Anthology

of Louisiana Literature

George Washington Cable.

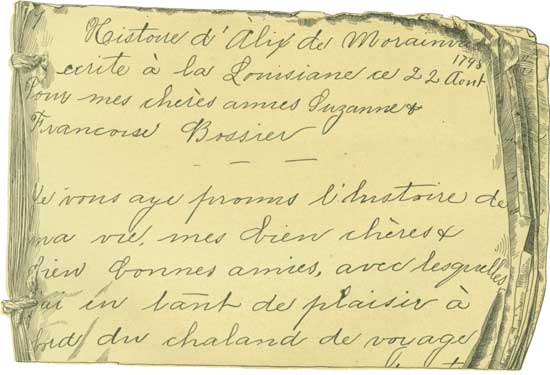

The Adventures of Françoise and Suzanne.

TO MY FRIEND JAMES BIRNEY GUTHRIE

| CONTENTS. |

| |

|

Page |

| I. |

The Two Sisters |

34 |

| II. |

Making Up The Expedition |

37 |

| III. |

The Embarkation |

43 |

| IV. |

Alix Carpentier |

51 |

| V. |

Down Bayou Plaquemine. — the Fight With Wild Nature |

55 |

| VI. |

The Twice-married Countess |

61 |

| VII. |

Odd Partners In The Bolero Dance |

65 |

| VIII. |

A Bad Storm In A Bad Place |

69 |

| IX. |

Maggie And The Robbers |

73 |

| X. |

Alix Puts Away The Past |

80 |

| XI. |

Alix Plays Fairy. — parting Tears. |

84 |

| XII. |

Little Paris |

90 |

| XIII. |

The Countess Madelaine |

94 |

| XIV. |

"Poor Little Alix!" |

99 |

| XV. |

The Discovery Of The Hat |

104 |

| XVI. |

The Ball |

108 |

| XVII. |

Picnic And Farewell |

116 |

THE ADVENTURES OF FRANÇOISE AND SUZANNE.

1795.

Years

passed by. Our war of the Revolution was over. The Indians

of

Louisiana and Florida were all greedy, smiling gift-takers of his

Catholic

Majesty. So were some others not Indians; and the Spanish

governors of

Louisiana, scheming with them for the acquisition of Kentucky and

the

regions intervening, had allowed an interprovincial commerce to

spring up.

Flatboats and barges came floating down the Mississippi past the

plantation home where little Suzanne and Françoise were

growing up to

womanhood. Many of the immigrants who now came to Louisiana were

the

royalist noblesse flying from the horrors of the French

Revolution.

Governor Carondelet was strengthening his fortifications around

New

Orleans; for Creole revolutionists had slipped away to Kentucky

and were

there plotting an armed descent in flatboats upon his little

capital,

where the rabble were singing the terrible songs of bloody Paris.

Agents

of the Revolution had come from France and so "contaminated," as

he says,

"the greater part of the province" that he kept order only "at the

cost

of sleepless nights, by frightening some, punishing others, and

driving

several out of the colony." It looks as though Suzanne had caught

a touch

of dis-relish for les aristocrates, whose necks the songs

of the day

were promising to the lampposts. To add to all these commotions, a

hideous

revolution had swept over San Domingo; the slaves in Louisiana had

heard

of it, insurrection was feared, and at length, in 1794, when

Susanne was

seventeen and Françoise fifteen, it broke out on the

Mississippi no great

matter over a day's ride from their own home, and twenty-three

blacks were

gibbeted singly at intervals all the way down by their father's

plantation

and on to New Orleans, and were left swinging in the weather to

insure the

peace and felicity of the land. Two other matters are all we need

notice

for the ready comprehension of Françoise's story.

Immigration was knocking

at every gate of the province, and citizen Étienne de

Boré had just made

himself forever famous in the history of Louisiana by producing

merchantable sugar; land was going to be valuable, even back on

the wild

prairies of Opelousas and Attakapas, where, twenty years before,

the

Acadians, — the cousins of Evangeline, — wandering from far Nova

Scotia, had

settled. Such was the region and such were the times when it began

to be

the year 1795.

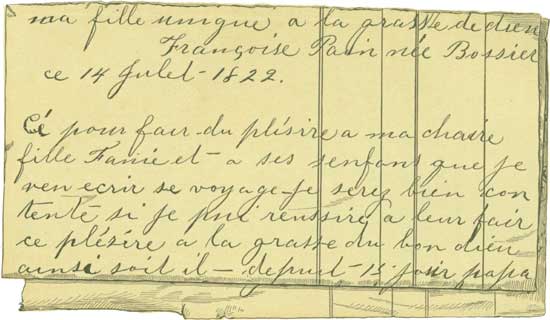

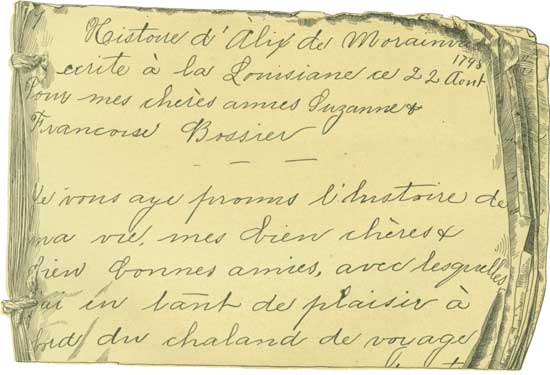

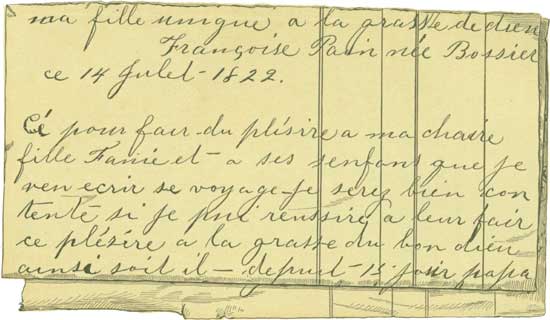

By good fortune one of the undestroyed fragments of

Françoise's own

manuscript is its first page. She was already a grandmother

forty-three

years old when in 1822 she wrote the tale she had so often told.

Part of

the dedication to her only daughter and namesake — one line,

possibly

two — has been torn off, leaving only the words, "ma fille unique a

la

grasse [meaning 'grace'] de dieu [sic]," over her signature and

the date,

"14 Julet [sic], 1822."

I.

THE TWO SISTERS.

It is to give pleasure to my dear daughter Fannie and to her

children that

I write this journey. I shall be well satisfied if I can succeed

in giving

them this pleasure: by the grace of God, Amen.

Papa, Mr. Pierre Bossier, planter of

St. James parish,

had been

fifteen

days gone to the city (New Orleans) in his skiff with two rowers,

Louis

and Baptiste, when, returning, he embraced us all, gave us some

caramels

which he had in his pockets, and announced that he counted on

leaving us

again in four or five days to go to Attakapas. He had long been

speaking

of going there. Papa and mamma were German, and papa loved to

travel. When

he first came to Louisiana it was with no expectation of staying.

But here

he saw mamma; he loved her, married her, and bought a very fine

plantation, where he cultivated indigo. You know they blue clothes

with

that drug, and dye cottonade and other things. There we, their

eight

children, were born. . . .

When my father used to go to New Orleans he went in his skiff,

with a

canopy over his head to keep off the sun, and two rowers, who sang

as

they rowed. Sometimes papa took me with him, and it was very

entertaining.

We would pass the nights of our voyage at the houses of papa's

friends

[des zami de papa]. Sometimes mamma would come, and Suzanne

always — always. She was the daughter next older than I. She barely

missed

being a boy. She was eighteen years of age, went hunting with our

father,

was skillful with a gun, and swam like a fish. Papa called her "my

son."

You must understand the two boys were respectively but two years

and three

months old, and papa, who greatly desired a son, had easily made

one of

Suzanne. My father had brought a few books with him to Louisiana,

and

among them, you may well suppose, were several volumes of travel.

For

myself, I rarely touched them; but they were the only books that

Suzanne

read. And you may well think, too, that my father had no sooner

spoken of

his intention than Suzanne cried:

"I am going with you, am I not, papa?"

"Naturally," replied my father; "and Françoise shall go

also."

Françoise — that was I; poor child of sixteen, who had but

six months

before quitted the school-bench, and totally unlike my

sister — blonde,

where Suzanne was dark; timid, even cowardly, while she had the

hardihood

and courage of a young lioness; ready to cry at sight of a wounded

bird,

while she, gun in hand, brought down as much game as the most

skillful

hunter.

I exclaimed at my father's speech. I had heard there were many

Indians in

Attakapas; the name means man-eaters. I have a foolish terror of

Indians,

and a more reasonable one for man-eaters. But papa and Suzanne

mocked at

my fears; and as, after all, I burned with desire for the journey,

it was

decided that I should go with them.

Necessarily we wanted to know how we were to go — whether we should

travel

by skiff, and how many negroes and negresses would go with us. For

you

see, my daughter, young people in 1795 were exactly what they are

in 1822;

they could do nothing by themselves, but must have a domestic to

dress and

undress them. Especially in traveling, where one had to take

clothes out

of trunks and put them back again, assistance became an absolute

necessity. Think, then, of our astonishment, of our vexation, when

papa

assured us that he would not take a single slave; that my sister

and I

would be compelled to help each other, and that the skiff would

remain

behind, tied up at the landing where it then lay.

"But explain yourself, Papa, I beg of you," cried Suzanne, with

her

habitual petulance.

"That is what I am trying to do," said he. "If you will listen in

silence,

I will give you all the explanation you want."

Here, my daughter, to save time, I will borrow my father's speech

and tell

of the trip he had made to New Orleans; how he had there found

means to

put into execution his journey to Attakapas, and the companions

that were

to accompany him.

II.

MAKING UP THE EXPEDITION.

In 1795 New Orleans was nothing but a mere market town. The

cathedral, the

convent of the Ursulines, five or six cafés, and about a

hundred houses

were all of it.

Can you believe, there were but two dry-goods stores!

And what fabulous prices we had to pay! Pins twenty dollars a

paper. Poor

people and children had to make shift with thorns of orange and

amourette [honey locust?]. A needle cost fifty cents, very

indifferent

stockings five dollars a pair, and other things accordingly.

On the levee was a little pothouse of the lowest sort; yet from

that

unclean and smoky hole was destined to come one of the finest

fortunes in

Louisiana. They called the proprietor

"Père la Chaise."

He was a

little

old marten-faced man, always busy and smiling, who every year laid

aside

immense profits. Along the crazy walls extended a few rough

shelves

covered with bottles and decanters. Three planks placed on boards

formed

the counter, with Père la Chaise always behind it. There

were two or three

small tables, as many chairs, and one big wooden bench. Here

gathered the

city's working-class, and often among them one might find a goodly

number

of the city's élite; for the wine and the beer of the old cabaretier

were famous, and one could be sure in entering there to hear all

the news

told and discussed.

By day the place was quiet, but with evening it became

tumultuous. Père la

Chaise, happily, did not lose his head; he found means to satisfy

all, to

smooth down quarrels without calling in the police, to get rid of

drunkards, and to make delinquents pay up.

My father knew the place, and never failed to pay it a visit when

he went

to New Orleans. Poor, dear father! he loved to talk as much as to

travel.

Père la Chaise was acquainted with him. One evening papa

entered, sat down

at one of the little tables, and bade Père la Chaise bring

a bottle of his

best wine. The place was already full of people, drinking,

talking, and

singing. A young man of twenty-six or twenty-seven entered almost

timidly

and sat down at the table where my father was — for he saw that all

the

other places were occupied — and ordered a half-bottle of cider. He

was a

Norman gardener. My father knew him by sight; he had met him here

several

times without speaking to him. You recognized the peasant at once;

and yet

his exquisite neatness, the gentleness of his face, distinguished

him from

his kind. Joseph Carpentier was

dressed

in a very ordinary gray woolen

coat; but his coarse shirt was very white, and his hair, when he

took off

his broad-brimmed hat, was well combed and glossy.

As Carpentier was opening his bottle a second frequenter entered

the

cabaret. This was a man of thirty or thirty-five, with

strong features

and the frame of a Hercules. An expression of frankness and gayety

overspread his sunburnt face. Cottonade pantaloons, stuffed into a

pair of

dirty boots, and a vareuse of the same stuff made up his

dress. His

vareuse, unbuttoned, showed his breast, brown and hairy; and a

horrid cap

with long hair covered, without concealing, a mass of red locks

that a

comb had never gone through. A long whip, the stock of which he

held in

his hand, was coiled about his left arm. He advanced to the

counter and

asked for a glass of brandy. He was a drayman named John Gordon — an

Irishman.

But, strange, John Gordon, glass in hand, did not drink;

Carpentier, with

his fingers round the neck of the bottle, failed to pour his

cider; and my

father himself, his eyes attracted to another part of the room,

forgot his

wine. Every one was looking at an individual gesticulating and

haranguing

in the middle of the place, to the great amusement of all. My

father

recognized him at first sight. He was an Italian about the age of

Gordon;

short, thick-set, powerful, swarthy, with the neck of a bull and

hair as

black as ebony. He was telling rapidly, with strong gestures, in

an almost

incomprehensible mixture of Spanish, English, French, and Italian,

the

story of a hunting party that he had made up five years before.

This was

Mario Carlo. A Neapolitan by birth, he had for several years

worked as a

blacksmith on the plantation of one of our neighbors, M. Alphonse

Perret.

Often papa had heard him tell of this hunt, for nothing could be

more

amusing than to listen to Carlo. Six young men, with Carlo as

sailor and

cook, had gone on a two-months' expedition into the country of the

Attakapas.

"Yes," said the Italian, in conclusion, "game never failed us;

deer,

turkeys, ducks, snipe, two or three bears a week. But the

sublimest thing

was the rich land. Ah! one must see it to believe it. Plains and

forests

full of animals, lakes and bayous full of fish. Ah! fortune is

there. For

five years I have dreamed, I have worked, with but one object in

view; and

today the end is reached. I am ready to go. I want only two

companions to

aid me in the long journey, and those I have come to look for

here."

John Gordon stepped forward, laid a hand upon the speaker's

shoulder, and

said:

"My friend, I am your man."

Mario Carlo seized the hand and shook it with all his force.

"You will not repent the step. But" — turning again to the

crowd — "we want

one more."

Joseph Carpentier rose slowly and advanced to the two men.

"Comrades, I

will be your companion if you will accept me."

Before separating, the three drank together and appointed to meet

the next

day at the house of Gordon, the Irishman.

When my father saw Gordon and Carpentier leave the place, he

placed his

hand on Mario's shoulder and said in Italian, "My boy, I want to

talk with

you."

At that time, as now, parents were very scrupulous as to the

society into

which they introduced their children, especially their daughters;

and papa

knew of a certain circumstance in Carlo's life to which my mother

might

greatly object. But he knew the man had an honest and noble heart.

He

passed his arm into the Italian's and drew him to the inn where my

father

was stopping, and to his room. Here he learned from Mario that he

had

bought one of those great barges that bring down provisions from

the West,

and which, when unloaded, the owners count themselves lucky to

sell at any

reasonable price. When my father proposed to Mario to be taken as

a

passenger the poor devil's joy knew no bounds; but it disappeared

when

papa added that he should take his two daughters with him.

The trouble was this: Mario was taking with him in his flatboat

his wife

and his four children; his wife and four children were

simply — mulattoes.

However, then as now, we hardly noticed those things, and the idea

never

entered our minds to inquire into the conduct of our slaves.

Suzanne and I

had known Celeste, Mario's wife, very well before her husband

bought her.

She had been the maid of Marianne Perret, and on great occasions

Marianne

had sent her to us to dress our hair and to prepare our toilets.

We were

therefore enchanted to learn that she would be with us on board

the

flatboat, and that papa had engaged her services in place of the

attendants we had to leave behind.

It was agreed that for one hundred dollars Mario Carlo would

receive all

three of us as passengers, that he would furnish a room simply but

comfortably, that papa would share this room with us, that Mario

would

supply our table, and that his wife would serve as maid and

laundress. It

remained to be seen now whether our other fellow-travelers were

married,

and, if so, what sort of creatures their wives were.

[The next day the four intended travelers met at Gordon's house.

Gordon

had a wife, Maggie, and a son, Patrick, aged twelve, as unlovely

in

outward aspect as were his parents. Carpentier, who showed himself

even

more plainly than on the previous night a man of native

refinement,

confessed to a young wife without offspring. Mario told his story

of love

and alliance with one as fair of face as he, and whom only cruel

law

forbade him to call wife and compelled him to buy his children;

and told

the story so well that at its close the father of Françoise

silently

grasped the narrator's hand, and Carpentier, reaching across the

table

where they sat, gave his, saying:

"You are an honest man, Monsieur Carlo."

"Will your wife think so?" asked the Italian.

"My wife comes from a country where there are no prejudices of

race."

Françoise takes the pains to say of this part of the story

that it was not

told her and Suzanne at this time, but years afterward, when they

were

themselves wives and mothers. When, on the third day, her father

saw

Carpentier's wife at the Norman peasant's lodgings, he was greatly

surprised at her appearance and manner, and so captivated by them

that he

proposed that their two parties should make one at table during

the

projected voyage — a proposition gratefully accepted. Then he left

New

Orleans for his plantation home, intending to return immediately,

leaving

his daughters in St. James to prepare for the journey and await

the

arrival of the flatboat, which must pass their home on its way to

the

distant wilds of Attakapas.]

III.

THE EMBARKATION.

You see, my dear child, at that time one post-office served for

three

parishes: St. James, St. John the Baptist, and St. Charles. It was

very

far from us, at the extremity of St. John the Baptist, and the

mail came

there on the first of each month.

We had to pay — though the price was no object — fifty cents postage

on a

letter. My father received several journals, mostly European.

There was

only one paper, French and Spanish, published in New Orleans —

"The Gazette."

To

send to the post-office was an affair of state. Our

father, you see, had not time to write; he was obliged to come to

us

himself. But such journeys were a matter of course in those days.

"And above all things, my children," said my father, "don't have

too much

baggage."

I should not have thought of rebelling; but Suzanne raised loud

cries,

saying it was an absolute necessity that we go with papa to New

Orleans,

so as not to find ourselves on our journey without

traveling-dresses, new

neckerchiefs, and a number of things. In vain did poor papa

endeavor to

explain that we were going into a desert worse than Arabia;

Suzanne put

her two hands to her ears and would hear nothing, until, weary of

strife,

poor papa yielded.

Our departure being decided upon, he wished to start even the

very next

day; and while we were instructing our sisters Elinore and Marie

concerning some trunks that we should leave behind us, and which

they must

pack and have ready for the flatboat, papa recommended to mamma a

great

slaughter of fowls, etc., and especially to have ready for

embarkation two

of our best cows. Ah! in those times if the planter wished to live

well he

had to raise everything himself, and the poultry yard and the

dairy were

something curious to see. Dozens of slaves were kept busy in them

constantly. When my mother had raised two thousand chickens,

besides

turkeys, ducks, geese, guinea-fowls, and pea-fowls, she said she

had

lost

her crop.

And the quantity of butter and cheese! And all this without

counting the sauces, the jellies, the preserves, the gherkins, the

syrups,

the brandied fruits. And not a ham, not a chicken, not a pound of

butter

was sold; all was served on the master's table, or, very often,

given to

those who stood in need of them. Where, now, can you find such

profusion?

Ah! commerce has destroyed industry.

The next day, after kissing mamma and the children, we got into

the large

skiff with papa and three days later stepped ashore in New

Orleans. We

remained there a little over a week, preparing our

traveling-dresses.

Despite the admonitions of papa, we went to the fashionable

modiste of the

day, Madame Cinthelia Lefranc, and ordered for each a suit that

cost one

hundred and fifty dollars. The costume was composed of a petticoat

of

camayeu, very short, caught up in puffs on the side by a

profusion of

ribbons; and a very long-pointed black velvet jacket (casaquin),

laced

in the back with gold and trimmed on the front with several rows

of gilt

buttons. The sleeves stopped at the elbows and were trimmed with

lace.

Now, my daughter, do you know what camayeu was? You now sometimes

see an

imitation of it in door and window curtains. It was a stuff of

great

fineness, yet resembling not a little the unbleached cotton of

to-day, and

over which were spread very brilliant designs of prodigious size.

For

example, Suzanne's petticoat showed bunches of great radishes — not

the

short kind — surrounded by long, green leaves and tied with a yellow

cord;

while on mine were roses as big as a baby's head, interlaced with

leaves

and buds and gathered into bouquets graced with a blue ribbon. It

was ten

dollars an ell; but, as the petticoats were very short, six ells

was

enough for each. At that time real hats were unknown. For driving

or for

evening they placed on top of the high, powdered hair what they

called a

catogan, a little bonnet of gauze or lace trimmed with

ribbons; and

during the day a sun-bonnet of silk or velvet. You can guess that

neither

Suzanne nor I, in spite of papa's instructions, forgot these.

Our traveling-dresses were gray cirsacas, — the skirt all

one, short,

without puffs; the jacket coming up high and with long sleeves, — a

sunbonnet of cirsacas, blue stockings, embroidered handkerchief or

blue

cravat about the neck, and high-heeled shoes.

As soon as Celeste heard of our arrival in New Orleans she

hastened to us.

She was a good creature; humble, respectful, and always ready to

serve.

She was an excellent cook and washer, and, what we still more

prized, a

lady's maid and hairdresser of the first order. My sister and I

were glad

to see her, and overwhelmed her with questions about Carlo, their

children, their plans, and our traveling companions.

"Ah! Momzelle Suzanne, the little Madame Carpentier seems to me a

fine

lady, ever so genteel; but the Irish woman! Ah! grand Dieu!

she puts me

in mind of a soldier. I'm afraid of her. She smokes — she swears — she

carries a pistol, like a man."

At last the 15th of May came, and papa took us on board the

flatboat and

helped us to find our way to our apartment. If my father had

allowed

Carlo, he would have ruined himself in furnishing our room; but

papa

stopped him and directed it himself. The flatboat had been divided

into

four chambers. These were covered by a slightly arching deck, on

which the

boat was managed by the moving of immense sweeps that sent her

forward.

The room in the stern, surrounded by a sort of balcony, which

Monsieur

Carpentier himself had made, belonged to him and his wife; then

came ours,

then that of Celeste and her family, and the one at the bow was

the

Irishwoman's. Carlo and Gordon had crammed the provisions, tools,

carts,

and plows into the corners of their respective apartments. In the

room

which our father was to share with us he had had Mario make two

wooden

frames mounted on feet. These were our beds, but they were

supplied with

good bedding and very white sheets. A large cypress table, on

which we saw

a pile of books and our workboxes; a washstand, also of cypress,

but well

furnished and surmounted by a mirror; our trunks in a corner;

three

rocking-chairs — this was all our furniture. There was neither

carpet nor

curtain.

All were on board except the Carpentier couple. Suzanne was all

anxiety to

see the Irishwoman. Poor Suzanne! how distressed she was not to be

able to

speak English! So, while I was taking off my capotte — as

the sun-bonnet

of that day was called — and smoothing my hair at the glass, she had

already tossed her capotte upon papa's bed and sprung up the

ladder that

led to the deck. (Each room had one.) I followed a little later

and had

the satisfaction of seeing Madame Margaretto Gordon, commonly

called

"Maggie" by her husband and "Maw" by her son Patrick. She was

seated on a

coil of rope, her son on the boards at her feet. An enormous dog

crouched

beside them, with his head against Maggie's knee. The mother and

son were

surprisingly clean. Maggie had on a simple brown calico dress and

an

apron of blue ticking. A big red kerchief was crossed on her

breast and

its twin brother covered her well combed and greased black hair.

On her

feet were blue stockings and heavy leather shoes. The blue ticking

shirt

and pantaloons and waistcoat of Master Pat were so clean that they

shone;

his black cap covered his hair — as well combed as his mother's; but

he was

barefooted. Gordon, Mario, and Celeste's eldest son, aged

thirteen, were

busy about the deck; and papa, his cigar in his mouth and his

hands in his

pockets, stood looking out on the levee. I sat down on one of the

rough

benches that had been placed here and there, and presently my

sister came

and sat beside me.

"Madame Carpentier seems to be a laggard," she said. She was

burning to

see the arrival of her whom we had formed the habit of calling

"the little

French peasant."

[Presently Suzanne begins shooting bonbons at little Patrick,

watching the

effect out of the corners of her eyes, and by and by gives that

smile, all

her own, — to which, says Françoise, all flesh invariably

surrendered, — and

so became dumbly acquainted; while Carlo was beginning to swear

"fit to

raise the dead," writes the memoirist, at the tardiness of the

Norman

pair. But just then — ]

A carriage drove up to within a few feet of our chaland

and Joseph

Carpentier alighted, paid the driver, and lifted from it one so

delicate,

pretty, and small that you might take her at first glance for a

child of

ten years. Suzanne and I had risen quickly and came and leaned

over the

balustrade. To my mortification my sister had passed one arm

around the

waist of the little Irishman and held one of his hands in hers.

Suzanne

uttered a cry of astonishment. "Look, look, Françoise!" But

I was looking,

with eyes wide with astonishment.

The gardener's wife had alighted, and with her little gloved hand

shook

out and re-arranged her toilet. That toilet, very simple to the

eyes of

Madame Carpentier, was what petrified us with astonishment. I am

going to

describe it to you, my daughter.

We could not see her face, for her hood of blue silk, trimmed

with a light

white fur, was covered with a veil of white lace that entirely

concealed

her features. Her traveling-dress, like ours, was of cirsacas, but

ours

was cotton, while hers was silk, in broad rays of gray and blue;

and as

the weather was a little cool that morning, she had exchanged the

unfailing casaquin for a sort of camail to match the

dress, and trimmed,

like the capotte, with a line of white fur. Her petticoat was very

short,

lightly puffed on the sides, and ornamented only with two very

long

pockets trimmed like the camail. Below the folds of the robe were

two

Cinderella feet in blue silk stockings and black velvet slippers.

It was

not only the material of this toilet that astonished us, but the

way in

which it was made.

"Maybe she is a modiste. Who knows?" whispered Suzanne.

Another thing: Madame Carpentier wore a veil and gloves, two

things of

which we had heard but which we had never seen. Madame Ferrand had

mentioned them, but said that they sold for their weight in gold

in Paris,

and she had not dared import them, for fear she could not sell

them in

Louisiana. And here was the wife of a laboring gardener, who

avowed

himself possessor of but two thousand francs, dressed like a

duchess and

with veil and gloves!

I could but notice with what touching care Joseph assisted his

wife on

board. He led her straight to her room, and quickly rejoined us on

deck to

put himself at the disposition of his associates. He explained to

Mario

his delay, caused by the difficulty of finding a carriage; at

which Carlo

lifted his shoulders and grimaced. Joseph added that madame — I

noticed

that he rarely called her Alix — was rather tired, and would keep

her room

until dinner time. Presently our heavy craft was under way.

Pressing against the long sweeps, which it required a herculean

strength

to move, were seen on one side Carlo and his son Celestino, or

'Tino, and

on the other Joseph and Gordon. It moved slowly; so slowly that it

gave

the effect of a great tortoise.

IV.

ALIX CARPENTIER.

Towards noon we saw Celeste come on deck with her second son,

both

carrying baskets full of plates, dishes, covers, and a tablecloth.

You

remember I have often told you of an awning stretched at the stern

of the

flatboat? We found that in fine weather our dining-room was to be

under

this. There was no table; the cloth was simply spread on the deck,

and

those who ate had to sit à la Turque or take their

plates on their

knees. The Irish family ate in their room. Just as we were drawing

around

our repast Madame Carpentier, on her husband's arm, came up on

deck.

Dear little Alix! I see you yet as I saw you then. And here,

twenty-seven

years after our parting, I have before me the medallion you gave

me, and

look tenderly on your dear features, my friend!

She had not changed her dress; only she had replaced her camail

with a

scarf of blue silk about her neck and shoulders and had removed

her gloves

and capuche. Her rich chestnut hair, unpowdered, was

combed back à la

Chinoise, and the long locks that descended upon her

shoulders were tied

by a broad blue ribbon forming a rosette on the forepart of her

head. She

wore no jewelry except a pearl at each ear and her wedding ring.

Suzanne,

who always saw everything, remarked afterward that Madame

Carpentier wore

two.

"As for her earrings," she added, "they are nothing great.

Marianne has

some as fine, that cost, I think, ten dollars."

Poor Suzanne, a judge of jewelry! Madame Carpentier's earrings

were two

great pearls, worth at least two hundred dollars. Never have I met

another

so charming, so lovely, as Alix Carpentier. Her every movement was

grace.

She moved, spoke, smiled, and in all things acted differently from

all the

women I had ever met until then. She made one think she had lived

in a

world all unlike ours; and withal she was simple, sweet, good, and

to love

her seemed the most natural thing on earth. There was nothing

extraordinary in her beauty; the charm was in her intelligence and

her

goodness.

Maggie, the Irishwoman, was very taciturn. She never mingled with

us, nor

spoke to any one except Suzanne, and to her in monosyllables only

when

addressed. You would see her sometimes sitting alone at the bow of

the

boat, sewing, knitting, or saying her beads. During this last

occupation

her eyes never quitted Alix. One would say it was to her she

addressed her

prayers; and one day, when she saw my regard fixed upon Alix, she

said to

me:

"It does me good to look at her; she must look like the Virgin

Mary."

Her little form, so graceful and delicate, had, however, one

slight

defect; but this was hidden under the folds of her robe or of the

scarf

that she knew how to arrange with such grace. One shoulder was a

trifle

higher than the other.

After having greeted my father, whom she already knew, she turned

to us,

hesitated a moment, and then, her two little hands extended, and

with a

most charming smile, she advanced, first to me and then to

Suzanne, and

embraced us both as if we had been old acquaintances. And from

that moment

we were good friends.

It had been decided that the boat should not travel by night,

notwithstanding the assurance of Carlo, who had a map of

Attakapas. But in

the Mississippi there was no danger; and as papa was pressed to

reach our

plantation, we traveled all that first night.

The next day Alix — she required us to call her by that

name — invited us to

visit her in her room. Suzanne and I could not withhold a cry of

surprise

as we entered the little chamber. (Remember one thing: papa took

nothing

from home, not knowing even by what means we should return; but

the

Carpentiers were going for good and taking everything.) Joseph had

had the

rough walls whitewashed. A cheap carpet — but high-priced in those

times — of bright colors covered the floor; a very low French bed

occupied

one corner, and from a sort of dais escaped the folds of an

embroidered

bobbinet mosquito-bar. It was the first mosquito-bar of that kind

we had

ever seen. Alix explained that she had made it from the curtains

of the

same bed, and that both bed and curtains she had brought with her

from

England. New mystery!

Beside the bed a walnut dressing-table and mirror, opposite to it

a

washstand, at the bed's foot a príedieu, a

center-table, three

chairs — these were all the furniture; but [an enumeration follows

of all

manner of pretty feminine belongings, in crystal, silver, gold,

with a

picture of the crucifixion and another of the Virgin]. On the

shelves were

a rich box of colors, several books, and some portfolios of music.

From a

small peg hung a guitar.

But Suzanne was not satisfied. Her gaze never left an object of

unknown

form enveloped in green serge. Alix noticed, laughed, rose, and,

lifting

the covering, said:

"This is my harp, Suzanne; later I will play it for you."

The second evening and those that followed, papa, despite Carlo's

representation and the magnificent moonlight, opposed the

continuation of

the journey by night; and it was not until the morning of the

fifth day

that we reached St. James.

You can fancy the joy with which we were received at the

plantation. We

had but begun our voyage, and already my mother and sisters ran to

us with

extended arms as though they had not seen us for years. Needless

to say,

they were charmed with Alix; and when after dinner we had to say a

last

adieu to the loved ones left behind, we boarded the flatboat and

left the

plantation

amid huzzas,

waving handkerchiefs, and kisses

thrown from

finger-tips. No one wept, but in saying good-bye to my father, my

mother

asked:

"Pierre, how are you going to return?"

"Dear wife, by the mercy of God all things are possible to the

man with

his pocket full of money."

During the few days that we passed on the Mississippi each day

was like

the one before. We sat on the deck and watched the slow swinging

of the

long sweeps, or read, or embroidered, or in the chamber of Alix

listened

to her harp or guitar; and at the end of another week, we arrived

at

Plaquemine.

V.

DOWN BAYOU PLAQUEMINE — THE FIGHT

WITH WILD NATURE.

Plaquemine was composed of a church, two stores, as many

drinking-shops,

and about fifty cabins, one of which was the court-house. Here

lived a

multitude of Catalans, Acadians, negroes, and Indians. When

Suzanne and

Maggie, accompanied by my father and John Gordon, went ashore, I

declined

to follow, preferring to stay aboard with Joseph and Alix. It was

at

Plaquemine that we bade adieu to the old Mississippi. Here our

flatboat

made a détour and entered

Bayou Plaquemine.

Hardly had we started when our men saw and were frightened by the

force of

the current. The enormous flatboat, that Suzanne had likened to a

giant

tortoise, darted now like an arrow, dragged by the current. The

people of

Plaquemine had forewarned our men and recommended the greatest

prudence.

"Do everything possible to hold back your boat, for if you strike

any of

those tree-trunks of which the bayou is full it would easily sink

you."

Think how reassuring all this was, and the more when they informed

us that

this was the first time a flatboat had ventured into the bayou!

Mario, swearing in all the known languages, sought to reassure

us, and,

aided by his two associates, changed the manoeuvring, and with

watchful

eye found ways to avoid the great uprooted trees in which the

lakes and

bayous of Attakapas abound. But how clouded was Carpentier's brow!

And my

father? Ah! he repented enough. Then he realized that gold is not

always

the vanquisher of every obstacle. At last, thanks to Heaven, our

flatboat

came off victor over the snags, and after some hours we arrived at

the

Indian village of which you have heard me tell.

If I was afraid at sight of a dozen savages among the Spaniards

of

Plaquemine, what was to become of me now? The bank was entirely

covered

with men, their faces painted, their heads full of feathers,

moccasins on

their feet, and bows on shoulder — Indians indeed, with women simply

wrapped in blankets, and children without the shadow of a garment;

and all

these Indians running, calling to one another, making signs to us,

and

addressing us in incomprehensible language. Suzanne, standing up

on the

bow of the flatboat, replied to their signs and called with all

the force

of her lungs every Indian word that — God knows where — she had

learned:

"Chacounam finnan! O Choctaw! Conno Poposso!" And the Indians

clapped

their hands, laughing with pleasure and increasing yet more their

gestures

and cries.

The village, about fifty huts, lay along the edge of the water.

The

unfortunates were not timid. Presently several came close to the

flatboat

and showed us two deer and some wild turkeys and ducks, the spoils

of

their hunting. Then came the women laden with sacks made of bark

and full

of blackberries, vegetables, and a great quantity of baskets;

showing all,

motioning us to come down, and repeating in French and Spanish,

"Money,

money!"

It was decided that Mario and Gordon should stay on board and

that all the

rest of the joyous band should go ashore. My father, M.

Carpentier, and

'Tino loaded their pistols and put them into their belts. Suzanne

did

likewise, while Maggie called Tom, her bulldog, to follow her.

Celeste

declined to go, because of her children. As to Alix and me, a

terrible

contest was raging in us between fright and curiosity, but the

latter

conquered. Suzanne and papa laughed so about our fears that Alix,

less

cowardly than I, yielded first, and joined the others. This was

too much.

Grasping my father's arm and begging him not to leave me for an

instant, I

let him conduct me, while Alix followed me, taking her husband's

arm in

both her hands. In front marched 'Tino, his gun on his shoulder;

after him

went Maggie, followed by Tom; and then Suzanne and little Patrick,

inseparable friends.

Hardly had we gone a few steps when we were surrounded by a human

wall,

and I realized with a shiver how easy it would be for these

savages to get

rid of us and take all our possessions. But the poor devils

certainly

never thought of it: they showed us their game, of which papa

bought the

greater part, as well as several sacks of berries, and also

vegetables.

But the baskets! They were veritable wonders. As several of those

that I

bought that day are still in your possession, I will not lose much

time

telling of them. How those half-savage people could make things so

well

contrived and ornamented with such brilliant colors is still a

problem to

us. Papa bought for mamma thirty-two little baskets fitting into

one

another, the largest about as tall as a child of five years, and

the

smallest just large enough to receive a thimble. When he asked the

price I

expected to hear the seller say at least thirty dollars, but his

humble

reply was five dollars. For a deer he asked one dollar; for a wild

turkey,

twenty-five cents. Despite the advice of papa, who asked us how we

were

going to carry our purchases home, Suzanne and I bought, between

us, more

than forty baskets, great and small. To papa's question, Suzanne

replied

with an arch smile:

"God will provide."

Maggie and Alix also bought several; and Alix, who never forgot

any one,

bought two charming little baskets that she carried to Celeste.

Each of

us, even Maggie, secured a broad parti-colored mat to use on the

deck as

a couch à la Turque. Our last purchases were two

Indian bows painted red

and blue and adorned with feathers; the first bought by Celestino

Carlo,

and the other by Suzanne for her chevalier, Patrick Gordon.

An Indian woman who spoke a little French asked if we would not

like to

visit the queen. We assented, and in a few moments she led us into

a hut

thatched with palmetto leaves and in all respects like the others.

Its

interior was disgustingly unclean. The queen was a woman quite or

nearly a

hundred years old. She sat on a mat upon the earth, her arms

crossed on

her breast, her eyes half closed, muttering between her teeth

something

resembling a prayer. She paid no attention to us, and after a

moment we

went out. We entered two or three other huts and found the same

poverty

and squalor. The men did not follow us about, but the women — the

whole

tribe, I think — marched step by step behind us, touching our

dresses, our

capuches, our jewelry, and asking for everything; and I

felt well

content when, standing on our deck, I could make them our last

signs of

adieu.

Our flatboat moved ever onward. Day by day, hour by hour, every

minute it

advanced — slowly it is true, in the diminished current, but it

advanced. I

no longer knew where I was. We came at times where I thought we

were lost;

and then I thought of mamma and my dear sisters and my two pretty

little

brothers, whom I might never see again, and I was swallowed up.

Then

Suzanne would make fun of me and Alix would caress me, and that

did me

good. There were many bayous, — a labyrinth, as papa said, — and Mario

had

his map at hand showing the way. Sometimes it seemed

impracticable, and it

was only by great efforts of our men ["no zomme," says the

original] that

we could pass on. One thing is sure — those who traverse those same

lakes

and bayous to-day have not the faintest idea of what they were [il

zété]

in 1795.

Great vines hung down from lofty trees that shaded the banks and

crossed

one another a hundred — a thousand — ways to prevent the boat's

passage and

retard its progress, as if the devil himself was mixed in it; and,

frankly, I believe that he had something to do with us in that

cavern.

Often our emigrants were forced to take their axes and hatchets in

hand to

open a road. At other times tree-trunks, heaped upon one another,

completely closed a bayou. Then think what trouble there was to

unbar that

gate and pass through. And, to make all complete, troops of hungry

alligators clambered upon the sides of our flatboat with jaws open

to

devour us. There was much outcry; I fled, Alix fled with me,

Suzanne

laughed. But our men were always ready for them with their guns.

VI.

THE TWICE-MARRIED COUNTESS.

But with all the sluggishness of the flatboat, the toils, the

anxieties,

and the frights, what happy times, what gay moments, we passed

together on

the rough deck of our rude vessel, or in the little cells that we

called

our bedrooms.

It was in these rooms, when the sun was hot on deck, that my

sister and I

would join Alix to learn from her a new stitch in embroidery, or

some of

the charming songs she had brought from France and which she

accompanied

with harp or guitar.

Often she read to us, and when she grew tired put the book into

my hands

or Suzanne's, and gave us precious lessons in reading, as she had

in

singing and in embroidery. At times, in these moments of intimacy,

she

made certain half-disclosures that astonished us more and more.

One day

Suzanne took between her own two hands that hand so small and

delicate and

cried out all at once:

"How comes it, Alix, that you wear two wedding rings?"

"Because," she sweetly answered, "if it gives you pleasure to

know, I have

been twice married."

We both exclaimed with surprise.

"Ah!" she said, "no doubt you think me younger [bocou plus jeune]

than I

really am. What do you suppose is my age?"

Suzanne replied: "You look younger than Françoise, and she

is sixteen."

"I am twenty-three," replied Alix, laughing again and again.

Another time my sister took a book, haphazard, from the shelves.

Ordinarily [audinaremend] Alix herself chose our reading, but she

was busy

embroidering. Suzanne sat down and began to read aloud a romance

entitled

"Two Destinies."

"Ah!" cried my sister, "these two girls must be Françoise

and I."

"Oh no, no!" exclaimed Alix, with a heavy sigh, and Suzanne began

her

reading. It told of two sisters of noble family. The elder had

been

married to a count, handsome, noble, and rich; and the other,

against her

parents' wish, to a poor workingman who had taken her to a distant

country, where she died of regret and misery. Alix and I listened

attentively; but before Suzanne had finished, Alix softly took the

book

from her hands and replaced it on the shelf.

"I would not have chosen that book for you; it is full of

exaggerations

and falsehoods."

"And yet," said Suzanne, "see with what truth the lot of the

countess is

described! How happy she was in her emblazoned coach, and her

jewels, her

laces, her dresses of velvet and brocade! Ah, Françoise! of

the two

destinies I choose that one."

Alix looked at her for a moment and then dropped her head in

silence.

Suzanne went on in her giddy way:

"And the other: how she was punished for her plebeian tastes!"

"So, my dear Suzanne," responded Alix, "you would not marry — "

"A man not my equal — a workman? Ah! certainly not."

Madame Carpentier turned slightly pale. I looked at Suzanne with

eyes full

of reproach; and Suzanne remembering the gardener, at that moment

in his

shirt sleeves pushing one of the boat's long sweeps, bit her lip

and

turned to hide her tears. But Alix — the dear little creature! — rose,

threw

her arms about my sister's neck, kissed her, and said:

"I know very well that you had no wish to give me pain, dear

Suzanne. You

have only called up some dreadful things that I am trying to

forget. I am

the daughter of a count. My childhood and youth were passed in

châteaux

and palaces, surrounded by every pleasure that an immense fortune

could

supply. As the wife of a viscount I have been received at court; I

have

been the companion of princesses. To-day all that is a dreadful

dream.

Before me I have a future the most modest and humble. I am the

wife of

Joseph the gardener; but poor and humble as is my present lot, I

would not

exchange it for the brilliant past, hidden from me by a veil of

blood and

tears. Some day I will write and send you my history; for I want

to make

it plain to you, Suzanne, that titles and riches do not make

happiness,

but that the poorest fate illumined by the fires of love is very

often

radiant with pleasure."

We remained mute. I took Alix's hand in mine and silently pressed

it. Even

Suzanne, the inquisitive Suzanne, spoke not a word. She was

content to

kiss Alix and wipe away her tears.

If the day had its pleasures, it was in the evenings, when we

were all

reunited on deck, that the moments of gayety began. When we had

brilliant

moonlight the flatboat would continue its course to a late hour.

Then, in

those calm, cool moments, when the movement of our vessel was so

slight

that it seemed to slide on the water, amid the odorous breezes of

evening,

the instruments of music were brought upon deck and our concerts

began. My

father played the flute delightfully; Carlo, by ear, played the

violin

pleasantly; and there, on the deck of that old flatboat, before an

indulgent audience, our improvised instruments waked the sleeping

creatures of the centuries-old forest and called around us the

wondering

fishes and alligators. My father and Alix played admirable duos on

flute

and harp, and sometimes Carlo added the notes of his violin or

played for

us cotillons and Spanish dances. Finally Suzanne and I, to please

papa,

sang together Spanish songs, or songs of the negroes, that made

our

auditors nearly die a-laughing; or French ballads, in which Alix

would

mingle her sweet voice. Then Carlo, with gestures that always

frightened

Patrick, made the air resound with Italian refrains, to which

almost

always succeeded the Irish ballads of the Gordons.

But when it happened that the flatboat made an early stop to let

our men

rest, the programme was changed. Celeste and Maggie went ashore to

cook

the two suppers there. Their children gathered wood and lighted

the

fires. Mario and Gordon, or Gordon and 'Tino, went into the forest

with

their guns. Sometimes my father went along, or sat down by M.

Carpentier,

who was the fisherman. Alix, too, generally sat near her husband,

her

sketch-book on her knee, and copied the surrounding scene. Often,

tired of

fishing, we gathered flowers and wild fruits. I generally staid

near Alix

and her husband, letting Suzanne run ahead with Patrick and Tom.

It was a

strange thing, the friendship between my sister and this little

Irish boy.

Never during the journey did he address one word to me; he never

answered

a question from Alix; he ran away if my father or Joseph spoke to

him; he

turned pale and hid if Mario looked at him. But with Suzanne he

talked,

laughed, obeyed her every word, called her Miss Souzie, and was

never so

happy as when serving her. And when, twenty years afterward, she

made a

journey to Attakapas, the wealthy M. Patrick Gordon, hearing by

chance of

her presence, came with his daughter to make her his guest for a

week,

still calling her Miss Souzie, as of old.

VII.

ODD PARTNERS IN THE BOLERO DANCE.

Only one thing we lacked — mass and Sunday prayers. But on that day

the

flatboat remained moored, we put on our Sunday clothes, gathered

on deck,

and papa read the mass aloud surrounded by our whole party,

kneeling; and

in the parts where the choir is heard in church, Alix, my sister,

and I,

seconded by papa and Mario, sang hymns.

One evening — we had already been five weeks on our journey — the

flatboat

was floating slowly along, as if it were tired of going, between

the

narrow banks of a bayou marked in red ink on Carlo's map, "Bayou

Sorrel."

It was about six in the afternoon. There had been a suffocating

heat all

day. It was with joy that we came up on deck. My father, as he

made his

appearance, showed us his flute. It was a signal: Carlo ran for

his

violin, Suzanne for Alix's guitar, and presently Carpentier

appeared with

his wife's harp. Ah! I see them still: Gordon and 'Tino seated on

a mat;

Celeste and her children; Mario with his violin; Maggie; Patrick

at the

feet of Suzanne; Alix seated and tuning her harp; papa at her

side; and M.

Carpentier and I seated on the bench nearest the musicians.

My father and Alix had already played some pieces, when papa

stopped and

asked her to accompany him in a new bolero which was then the

vogue in New

Orleans. In those days, at all the balls and parties, the boleros,

fandangos, and other Spanish dances had their place with the

French

contra-dances and waltzes. Suzanne had made her entrance into

society

three years before, and danced ravishingly. Not so with me. I had

attended

my first ball only a few months before, and had taken nearly all

my

dancing-lessons from Suzanne. What was to become of me, then, when

I heard

my father ask me to dance the bolero which he and Alix were

playing!. . .

Every one made room for us, crying, "Oh, oui, Mlle. Suzanne;

dancez! Oh,

dancez, Mlle. Françoise!" I did not wish to disobey

my father. I did not

want to disoblige my friends. Suzanne loosed her red scarf and

tossed one

end to me. I caught the end of the shawl that Suzanne was already

waving

over her head and began the first steps, but it took me only an

instant to

see that the task was beyond my powers. I grew confused, my head

swam, and

I stopped. But Alix did not stop playing; and Suzanne, wrapped in

her

shawl and turning upon herself, cried, "Play on!"

I understood her intention in an instant.

Harp and flute sounded on, and Suzanne, ever gliding, waltzing,

leaping,

her arms gracefully lifted above her head, softly waved her scarf,

giving

it a thousand different forms. Thus she made, twice, the circuit

of the

deck, and at length paused before Mario Carlo. But only for a

moment. With

a movement as quick as unexpected, she threw the end of her scarf

to him.

It wound about his neck. The Italian with a shoulder movement

loosed the

scarf, caught it in his left hand, threw his violin to Celeste,

and bowed

low to his challenger. All this as the etiquette of the bolero

inexorably

demanded. Then Maestro Mario smote the deck sharply with his

heels, let go

a cry like an Indian's war-whoop, and made two leaps into the air,

smiting

his heels against each other. He came down on the points of his

toes,

waving the scarf from his left hand; and twining his right arm

about my

sister's waist, he swept her away with him. They danced for at

least half

an hour, running the one after the other, waltzing, tripping,

turning,

leaping. The children and Gordon shouted with delight, while my

father, M.

Carpentier, and even Alix clapped their hands, crying, "Hurrah!"

Suzanne's want of dignity exasperated me; but when I tried to

speak of it,

papa and Alix were against me.

"On board a flatboat," said my father, "a breach of form is

permissible."

He resumed his flute with the first measures of a minuet.

"Ah, our turn!" cried Alix; "our turn, Françoise! I will

be the cavalier!"

I could dance the minuet as well as I could the bolero — that is,

not at

all; but Alix promised to guide me: and as, after all, I loved the

dance

as we love it at sixteen, I was easily persuaded, and fan in hand

followed

Alix, who for the emergency wore her husband's hat; and our minuet

was

received with as much enthusiasm as Suzanne's bolero. This ball

was

followed by others, and Alix gave me many lessons in the dance,

that some

weeks later were very valuable in the wilderness towards which we

were

journeying.

VIII.

A BAD STORM IN A BAD PLACE.

The flatboat continued its course, and some slight signs of

civilization

began to appear at long intervals. Towards the end of a beautiful

day in

June, six weeks after our departure from New Orleans, the flatboat

stopped

at the pass of

Lake Chicot.

The sun was setting in a belt of

gray

clouds. Our men fastened their vessel securely and then cast their

eyes

about them.

"Ah!" cried Mario, "I do not like this place; it is inhabited."

He pointed

to a wretched hut half hidden by the forest. Except two or three

little

cabins seen in the distance, this was

the first habitation

that

had met

our eyes since leaving the Mississippi.

A woman showed herself at the door. She was scarcely dressed at

all. Her

feet were naked, and her tousled hair escaped from a wretched

handkerchief

that she had thrown upon her head. Hidden in the bushes and behind

the

trees half a dozen half-nude children gazed at us, ready to fly at

the

slightest sound. Suddenly two men with guns came out of the woods,

but at

the sight of the flatboat stood petrified. Mario shook his head.

"If it were not so late I would take the boat farther on."

[Yet he went hunting with 'Tino and Gordon along the shore,

leaving the

father of Françoise and Suzanne lying on the deck with sick

headache,

Joseph fishing in the flatboat's little skiff, and the women and

children

on the bank, gazed at from a little distance by the sitting

figures of the

two strange men and the woman. Then the hunters returned, supper

was

prepared, and both messes ate on shore. Gordon and Mario joining

freely in

the conversation of the more cultivated group, and making

altogether a

strange Babel of English, French, Spanish, and Italian.]

After supper Joseph and Alix, followed by my sister and me,

plunged into

the denser part of the woods.

"Take care, comrade," we heard Mario say; "don't go far."

The last rays of the sun were in the treetops. There were flowers

everywhere. Alix ran here and there, all enthusiasm. Presently

Suzanne

uttered a cry and recoiled with affright from a thicket of

blackberries.

In an instant Joseph was at her side; but she laughed aloud,

returned to

the assault, and drew by force from the bushes a little girl of

three or

four years. The child fought and cried; but Suzanne held on, drew

her to

the trunk of a tree, sat down, and held her on her lap by force.

The poor

little thing was horribly dirty, but under its rags there were

pretty

features and a sweetness that inspired pity. Alix sat down by my

sister

and stroked the child's hair, and, like Suzanne, spite of the

dirt, kissed

her several times; but the little creature still fought, and

yelled [in

English]:

"Let me alone! I want to go home! I want to go home!"

Joseph advised my sister to let the child go, and Suzanne was

about to do

so when she remembered having at supper filled her pocket with

pecans. She

quickly filled the child's hands with them and the Rubicon was

passed. . . .

She said that her name was Annie; that her father, mother, and

brothers

lived in the hut. That was all she could say. She did not know her

parents' name. When Suzanne put her down she ran with all her legs

towards

the cabin to show Alix's gift, her pretty ribbon.

Before the sun went down the wind rose. Great clouds covered the

horizon;

large rain-drops began to fall. Joseph covered the head of his

young wife

with her mantle, and we hastened back to the camp.

"Do you fear a storm, Joseph?" asked Alix.

"I do not know too much," he replied; "but when you are near, all

dangers

seem great."

We found the camp deserted; all our companions were on board the

flatboat.

The wind rose to fury, and now the rain fell in torrents. We

descended to

our rooms. Papa was asleep. We did not disturb him, though we were

greatly

frightened. . . . Joseph and Gordon went below to sleep. Mario and

his son

loosed the three bull-dogs, but first removed the planks that

joined the

boat to the shore. Then he hoisted a great lantern upon a mast in

the bow,

lighted his pipe, and sat down to keep his son awake with stories

of

voyages and hunts.

The storm seemed to increase in violence every minute. The rain

redoubled

its fury. Frightful thunders echoed each other's roars. The

flatboat,

tossed by the wind and waves, seemed to writhe in agony, while now

and

then the trunks of uprooted trees, lifted by the waves, smote it

as they

passed. Without a thought of the people in the hut, I made every

effort to

keep awake in the face of these menaces of Nature. Suzanne held my

hand

tightly in hers, and several times spoke to me in a low voice,

fearing to

wake papa, whom we could hear breathing regularly, sleeping

without a

suspicion of the surrounding dangers. Yet an hour had not passed

ere I was

sleeping profoundly. A knock on the partition awoke us and made us

run to

the door. Mario was waiting there.

"Quick, monsieur! Get the young ladies ready. The flatboat has

probably

but ten minutes to live. We must take the women and children

ashore. And

please, signorina," — to my sister, — "call M. and Mme. Carpentier."

But

Joseph had heard all, and showed himself at the door of our room.

"Ashore? At such a time?"

"We have no choice. We must go or perish."

"But where?"

"To the hut. We have no time to talk. My family is ready". . . .

It took but a few minutes to obey papa's orders. We were already

nearly

dressed; and as sabots were worn at that time to protect the shoes

from

the mud and wet, we had them on in a moment. A thick shawl and a

woolen

hood completed our outfits. Alix was ready in a few moments.

"Save your jewels, — those you prize most, — my love," cried

Carpentier,

"while I dress."

Alix ran to her dressing-case, threw its combs, brushes, etc.,

pell-mell

into the bureau, opened a lower part of the case and took out four

or five

jewel-boxes that glided into her pockets, and two lockets that she

hid

carefully in her corsage. Joseph always kept their little fortune

in a

leathern belt beneath his shirt. He put on his vest and over it a

sort of

great-coat, slung his gun by its shoulder-belt, secured his

pistols, and

then taking from one of his trunks a large woolen cloak he wrapped

Alix in

it, and lifted her like a child of eight, while she crossed her

little

arms about his neck and rested her head on his bosom. Then he

followed us

into Mario's room, where his two associates were waiting. At

another time

we might have laughed at Maggie, but not now. She had slipped into

her

belt two horse-pistols. In one hand she held in leash her bull-dog

Tom,

and in the other a short carbine, her own property.

IX.

MAGGIE AND THE ROBBERS.

"We are going out of here together," said Mario; "but John and I

will

conduct you only to the door of the hut. Thence we shall return to

the

flatboat, and all that two men can do to save our fortune shall be

done.

You, monsieur, have enough to do to take care of your daughters.

To you,

M. Carpentier — to you, son Celestino, I give the care of these

women and

children."

"I can take care of myself," said Maggie.

"You are four, well armed," continued Mario. (My father had his

gun and

pistols.) "This dog is worth two men. You have no risks to run;

the

danger, if there be any, will be with the boat. Seeing us divided,

they

may venture an attack; but one of you stand by the window that

faces the

shore. If one of those men in the hut leaves it, or shows a wish

to do so,

fire one pistol-shot out of the window, and we shall be ready for

them;

but if you are attacked, fire two shots and we will come. Now,

forward!"

We went slowly and cautiously: 'Tino first, with a lantern; then

the Irish

pair and child; then Mario, leading his two younger boys, and

Celeste,

with her daughter asleep in her arms; and for rear-guard papa with

one of

us on each arm, and Joseph with his precious burden. The wind and

the

irregularities of the ground made us stumble at every step. The

rain

lashed us in the face and extorted from time to time sad

lamentations from

the children. But, for all that, we were in a few minutes at the

door of

the hovel.

"M. Carpentier," said Mario, "I give my family into your care."

Joseph

made no answer but to give his hand to the Italian. Mario strode

away,

followed by Gordon.

"Knock on the door," said Joseph to 'Tino. The boy knocked. No

sound was

heard inside, except the growl of a dog.

"Knock again." The same silence. "We can't stay here in this

beating

rain; open and enter," cried Carpentier. 'Tino threw wide the door

and we

walked in.

There was but one room. A large fire burned in a clay chimney

that almost

filled one side of the cabin. In one corner four or five chickens

showed

their heads. In another, the woman was lying on a wretched pallet

in all

her clothes. By her slept the little creature Suzanne had found,

her

ribbon still on her frock. Near one wall was a big chest on which

another

child was sleeping. A rough table was in the middle, on it some

dirty tin

plates and cups, and under it half a dozen dogs and two little

boys. I

never saw anything else like it. On the hearth stood the pot and

skillet,

still half full of hominy and meat.

Kneeling by the fire was a young man molding bullets and passing

them to

his father, seated on a stool at a corner of the chimney, who

threw them

into a jar of water, taking them out again to even them with the

handle of

a knife. I see it still as if it was before my eyes.

The woman opened her eyes, but did not stir. The dogs rose

tumultuously,

but Tom showed his teeth and growled, and they went back under the

table.

The young man rose upon one knee, he and his father gazing

stupidly at us,

the firelight in their faces. We women shrank against our

protectors,

except Maggie, who let go a strong oath. The younger man was

frightfully

ugly; pale-faced, large-eyed, haggard, his long, tangled, blonde

hair on

his shoulders. The father's face was written all over with

depravity and

crime. Joseph advanced and spoke to him.

"What the devil of a language is that?" he asked of his son in

English.

"He is asking you," said Maggie, "to let us stay here till the

storm is

over."

"And where do you come from this way?"

"From that flatboat tied to the bank."

"Well, the house isn't big nor pretty, but you are its masters."

Maggie went and sat by the window, ready to give the signal. Pat

sank at

her feet, and laying his head upon Tom went straight to sleep.

Papa sat

down by the fire on an inverted box and took me on one knee. With

her head

against his other, Suzanne crouched upon the floor. We were

silent, our

hearts beating hard, wishing ourselves with mamma in St. James.

Joseph set

Alix upon a stool beside him and removed her wrapping.

"Hello!" said the younger stranger, "I thought you were carrying

a child.

It's a woman!"

An hour passed. The woman in the corner seemed to sleep; Celeste,

too,

slumbered. When I asked Suzanne, softly, if she was asleep, she

would

silently shake her head. The men went on with their task, not

speaking. At

last they finished, divided the balls between them, put them into

a

leather pouch at their belt, and the father, rising, said:

"Let us go. It is time."

Maggie raised her head. The elder man went and got his gun and

loaded it

with two balls, and while the younger was muffling himself in an

old

blanket-overcoat such as we give to plantation negroes, moved

towards the

door and was about to pass out. But quicker than lightning Maggie

had

raised the window, snatched a pistol from her belt, and fired. The

two men

stood rooted, the elder frowning at Maggie. Tom rose and showed

two rows

of teeth.

"What did you fire that pistol for? What signal are you giving?"

"That is understood at the flatboat," said Maggie, tranquilly. "I

was to

fire if you left the house. You started, I fired, and that's all."

" — — ! And did you know, by yourself, what we were going to do?"

"I haven't a doubt. You were simply going to attack and rob the

flatboat."

A second oath, fiercer than the first, escaped the man's lips.

"You talk

that way to me! Do you forget that you're in my power?"

"Ah! Do you think so?" cried Maggie, resting her fists on her

hips. "Ah,

ha, ha!" That was the first time I ever heard her laugh — and such a

laugh!

"Don't you know, my dear sir, that at one turn of my hand this dog

will

strangle you like a chicken? Don't you see four of us here armed

to the

teeth, and at another signal our comrades yonder ready to join us

in an

instant? And besides, this minute they are rolling a little cannon

up to

the bow of the boat. Go, meddle with them, you'll see." She lied,

but her

lie averted the attack. She quietly sat down again and paid the

scoundrel

not the least attention.

"And that's the way you pay us for taking you in, is it? Accuse a

man of

crime because he steps out of his own house to look at the

weather? Well,

that's all right." While the man spoke he put his gun into a

corner,

resumed his seat, and lighted a cob pipe. The son had leaned on

his gun

during the colloquy. Now he put it aside and lay down upon the

floor to

sleep. The awakened children slept. Maggie sat and smoked. My

father,

Joseph, and 'Tino talked in low tones. All at once the old ruffian

took

his pipe from his mouth and turned to my father.

"Where do you come from?"

"From New Orleans, sir."

"How long have you been on the way?"

"About a month."

"And where are you going," etc. Joseph, like papa, remained

awake, but

like him, like all of us, longed with all his soul for the end of

that

night of horror.

At the first crowing of the cock the denizens of the hut were

astir. The

father and son took their guns and went into the forest. The fire

was

relighted. The woman washed some hominy in a pail and seemed to

have

forgotten our presence; but the little girl recognized Alix, who

took from

her own neck a bright silk handkerchief and tied it over the

child's head,

put a dollar in her hand, and kissed her forehead. Then it was

Suzanne's

turn. She covered her with kisses. The little one laughed, and

showed the

turban and the silver that "the pretty lady," she said, had given

her.

Next, my sister dropped, one by one, upon the pallet ten dollars,

amazing

the child with these playthings; and then she took off her red

belt and

put it about her little pet's neck.

My father handed me a handful of silver. "They are very poor, my

daughter;

pay them well for their hospitality." As I approached the woman I

heard

Joseph thank her and offer her money.

"What do you want me to do with that?" she said, pushing my hand

away.

"Instead of that, send me some coffee and tobacco."

That ended it; I could not pay in money. But when I looked at the

poor

woman's dress so ragged and torn, I took off [J'autai] my shawl,

which was

large and warm, and put it on her shoulders, — I had another in the

boat, — and she was well content. When I got back to the flatboat I

sent

her some chemises, petticoats, stockings, and a pair of shoes. The

shoes

were papa's. Alix also sent her three skirts and two chemises, and

Suzanne