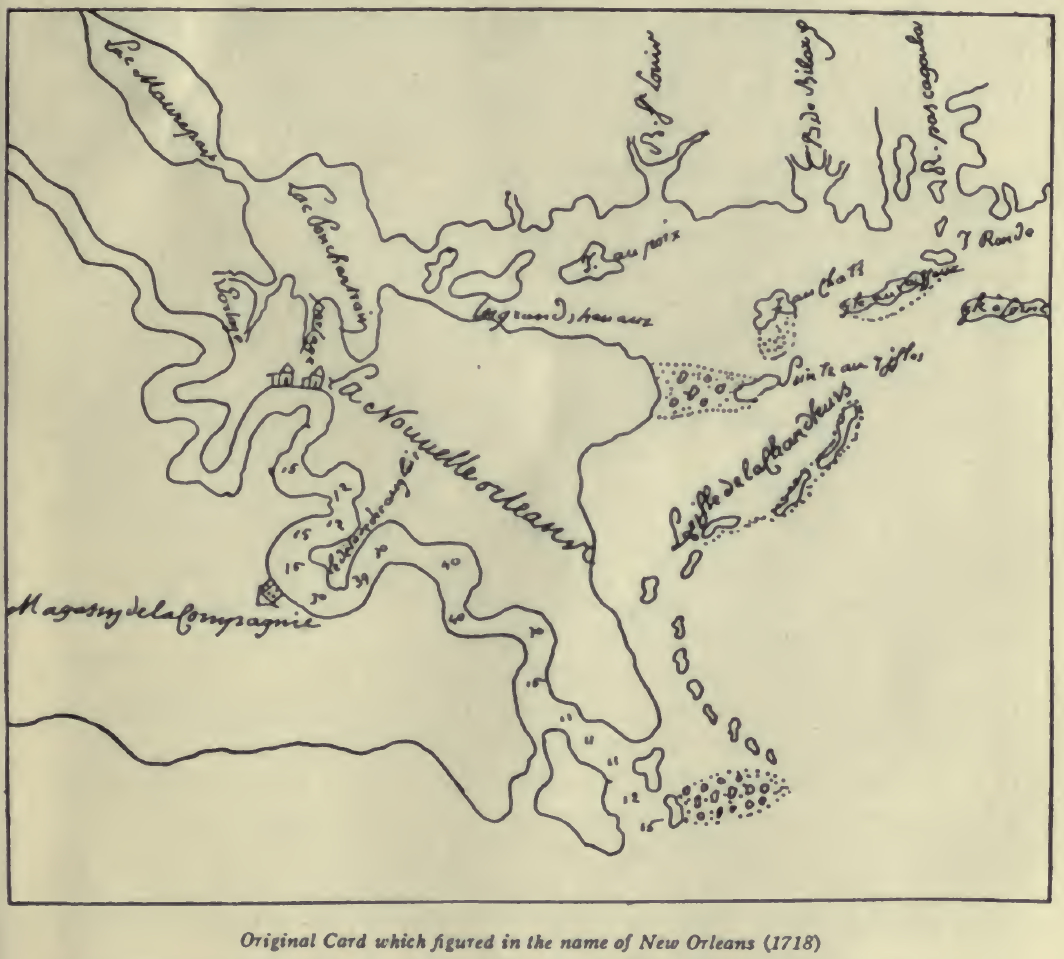

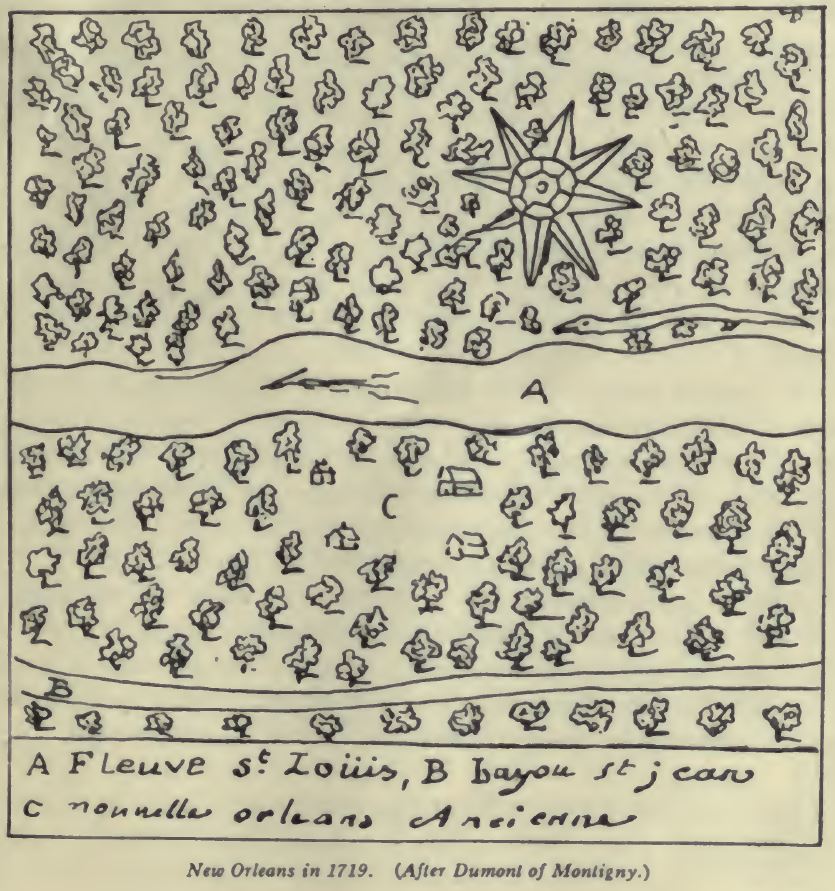

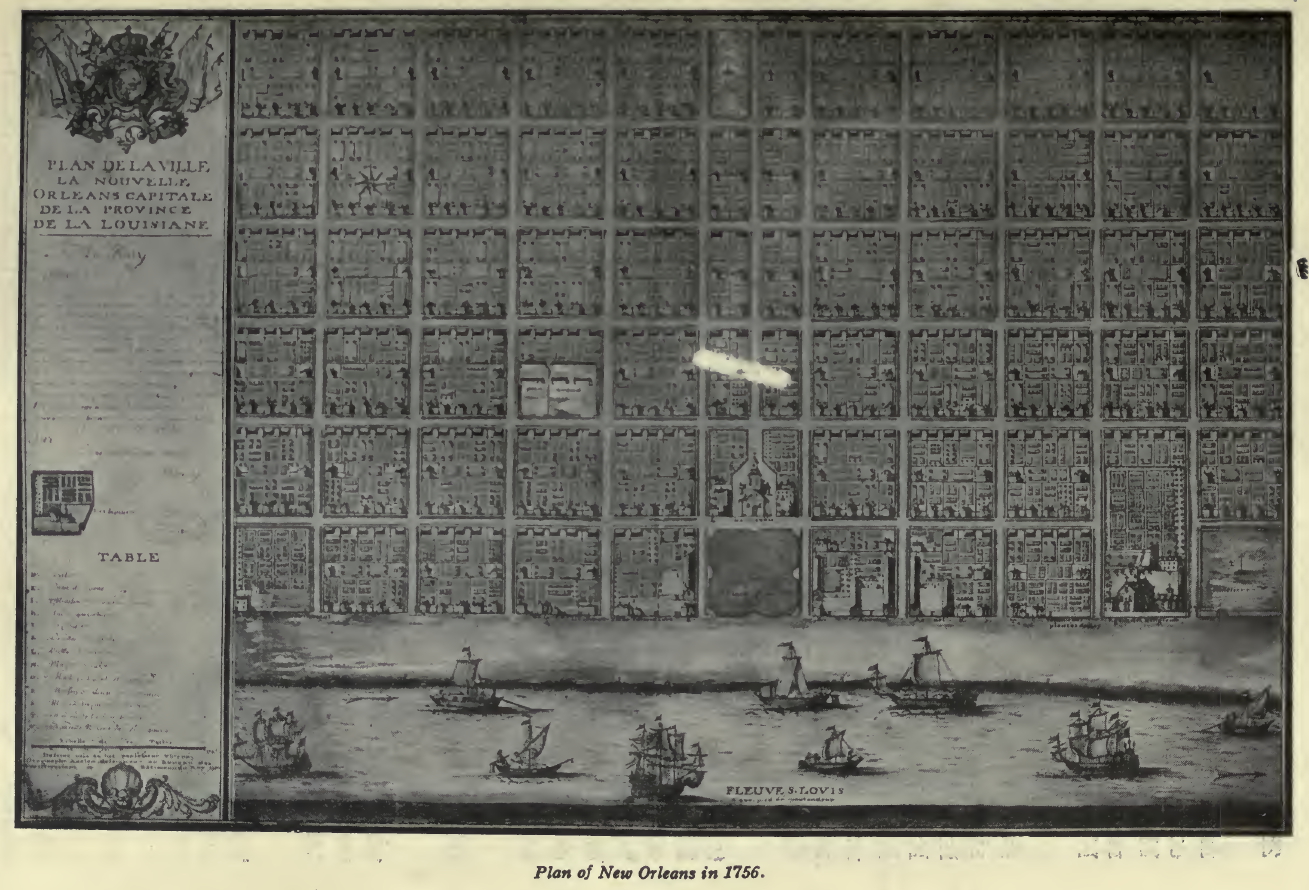

The National Library preserves a singular aquarelle purporting to picture New Orleans at the end of January, 1720; it was done on a corner of the map entitled “Carte nouvelle de la partie occidentale de la province de Louisiane,” according to “observations and discoveries made by the Sieur Bénard de La Harpe, Commandant on Red River,” by the “Sieur de Beauvilliers, gentleman serving the King and his engineer in Ordinary, of the Royal Academy of Sciences, at Paris, in November, 1720.” (Bibl. Nat., Cartes, Inv. Gen. 1073.) This sketch is reproduced at the head of the present chapter.

La Harpe was an excellent observer, M. de Beauvilliers an able geographer, and their map seems remarkably accurate, for the period. If their view of New Orleanss contains many errors, it is because they represented not reality but a mere project. The drawing shows the Mississippi Crescent, beyond which Lake Pontchartrain is seen in the distance, as if the canal planned by La Harpe to connect the river with the lake had existed already. Later in the year, on the 20th of December, La Harpe wrote: “Communications may be made between the Mississippi and Lake Pontchartrain; there will be only half a league of cutting to do.” Bienville appears to have been a partisan of this, for a while, but doubtless only to conciliate the inhabitants of Biloxi.

This view, whose perspective placed the lake very near the river, could not but encourage the Company to continue work at Biloxi which La Harpe strongly championed. The fact that three large stores or barracks, which existed then only in the imagination of Pénicaut and of La Harpe, were represented as actually completed, served as further inducement for the Directors to neglect New Orleans.

In April, the Colonial Board, seeing no necessity for the maintenance of a major and a captain at that almost deserted post, withdrew the appointments of d’Avril and of Valterre, replacing them by M. de Noyan, a mere lieutenant. Somewhat later, M. de Riche-bourg was nevertheless named as Major, but refused to serve under the orders of Pailloux who, according to his adversary La Mothe-Cadillac, was “a choleric ex-sergeant addicted to maltreating his men.” Richebourg also was reputed as violent; on the 8th of April, 1719, the Company had ordered that “having insulted Mme. Hubert, he must give suitable satisfaction.” Richebourg had served two years as volunteer in the King’s Household, four years in the Limoges Regiment, eleven years as captain, then as major, in the Chatillon dragons, and had gone to Louisiana in 1712.

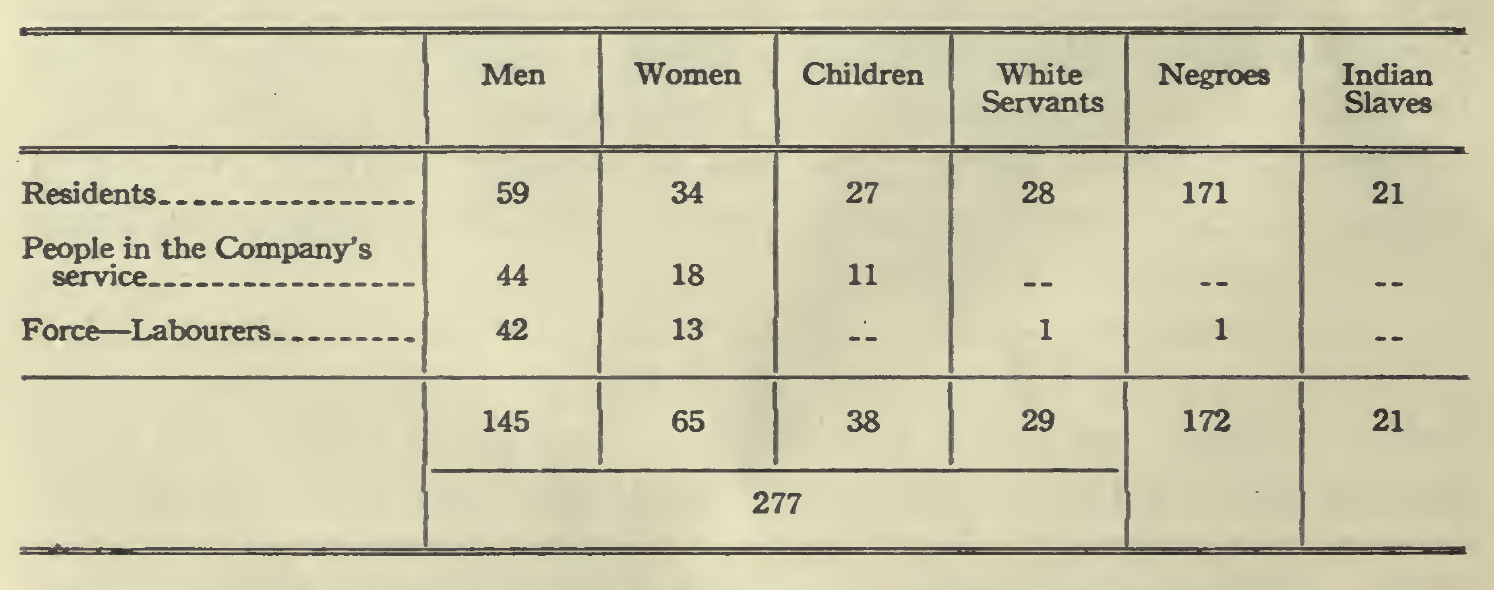

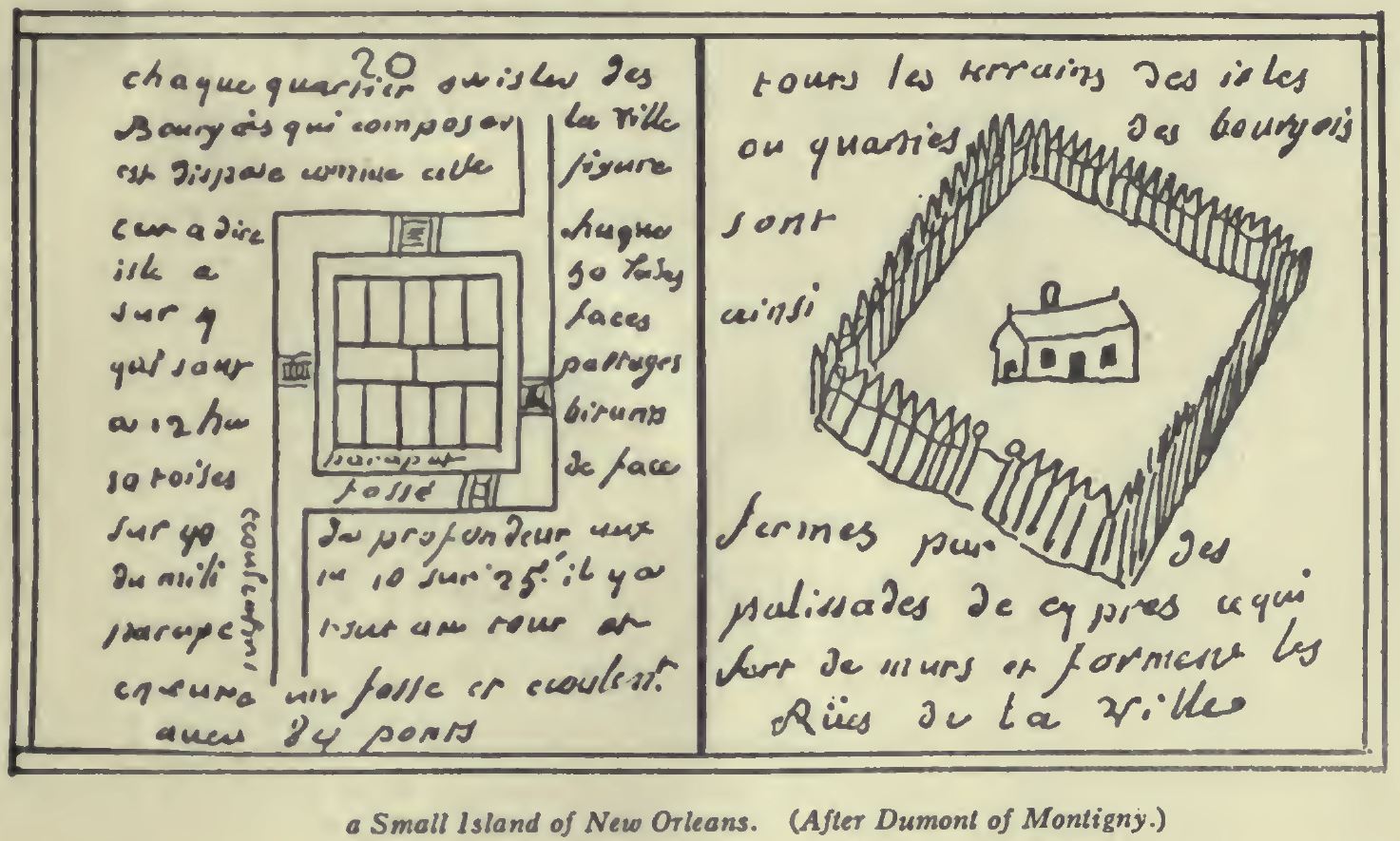

An Etat de la Louisiane for June, 1720 says: “The burg of New Orleans is situated thirty leagues above the mouth of the Mississippi, on the eastern side. There are stores for the Company, a hospital, lodgings for the governor and the Director. About fifty soldiers, seventy clerks, hired men and convicts drawing wages and rations from the Company. Two hundred and fifty concession-holders, including their people, are waiting for flat-boats to take them up to their concessions.”

“There are, on that side, forty plantations begun by invalids who, to judge by appearances, will not make good. Of these forty concessions, only two will be able to produce crops this year: one belongs to the Sieur Lery (the surname of Joseph Chauvin) who, in March, had already sowed two casks of rice; the other, to the Sieurs Massy and Guenot, who have sowed as much. These forty plantations have among them about thirty head of horned cattle and eighty slaves, savages as well as blacks.

“M. de Bienville, commander of Louisiana, also has a plantation there (Bel Air) in which he has put twenty slaves, blacks and savages, and six head of horned cattle. He has sowed half a cask of rice. The river, which overflows almost every year, is a cause of inconvenience and damage to many houses built too close to the waters. The burg should naturally be placed where the Sieur Hubert chose his plantation. The ground is always dry there, and the public would be all the better off, since it is accessible from both sides, the Mississippi and the Bayou.”

Fearing lest caprice might prompt a few colonists in distress to settle near New Orleans, the Councillors passed a stringent measure: “The hundred and fifty persons who had been sent to New Orleans are now all at Biloxi,” Le Gac writes. “It was considered more appropriate to provide for them here than in New Orleans. They could not be conveyed by river, because the flatboats were all away and not expected back soon.” And yet, game was far more abundant on the shores of the Mississippi than near Biloxi.

Save for a few pirogues and flat-boats, the entire fleet kept by the Company at New Orleans was limited, even at the close of 1720, to a “sunken brigantine.” “But,” adds Le Gac, “she could be raised, for there are no worms in the river.” Here was an additional point in favour of New Orleans, whereas at Biloxi a ship’s hull rapidly became a sieve. To obviate the shortness of bottoms, and to avoid a fresh return of colonists, Bienville caused du Tisné to pass through the mouths of the Mississippi, in October, 1720, with a flotilla of seven flat-boats.

Pénicaut has little to say about New Orleans during the year 1720; he rests content with observing: “They worked the rest of the year, and made considerable progress.” Valette de Laudun, who wrote only from hearsay, he himself having never gone beyond Biloxi, declares in his Journal d’un voyage fait a la Louisiane en 1720: “New Orleans is the first and most important of the posts we have here.” Nevertheless, the site of the capital must have borne closer affinities to a virgin forest than to a town, since in March, 1721 Pauget the engineer complained that he “could not make the alignments” because there were too many bushes and cane-brakes.

Work on the dikes continued, meanwhile. Pellerin wrote in 1720 (probably on the 1st of August): “The Mississippi, overflowing more or less for six months of the year, renders New Orleans unpleasant as a place of sojourn. But at present, a great many slaves or negroes from Guinea are labouring to make it habitable. This may be effected by a sound dike on the river-bank; or by a causeway three or four toises from the edge and running back a quarter of a league where the land rises above inundation; or else by digging a small bayou to act as drain in winter. Pirogues from the Mississippi on the one hand, and from Lake Pontchartrain on the other, could then anchor beside the town. * * * Ships drawing not more than thirteen or fourteen feet can come up to New Orleans.”

Having settled in Natchez, Pellerin was a warm partisan of that post, and rejoiced because Hubert had “filled the Natchez stores, which caused much discontent at New Orleans, as if dwellers in Natchez were less sons of the Colony than those in New Orleans. By so doing, M. the Commissary will have Natchez established within two years, whereas down the river it cannot be done in six. Yet the good things brought by boat are consumed down the river, and we don’t taste them except when they are no longer wanted there, or when travellers bring them to us” (Arsenal, Mss. 4497, fol. 54.)

The year 1720 brings to a close the first period of the foundation of New Orleans. The town’s history from 1718 to 1721 might almost be expressed in a few words, saying that, helped by the choice of a good site and by Bienville’s tenacity, the capital of Louisiana concentrated its efforts on remaining rooted where it was, otherwise passively biding the time when its very enemies should understand the brilliancy of the future awaiting it. During three years, adversaries succeeded in completely checking the development of New Orleans but failed in their endeavour to transfer it to the banks of Lake Pontchartrain. Bienville’s name will always remain deservedly associated with the creation of the great seaport of the Mississippi, which he founded in spite of everybody.

If New Orleans owes its existence to Bienville, the first colonists have to thank him for preserving their lives. But for the marvellous ability which the “Father of Louisiana” showed in winning the friendship of Indian tribes, the French who came as pioneers to settle along the Mississippi would all have been massacred. But Indians adored Bienville while fearing him, because they knew him to be always just, though often stern.

Bienville’s character was unquestionably authoritative; but for thirty-five years he displayed in Louisiana all the energy required for the government of a new colony ceaselessly torn by rivalries of men or of interests.

CHAPTER IV.