The Century Magazine

“Creole Slave Songs”

————

CREOLE SLAVE SONGS.

I.

THE QUADROONS.

THE patois in which these songs are found is common, with broad local variations, wherever the black man and the French language are met in the mainland or island regions that border the Gulf and the Caribbean Sea. It approaches probably nearer to good French in Louisiana than anywhere in the Antilles. Yet it is not merely bad or broken French; it is the natural result from the effort of a savage people to take up the language of an old and highly refined civilization, and is much more than a jargon. The humble condition and great numbers of the slave-caste promoted this evolution of an African-Creole dialect. The facile character of the French master-caste, made more so by the languorous climate of the Gulf, easily tolerated and often condescended to use the new tongue. It chimed well with the fierce notions of caste to have one language for the master and another for the slave, and at the same time it was convenient that the servile speech should belong to and draw its existence chiefly from the master’s. Its growth entirely by ear where there were so many more African ears than French tongues, and when those tongues had so many Gallic archaisms which they were glad to give away and get rid of, resulted in a broad grotesqueness all its own.

We had better not go aside to study it here. Books have been written on the subject. They may be thin, but they stand for years of labor. A Creole lady writes me almost as I write this, “It takes a whole life to speak such a language in form.” Mr. Thomas of Trinidad has given a complete grammar of it as spoken there. M. Marbot has versified some fifty of La Fontaine’s fables in the tongue. Pere Gaux has made a catechism in, and M. Turiault a complete grammatical work on, the Martinique variety. Dr. Armand Mercier, a Louisiana Creole, and Professor James A. Harrison, an Anglo-Louisianian, have written valuable papers on the dialect as spoken in the Mississippi delta. Mr. John Bigelow has done the same for the tongue as heard in Hayti. It is an amusing study. Certain tribes of Africa had no knowledge of the v and z sounds. The sprightly Franc-Congos, for all their chatter, could hardly master even this African-Creole dialect so as to make their wants intelligible. The Louisiana negro’s r’s were ever being lost or mislaid. He changed dormir to dromi’. His master’s children called the little fiddler-crab Tourlourou; he simplified the articulations to Troolooloo. Wherever the r added to a syllable’s quantity, he either shifted it or dropped it overboard. Po’te ca? Non! not if he could avoid it. It was the same with many other sounds. For example, final le; a thing so needless — he couldn’t be burdened with it; li pas capab’! He found himself profitably understood when he called his master aimab’ et nob’, and thought it not well to be trop sensib’ about a trifling l or two. The French u was vinegar to his teeth. He substituted i or ei before a consonant and oo before a vowel, or dropped it altogether; for une, he said eine; for puis, p’is; absolument he made assoliment; tu was nearly always to; a mulâtresse was a milatraisse. In the West Indies he changed s into ch or tch, making songer chonge, and suite tchooite; while in Louisiana he reversed the process and turned ch into c — c’erc’e for cherchez or chercher.

He misconstrued the liaisons of correct French, and omitted limiting adjectives where he conveniently could, or retained only their final sound carried over and prefixed to the noun: nhomme — zanimaux — zherbes — zaffaires. He made odd substitutions of one word for another. For the verb to go he oftener than otherwise used a word that better signified his slavish pretense of alacrity, the verb to run: mo courri — mo always, never je, — mo courri, to courri, li courri: always seizing whatever form of a verb was handiest and holding to it without change; no courri, vo courri, yé courri Sometimes the plural was no zôtt — we others — courri, co zôtt courri, yé zôtt courri; no zôtt courri dans bois — we are going to the woods. His auxiliary verb in im perfect and pluperfect tenses was not to have, but to be in the past participial form été, but shortened one syllable. to I have gone, thou hadst gone: mo ’té courri, to ’té courri.

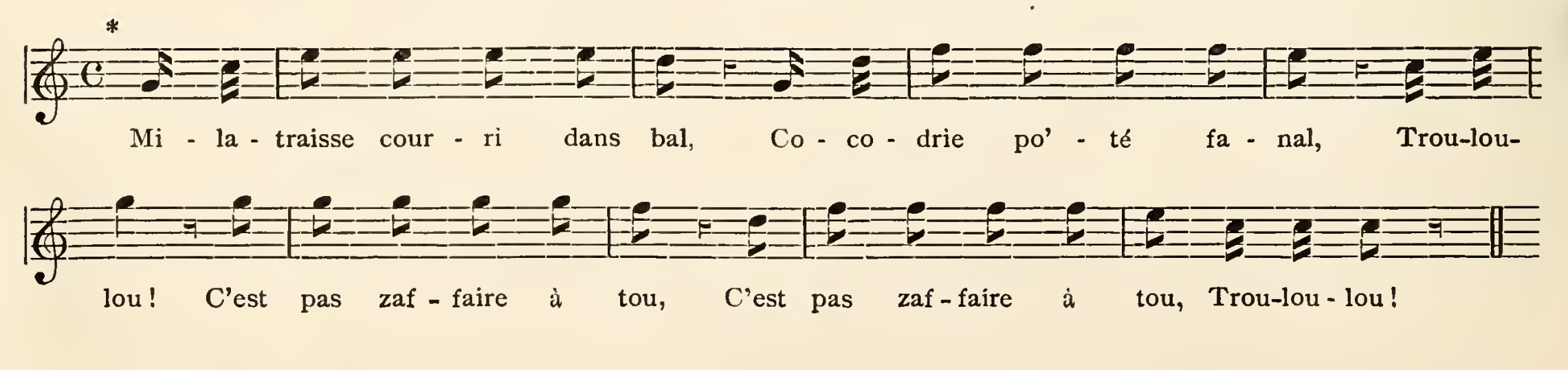

There is an affluence of bitter meaning hidden under these apparently nonsensical lines.*

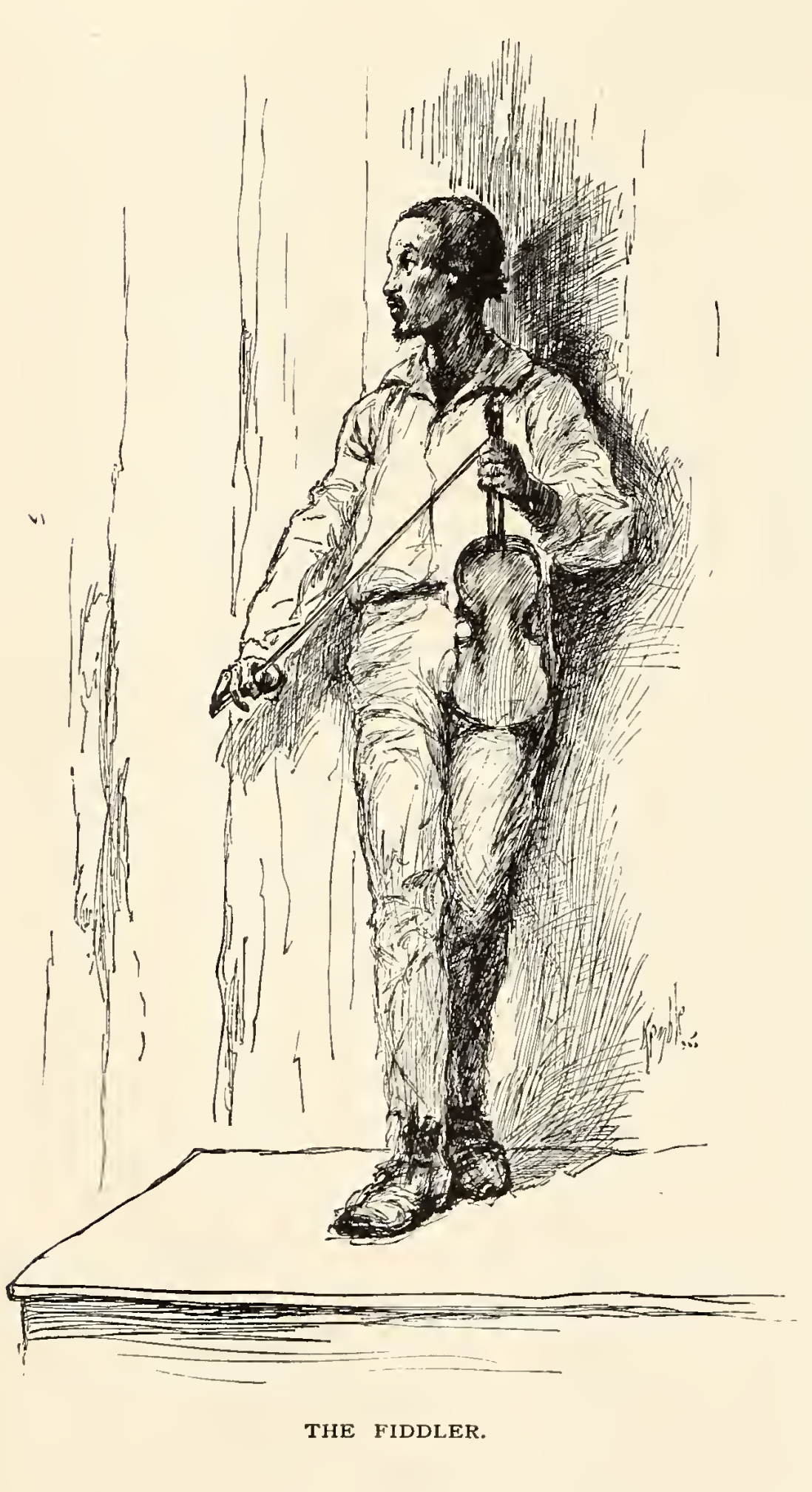

It mocks the helpless lot of three types of human life in old Louisiana whose fate was truly deplorable. Milatraisse was, in Creole song, the generic term for all that class, fa mous wherever New Orleans was famous in those days when all foot-passengers by night picked their way through the mud by the rays of a hand-lantern — the freed or free-born quadroon or mulatto woman. Cocodrie (Spanish, cocodrilla, the crocodile or alligator) was the nickname for the unmixed black man; while trouloulou was applied to the free male quadroon, who could find admittance to the quadroon balls only in the capacity, in those days distinctly menial, of musician — fiddler. Now sing it!

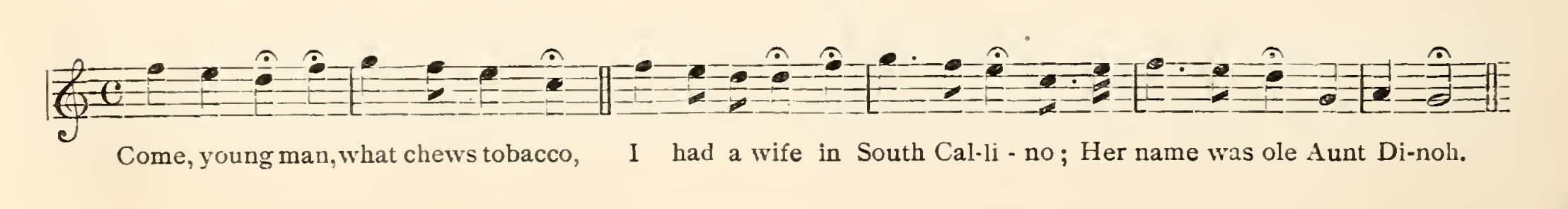

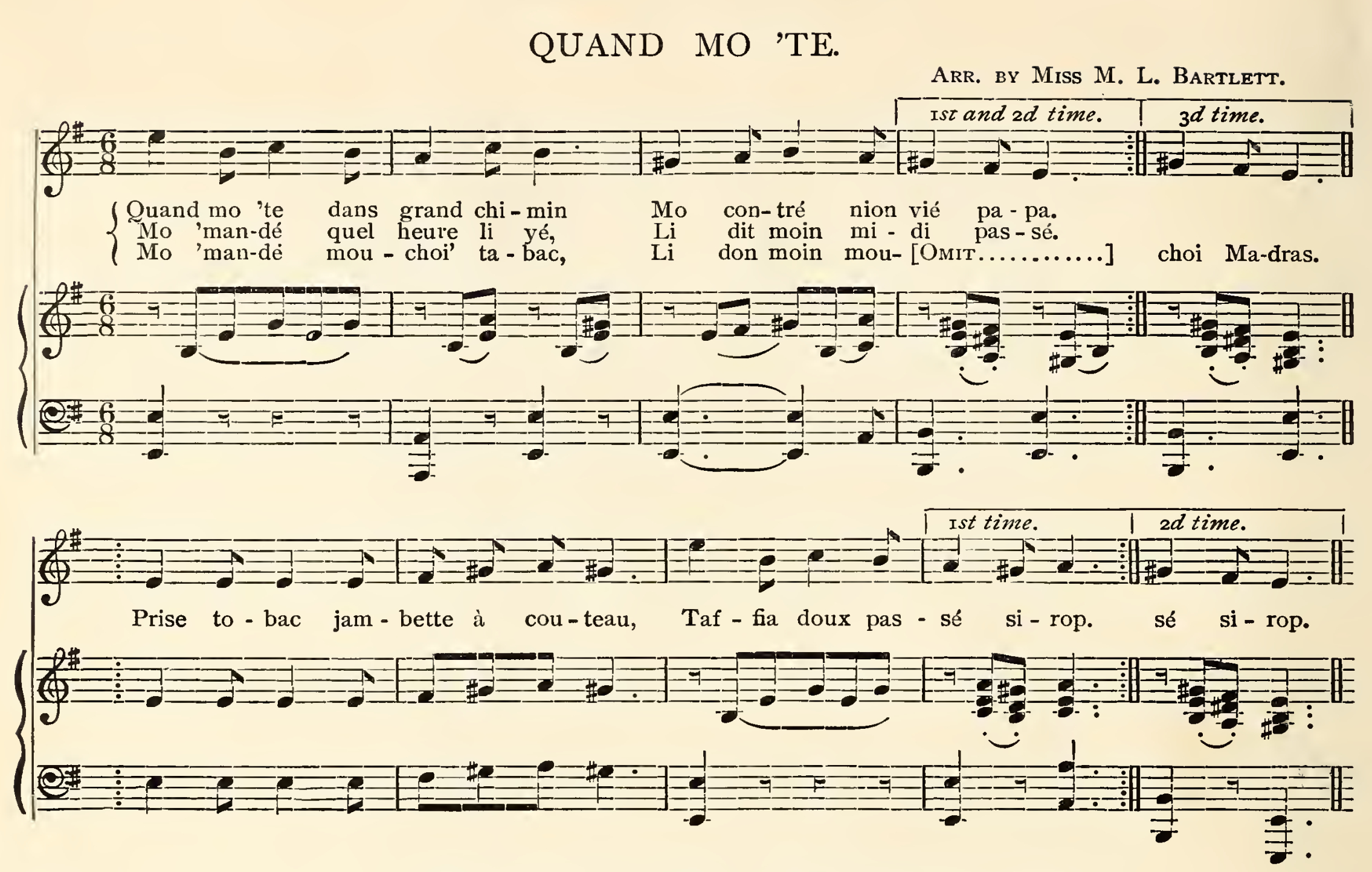

It was much to him; but it might as well have been little. What could he do? As they say, “Ravette zamein tini raison divant poule” ("Cockroach can never justify himself to the hungry chicken"). He could only let his black half-brother celebrate on Congo Plains the mingled humor and outrage of it in satirical songs of double meaning. They readily passed unchallenged among the numerous nonsense rhymes — that often rhymed lamely or not at all — which beguiled the hours afield or the moonlight gatherings in the “quarters,” as well as served to fit the wild chants of some of their dances. Here is one whose characteristics tempt us to suppose it a calinda, and whose humor consists only in a childish play on words. (Quand Mo ’Te, page 824.)

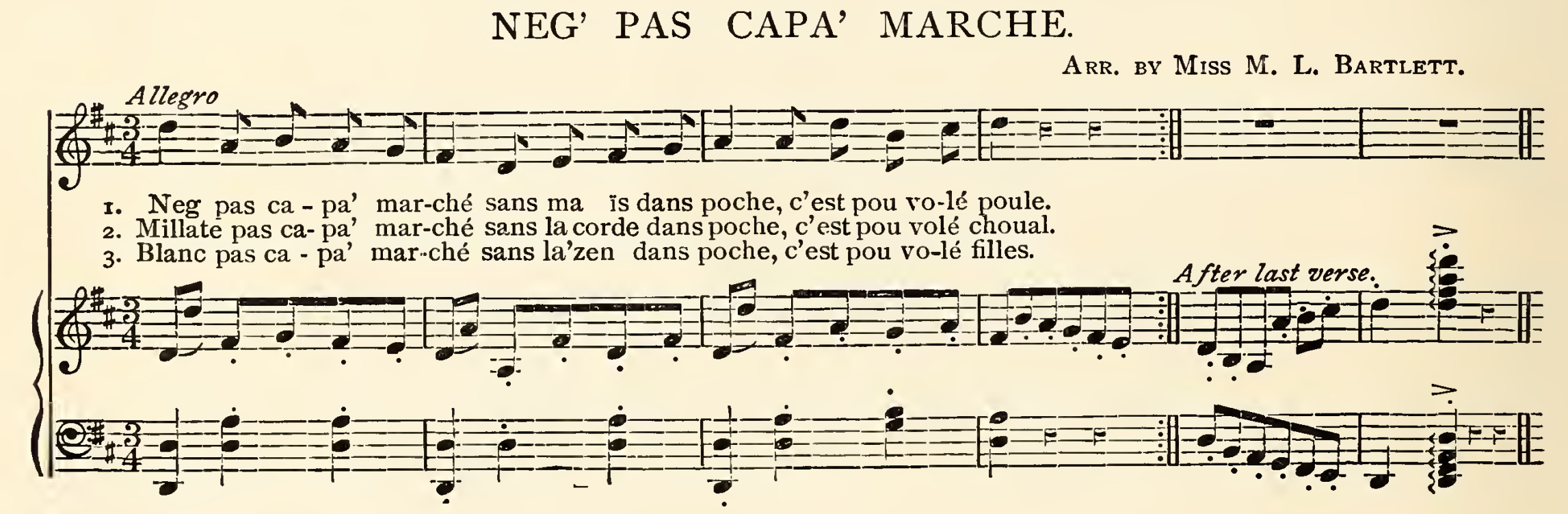

There is another nonsense song that may or may not have been a dance. Its movement has the true wriggle. The dances were many; there were some popular in the West Indies that seem to have remained compara- tively unknown in Louisiana: the belair, bèlè, or béla; the cosaque; the biguine. The guiouba was probably the famed juba of Georgia and the Carolinas. (Neg’ pas Capa’ Marche, page 824.)

II.

THE LOVE-SONG.

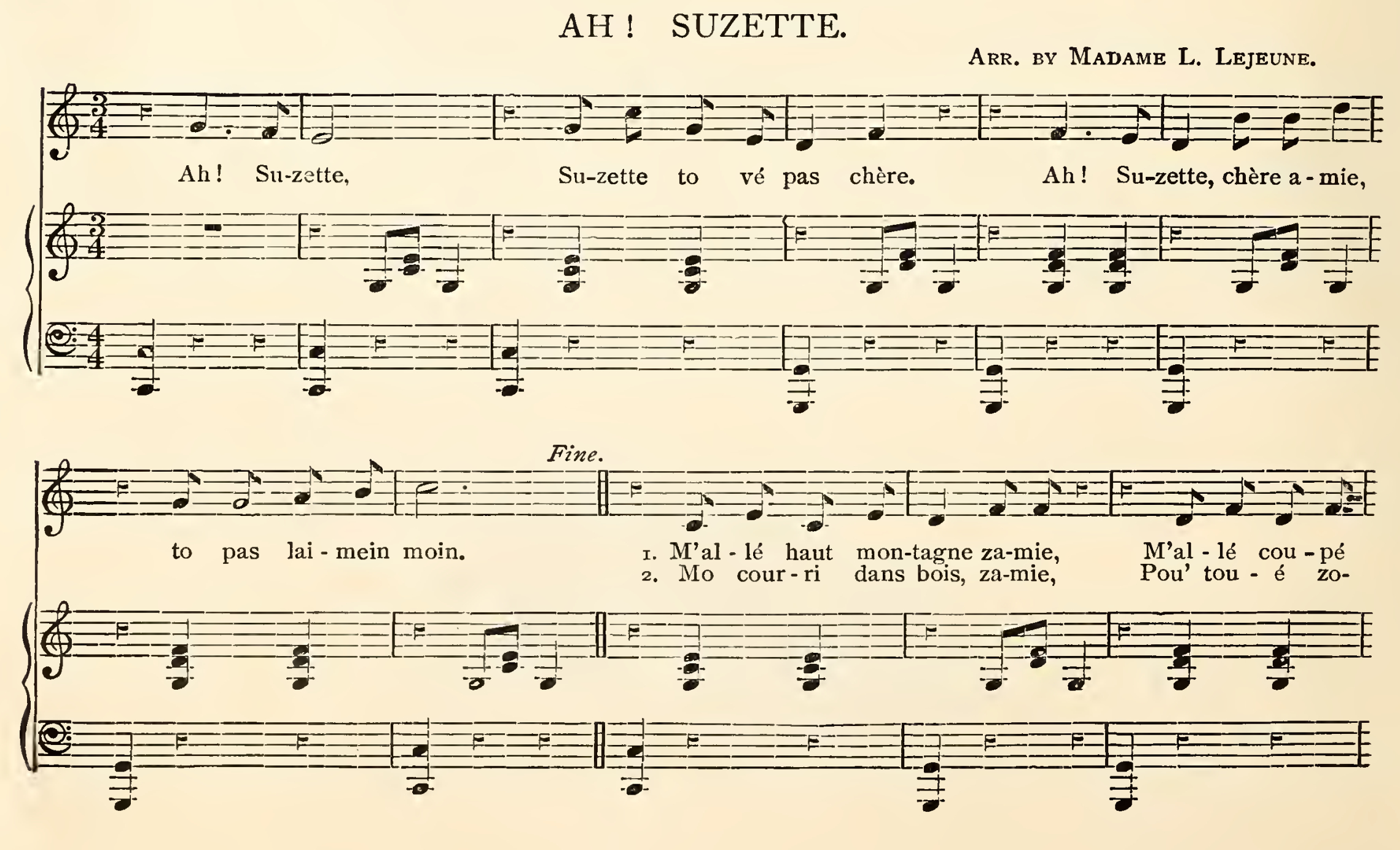

AMONG the songs which seem to have been sung for their own sake, and not for the dance, are certain sentimental ones of slow movement, tinged with that faint and gentle melancholy that every one of Southern experience has noticed in the glance of the African slave’s eye; a sentiment ready to be turned, at any instant that may demand the change, into a droll, self-abasing humor. They have thus a special charm that has kept for them a place even in the regard of the Creole of to-day. How many ten thousands of black or tawny nurse “mammies,” with heads wrapped in stiffly starched Madras kerchief turbans, and holding ’tit mait’e or ’tit maitresse to their bosoms, have made the infants’ lullabies these gently sad strains of disappointed love or regretted youth, will never be known. Now and then the song would find its way through some master’s growing child of musical ear, into the drawing-room; and it is from a Creole drawing-room in the Rue Esplanade that we draw the following, so familiar to all Creole ears and rendered with many variations of text and measure. (Ah Suzette, page 824.)

One may very safely suppose this song to have sprung from the poetic invention of some free black far away in the Gulf. A Louisiana slave would hardly have thought it possible to earn money for himself in the sugar-cane fields. The mention of mountains points back to St. Domingo.

It is strange to note in all this African-Creole lyric product how rarely its producers seem to have recognized the myriad charms of nature. The landscape, the seasons, the sun, moon, stars, the clouds, the storm, the peace that follows, the forest’s solemn depths, the vast prairie, birds, insects, the breeze, the flowers — they are passed in silence. Was it because of the soul-destroying weight of bondage? Did the slave feel so painfully that the beauties of the natural earth were not for him? Was it because the overseer’s eye was on him that his was not lifted upon them? It may have been — in part. But another truth goes with these. His songs were not often contemplative. They voiced not outward nature, but the inner emotions and passions of a nearly naked serpent-worshiper, and these looked not to the surrounding scene for sympathy; the surrounding scene belonged to his master. But love was his, and toil, and anger, and superstition, and malady. Sleep was his balm, food his reënforcement, the dance his pleasure, rum his longed-for nepenthe, and death the road back to Africa. These were his themes, and furnished the few scant figures of his verse.

The moment we meet the offspring of his contemplative thought, as we do in his apothegms and riddles, we find a change, and any or every object in sight, great or trivial, comely or homely, is wrought into the web of his traditional wit and wisdom. “Vo mié, savon, passé godron,” he says, to teach a lesson of gentle forbearance (“Soap is worth more than tar”). And then, to point the opposite truth, — “Pas marre so chien ave saucisse” (“Don’t chain your dog with links of sausage”). “Qui zamein ’tendé souris fé so nid dan zore ç’at?” (“Who ever heard of mouse making nest in cat’s ear?”) And so, too, when love was his theme, apart from the madness of the dance — when his note fell to soft cooings the verse became pastoral. So it was in the song last quoted. And so, too, in this very African bit, whose air I have not:

Shall we translate literally?

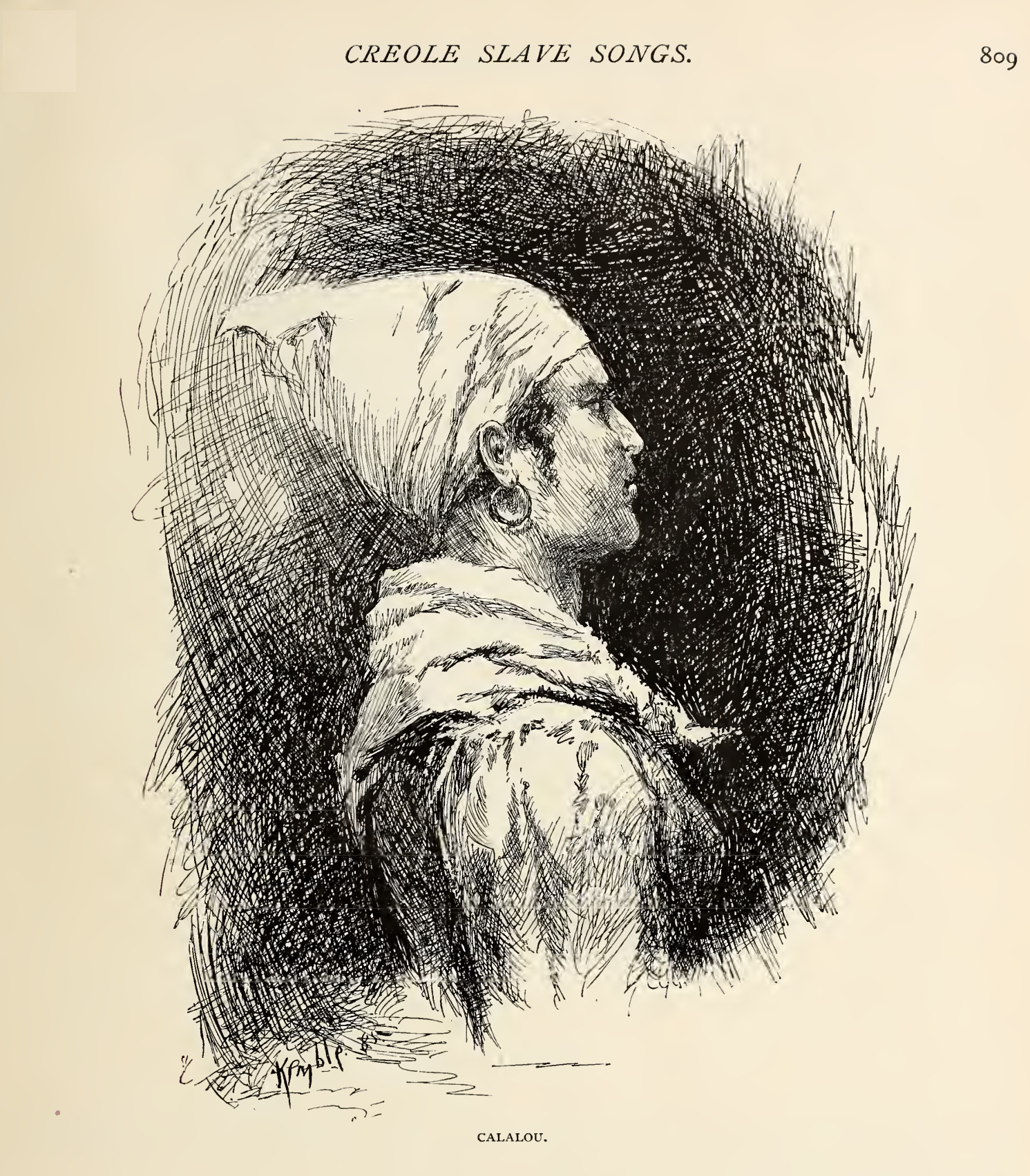

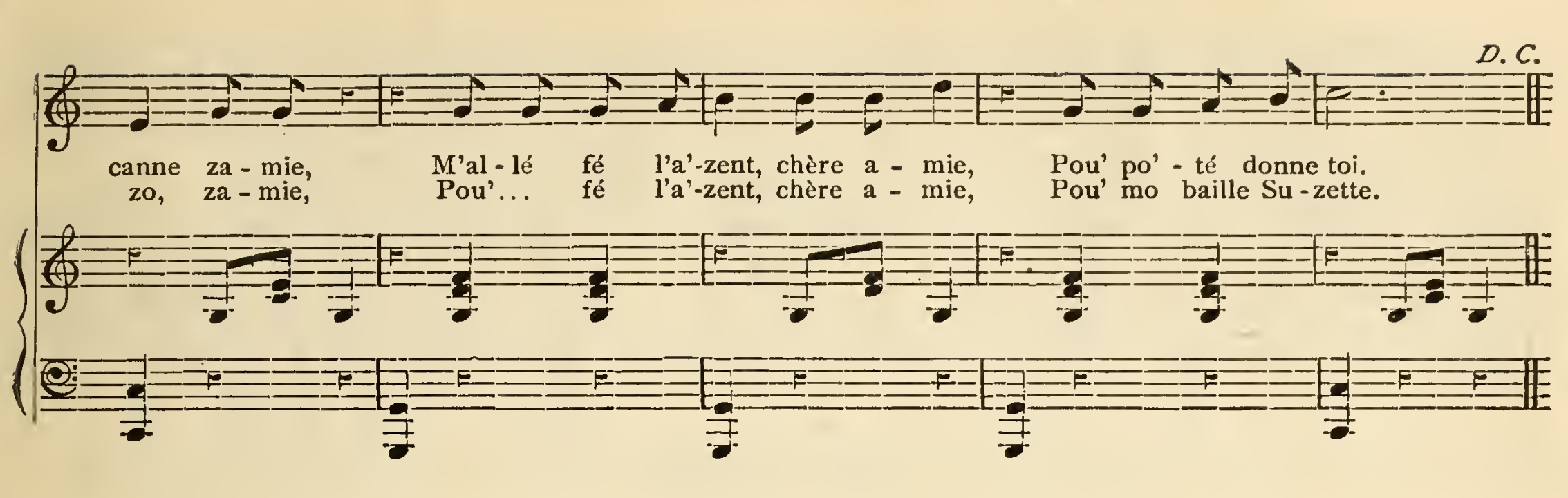

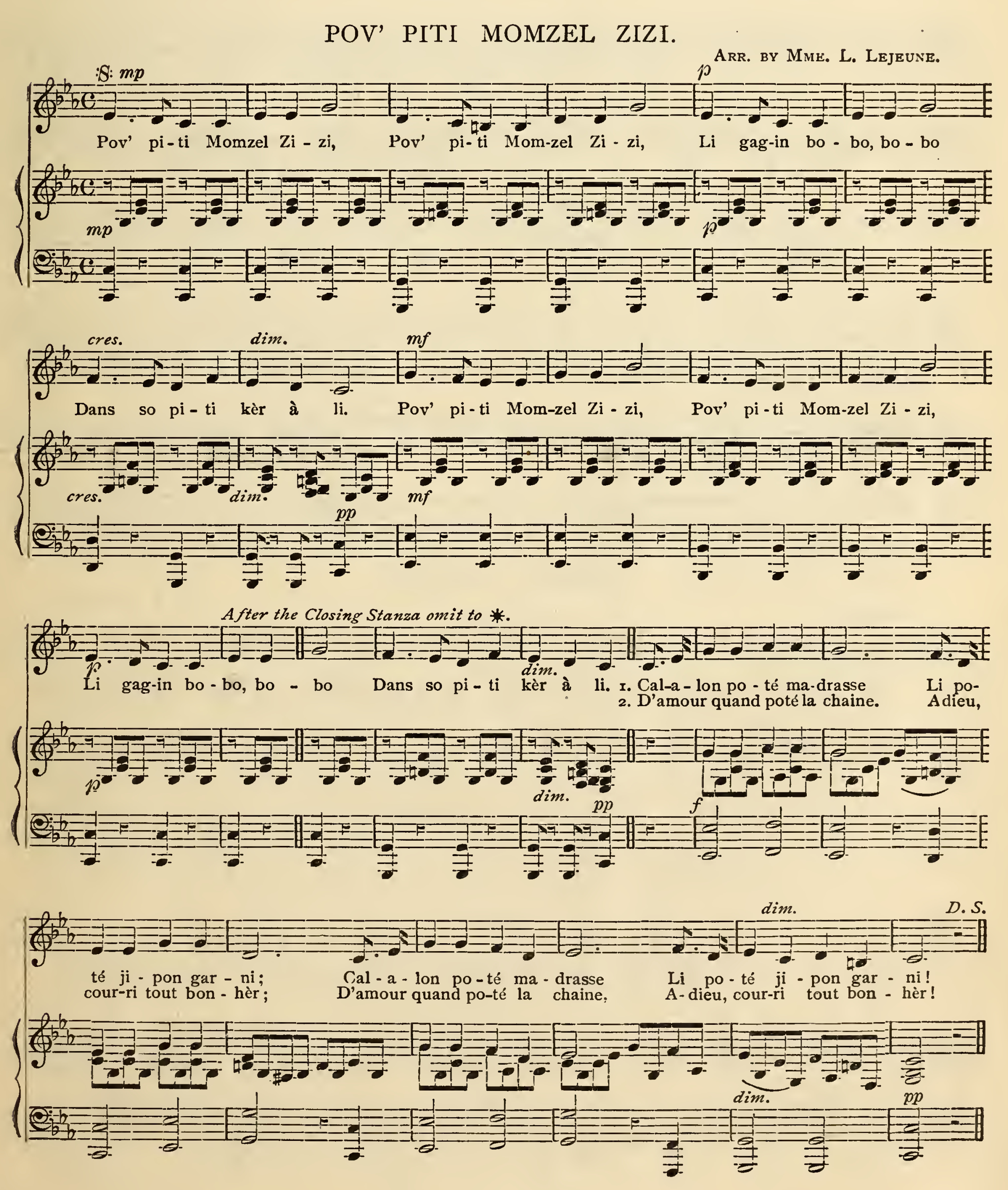

One of the best of these Creole love-songs — one that the famed Gottschalk, himself a New Orleans Creole of pure blood, made use of — is the tender lament of one who sees the girl of his heart’s choice the victim of chagrin in beholding a female rival wearing those vestments of extra quality that could only be the favors which both women had coveted from the hand of some one in the proud master-caste whence alone such favors could come. “Calalou,” says the song, “has an embroidered petticoat, and Lolotte, or Zizi,” as it is often sung, “has a — heartache.” Calalou, here, I take to be a derisive nickname. Originally it is the term for a West Indian dish, a noted ragout. It must be intended to apply here to the quadroon women who swarmed into New Orleans in 1809 as refugees from Cuba, Guadeloupe, and other islands where the war against Napoleon exposed them to Spanish and British aggression. It was with this great influx of persons neither savage nor enlightened, neither white nor black, neither slave nor truly free, that the famous quadroon caste arose and flourished. If Calalou, in the verse, was one of these quadroon fair ones, the song is its own explanation. (See Pov’ piti Momzel Zizi, page 825.)

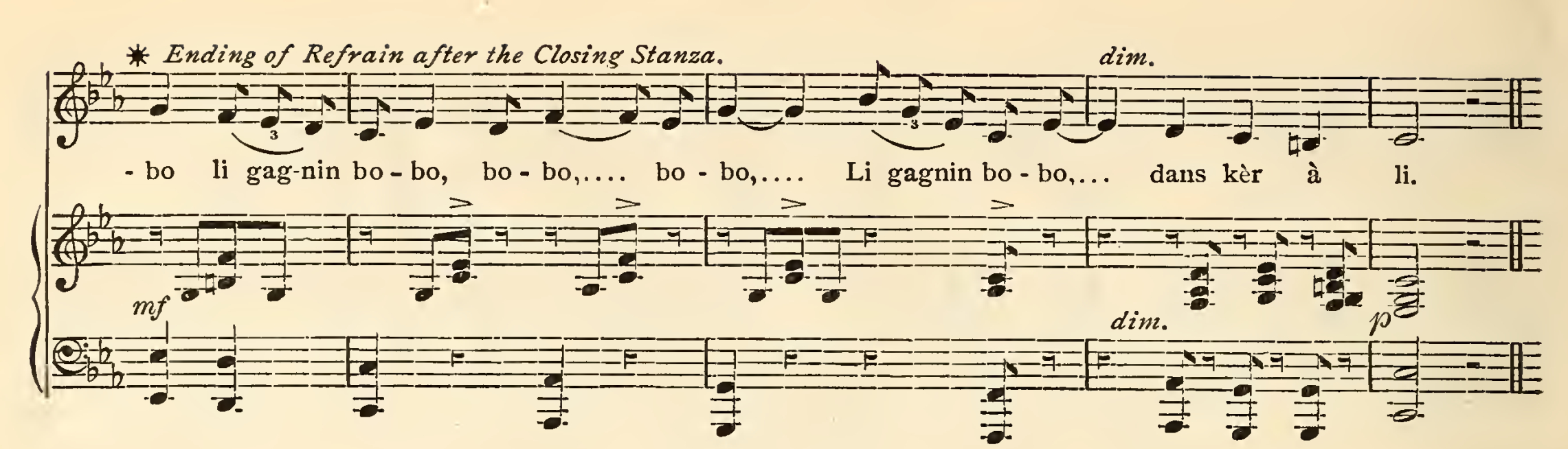

“Poor little Miss Zizi!” is what it means — “She has pain, pain in her little heart.” “À li” is simply the Creole possessive form; “corps à moin” would signify simply myself. Calalou is wearing a Madras turban; she has on an embroidered petticoat; [they tell their story and] Zizi has achings in her heart. And the second stanza moralizes: “When you wear the chain of love” — maybe we can make it rhyme:

Poor little Zizi! say we also. Triumphant Calalou! We see that even her sort of freedom had its tawdry victories at the expense of the slave. A poor freedom it was, indeed: To have f. m. c. or f. w. c. tacked in small letters upon one’s name perforce and by law, that all might know that the bearer was not a real freeman or freewoman, but only a free man (or woman) of color, — a title that could not be indicated by capital initials; to be the unlawful mates of luxurious bachelors, and take their pay in muslins, embroideries, prunella, and good living, taking with them the loathing of honest women and the salacious derision of the blackamoor; to be the sister, mother, father, or brother of Calalou; to fall heir to property by sufferance, not by law; to be taxed for public education and not allowed to give that education to one’s own children; to be shut out of all occupations that the master class could reconcile with the vague title of gentleman; to live in the knowledge that the law pronounced “death or imprisonment at hard labor for life” against whoever should be guilty of “writing, printing, publishing, or distributing anything having a tendency to create discontent among the free colored population”: that it threatened death against whosoever should utter such things in private conversation; and that it decreed expulsion from the State to Calalou and all her kin of any age or condition if only they had come in across its bounds since 1807. In the enjoyment of such ghastly freedom as this the flesh-pots of Egypt sometimes made the mouth water and provoked the tongue to sing its regrets for a past that seemed better than the present. (See Bon D’je, page 826.)

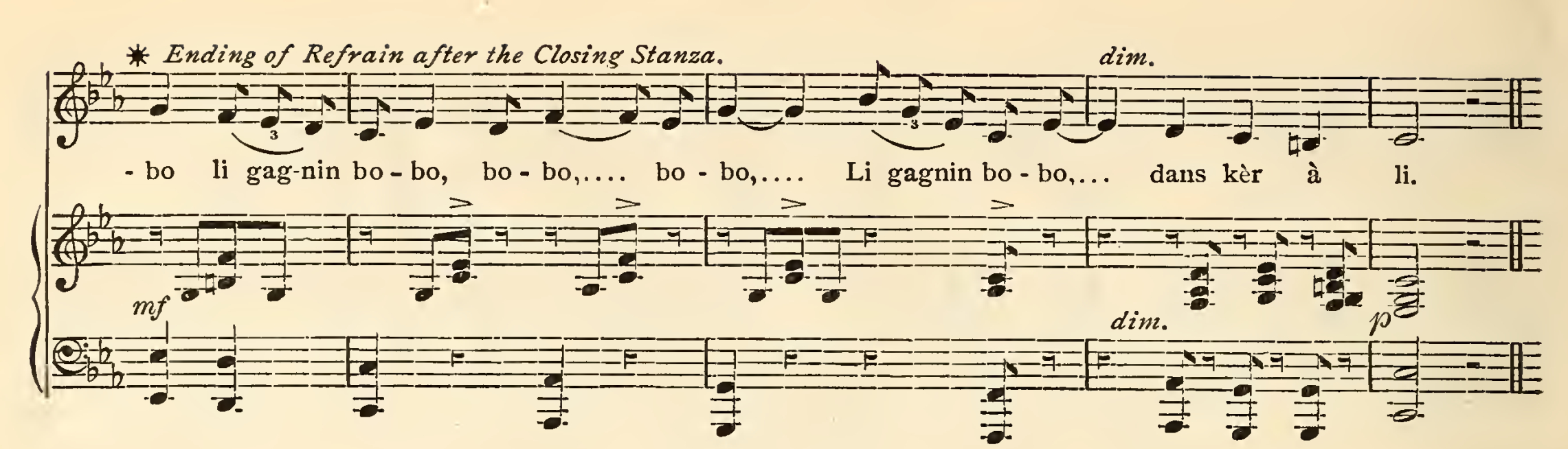

Word for word we should have to render it,—“In times when I was young I never pondered— indulged in reverie, took on care,” an archaic French word, zongler, still in use among the Acadians also in Louisiana; “mo zamein zonglé, bon D’jé”— “good Lord!” “Açtair” is “à cette heure”— “at this hour,” that is, “now— these days.” “These days I am getting old— I am pondering, good Lord!” etc. Some time in the future, it may be, some Creole will give us translations of these things, worthy to be called so. Meantime suffer this :

III.

THE LAY AND THE DIRGE.

THERE were other strains of misery, the cry or the vagabond laugh and song of the friendless orphan for whom no asylum door would open, but who found harbor and food in the fields and wildwood and the forbidden places of the wicked town. When that Creole whom we hope for does come with his good translations, correcting the hundred and one errors that may be in these pages, we must ask him if he knows the air to this:

Here was companionship with nature — the companionship of the vagabond. We need not doubt that these little orphan vagrants could have sung for us the song, from which in an earlier article we have already quoted a line or two, of Cayetano’s circus, probably the most welcome intruder that ever shared with the man Friday and his son g-dancing fellows and sweethearts the green, tough sod of Congo Square.

Should the Louisiana Creole negro undertake to render his song to us in English, it would not be exactly the African-English of any other State in the Union. Much less would it resemble the gross dialects of the English-torturing negroes of Jamaica, or Bar-badoes, or the Sea Islands of Carolina. If we may venture —

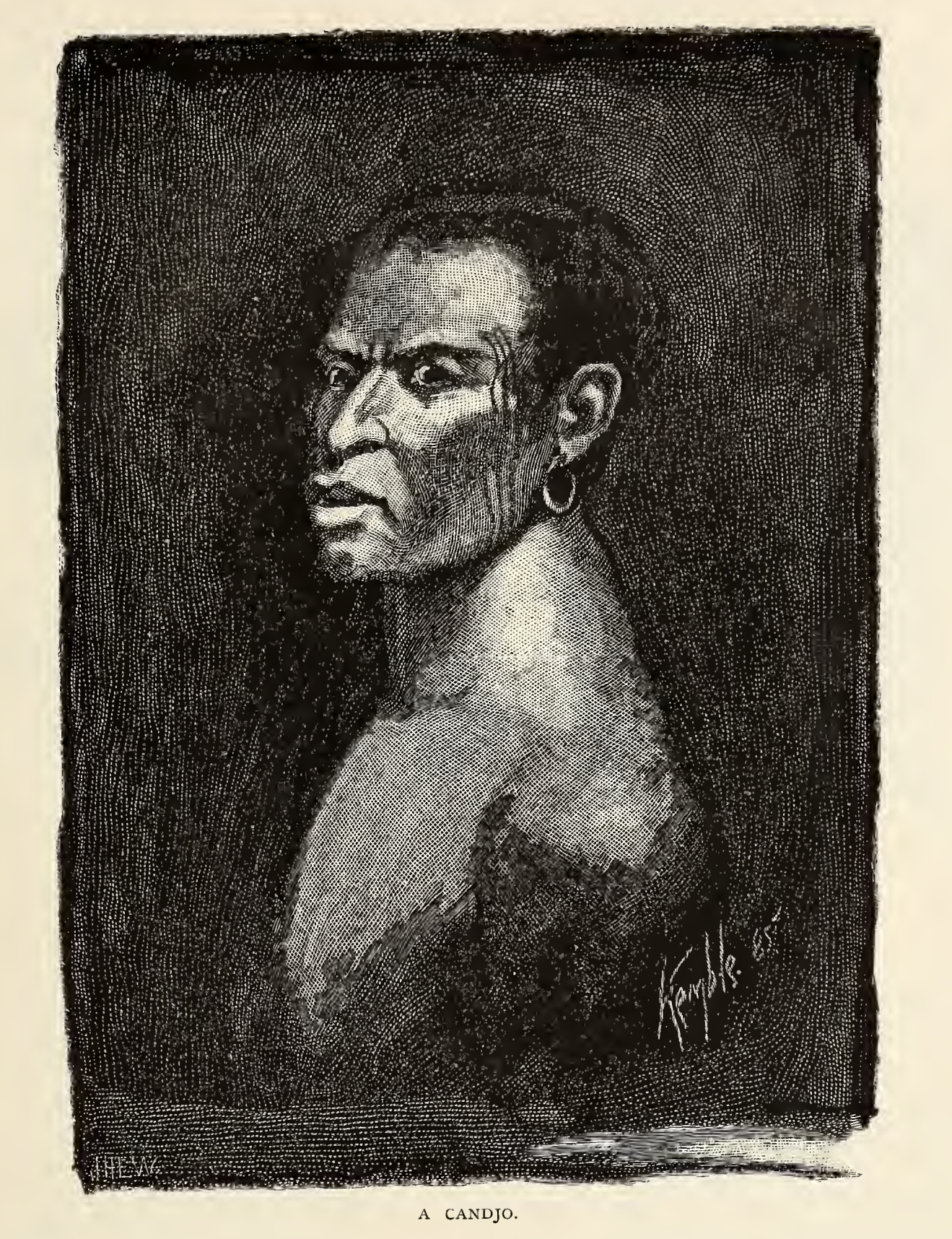

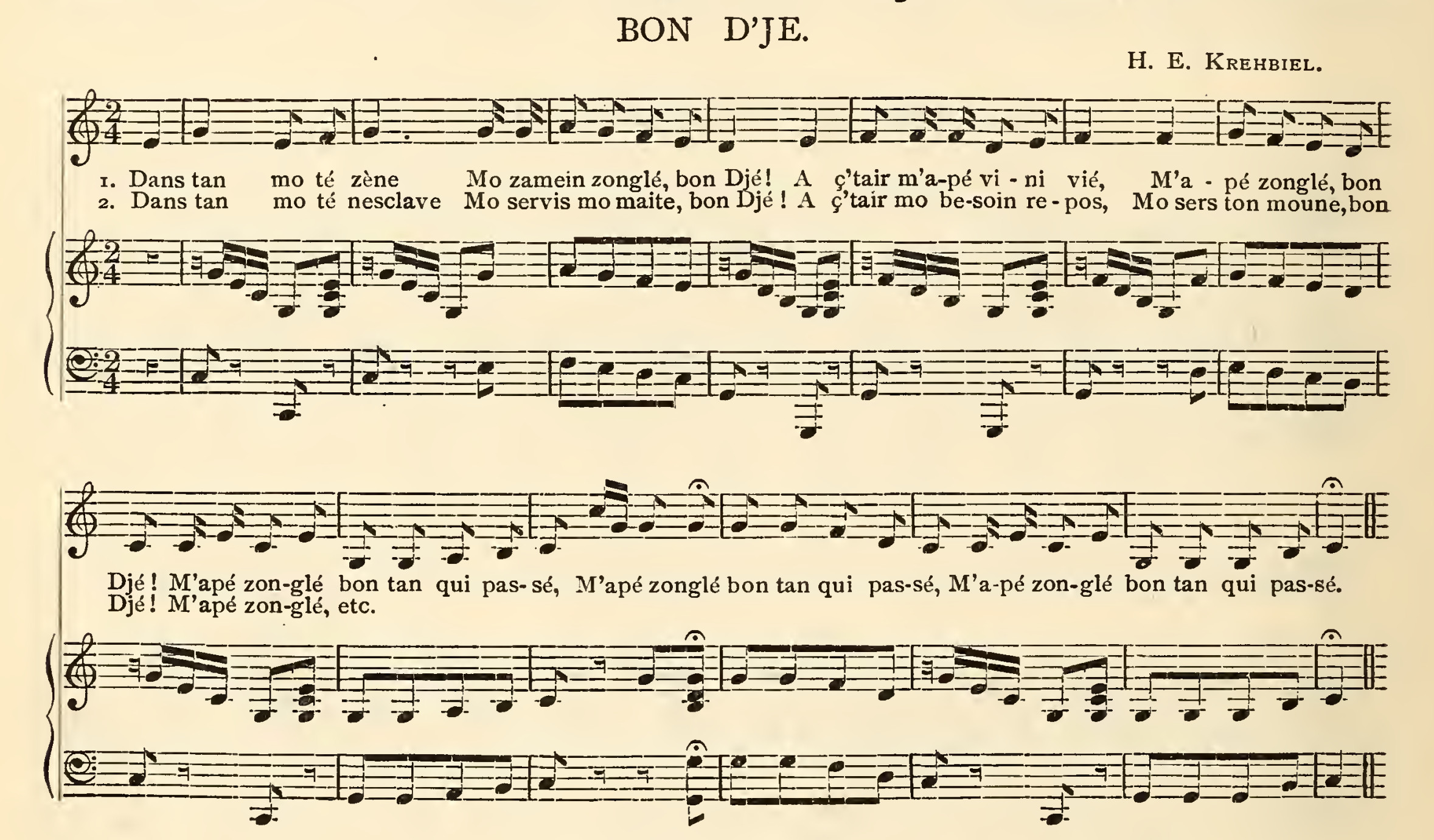

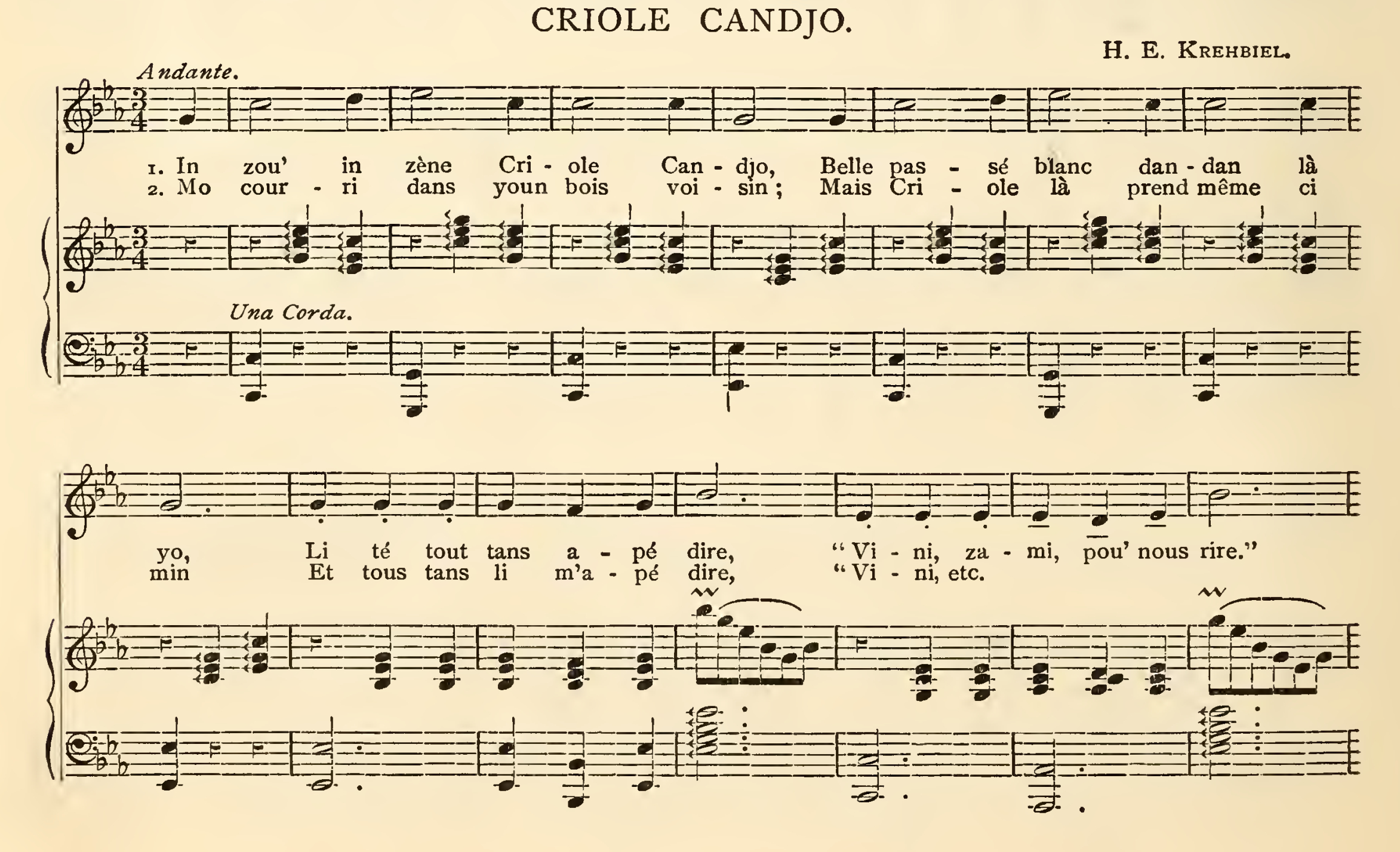

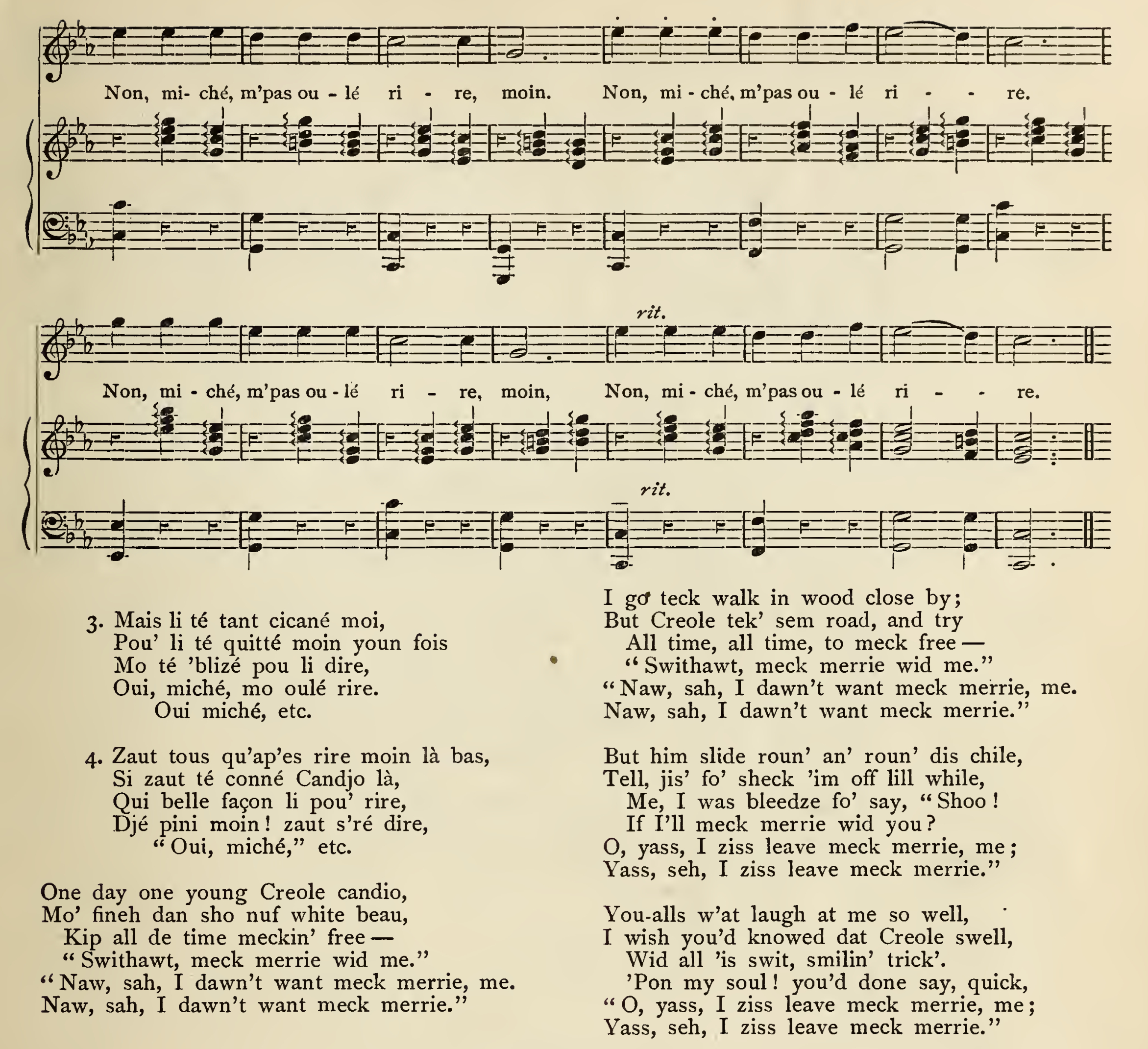

A remarkable peculiarity of these African Creole songs of every sort is that almost without exception they appear to have originated in the masculine mind, and to be the expression of the masculine heart. Untrained as birds, their males made the songs. We come now, however, to the only exception I have any knowledge of, a song expressive of feminine sentiment, the capitulation of some belle Layotte to the tender enticement of a Creole-born chief or candjo. The pleading tone of the singer’s defense against those who laugh at her pretty chagrin is — it seems to me —touching. (See Criole Candjo, page 826.)

But we began this chapter in order to speak of songs that bear more distinctly than anything yet quoted the features of the true lay or historical narrative song, commemorating pointedly and in detail some important episode in the history of the community.

It is interesting to contrast the solemnity with which these events are treated when their heroes were black, and the broad buffoonery of the song when the affair it celebrates was one that mainly concerned the masters. Hear, for example, through all the savage simplicity of the following rhymeless lines, the melancholy note that rises and falls but never intermits. The song is said to be very old, dating from the last century. It is still sung, but the Creole gentleman who procured it for me from a former slave was not able to transcribe or remember the air.

LUBIN.

Or notice again the stately tone of lamentation over the fate of a famous negro insurrectionist, as sung by old Madeleine of St. Bernard parish to the same Creole friend already mentioned, who kindly wrote down the lines on the spot for this collection. They are fragmentary, extorted by littles from the shattered memory of the ancient crone. Their allusion to the Cabildo places their origin in the days when that old colonial council administered Spanish rule over the province.

OUARRÀ ST. MALO.

Yé halé li la cyprier,

So bras yé ’tassé par derrier,

Yé ’tassé so la main divant;

Yé ’marré li apé queue choual,

Yé trainein li zouqu’à la ville.

Divant michés là dans Cabil’e

Yé

quisé

li li fé complot

Pou’ coupé cou à tout yé blancs.

Yé ’mandé li qui so compères;

Pôv’ St. Malo pas di’ a-rien!

Zize³¹ là li lir’ so la sentence,

Et pis³² li fé dressé potence.

Yé halé choual — ç’arette parti —

Pôv’ St. Malo resté pendi!

Eine hèr soleil deza levée

Quand yé pend li si la levée.

Yé laissé so corps balancé

Pou’ carancro gagnein manzé.

Yé halé li la cyprier,

So bras yé ’tassé par derrier,

Yé ’tassé so la main divant;

Yé ’marré li apé queue choual,

Yé trainein li zouqu’à la ville.

Divant michés là dans Cabil’e

Yé

quisé

li li fé complot

Pou’ coupé cou à tout yé blancs.

Yé ’mandé li qui so compères;

Pôv’ St. Malo pas di’ a-rien!

Zize³¹ là li lir’ so la sentence,

Et pis³² li fé dressé potence.

Yé halé choual — ç’arette parti —

Pôv’ St. Malo resté pendi!

Eine hèr soleil deza levée

Quand yé pend li si la levée.

Yé laissé so corps balancé

Pou’ carancro gagnein manzé.

THE DIRGE OF ST. MALO.

They hauled him from the cypress swamp. His arms they tied behind his back, They tied his hands in front of him; They tied him to a horse’s tail, They dragged him up into the town. Before those grand Cabildo men They charged that he had made a plot To cut the throats of all the whites. They asked him who his comrades were; Poor St. Malo said not a word! The judge his sentence read to him, And then they raised the gallows-tree. They drew the horse — the cart moved off — And left St. Malo hanging there. The sun was up an hour high When on the Levee he was hung; They left his body swinging there, For carrion crows to feed upon.

It would be curious, did the limits of these pages allow, to turn from such an outcry of wild mourning as this, and contrast with it the clownish flippancy with which the great events are sung, upon whose issue from time to time the fate of the whole land — society, government, the fireside, the lives of thousands — hung in agonies of suspense. At the same time it could not escape notice how completely in each case, while how differently in the two, the African has smitten his image into every line: in the one sort, the white, uprolled eyes and low wail of the savage captive, who dares not lift the cry of mourning high enough for the jealous ear of the master; in the other, the antic form, the grimacing face, the brazen laugh, and self-abasing confessions of the buffoon, almost within the whisk of the public jailer’s lash. I have before me two songs of dates almost fifty years apart. The one celebrates the invasion of Louisiana by the British under Admiral Cochrane and General Pakenham in 1814; the other, the capture and occupation of New Orleans by Commodore Farragut and General Butler in 1862.

It was on the morning of the twenty-third of December, 1814, that the British columns, landing from a fleet of barges and hurrying along the narrow bank of a small canal in a swamp forest, gained a position in the open plain on the banks of the Mississippi only six miles below New Orleans, and with no defenses to oppose them between their vantage-ground and the city. The surprise was so complete that, though they issued from the woods an hour before noon, it was nearly three hours before the news reached the town. But at nightfall General Jackson fell upon them and fought in the dark the engagement which the song commemorates, the indecisive battle of Chalmette.

The singer ends thus:

The story of Farragut’s victory and Butler’s advent in April, 1862, is sung with the still hghter heart of one in whose day the “quatre piquets” was no longer a feature of the calaboose. Its refrain is:

Qui ça qui rivé?

C’est Ferraguitt et p’i Botlair,

Qui rivé.”

The story is long and silly, much in the humor of

The dogs do bark.”

We will lay it on the table.

IV.

THE VOODOOS.

The dance and song entered into the negro worship. That worship was as dark and horrid as bestialized savagery could make the adoration of serpents. So revolting was it, and so morally hideous, that even in the West Indian French possessions a hundred years ago, with the slave-trade in full blast and the West Indian planter and slave what they were, the orgies of the Voodoos were forbidden. Yet both there and in Louisiana they were practiced.

The Aradas, St. Méry tells us, introduced them. They brought them from their homes beyond the Slave Coast, one of the most dreadfully benighted regions of all Africa. He makes the word Vaudaux. In Louisiana it is written Voudou and Voodoo, and is often changed on the negro’s lips to Hoodoo. It is the name of an imaginary being of vast supernatural powers residing in the form of a harmless snake. This spiritual influence or potentate is the recognized antagonist and opposite of Obi, the great African manitou or deity, or him whom the Congoes vaguely generalize as Zombi. In Louisiana, as I have been told by that learned Creole scholar the late Alexander Dimitry, Voodoo bore as a title of greater solemnity the additional name of Maignan, and that even in the Calinda dance, which he had witnessed innumerable times, was sometimes heard, at the height of its frenzy, the invocation—

Voodoo Magnan!”

The worship of Voodoo is paid to a snake kept in a box. The worshipers are not merely a sect, but in some rude, savage way also an order. A man and woman chosen from their own number to be the oracles of the serpent deity are called the king and queen. The queen is the more important of the two, and even in the present dilapidated state of the worship in Louisiana, where the king’s office has almost or quite disappeared, the queen is still a person of great note.

She reigns as long as she continues to live. She comes to power not by inheritance, but by election or its barbarous equivalent. Chosen for such qualities as would give her a natural supremacy, personal attractions among the rest, and ruling over superstitious fears and desires of every fierce and ignoble sort, she wields no trivial influence. I once saw, in her extreme old age, the famed Marie Laveau. Her dwelling was in the quadroon quarter of New Orleans, but a step or two from Congo Square, a small adobe cabin just off the sidewalk, scarcely higher than its close board fence, whose batten gate yielded to the touch and revealed the crazy doors and windows spread wide to the warm air, and one or two tawny faces within, whose expression was divided between a pretense of contemptuous inattention and a frowning resentment of the intrusion. In the center of a small room whose ancient cypress floor was worn with scrubbing and sprinkled with crumbs of soft brick—a Creole affectation of superior cleanliness—sat, quaking with feebleness in an ill-looking old rocking-chair, her body bowed, and her wild, gray witch’s tresses hanging about her shriveled, yellow neck, the queen of the Voodoos. Three generations of her children were within the faint beckon of her helpless, waggling wrist and fingers. They said she was over a hundred years old, and there was nothing to cast doubt upon the statement. She had shrunken away from her skin; it was like a turtle’s. Yet withal one could hardly help but see that the face, now so withered, had once been handsome and commanding. There was still a faint shadow of departed beauty on the forehead, the spark of an old fire in the sunken, glistening eyes, and a vestige of imperiousness in the fine, slightly aquiline nose, and even about her silent, woe-begone mouth. Her grandson stood by, an uninteresting quadroon between forty and fifty years old, looking strong, empty-minded, and trivial enough; but his mother, her daughter, was also present, a woman of some seventy years, and a most striking and majestic figure. In features, stature, and bearing she was regal. One had but to look on her, impute her brilliancies — too untamable and severe to be called charms or graces — to her mother, and remember what New Orleans was long years ago, to understand how the name of Marie Laveau should have driven itself inextricably into the traditions of the town and the times. Had this visit been postponed a few months it would have been too late. Marie Laveau is dead; Malvina Latour is queen. As she appeared presiding over a Voodoo ceremony on the night of the 23d of June, 1884, she is described as a bright mulattress of about forty-eight, of “extremely handsome figure,” dignified bearing, and a face indicative of a comparatively high order of intelligence. She wore a neat blue, white-dotted calico gown, and a “brilliant tignon (turban) gracefully tied.”

It is pleasant to say that this worship, in Louisiana, at least, and in comparison with what it once was, has grown to be a rather trivial afiair. The practice of its midnight forest rites seemed to sink into inanition along with Marie Laveau. It long ago diminished in frequency to once a year, the chosen night always being the Eve of St. John. For several years past even these annual celebrations have been suspended; but in the summer of 1884 they were — let it be hoped, only for the once — resumed.

When the queen decides that such a celebration shall take place, she appoints a night for the gathering, and some remote, secluded spot in the forest for the rendezvous. Thither all the worshipers are summoned. St. Méry, careless of the power of the scene, draws in practical, unimaginative lines the picture of such a gathering in St. Domingo, in the times when the “véritable Vaudaux” lost but little of the primitive African character. The worshipers are met, decked with kerchiefs more or less numerous, red being everywhere the predominating color. The king, abundantly adorned with them, wears one of pure red about his forehead as a diadem. A blue ornamental cord completes his insignia. The queen, in simple dress and wearing a red cord and a heavily decorated belt, is beside him near a rude altar. The silence of midnight is overhead, the gigantic forms and shadows and still, dank airs of the tropical forest close in around, and on the altar, in a small box ornamented with little tinkling bells, lies, unseen, the living serpent. The worshipers have begun their devotions to it by presenting themselves before it in a body, and uttering professions of their fidelity and belief in its power. They cease, and now the royal pair, in tones of parental authority and protection, are extolling the great privilege of being a devotee, and inviting the faithful to consult the oracle. The crowd makes room, and a single petitioner draws near. He is the senior member of the order. His prayer is made. The king becomes deeply agitated by the presence within him of the spirit invoked. Suddenly he takes the box from the altar and sets it on the ground. The queen steps upon it and with convulsive movements utters the answers of the deity beneath her feet. Another and another suppliant, approaching in the order of seniority, present, singly, their petitions, and humbly or exultingly, according to the nature of the responses, which hangs on the fierce caprice of the priestess, accept these utterances and make way for the next, with his prayer of fear or covetousness, love, jealousy, petty spite or deadly malice. At length the last petitioner is answered. Now a circle is formed, the caged snake is restored to the altar, and the humble and multifarious oblations of the worshipers are received, to be devoted not only to the trivial expenses of this worship, but also to the relief of members of the order whose distresses call for such aid. Again, the royal ones are speaking, issuing orders for execution in the future, orders that have not always in view, mildly says St. Méry, good order and public tranquillity. Presently the ceremonies become more forbidding. They are taking a horrid oath, smearing their lips with the blood of some slaughtered animal, and swearing to suffer death rather than disclose any secret of the order, and to inflict death on any who may commit such treason. Now a new applicant for membership steps into their circle, there are a few trivial formalities, and the Voodoo dance begins. The postulant dances frantically in the middle of the ring, only pausing from time to time to receive heavy alcoholic draughts in great haste and return more wildly to his leapings and writhings until he falls in convulsions. He is lifted, restored, and presently conducted to the altar, takes his oath, and by a ceremonial stroke from one of the sovereigns is admitted a full participant in the privileges and obligations of the devilish freemasonry. But the dance goes on about the snake. The contortions of the upper part of the body, especially of the neck and shoulders, are such as threaten to dislocate them. The queen shakes the box and tinkles its bells, the rum-bottle gurgles, the chant alternates between king and chorus —

There are swoonings and ravings, nervous tremblings beyond control, incessant writhings and turnings, tearing of garments, even biting of the flesh — every imaginable invention of the devil.

St. Méry tells us of another dance invented in the West Indies by a negro, analogous to the Voodoo dance, but more rapid, and in which dancers had been known to fall dead. This was the “Dance of Don Pedro.” The best efforts of police had, in his day, only partially suppressed it. Did it ever reach Louisiana? Let us, at a venture, say no.

To what extent the Voodoo worship still obtains here would be difficult to say with certainty. The affair of June, 1884, as described by Messrs. Augustin and Whitney, eye-witnesses, was an orgy already grown horrid enough when they turned their backs upon it. It took place at a wild and lonely spot where the dismal cypress swamp behind New Orleans meets the waters of Lake Pontchartrain in a wilderness of cypress stumps and rushes. It would be hard to find in nature a more painfully desolate region. Here in a fisherman’s cabin sat the Voodoo worshipers cross-legged on the floor about an Indian basket of herbs and some beans, some bits of bone, some oddly wrought bunches of feathers, and some saucers of small cakes. The queen presided, sitting on the only chair in the room. There was no king, no snake— at least none visible to the onlookers. Two drummers beat with their thumbs on gourds covered with sheepskin, and a white-wooled old man scraped that hideous combination of banjo and violin, whose head is covered with rattlesnake skin, and of which the Chinese are the makers and masters. There was singing— “M’alle couri dans deser” (“I am going into the wilderness”), a chant and refrain not worth the room they would take — and there was frenzy and a circling march, wild shouts, delirious gesticulations and posturings, drinking, and amongst other frightful nonsense the old trick of making fire blaze from the mouth by spraying alcohol from it upon the flame of a candle.

But whatever may be the quantity of the Voodoo worship left in Louisiana, its superstitions are many and are everywhere. Its charms are resorted to by the malicious, the jealous, the revengeful, or the avaricious, or held in terror, not by the timorous only, but by the strong, the courageous, the desperate. To find under his mattress an acorn hollowed out, stuffed with the hair of some dead person, pierced with four holes on four sides, and two small chicken feathers drawn through them so as to cross inside the acorn; or to discover on his door-sill at daybreak a little box containing a dough or waxen heart stuck full of pins; or to hear that his avowed foe or rival has been pouring cheap champagne in the four corners of Congo Square at midnight, when there was no moon, will strike more abject fear into the heart of many a stalwart negro or melancholy quadroon than to face a leveled revolver. And it is not only the colored man that holds to these practices and fears. Many a white Creole gives them full credence. What wonder, when African Creoles were the nurses of so nearly all of them? Many shrewd men and women, generally colored persons, drive a trade in these charms and in oracular directions for their use or evasion; many a Creole — white as well as other tints — female, too, as well as male— will pay a Voodoo “monteure” to “make a work,” i.e. to weave a spell, for the prospering of some scheme or wish too ignoble to be prayed for at any shrine inside the church. These milder incantations are performed within the witch’s or wizard’s own house, and are made up, for the most part, of a little pound cake, some lighted candle ends, a little syrup of sugar-cane, pins, knitting-needles, and a trifle of anisette. But fear naught; an Obi charm will enable you to smile defiance against all such mischief; or if you will but consent to be a magician, it is they, the Voodoos, one and all, who will hold you in absolute terror. Or, easier, a frizzly chicken! If you have on your premises a frizzly chicken, you can lie down and laugh—it is a checkmate!

A planter once found a Voodoo charm, or ouanga (wongah); this time it was a bit of cotton cloth folded about three cow-peas and some breast feathers of a barn-yard fowl, and covered with a tight wrapping of thread. When he proposed to take it to New Orleans his slaves were full of consternation. “Marse Ed, ef ye go on d’boat wid dat-ah, de boat’ll sink wi’ yer. Fore d’Lord, it will!” For some reason it did not. Here is a genuine Voodoo song, given me by Lafcadio Hearn, though what the words mean none could be more ignorant of than the present writer. They are rendered phonetically in French.

And another phrase : “Ah tingouai yé, Ah tingouai yé, Ah ouai ya, Ah ouai ya, Ah tin-gouai yé, Do sé dan go-do, Ah tingouai yé,” etc.

V.

SONGS OF WOODS AND WATERS.

A LAST page to the songs of the chase and of the boat. The circumstances that produced them have disappeared. There was a time, not so long ago, when travelling in Louisiana was done almost wholly by means of the paddle, the oar, or the “sweep.” Every plantation had its river or bayou front, and every planter his boat and skilled crew of black oarsmen. The throb of their song measured the sweep of the oars, and as their bare or turbaned heads and shining bodies, naked to the waist, bowed forward and straightened back in ceaseless alternation, their strong voices chanted the praise of the silent, broad-hatted master who sat in the stern. Now and then a line was interjected in manly boast to their own brawn, and often the praise of the master softened off into tender laudations of the charms of some black or tawny Zilie, ’Zabette, or Zalli. From the treasures of the old chest already mentioned comes to my hand, from the last century most likely, on a ragged yellow sheet of paper, written with a green ink, one of these old songs. It would take up much room; I have made a close translation of its stanzas:

ROWERS’ SONG.

From the same treasury comes a hunting song. Each stanza begins and ends with the loud refrain: “Bomboula! bomboula!” Some one who has studied African tongues may be able to say whether this word is one with Bamboula, the name of the dance and of the drum that dominates it. Oula seems to be an infinitve termination of many Congo verbs, and boula, De Lanzières says, means to beat. However, the dark hunters of a hundred years ago knew, and between their outcries of the loud, rumbling word sang, in this song, their mutual exhortation to rise, take guns, fill powder-horns, load up, call dogs, make haste and be off to the woods to find game for master’s table and their own grosser cuisine; for the one, deer, squirrels, rabbits, birds; for the other, chat oués (raccoons), that make “si bon gombo” (such good gumbo!). “Don’t fail to kill them, boys, — and the tiger-cats that eat men; and if we meet a bear, we’ll vanquish him! Bomboula! bomboula!” The lines have a fine African ring in them, but — one mustn’t print everything.

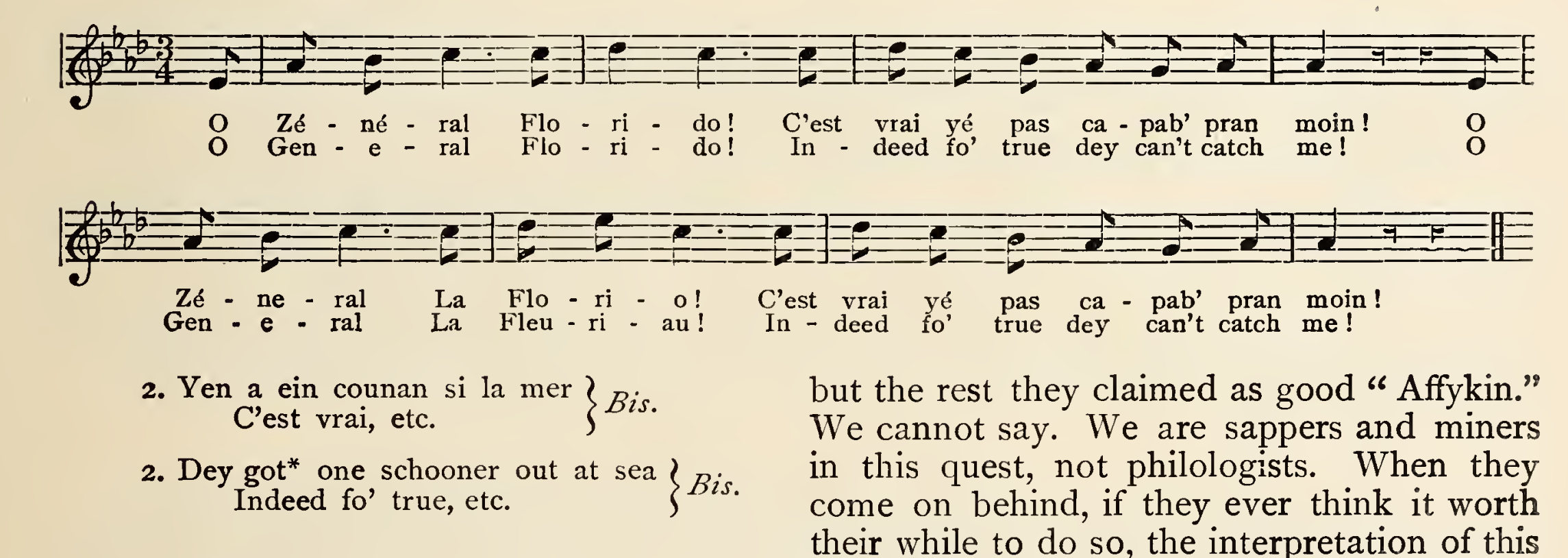

Another song, of wood and water both, though only the water is mentioned, I have direct from former Creole negro slaves. It is a runaway’s song of defiance addressed to the high sheriff Fleuriau (Charles Jean Baptiste Fleuriau, Alguazil mayor), a Creole of the Cabildo a hundred and fifteen years ago. At least one can think so, for the name isn’t to be found elsewhere.

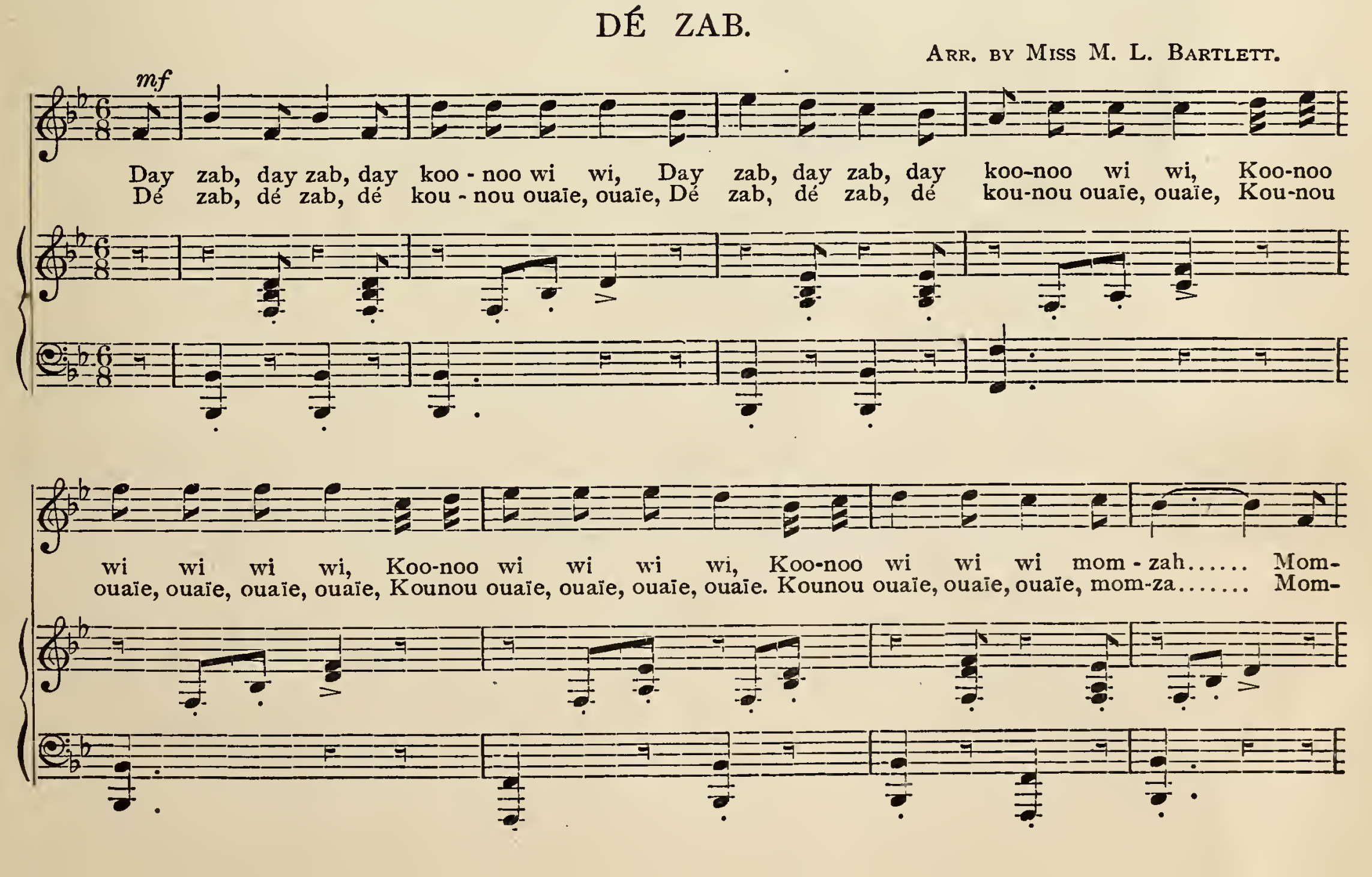

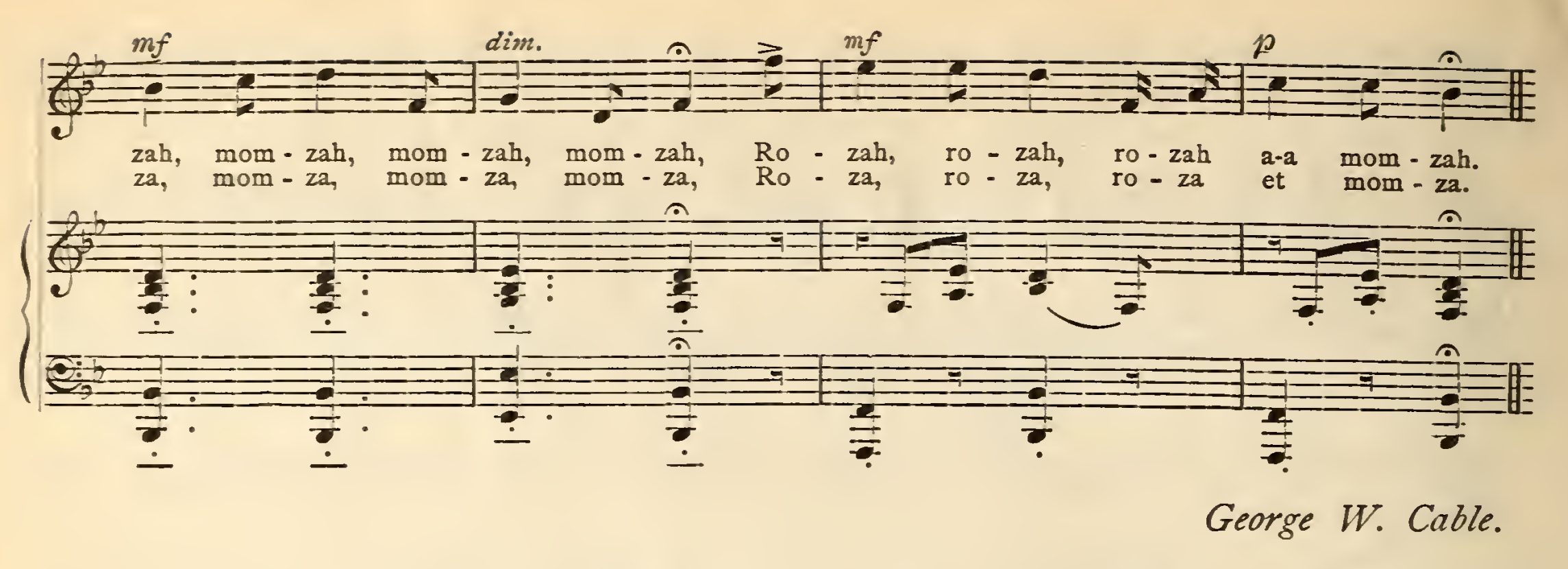

Sometimes the black man found it more convenient not to run away himself, but to make other articles of property seem to escape from custody. He ventured to forage on his own account, retaining his cabin as a base of operations, and seeking his adventures not so far from the hen-coop and pig-pen as rigid principles would have dictated. Now that he is free, he is willing to reveal these little pleasantries — as one of the bygones — to the eager historian. Much nocturnal prowling was done on the waters of the deep, forest-darkened bayous, in pirogues (dug-outs). For secret signals to accomplices on shore they resorted to singing. What is so innocent as music! The words were in some African tongue. We have one of these songs from the negroes themselves, with their own translation and their own assurance that the translation is correct. The words have a very Congo-ish sound. The Congo tongue knows no r; but the fact is familiar that in America the negro interchanges the sounds of r and l as readily as does the Chinaman. We will use both an English and a French spelling. (De Zab, page 827.)

The whole chant consists of but six words besides a single conjunction. It means, its singers avowed, “Out from under the trees our boat moves into the open water — bring us large game and small game!” Dé zab sounds like des arbs, and they called it French, but the rest they claimed as good “Affykin.” We cannot say. We are sappers and miners in this quest, not philologists. When they come on behind, if they ever think it worth their while to do so, the interpretation of this strange song may be not more difficult than that of the famous inscription discovered by Mr. Pickwick. But, as well as the present writer can know, all that have been given here are genuine antiques.

COMPENSATION.

Notes

- L’a’zane. L’argent — money. (Author’s note).

- Ç’at’. “We go to the other side” [of the river] “to get cats’ paws,” a delicious little blue swamp berry. (Author’s note).

- Patassa. Perch — The little sunfish or “pumpkin seed,” miscalled through the southwest. (Author’s note).

- Latanié, Dwarf palmetto, whose root is used by the Creoles as a scrubbing-brush. (Author’s note).

- Sougras. Pokebarries (Author’s note).

- Cancos. Indian name for a wild purple berry. (Author’s note).

- Zozos. Oiseaux, birds. (Author’s note).

- Nonpareil. Nonpareil, pape, or painted bunting, is the favorite victim of the youthful bird-trappers. (Author’s note).

- Chouals . Chevals — chevaux. (Author’s note).

- Macacs. Macaques. (Author’s note).

- Dos-brilé. “Gniapas là dotchians dos-brilé.” “Il n’y a pas là des dotchians avec les dos brulés.” The dotchian dos-brilé is the white trash with sunburnt back, the result of working in the fields. It is an expression of supreme contempt for the pitits blancs — low whites — to contrast them with the gros madames et gros michies. (Author’s note).

- Havano. To turn final a into o for the purpose of rhyme is the special delight of the singing negro. I used to hear as part of a moonlight game,— (Author’s note).

- Brid’e. Riding without e’er a saddle or bridle. (Author’s note).

- Beas’es. Beasts — wild animals. (Author’s note).

- Tremblant-terr’. Tremblement de terre — earthquake. (Author’s note).

- Chiel. Ciel. (Author’s note).

- Bourlé. Brulée. (Author’s note).

- Moun. Tout le monde. (Author’s note).

- Vend. Vendaient — sold, betrayed. (Author’s note).

- Saffaud. Echafaud. (Author’s note).

- La têtc. So la tête: Creole possessive form for his head. (Author’s note).

- Bitin. Butin: literally plunder, but used, as the word plunder is by the negro, for personal property. (Author’s note).

- Cofaire. Pourquoi faire. (Author’s note).

- Lavé. Washed (clothes). (Author’s note).

- Passé. Ironed. (Author’s note).

- Tassé. Attachée. (Author’s note).

- Marré. Amarré, an archaism, common to negroes and Acadians: moored, for fastened. (Author’s note).

- Quisé. Accusée. (Author’s note).

- Zize. Juge. (Author’s note).

- Pis. Puis. (Author’s note).

- Honc! “Hen! hen!” in St. Méry’s spelling of it for French pronunciation. As he further describes the sound in a foot-note, it must have been a horrid grunt. (Author’s note).

Text prepared by:

- Karla Garcia

- Ma’Asa Gay

- Jacob Harvey

Fall Quarter 2022:

- Anna Duck

- William Estabrook

Spring Quarter 2024:

- Danae Green

- Kaden Layne LaCaze

- Bruce R. Magee

- Khai Tran Nguyen

- Gia Kim Truong

Source

Cable, George Washington. “Creole Slave Songs.” The Century Magazine, XXXI (Apr. 1886), pp. 807-828. Internet Archive, https:// archive.org/ details/ creole slave songs 00cabl. Accessed 4 Aug. 2025.