chapter two.

LAFITTE, “THE PIRATE.”

About one mile above New Orleans, opposite the flourishing City of Jefferson and on the right bank of the Mississippi, there is a small canal now used by fishermen and hunters, which approaches within a few hundred yards of the river’s bank, wrote Judge Walker, who gives remarkable pen pictures of Lafitte, “the pirate” and Lafitte, “the patriot.”

Following this canal (now Harvey’s) which runs nearly due south for five or six miles, we reach a deep, narrow and tortuous bayou (Little Barataria). Descending this and another bayou (Big Barataria), which for thirty miles threads its sluggish course through an impenetrable swamp, we pass into Little Lake, once girted with sombre forests and gloomy swamps and resonant with the hoarse croaking of alligators, and the screams of swamp fowls.

From this lake we pass into another lake, and from that into Barataria Bay, until we reach an island on which are discernible, at a considerable distance, several elevated knolls, and where a scant vegetation and a few trees maintain a feeble existence. At the lower end of this island there are some curious aboriginal vestiges in the shape of high mounds of shells which are thought to mark the burial of some extinct, tribes. This surmise has been confirmed by the discovery of human bones below the surface of these mounds. The elevation formed by the series of mounds is known as the Temple, from a tradition that the Natchez Indians used to assemble there to offer sacrifices to their chief diety, the “Great Sun.” This lake or bayou finally disembogues into the Gulf of Mexico by two outlets, between which lies the beautiful island of Grand Terre with a length of six miles and an average breadth of a mile and a half.

At the western extremity of the island at the present time stands what was once a large and powerful fortification, which was erected by the United States and named after one of the most distinguished benefactors of Louisiana, Edward Livingston. This fort commanded the western entrance or strait leading from the Gulf into the lake or bay of Barataria, but it has now fallen into decay and ruin.

Here may be found, even now, the foundations of houses, the brickwork of a rude fort, and other evidences of an ancient settlement. This ig the spot which has become so famous in the history and romances of the Southwest, as the “Pirate’s Home,” the retreat of the dead Corsair of the Gulf, whom the genius of Byron, and of many succeeding poets and novelists, has consecrated as one who

“Left a corsair’s name to other times,

Linked with one virtue and a thousand crimes.”

Such is poetry — such is romance. But authentic history, by which alone Judge Walker was guided, dissipates all these fine flights of the poet and romancer.

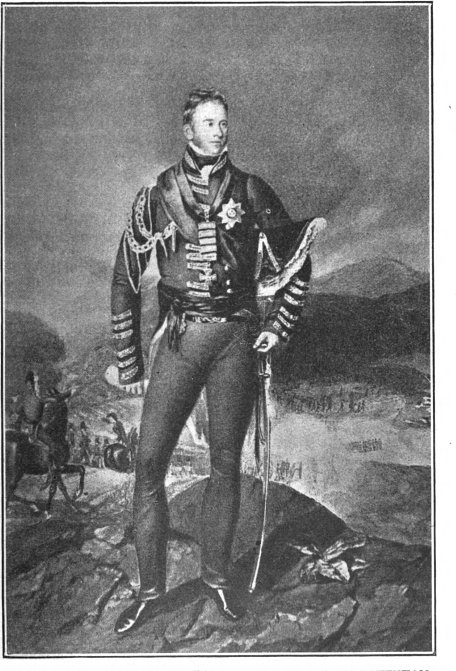

“Shortly after the cession of Louisiana to the United States in 1803, a series of events occurred which made the Gulf of Mexico the arena of the most extensive and profitable privateering,” runs Walker’s narrative. “First came the war between France and Spain, which afforded the inhabitants of the French islands a good pretence to depredate upon the rich commerce of the Spanish possessions — the most valuable and productive in the New World. The Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea swarmed with privateers, owned and employed by men of all nations, who obtained their commissions (by purchase) from the French authorities at Martinique and Guadelupe. Among these were not a few neat trim crafts belonging to the staid citizens of New England who, under the tri-color of France, experienced no scruples in the perpetrating of acts which, though not condemned by the laws of nations, in their spirit as well as in their practical results, bore a strong resemblance in piracy. The British capture and occupation of Guadalupe and Martinique, in 1806, in which expeditions the then Col. Edward Pakenham, who will figure more conspicuously in Louisiana history later on in this series of sketches, distinguished himself and received a severe wound, broke up a favorite retreat of these privateers.

“Shortly after this Colombia declared her independence of Spain and invited to her port of Carthagena the patriots and adventurers of all nations to aid her struggle against the mother country. Thither flocked all the privateers and buccaneers of the Gulf. Commissions were promptly given or sold to them to sail under the Colombian flag and to prey upon the commerce of poor old Spain who, invaded and despoiled at home, had neither means nor spirit to defend her distant possessions.

“The success of the privateers was brilliant. It is a narrow line, at the best, which divides piracy from privateering, and it is not at all wonderful that the reckless sailors of the Gulf sometimes lost sight of it. The shipping of other countries was, no doubt, frequently mistaken for that of Spain. Rapid fortunes were made in this business. Capitalists embarked their means in equipping vessels for privateering. Of course, they were not responsible for the excesses which were committed by those in their employ, nor did they trouble themselves to inquire into all the acts of their agerts. Finally, however, some attention was excited by this wholesale system of legalized pillage. The privateers found it necessary to secure some safe harbor into which they could escape from the ships of war, where they could be sheltered from the northers, and where, too, they could establish a depot for the sale and smuggling of their spoils. It was a sagacious thought which selected the little bay or cove of Grand Terre for this purpose. It was called Barataria and several huts and storehouses were built there and cannon planted on the beach. Here rallied the privateers of the Gulf with their fast-sailing schooners, armed to the teeth and manned by fierce-looking men who wore sharp cutlasses and might be taken anywhere for pirates, without offense. They were the desperate men of all nations, embracing as well those who had occupied respectable positions in the naval or merchant service, who were instigated to their present pursuit by the love of gain, as those who figured in the bloody scenes of the buccaneers of the Spanish Main. Besides its inaccessibility to vessels of war, the Bay of Barataria recommended itself by another important consideration: it was near to the City of New Orleans, the. mart of the growing valley of the Mississippi and from it the lakes and bayous afforded an easy water communication, nearly to the banks of the Mississippi, within a short distance of the city. A regular organization of the privateers was established, officers were chosen, and agents appointed in New Orleans to enlist men and negotiate the sale of goods.”

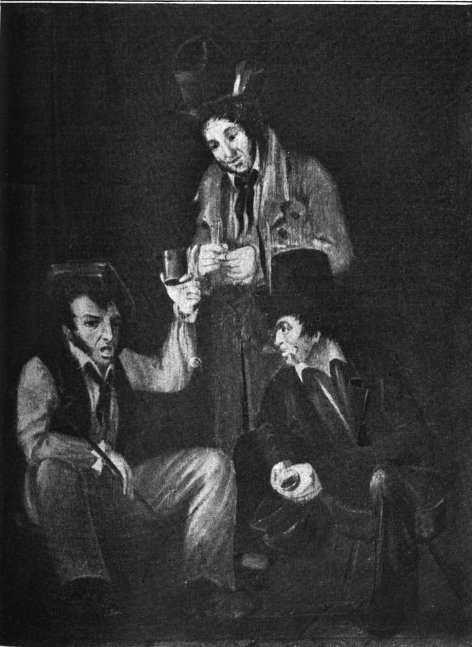

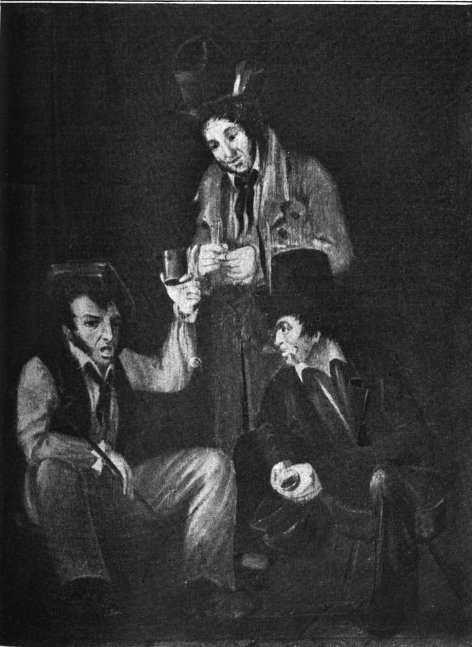

“Chief among these ‘agents’ were Jean and Pierre Lafitte. Jean, the younger, but more conspicuous of the two, was a handsome man, fair, with black hair and eyes, wearing his beard, as the fashion was, shaven neatly away from the front of his face. His manner was generally courteous, though he was irascible and in graver moments somewhat harsh. He spoke fluently English, Spanish, Italian and French, using them with much affability at the hotel where he resided and indicating, in the peculiarities of his French, his nativity in the city of Bordeaux,” says George W. Cable, who, in his exhaustive study of Louisiana, naturally devoted considerable attention to this world-famous figure.

“The elder brother was a seafaring man and had served in the French navy. He appears to have been every way less showy than the other; but beyond doubt both men were above the occupation with which they began life in Louisiana. This was the trade of blacksmith, though at their forge, on the corner of St. Philip and Bourbon Streets, probably none but slave hands swung the sledge or shaped the horseshoe.

“The Mississippi’s ‘coasts’ in the Parishes of St. James and St. John the Baptist were often astir with Jean Lafitte’s known presence, and his smaller vessels sometimes pierced the interior as far as Lac des Allemands. He knew the value of popular admiration, and was often at country balls, where he enjoyed the fame of great riches and courage, and seduced many of the simple Acadian youth to sail in his cruises. His two principal captains were Beluche and Dominique You. ‘Captain Dominique,’ was small, graceful, fair, of a pleasant, even attractive face, and a skillful sailor. There were also Gambio, a handsome Italian, who died in the late ’70s at the old private village of Cheniere Caminada; and Rigaud, a dark Frenchman, whose ancient house still stands on Grand Isle. And yet again Johanness and Jahannot, unless — which appears likely — these were only the real names of Dominique You and Beluche.”

“Therefore, the most active and sagacious of these town agents, was the ‘blacksmith’ of St. Philip Street who, following the example of much greater and more pretentious men, abandoned his sledge and anvil and embarked in the lawless and more adventurous career of smuggling and privateering,” continues Judge Walker. “Gradually, by his success, enterprise and address, Jean Lafitte obtained such ascendancy over the lawless congregation at Barataria, that they elected him their Captain or Commodore.

“There is a tradition that this choice gave great dissatisfaction to some of the more warlike of the privateers,” continues Walker, “and particularly to Gambio, a savage, grim Italian, who did not scruple to prefer the title and character of ‘pirate,’ to the puling, hypocritical one of ‘privateer.’ But it is said, the story is verified by an aged Italian, one of the only two survivors of the Baratarians, resident in Grand Terre (in Walker’s time) who rejoiced in the

nom de guerre,

indicative of a ghastly sabre cut across the face, of

Nez Coupe,

that Lafitte found it necessary to sustain his authority by some terrible example and when one of Gambio’s follower’s resisted his orders, he shot him through the heart before the whole band. Whether this story be true or not, there can be no doubt that in the year 1813, when the association had attained its greatest prosperity, Lafitte held undisputed authority and control over it. He certainly conducted his administration with energy and ability. A large fleet of small vessels rode in the harbor besides others that were cruising. Their store-houses were filled with valuable goods. Hither resorted merchants and traders from all parts of the country to purchase goods which, being cheaply obtained, could be retailed at a large profit. A number of small vessels were employed in transporting goods to New Orleans through the bayou described, just as oysters, fish and game are now brought.

“On reaching the head of the bayou, these goods would be taken out of the boats and placed on the backs of mules — to be carried to the river banks — whence they would be ferried across into the city, at night. In the city they had many agents who disposed of these goods. By this profitable trade several citizens of New Orleans laid the foundations of their fortunes. But though profitable to individuals this trade was evidently detrimental to regular and legitimate commerce as well as to the revenue of the Federal Government. Accordingly, several efforts were made to break up the association but the activity and influence of their city friends generally enabled them to hush up such designs.

“Legal prosecutions were commenced on April 7, 1813, against Jean and Pierre Lafitte, in the United States District Court for Louisiana, charging them with violating the Revenue and Neutrality Laws of the United States. Nothing is said about piracy — the gravest offence charged being simply a misdemeanor. Even these charges were not sustained for, although both the Lafittes, and many others of the Baratarians were captured by Captain Andrew Holmes, in an expedition down the bayou, about the time of the filing of these informations against them, yet it appears they were released and the prosecutions never came to trial, the warrants for their arrest being returned ‘not found.’

“However, in 1814 indictments for piracy were found against several of the Baratarians. One against Johnness, for piracy on the Santa, a Spanish vessel, which was capturned nine miles from Grand Isle and nine thousand dollars taken from her; also against another who went by the name of Johannot, for capturing another Spanish vessel with her cargo, worth thirty thousand dollars, off Trinidad. Pierre Lafitte was charged as aider and abettor in these crimes before and after the fact, as one who did ‘upon land, to-wit: in the City of New Orleans, within the District of Louisiana, knowingly and willingly aid, assist, procure, counsel and advise the said piracies and robberies.’ It is quite evident from the character of the ships captured, that had the indictments been prosecuted to a trial, they would have resulted in modifying the crime of piracy into the offence of privateering, or that of violating Neutrality Laws of the United States, by bringing prizes taken from Spain into its territory and selling the same.

“Pierre Lafitte was arrested on these indictments. An application for bail was refused, and he was incarcerated in the Calaboose, or city prison, the cells of which now surround the courtyard of the Cabildo. These transactions, betokening a vigorous determination on the part of the authorities to break up the establishment at Barataria, Jean Lafitte proceeded to that place and was engaged in collecting the vessels and property of the association, with a view of departing to some more secure retreat, when an event occurred which he thought would afford him an opportunity of propitiating the favor of the government and securing for himself and his companions a pardon for their offences.

“It was on the morning of the third of September, 1814, that the settlement of Barataria was aroused by the report of cannon in the direction of the Gulf. Lafitte immediately ordered out a small boat in which, rowed, by four of his men, he proceeded toward the mouth of the strait. Here he perceived a brig of war, lying just outside of the inlet, with the British colors flying at the masthead. As soon as Lafitte’s boat was perceived, the gig of the brig shot off from her side and approached him.

“In this gig were officers, one clad in naval uniform, and one in the scarlet of the British army. They bore a white signal in the bows and a British flag in the stern of their boat. The officers proved to be Captain Lockyer, of his Majesty’s navy, with a lieutenant of the same service, and Captain McWilliams of the army. On approaching the boat of the Baratarians Captain Lockyer called out his name and rank, and inquired if Mr. Lafitte was at home in the bay as he had an important communication for him. Lafittee replied that the person they desired could be seen ashore and invited the officers to accompany him to their settlement. They accepted the invitation and the boats were rowed through the strait into the Bay of Barataria. On their way Lafitte confessed his true name and character; whereupon Captain Lockyer delivered to him a paper package. Lafitte enjoined upon the British officers to conceal the true object of their visit from his men who might, if they suspected their design, attempt some violence against them. Despite these cautions the Baratarians, on recognizing the uniform of the strangers, collected on the shore in a tumultuous and threatening manner and clamored loudly for their arrest. It required all Lafitte’s art, address, and influence to calm them. Finally, however, he succeeded in conducting the British to his apartments where they were entertained in a style of elegant hospitality which greatly surprised them.

“The best wines of old Spain, the richest fruits of the West Indies and every variety of fish and game were spread out before them and served on the richest carved silver plate. The affable manner of Lafitte gave great zest to the enjoyment of his guests. After the repast, when they had all smoked cigars of the finest Cuban flavor, Lafitte requested his guests to proceed to business.”

The package directed to “Mr. Lafitte,” was then opened and the contents read. They consisted of a proclamation, signed by Col. Edward Nicholls, commander of the British land forces on the coast of Florida, which read:

PROCLAMATION.

By Lieutenant-Colonel Edward Nicholls, commanding his Britannic Majesty’s forces in the Floridas.

Native of Louisiana! on you the first call is made to assist in liberating from a faithless imbicile government, your paternal soil: Spaniards, Frenchmen, Italians and British whether settled or residing for a time in Louisiana, on you also I call to aid me in this just cause: the American usurpation in this country must be abolished and the lawful owners of the soil put in possession. I am at the head of a large body of Indians, well armed disciplined and commanded by British officers — a good train of artillery with every requisite, seconded by the powerful aid of a numerous British and Spanish squadron of ships and vessels of war. Be not alarmed, inhabitants of the country at our approach; the same good faith and disinterestedness which has distinguished the conduct of Britons in Europe, accompanies them here; you will have no fear of litigious taxes imposed on you for the purpose of carrying on an unnatural and unjust war; your property, your laws, the peace and tranquility of your country, will be guaranteed to you by men who will suffer no infringement of theirs; rest assured that these brave red men only burn with an ardent desire of satisfaction for their wrongs they have suffered from the Americans, to join you in liberating these southern provinces from their yoke and drive them into those limits formerly prescribed by my sovereign. The Indians have pledged themselves in the most solemn manner not to injure in the slightest degree the persons or properties of any but enemies to their Spanish or English fathers; a flag over any door whether Spanish, French or British will be a certain protection, nor dare any Indian put his foot on the threshold thereof, under the penalty of death from his own countrymen; not even an enemy will an Indian put to death, except resisting in arms, and as for injuring helpless women and children, the red men by their good conduct and treatment to them (if it be possible) make the Americans blush for their more inhuman conduct lately on the Escambia, and within a neutral territory.

Inhabitants of Kentucky, you have too long borne with grievous impositions — the whole brunt of the war has fallen on your brave sons; be imposed on no longer, but either range yourselves under the standard of your forefathers, or observe a strict neutrality; if you comply with either of these offers, whatever provisions you send down will be paid for in dollars and the safety of the persons bringing it as well as the free navigation of the Mississippi guaranteed to you.

Men of Kentucky, let me call to your view (and I trust to your abhorence) the conduct of those factions which hurried you into this civil, unjust and unnatural war at the time when Great Britain was straining every nerve in defence of her own and the liberties of the world — when the bravest of her sons were fighting and bleeding in so sacred a cause — when she was spending millions of her treasure in endeavoring to pull down one of the most formidable and dangerous tyrants that ever disgraced the form of man — when groaning Europe was almost in her last gasp — when Britons alone showed an undaunted front — basely did those assassins endeavor to stab her from the rear; she was turned on them renovated from the bloody but successful struggle — Europe is happy and free, and she now hastens justly to avenge the unprovoked insult. Show them that you are not collectively unjust; leave that contemptible few to shift for themselves let those slaves of the tyrant send an embassy to Elba, and implore his aid, but let every honest, upright American spurn them with united contempt. After the experience of twenty-one years, can you anv longer support those brawlers for liberty who call it freedom when themselves are free; be no longer their dupes — accept of my offers — everything I have promised in this paper I guarantee to you on the sacred honour of a British officer.

Given under my hand at my head-quarters, Pensacola, this 29th day of August, 1814.

Edward Nicholls.

The second communication was from the same writer to “Mr. Lafitte, or commandant at Barataria,” which frankly bid for the pirate’s services in the British navy, for which rewards would be given not only the leader but his men. It read:

Headquarters, Pensacola, August 31st, 1814.

Sir:

I have arrived in the Floridas for the purpose of annoying the only enemy Great Britain has in the world, as France and England are now friends. I call on you with your brave followers to enter into the service of Great Britain in which you shall have the rank of a Captain; lands will be given to you all in proportion to your respective ranks on a peace taking place, and I invite you on the following terms:

Your property shall be guaranteed to you and your persons protected; in return for which I ask you to cease all hostilities against Spain or the allies of Great Britain. — Your ships and vessels to be placed under the orders of the commanding officer on this station, until the commander-in-chief’s pleasure is known, but I guarantee their fair value at all events. I herewith enclose you a copy of my proclamation to the inhabitants of Louisiana, which will, I trust point out to you the honourable intentions of my government. You may be an useful assistant to me, in forwarding them; therefore, if you determine, lose no time. The bearer of this, Captain M’Williams will satisfy you on any other point you may be anxious to learn as will Captain Lockyer of the Sophia, who brings him to you. We have a powerful re-enforcement on its. way here, and I hope to cut out some other work for the Americans than oppressing the inhabitants of Louisiana. Be expeditious in your resolves and rely on the verity of

Your very humble servant,

Edward Nicholls.

The third letter was from the Hon. William Henry Percy, captain of His Majesty’s ship Hermes and senior officer in the Gulf of Mexico, to Nicholas Lockyer, Esq., commander of H. M. Sloop Sophia:

Sir:

You are hereby required and directed after having received on board an officer belonging to the first battalion of Royal colonial marines to proceed, in His Majesty’s sloop under your command, without a moment’s loss of time for Barataria.

On your arrival at that place you will communicate with the chief persons there — you will urge them to throw themselves under the protection of Great Britain — and, should you find them inclined to pursue such a step, you will hold out to them that their property shall be secured to them, that they shall be considered British subjects and at the conclusion of the war, lands within his majesty’s colonies in America will be allotted to them in return for these concessions. You will insist on an immediate cessation of hostilities against Spain, and in case they should have any Spanish property not disposed of that it be restored and that they put their naval force into the hands of the senior officer here until the commander-in-chief’s pleasure is known. In the event of their not being inclined to act offensively against the United States you will dp all in your power to persuade them to a strict neutrality, and still endeavor to put a stop in their hostilities against Spain. Should you succeed completely in the object for which you are sent, you will concert such measures for the annoyance of the enemy as you judge best from circumstances; having an eye to the junction of their small armed vessels with me for the capture of Mobile, &c.

You will at all events yourself join me with the utmost despatch at this post with the accounts of your success.

Given under my hand on board his majesty’s ship Hermes, at Pensacola, this 30th day of August, 1814.

W. H. Percy, capt.

The fourth letter carried a more direct threat and was dated two days later:

Having understood that some British merchantmen have been detained, taken into and sold by the inhabitants of Barataria, I have directed Captain Lockyer of his majesty’s sloop Sophia to proceed to that place and inquire into the circumstances with positive orders to demand instant restitution, and in case of refusal to destroy to his utmost every vessel there as well as to carry destruction over the whole place and at the same time to assure him of the co-operation of all his majesty’s naval forces on this station. I trust at the same time that the inhabitants of Barataria consulting their own interest, will not make it necessary to proceed to such extermities — I hold out at the same time a war instantly destructive to them; and on the other hand should they be inclined to assist Great Britain in her just and unprovoked war against the United States, the security of their property, the blessings of the British constitution — and should they be inclined to settle on this continent, lands will at the conclusion of the war be allotted to them in his majesty’s colonies in America. In return for all these concessions on the part of Great Britain, I expect that the directions of their armed vessels will be put into my hands (for which they will be remunerated), the instant cessation of hostilities against the Spanish government, and the restitution of any undisposed property of that nation.

Should any inhabitants be inclined to volunteer their services into his majesty’s forces either naval or military for limited services, they will be received; and if any British subject being at Barataria wishes to return to his native country, he will, on joining his majesty’s service, receive a free pardon.

Given under my hand on board H. M. ship Hermes,

Pensacola, this 1st. day of September, 1814.

W. H. Percy,

Captain and Senior Officer.

These letters were once part of the records of the United States District Court in New Orleans, where they were filed by Lafitte’s lawyers, Edward Livingston and John R. Grimes, as documentary evidence for the Lafittes when they were arrested for piracy some years after the war was over and the Battle of New Orleans won. From the archives of the court they disappeared, but turned up years after in a curio store where they were purchased by Mr. S. J. Schwartz, of New Orleans, in whose possession they are today.

“Besides the flattering offers the letters contained, the British officers proceeded to enlarge upon them by many plausible and cogent arguments,” Walker writes. “Captain McWilliams stated that Lafitte, his vessels and men would be enlisted in the honorable service of the British navy; that he would then receive the rank of Captain (an offer which must have brought a smile to the face of the unnautical blacksmith of St. Philip Street) and the sum of thirty thousand dollars: that being a Frenchman, proscribed and persecuted by the United States, with a brother then in prison, he should unite with the English, as the English and French were now fast friends; that a splendid prospect was now opened to him in the British navy, as from his knowledge of the Gulf Coast he could guide them in their expedition to New Orleans, which had already started; that it was the purpose of the English Government to penetrate the upper country and act in concert with the forces in Canada; that everything was prepared to carry on the war with unusual vigor; that they were sure of success, expecting to find little or no opposition from the French and Spanish population of Louisiana whose interests and manners were opposed and hostile to those of the Americans; and, finally, it was declared by Captain Lockyer to be the purpose of the British to free the slaves and arm them against the white people who resisted their authority and progress.

“Lafitte, effecting an acquiescence in the proposition, begged to be permitted to go and consult an old friend and associate in whose judgment he had great confidence. Whilst he was absent his men, who had watched suspiciously the conference, many of whom were Americans and none the less patriotic because they had a taste for privateering, proceeded to arrest the British officers, threatening to kill or deliver them up to the Americans. In the midst of this clamor and violence, Lafitte returned and immediately quieted his men by reminding them of the laws of honor and humanity which forbade any violence to persons who come among them with a flag of truce. He assured them that their honor and rights would be safe arid sacred in his charge. He then escorted the British to their boats and, after declaring to Captain Lockyer that he only required a few days to consider the flattering proposals and would be ready at a certain time to deliver his final reply, took a respectful leave of his guests, kept them in v1ew until they were out of reach of the men on shore.”

Immediately after the departure of the British, Lafitte sat down and addressed a long letter to John Blanque, a member of the House of Representatives of Louisiana, which read:

Barataria, 4th September, 1814.

Sir,

Though proscribed by my adopted country, I will never let slip any occasion of serving her or of proving that she has never ceased to be dear to me. Of this you will here see a convincing proof. Yesterday, the 3d of September, there appeared here, under a flag of truce, a boat coming from an English brig, at anchor about two leagues from the pass. Mr. Nicholas Lockyer, a British officer of high rank, delivered me the following papers: two directed to me, a proclamation, and the admiral’s instructions to that officer, all herewith enclosed. You will see from their contents the advantages I might have derived from that kind of association.

I may have evaded the payment of duties to the custom house; but I have never ceased to be a good citizen; and all the offences I have committed I was forced to by certain vices in our laws. In short, sir, I make you the depository of the secret on which perhaps depends the tranquility of our country; please to make such use of it as your judgment may direct. I might expatiate on this proof of patriotism but I let the fact speak for itself.

I presume, however, to hope that such proceedings may obtain amelioration of the situation of my unhappy brother, with which view I recommend him particularly to your influence. It is in the bosom of a just man, of a true Amercian, endowed with all other qualities that are honoured in society, that I think I am depositing the interests of our common country and that particularly concerns myself.

Our enemies have endeavored to work on me by a motive which few men would have resisted. They represented to me a brother in irons, a brother who is to me very dear; whose deliverer I might become, and I declined the proposal. Well persuaded of his innocence, I am free from apprehension as the issue of a trial, but he is sick and not in a place where he can receive the assistance his state requires. I recommend him to you, in the name of humanity.

As to the flag of truce, I have done with regard to it everything that prudence suggested to me at the time. I have asked fifteen days to determine, assigning such plausible pretexts, that I hope the term will be granted. I am waiting for the British officer’s answer, and for yours to this. Be so good as to assist me with your judicious counsel in so weighty an affair.

I have the honour to salute you,

J. Lafitte.

Through Mr. Blanque, Lafitte addressed a letter to Governor Claiborne, in which he stated very distinctly his position and desires. He penned the following:

Sir,

In the firm persuasion that the choice made of you to fill the office of first magistrate of this state was dictated by the esteem of your fellow-citizens and was conferred on merit, I confidently address you on an affair on which may depend the safety of this country.

I offer to you to restore to this state several citizens who perhaps, in your eyes have lost that sacred title. I offer you them, however, such as you could wish to find them, ready to exert their utmost efforts in defence of the country. This point of Louisiana, which I occupy, is of great importance in the present crisis. I tender my services to defend it; and the only reward I ask is that a stop be put to the proscription against me and my adherents, by an act of oblivion for all that has been done hitherto. I am the stray sheep, wishing to return to the sheepfold. If you were thoroughly acquainted with the nature of my offences, I should appear to you much less guilty, and still worthy to discharge the duties of a good citizen. I have never sailed under any flag but that of the republic of Carthagena, and my vessels are perfectly regular in that respect. If I could have brought my law- ful prizes into the ports of this state, I should not have employed the illicit means that have caused me to be proscribed. I decline saying more on the subject until I have the honour of your excellency’s answer, which I am persuaded can be dictated only by wisdom. Should your answer not be favorable to my ardent desires, I declare to you that I will instantly leave the country, to avoid the imputation of having co-operated towards an invasion on this point, which cannot fail to take place, and to rest secure in the acquittal of my own conscience.

I have the honour to be

Your excellency’s, &c.

J. Lafitte.

This packet of letters to John Blanque, Lafitte in trusted to the keeping of a trusted lieutenant and adviser, Rancher, by name. The latter made all haste to New Orleans, and in person delivered the letters to the member of the Legislature.

While Lafitte was thus sending word of the designs of the English to the proper authorities the brig Sophia still lay off Grande Terre and to keep the British officers there until he would receive instructions from the Governor the wily pirate leader despatched the following letter to Captain Lockyer:

Sir,

The confusion which prevailed in our camp yesterday and this morning, and of which you have a complete knowledge, has prevented me from answering: in a precise manner to the object of your mission; nor even at this moment can I give you all the satisfaction that you desire; however, if you could grant me a fortnight, I would be entirely at your disposal at the end of that time — this delay is indispensable to send away the three persons who have alone occasioned all the disturbance — the two who were the most troublesome are to leave this place in eight days, and the other is to go to town — the remainder of the time is necessary to enable me to put my affairs in order. — You may communicate with me, in sending a boat to the eastern point of the pass, where I will be found. You have inspired me with more confidence than the admiral, your superior officer, could have done himself; with you alone I wish to deal, and from you also I will claim, in due time, the reward of the service which I may render to you.

Be so good, sir, as to favour me with an answer, and believe me yours, &c.

J. Lafitte.

The contents of the packet Rancher delivered to Representative Blanque evidently created consternation in the official circles of the city, already apprehensive of a sudden descent of the English forces on the rich and altogether unprotected city.

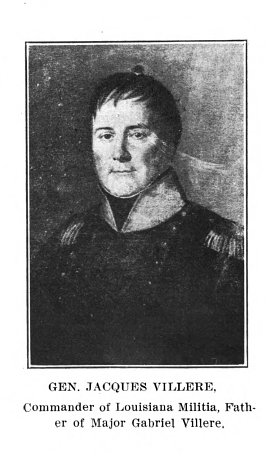

John Blanque at once repaired to Governor Claiborne’s offices and the Governor quickly summoned his military and naval advisers to consider the matter in full. They were Major-General Jacques Villere, Commodore Patterson, of the United States navy and Col. Ross of the regular army. The Governor submitted the letters to his council, asking for a decision on these two questions: First, whether the letters were genuine? Second, whether it was proper that the Governor should hold intercourse or enter into any correspondence with Lafitte and his associates? To each of these questions a negative answer was given, Major-General Villere alone dissenting. This officer being (as well as the Governor who, presiding in the council, could not give his opinion), not only satisfied as to the authenticity of the letters of the British officers but believing that the Baratarians might be employed in a very effective manner in case of invasion.

Collector Dubourg, in charge of the customs for the Government in New Orleans, was particularly insistent that this pirates’ stronghold, or smugglers’ retreat, be done away with and the more law-conforming merchants of the city were backing him up in his demands that the State assist the Government as it was sworn to do.

While Lafitte’s proffer of help to the constituted authorities was being turned down, Rancher, the Baratarian who delivered the letters to John Blanque, and even the august member of the legislature, were not unbusy if the public prints of the day are to be believed.

Just exactly what were Rancher’s actions after visiting Blanque at his home are unknown, but the day after his arrival the New Orleans newspapers carried the following advertisement:

$1,000 REWARD.

Will be paid for the apprehension of PIERRE LAFITTE, who broke and escaped last night from the prison of the parish. Said Pierre Lafitte is about five feet ten inches in in height, stout made, light complexion, and somewhat cross-eyed; further description is considered unnecessary, as he is very well known in the city.

Said Lafitte took with him three negroes, (giving their names and those of their owners). The above reward will be paid to any person delivering the said Lafitte to the subscriber.

J. H. Holland.

Keeper of the Prison.

Together the messenger and the elder Lafitte made their way back to the “Temple,” using the light, swiftailing pirogues for threading the devious waterways of the Louisiana lowlands. Holland, the jailer, being left to wave his thousand dollars’ reward around the various coffee houses in Rue Royal and Chartres Street and answer the quips and jibes that the letter-writers of that day furnished the badly-typed columns of the Louisiana Gazette.

While Pierre was on his way back to the stronghold Jean intercepted a letter that contained a warning of the British intentions toward New Orleans. This he promptly despatched in a letter of his own to John Blanque, in which he again proclaimed his devotion to his adopted country.

Grande Terre, 7th. September, 1814.

Sir,

You will always find me eager to evince my devotedness to the good of the country, of which I endeavoured to give some proof in my letter of the 4th, which I make no doubt you received. Amongst other papers that have fallen into my hands, I send you a scrap which appears to me of sufficient importance to merit your attention.

Since the departure of the officer who came with the flag of truce, his ship, with two other ships of war, have remained on the coast, within’sight. Doubtless this point is considered as important. We have hitherto kept on a respectable defensive; if, however, the British attach to the possession of this place the importance they give us rooni to suspect they do, they may employ means above our strength. I know not whether, in that case, proposals of intelligence with government would be out of season. It is always from my high opinion of your enlightened niind, that I request you to advise me in this affair.

I have the honour to salute you,

J. Lafitte.

No doubt the “Temple” witnessed the finest celebration it could boast when Rancher arrived with the “crosseyed” Pierre. Just what was done — exactly what form of the celebration took will never be known, but in the collection of Lafitte letters the following from Pierre, the elder, is found:

Grande Terre, 10th September, 1814.

Sir,

On my arrival here I was informed of all the occurrences that have taken place; I think I mav justly commend my brother’s conduct under such difficult circumstances. I am persuaded he could not have made a better choice than in making you the depositary of the papers that were sent to us and which may be of great importance to the state. Being fully determined to follow the plan that may reconcile us with the government, I herewith send you a letter directed to his excellency the governor, which I submit to your discretion, to deliver or not, as you may think proper. I have not yet been honored with an answer from you. The moments are precious; pray send me an answer that may serve to direct my measures in the circumstsances in which I find myself.

I have the honour to be, &c.

P. Lafitte.

But the only apparent result of Lafitte’s act of loyalty and warning was to hasten the steps that had been previously commenced, and which Col. Ross, Commodore Patterson, backed by the United States collector Duborg, insisted upon, to fit out an expedition to Barataria to break up Lafitte’s establishment. In the meantime, the two weeks asked for by Lafitte to consider the British proposal, having expired, Captain Lockyer appeared off Grand Terre, and hovered around the inlet several days, anxiously awaiting the answer of Lafitte. At last, his patience being exhausted, and mistrusting the intentions of the Baratarians, he retired. It was about this time that the spirit of Lafitte was sorely tried by the intelligence that the constituted authorities, whom he had supplied with such valuable information, instead of appreciating his generous exertions in behalf of his country, were actually equipping an expedition to destroy his establishment.

“This was truly an ungrateful return for services, which may now be justly estimated,” declares Judge Walker in his excellent history. “Nor is it satisfactorily shown that mercenary motives did not mingle with those which prompted some of the parties engaged in this expedition.

“The rich plunder of the ‘Pirate’s Retreat,’ the valuable fleet of small coasting vessels that rode in the Bay of Barataria, the exaggerated stories of a vast amount of treasure, heaped up in glittering piles, in dark, mysterious caves, of chests of Spanish doubloons, buried in the sand contributed to inflame the imagination and avarice of some of the individuals who were active in getting up this expedition.

“A naval and land force was organized under Commodore Patterson and Colonel Ross, which proceeded to Barataria, and with a pompous display of military power, entered the Bay. The Baratarians at first thought of resisting with all their means, which were considerable. They collected on the beach armed, their cannon were placed in position, and matches were lighted, when lo! to their amazement and dismay, the stars and stripes became visible through the mist.

“Against the power which that banner proclaimed, they were unwilling to lift their hands. They then surrendered, a few escaping up the Bayou in small boats. Lafitte, conformably to his pledge, on hearing of the expedition, had gone to the German coast as it is called — above New Orleans, his brother with him. Commodore Patterson seized all the vessels of the Baratarians and, filling them and his own with the rich goods found on the island, returned to New Orleans loaded with spoils. The Baratarians, who were captured, were ironed and committed to the calaboose. The vessels, money and stores taken in this expedition were claimed as lawful prizes by Commodore Patterson and Colonel Ross. Out of this claim grew a protracted suit, which elicited the foregoing facts, and resulted in establishing the innocence of Lafitte of all other offences but those of privateering — or employing persons to privateer against the commerce of Spain under commissions from the Republic of Colombia and bringing his prizes to the United States, to be disposed of contrary to the provisions of the Neutrality Act.

“The charge of piracy against Lafitte, or even against the men of the association of which he was the chief, remains to this day unsupported by a single particle of direct and positive testimony. All that was ever adduced against them, of a circumstantial or inferential character, was the discovery among the goods taken at Barataria of some jewelry which was identified as that of a Creole lady, who had sailed from New Orleans seven years before and was never heard of afterwards.

“Considering the many ways in which such property might have fallen into the hands of Baratarians, it would not be just to rest so serious a charge against them on this single fact. It is not at all improbable — though no facts of that character ever came to light — that among so many desperate characters attached to the Baratarian organization, there were not a few who would, if the temptation were presented, ’scuttle ship, or cut a throat’ to advance their ends, increase their gains, or gratify a natural bloodthirstiness.

“But such deed’s cannot be associated with the name of Jean Lafitte, save in the idle fictions by which the taste of the youth is vitiated, and history outraged and perverted. That he was more of a patriot than a pirate, that he rendered services of immense benefit to his adopted country, and should be held in respect and honor, rather than defamed and calumniated will, we think, abundantly appear to the reader,” sums up Walker.

“But was this loyalty anything more than strategem?” asks Cable. “The Spaniard and Englishman were Lafitte’s foe and his prey. The Creoles were his friends. His own large interests were scattered all over Lower Louisiana. His patriotism has been overpraised; and yet we may allow him patriotism. His whole war, on the main-land side, was only with a set of ideas not superficially fairer than his own. They seemed to him unsuited to the exigencies of the times and the country. Thousands of Louisianians thought as he did. They and he — to borrow from a distance the phrase of another, were ‘polished, agreeable, dignified, averse to baseness and vulgarity.’ They accepted friendship, honor and party faith as sufficient springs of action, and only dispensed with the sterner question of right and wrong. . True, Pierre, his brother, and Dominique You, his most intrepid captain, lay then in the calaboza. Yet should he, so able to take care of himself against all comers and all fates, so scornful of all subordination, for a paltry captain’s commission and a doubtful thirty thousand, help his life-time enemies to invade the country and city of his commercial and social intimates?”

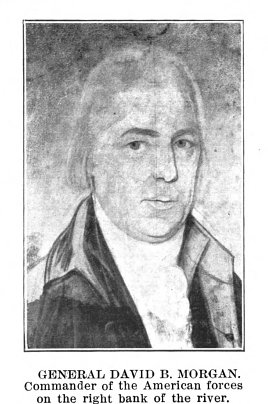

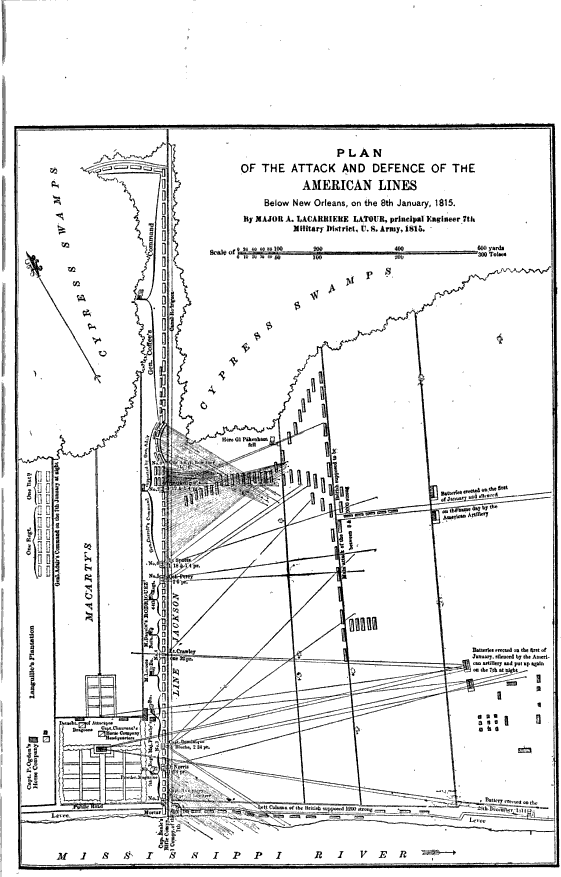

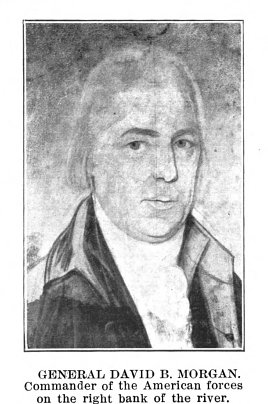

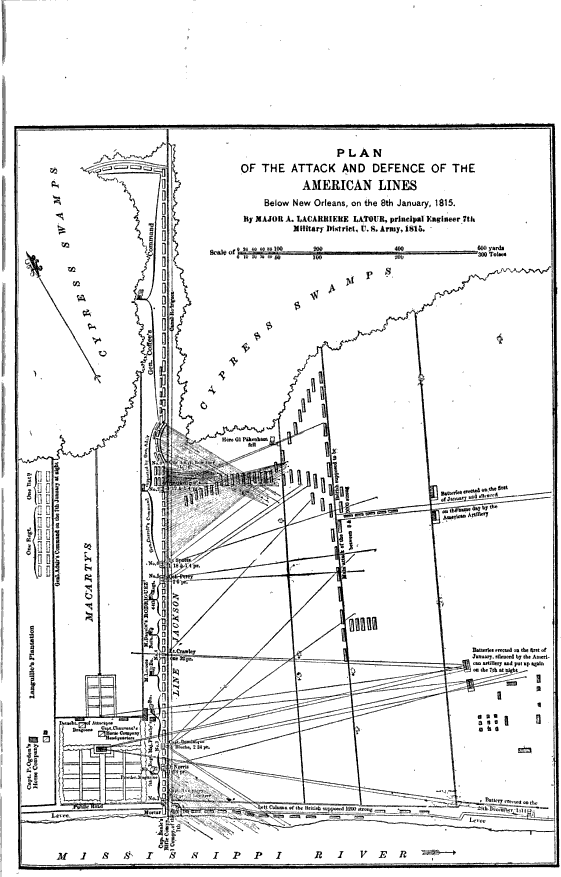

But pirate or patriot, or both, Jean Lafitte and his men were on the firing line when England’s trained hosts invaded Louisiana. This, we of 1915, know. His two lieutenants, Dominique You and Bluche, on January 1st won imperishable fame by the handling of cannon that out-shot the trained artillerists of Pakenham; Pierre Lafitte was given a position of trust the morning of the memorable 8th of January, after the British troops had thrown the American forces on the right bank of the river into confusion, and last, but not least, when General Jackson was mystified as to what direction the invading army would strike the city he was defending, he sent Jean Lafitte to the Barataria region with a strong force to guard against a rear attack from the Gulf. Here the “corsair”, he of the thousand vices but of the single virtue that will never die, under the gnarled oaks that sprouted from the shell mound at the junction of Little Barataria and Big Barataria bayous, lay ready to hurl back the minions of the government that had sought to buy his honor with gold and emoluments, as decisively as the Tennessee and Kentucky riflemen actually did on the plains of Chalmette.

“General Jackson, in his correspondence to the Secretary of War, did not fail to notice the conduct of the ‘corsairs of Barataria’.” Major Latour tells us while giving full credit to the services of Jean Lafitte and his band, “they were employed in the artillery service and in the course of the campaign they proved, in an unequivocal manner, that they had been misjudged by the enemy who had hoped to enlist them in his cause.

“Many of them were killed or wounded in the defense of their country. Their zeal, their courage, and their skill, were remarked by the whole army who could no longer consider such brave men as criminals, or avoid wishing their permanent return to duty and the favor of the government. These favorable sentiments were expressed by the legislature of the State, in a memorial to the President, and General Jackson added his and those of the army. The Chief Magistrate of our Government yielded to these intercessions and issued a proclamation by which he granted full and complete pardon to all those who had aided in repulsing the enemy.”

After the great battle Lafitte and his men practically passed out of the life of Louisiana. On the honors gained by the President’s pardon Dominique You settled down to a quiet life, “enjoying the vulgar admiration which is given the survivor of lawless adventures;” says one writer who evidently never thrilled himself over Jean Lafitte and his crew. “It may seem superfluous to add,” says this same writer, “that he became a leader in ward politics.” However, in 1830 all that was mortal of the chief gunner of Jackson’s Battery No. 3, was laid to rest with military honors, at the expense of the city, and followed on his way by the Louisiana Legion.

The visitor to New Orleans to-day may see his tomb in the middle walk of what is known as St. Louis Cemetery No. 3. The tablet bears his name surmounted by the emblem of Free Masonry. An epitaph, in French verse, proclaims him the “intrepid hero of a hundred battles on land and sea; who, without fear and without reproach, will one day view, unmoved, the destruction of the world,” being taken from Voltaire’s “La Henriade.”

Of Beluche we only know that after peace had descended upon his native city, for he was a Creole, he became the commodore of the navy of Venezuela.

Of Pierre Lafitte we know nothing, and of Jean but little more. In 1818 he had a fleet out under the Colombian flag, later he formed a colony on the island now occupied by the City of Galveston, and his name, if not his person, was the terror of the Gulf of Mexico in 1821-22, but his end is lost in a maze of tradition and thus lost to history.

His men, the Baratarians, their days of smuggling over, straggled back to their old haunts and became fishermen, crabbers, shrimpers and oyster men. And there today, in the great lowland sections of Louisiana, their descendants live on the “chenieres” (islands on which oaks grow) and they will tell you in low musical tones what a great man Lafitte was and how he saved Louisiana by changing Lafitte, the pirate, to Lafitte, the patriot.

chapter three.

JACKSON ARRIVES IN NEW ORLEANS.

Of the mode of General Jackson’s entrance into New Orleans we have a pleasant and picturesque account from the pen of Alexander Walker, long a distinguished resident of the Crescent City, and author of the little work entitled “Jackson and New Orleans;” one of the best executed and most entertaining pieces of American history in existence. What Judge Walker has told so interestingly and well, need not be told again in any words but his:

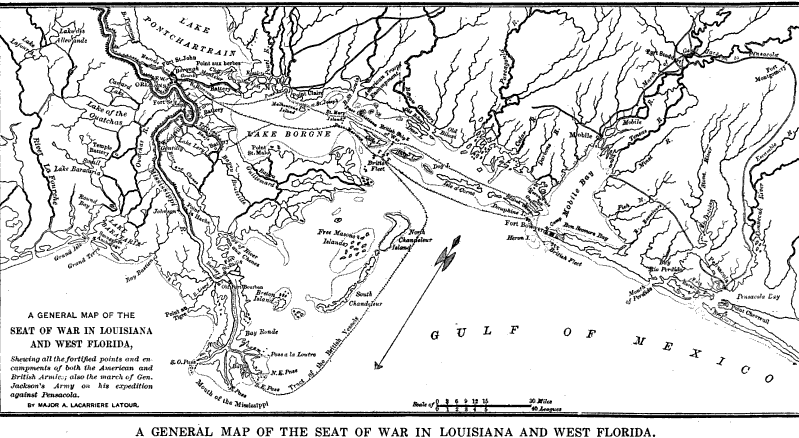

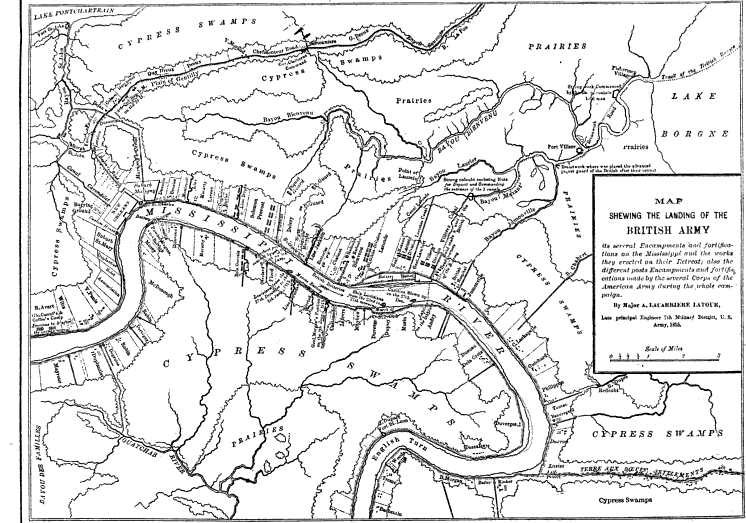

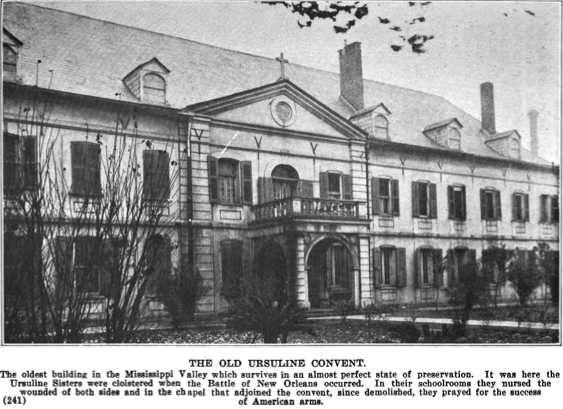

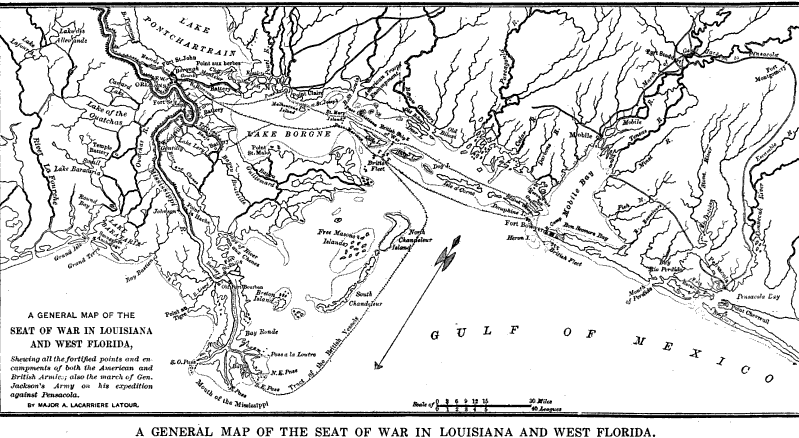

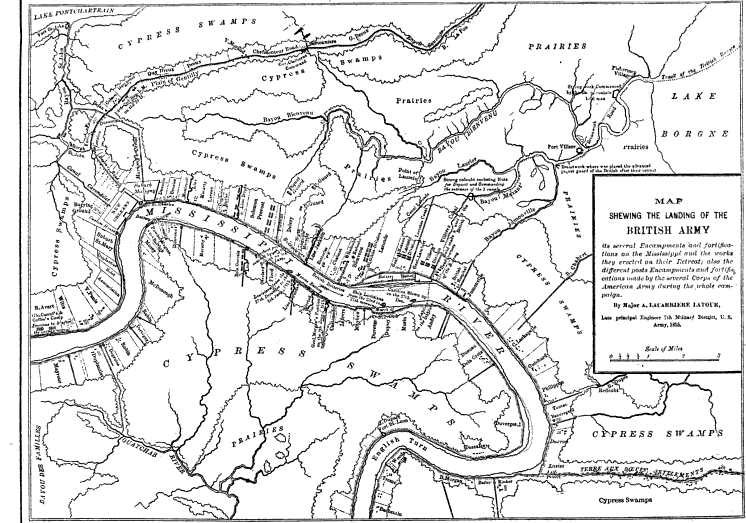

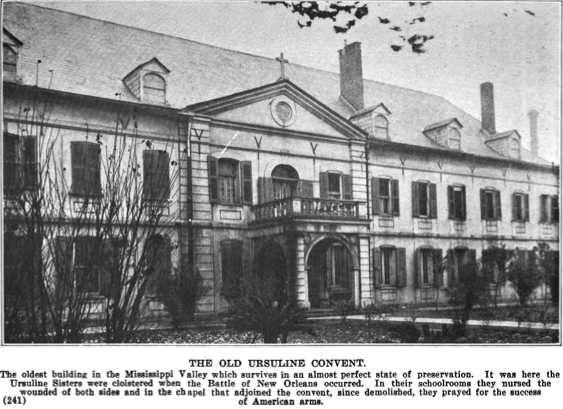

“The Bayou St. John enters into Lake Ponchartrain at a distance of seven miles from the city. Here at its mouth may be seen the remains in an excellent state of preservation of an old Spanish fort which was built many years ago by one of the Spanish Governors as a protection of this important point, for by glancing at the map of New Orleans and its vicinity, it will be seen that a maritime power could find no easier approach to the city than through the Bayou St. John. This fort was built as the Spaniards built all their fortifications in this State where stone could not be procured, of small brick imported from Europe cemented with a much more adhesive and permanent material than is now used for building and with walls of great thickness and solidity. The foundation and walls of the fort still remain, interesting vestiges of the old Spanish, dominion. On the mound and within the walls stands a comfortable hotel, where in the summer season (1855) may be obtained healthful cheer, generous liquors and a pleasant view of the placid and beautiful lake over whose gentle bosom the sweet south wind comes with just power enough to raise a gentle ripple on its mirror-like surface, bringing joy and relief to the wearied townsman and debilitated invalid.

“What a different scene did this fort present one hundred years ago! Then there were large cannon looking frowningly through those embrasures which are now filled up with dirt and rubbish, and around them clustered glittering bayonets and fierce-looking men full of military ardor and fierce determination. There, too, was much of a reality, if not of the pomp and circumstance of war. High above the fort from the summit of a lofty staff floated, not the showy banner of old Spain with its glittering and mysterious emblazonry, but that simplest and most beautiful of all national standards, the stars and stripes of the United States.

“From the Fort St. John to the city the distance is six or seven miles. Along the bayou which twists its sinuous course like a huge dark green serpent through the swamp, lies a good road hardened by a pavement of shells taken from the bottom of the lake. Hereon city Jehus in 1855 exercised their fast nags and lovely ladies took their evening airings. But at the time this narrative commences it was a very bad road, being low, muddy and broken. The ride which (at the time Walker wrote) occupied some twenty minutes very delightfully, was then a wearisome two hours’ journey.

“It was along this road early on the morning of the 2d of December, 1814, that a party of gentlemen rode at a brisk trot from the lake towards the city. The mist which during the night broods over the swamp had not cleared off. The air was chilly, damp and uncomfortable. The travelers, however, were evidently hardy men accustomed to exposure, and intent upon purposes too absorbing to leave any consciousness of external discomforts. Though devoid of all military display and even of the ordinary equipments of soldiers the bearing and appearance of these men betokened their connection with the profession of arms. The chief of the party, which was composed of five or six persons, was a tall, gaunt man of very erect carriage with a countenance full of stern decision and fearless energy, but furrowed with care and anxiety. His complexion was sallow and unhealthy; his hair was iron grey, and his body thin and emaciated like that of one who had just recovered from a lingering and painful sickness. But the fierce glare of his bright and hawk-like eye betrayed a soul and spirit which triumphed over all the infirmities of the body. His dress was simple and nearly threadbare. A small leather cap protected his head and a short Spanish blue cloak his body, whilst his feet and legs were encased in high dragoon boots, long ignorant of polish or blacking, which reached to the knees. In age he appeared to have passed about forty-five winters — the season for which his stern and hardy nature seemed peculiarly adapted.

“The others of the party were younger men whose spirits and movements were more elastic and careless and who relieved the weariness of the journey with many a jovial story.

“Arriving at the high ground near the junction of the Canal Carondelet with the Bayou St. John, where a bridge spanned the bayou and quite a village had grown up, the travelers halted before an old Spanish villa and throwing their bridles to some negro boys at the gates, dismounted and walked into the house. On entering the gallery they were received in a very cordial and courteous manner by J. Kilty Smith, Esq., then a leading New Orleans merchant of enterprise and public spirit. On the bayou in an agreeable suburban retreat Mr. Smith had established himself. Here he dispensed a liberal hospitality and lived in such a style as was regarded in those economical days, and by the more frugal Spanish and French populations, as quite extravagant and luxurious.

“Ushering them into the marble paved hall of his old Spanish villa, Mr. Smith soon made his guests comfortable. It was evident that they were not unexpected. Soon the company were all seated at the breakfast table which fairly groaned with the abundance of generous viands prepared in that style of incomparable cookery for which the Creoles of Louisiana are so renowned. Of this rich and savory food the younger guests partook quite heartily, but the elder and leader of the party was more careful and abstemious, confining himself to some boiled hominy whose whiteness rivaled that of the damask tablecloth. In the midst of the breakfast and whilst the company were engaged in discussing the news of the day, a servant whispered to the host that he was wanted in the ante-room. Excusing himself to his guests Mr. Smith retired to the ante-room and there found himself in the presence of an indignant and excited Creole lady, a neighbor, who had kindly consented to superintend the preparations in Mr. Smith s bachelor establishment for the reception of some distinguished strangers and who, in that behalf, had imposed upon herself a severe responsibility and labor.

“‘Ah, Mr. Smith!’ exclaimed the deceived lady, in a half reproachful, half indignant style, ‘how could you play such a trick upon me? You asked me to get your house in order to receive a great General. I did so. I worked myself almost to death to make your house comme il faut and prepared a splendid dejeuner, and now I find that all my labor is thrown upon an ugly old Kaintuck-flatboatman instead of your grand General, with plumes, epaulettes, long sword and mustache!’

“It was in vain that Mr. Smith strove to remove the delusion from the mind of the irate lady, and convince her that that plainly-dressed, jaundiced, hard-featured, unshorn man in the old blue coat and bullet buttons, was that famous warrior Andrew Jackson.

“It was indeed Andrew Jackson who had come fresh from the glories and fatigue of his brilliant Indian campaigns, in this unostentatious manner, to the city which he had been sent to protect from one of the most formidable perils that ever threatened a community. Cheerfully and happily had he embraced this awful responsibility. He had come to defend a defenceless city, situated in the most remote section of the Union — a city which had neither fleets nor forts, means nor men — a city whose population were comparatively strangers to that of the other States, who sprung from a different national stock, and spoke a different language from that of the overwhelming majority of their countrymen — a language entirely unknown to the General — to defend it, too, against a power then victorious over Napoleon, supposedly safe out of mischief on Elba.

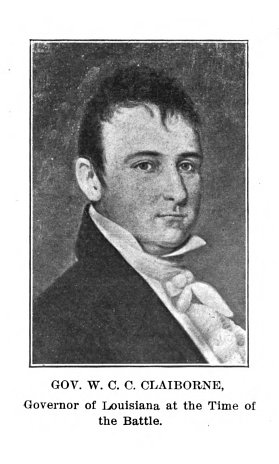

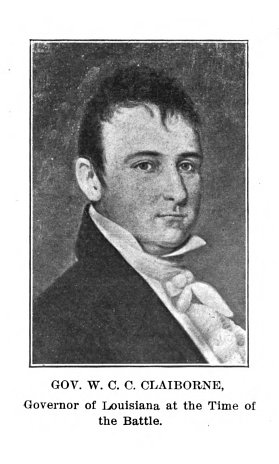

“After partaking of their breakfast the General, taking out his watch, reminded his companions of the necessity of their entrance into the city. In a few minutes carriages were procured and the whole party rode toward the city by the old Bayou road. The General was accompanied by Major Hughes, commander of the Ft. St. John, by Major Butler and Captain Reid, his secretary, who afterwards became one of his biographers, Major Chotard and other officers of the staff. The cavalcade proceeded to the elegant residence of Daniel Clark, the first representative of Louisiana in the Congress of the United States, a gentleman of Irish birth who had acquired great influence, popularity and wealth in the city, and died shortly after the commencement of the war of 1812. Here Jackson and his aides were met by a committee of the State and city authorities and of the people at the head of whom was the Governor of the State who, in earnest but rather rhetorical terms, welcomed the General to the city and proffered him every aid of the authorities and the people, to enable him to justify the title which they were already conferring upon him of ‘saviour of New Orleans.’ His excellency, W. C. C. Claiborne, the first American Governor of Louisiana, a Virginian of good address and fluent elocution, then in the bloom of life, was supported by the leading civil and military characters of the city. There in the group was that redoubtable naval hero Commodore Patterson, a stout, compact, gallant-bearing man, in the neat undress naval uniform. His manner was slightly marked by hauteur, but his movement and expression indicated the energy and boldness of a man of decided action, as well as confident bearing.

“Here, too, was the then Mayor of New Orleans, Nicholas Girod, a rotund, affable, pleasant old French gentleman, of easy, polite manners. There too, was Edward Livingstone, then the leading legal character in the city — a tall, high-shouldered man of ungraceful figure and homely countenance, but whose high brow and large thoughtful eyes indicated a profound and powerful intellect. By his side stood his youthful rival at the bar — an elegant, graceful and showily-dressed gentleman whose figure combined the compact dignity and solidity of the soldier with the ease and grace of the man of fashion and taste, and who, as the sole survivor of those named, retained in a remarkable degree the elegance and grace which characterized his bearing forty years ago to the day of his lamented decease. We refer to John R. Grymes, so long the veteran and chief ornament of the New Orleans bar.

“Such were the leading personages in the assembly which greeted Jackson’s entrance into New Orleans.

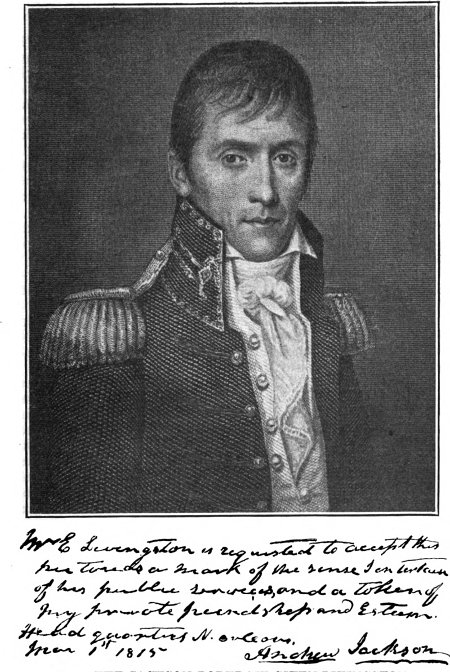

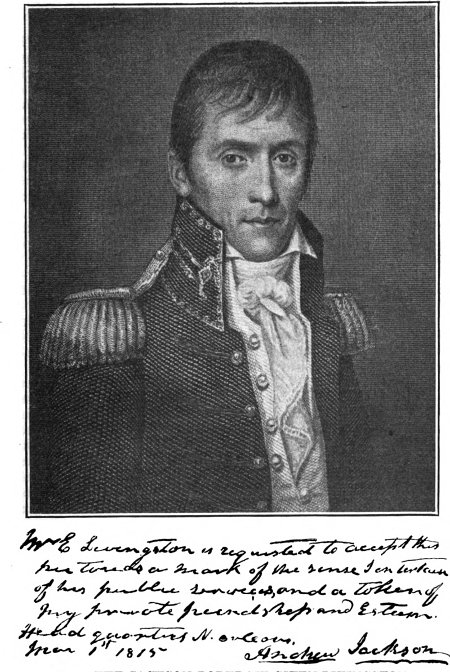

“The General replied briefly to the welcome of the Governor. He declared that he had come to protect the city and he would drive their enemies into the sea or perish in the effort. He called on all good citizens to rally around him in this emergency and, ceasing all differences and divisions, to unite with him in the patriotic resolve to save their city from the dishonor and disaster which a presumptuous enemy threatened to inflict upon it. This address was rendered into French by Mr. Livingstone. It produced an electric effect upon all present. Their countenances cleared up. Bright and hopeful were the words and looks of all who had heard the thrilling tones and caught the heroic glance of the hawk-eyed General. The General and staff then re-entered their carriages. A cavalcade was formed and proceeded to the building, 106 Royal street — one of the few brick buildings then existing in New Orleans, which stood but little changed or effected by the lapse of so many years, until torn down to make way for the new courthouse. A flag unfurled from the third story soon indicated to the population the headquarters of the General who had come so suddenly and quietly to their rescue.”

Jackson had come! There was magic in the news. Every witness living and dead testified to the electric effect of the General’s quiet and sudden arrival. There was a truce at once to indecision, to indolence, to incredulity, to factious debate, to paltry contentions, to wild alarm. He had come, so worn down with disease and the fatigue of his ten days’ ride on horseback that he was more fit for the hospital than the field. But there was that in his manner and aspect which revealed the master. That will of his triumphed over the languor and anguish of disease, and everyone who approached him felt that the man for the hour he was there.

He began his work without the loss of one minute. The unavoidable formalities of his reception were no sooner over than he mounted his horse again and rode out to review the uniformed companies of the city. These companies consisted then of several hundred men, the elite of the city — merchants, lawyers, the sons of planters, clerks and others, who were well equipped and not a little proud of their appearance and discipline. The General complimented them warmly, addressed the principal officers, inquired respecting the numbers, history and organization of the companies, and left them captivated with his frank and straightforward mode of procedure.

chapter four.

JACKSON’s FIRST “CONQUEST” OF NEW ORLEANS.

Jackson’s first conquest of New Orleans differed so from the conquest that made him president, that it deserves more than a passing mention. Rough of speech, fond of telling stories that would go better around a soldier’s campfire than in an aristocrat’s drawing room, and given to expressing himself in language that shocked the gentle members of his committee of defense, the Creoles of New Orleans, contrary to their usual course of action whenever any person of distinction visited the city, did not invite the gaunt, swearing and crude major general to their homes.

Jackson had been planning the defense of New Orleans some days before he made his polite bow to society of the city. Edward Livingston, who was the General’s military secretary, learned that his wife, herself a full-blooded French Creole and an acknowledged leader of the society of her Creole city, was to give a dinner to a party of belles of the intimate circle she ruled, told her that he had invited Jackson to attend and that the General had accepted.

Mrs. Livingston, who had heard some of the many tales of the rough Jackson, as had every first family in town, was dismayed and took her lawyer husband to task for having such a disregard of the amenities as to bring “that wild Indian-fighter from Tennessee to a dinner party of young ladies!” Her husband smiled as he was berated and bidding his wife remain calm until she saw the fire-eater, added, “He will capture you at first sight.”

Livingston afterwards told the story with great glee. He described how the hero of Horseshoe Bend and Pensacola clattered up to the Livingston domicile on horseback, a.nd how the party of Creole belles sat stiffly in the drawing room holding, their breaths in awe of the contretempts they felt was to follow.

“I ushered General Jackson into the drawing room and presented him to Madame who was surrounded by a dozen or more young ladies,” said Livingston. “The General was in the full-dress uniform of his rank — that of major general in the regular army. This was a blue frock-coat with buff facings and gold lace, white waistcoat and close fitting breeches, also of white cloth, with morocco boots reaching above the knees.

“To my astonishment this uniform was new, spotlessly clean and fitted his tall, slender form perfectly. I had seen him before only in the somewhat worn and careless fatigue uniform he wore on duty at headquarters. I had to confess to myself that the new and perfectly fitting full-dress uniform made almost another man of him.

“I also observed that he had two sets of manners: One for the headquarters, where he dealt with men and the problems of war: the other for the drawing-room, where he met the gentler sex and was bound by the etiquette of fair society. But he was equally at home in either. When we reached the middle of the room all the ladies rose. I said: ‘Madame and Mesdemoiselles, I have the honor to present Major-General Jackson of the United States Army.’

“The General bowed to Madame, and then right and left to the young ladies about her. Madame advanced to meet him, took his hand and then presented him to the young ladies severally, name by name. Unfortunately, of the twelve or more young ladies present — all of whom happened to be French — not more than three could speak English; and as the General understood not a word of French — except, perhaps, Sacre bleu — general conversation was restricted.

“However, we at once sought the table, where we placed the General between Madame Livingston and Mile. Eliza Chotard, an excellent English scholar, and with their assistance as interpreters, he kept up a lively all-round chat with the entire company. Of our wines he seemed to fancy most a fine old Maderia and remarked that he had not tasted anything like it since Burr’s dinner at Philadelphia in 1797 when he (Jackson) was a senator. I well remembered that occasion, having been then a member of Congress from New York and one of Burr’s guests.

“‘So you have known Mr. Livingston a very long time,’ exclaimed Mile. Chotard.

“‘Oh yes, Miss Chotard,’ he replied, ‘I had the honor to know Mr. Livingston probably before the world was blessed by your existence.”

“This was only one among a perfect fusillade of quick and apt compliments he bestowed with charming impartiality upon Madame Livingston and all her pretty guests.

When the dinner was over he spent half an hour or so with me in my library when he returned to the drawing room to take leave of the ladies, as he still had much work before him at headquarters that night. During the whole occasion the ladies, who thought of nothing but the impending invasion, wanted to talk about it almost exclusively. But he gently parried the subject. The only thing he said about it that I can remember was to assure Madame that while ‘possibly the British soldiers might get near enough to see the church-spires that pointed to heaven from the sanctuaries of your religion, none should ever get even a glimpse of the inner sanctuaries of your homes.’ I confess that I myself more than once marvelled at the unstudied elegance of his language and even more at the apparently spontaneous promptings of his gallantry.”

It has since been pointed out that Livingston was not the only man in New Orleans whom Jackson puzzled in this respect. Rough as he was, he possessed a trait of gentle chivalry which only the society of the gentler sex could ever call forth. It was in singular contrast to the sententious autocracy of speech and manner that so often characterized his intercourse with men in public affairs.

“When the General was gone,” Livingston records, “the ladies no longer restrained their enthusiasm. ‘Is this your savage Indian-fighter?’ they demanded in a chorus of their own language. ‘Is this your rough frontier General? Shame on you, Mr. Livingston, to deceive us so! He is a veritable preux chevalier!’ And I must confess that Madame was as voluble in her reproaches as any of the young ladies. I was glad to escape in a few minutes, when I went to join the General at headquarters, where we were busy until near two a. m. with the preliminary work of the campaign.”

When Madame Livingston’s gay guests dispersed that evening, they carried tidings of Jackson’s first “conquest” of New Orleans far into the homes of the elete of Creole society. Wonderful stories concerning the suavity and aplomb of the great American general, who was to protect them and their sanctuaries from invasion and rapine, were told — and believed. He captivated the women of the city as successfully as he commanded the men.

chapter five.

THE BATTLE OF THE GUN BOATS.

(December 14, 1814)

“A storm on the 9th of December, 1814, greeted the first appearance of the British fleet off the coast of the Gulf of Mexico,” writes Judge Alexander Walker in his entertaining “Jackson and New Orleans.”

“To minds less buoyant and confident than those of the sanguine and hitherto irresistible veterans of that gallant array of naval and military power this occurrence might have appeared as an evil augury. Soon, however, the storm lulled, the clouds passed quickly away and the bright sun came forth to cheer the hearts of the crowded crews. A favorable wind bears the squadron rapidly onward in the direction of the entrance of Lake Borgne. The huge Tonnant, the same which was captured at Abouquir in Nelson’s great fight, after the gallant Dupetit Thouars had flooded her decks with his noble blood that flowed from a dozen wounds, now commanded by the white-haired British Vice-Admiral, and the gallant Sea-horse, with her corklegged Captain, lead the van. Behind follow the long train of every variety of sailing craft, from the great ships of war, with their frowning batteries, to the little trim sloops and schooners of fifteen or twenty ton, designed to penetrate the bays and inlets of the coast.

“The pilots, who have accompanied the fleets from the West Indies, have announced that the land is not far off and all parties are on deck, eagerly straining their eyes for a view of the desired shore. There, in the distance, they soon discover a long, shingling white line, which sparkles in the sun like an island of fire. Presently it becomes more distinct and substantial and the man at the look-out proclaims ‘land ahead’. The leading ships approach as near as is prudent and their crews, especially the land troops, experience no little disappointment at the bleak and forbidding aspect of Dauphine island, with its long, sandy beach, its dreary, stunted pines, and the entire absence of any vestige of settlement or cultivation. Turning to the west, the fleet avoids the island and proceeds towards a favorable anchorage in the direction of the Chandeleur islands, the wind in the meantime having chopped around and blowing too strong from the shore to justify an attempt to enter the lake at night.

“As the Tonnant and Sea-horse pass near to Dauphine Island, the attention of the Vice-Admiral is called to two small vessels, lying between the island and the shore. They are neat little craft, sloop-rigged, and evidently armed. They appear to be watching the movements of the British ships and when the latter take a western course, they weigh anchor and follow in the same direction. At night-fall the signal ‘to anchor’ is made from the Tonnant and the order is quickly obeyed by all the vessels in the squadron.

“The suspicious little sloops, as if in apprehension of a night attack of boats, then press all sail and proceed in the direction of Biloxi Bay. They prove to be the United States gunboats No. 23, Lieutenant McKeever, (afterwards Commodore McKeever), No. 163, Sailing Master Ulrick, which had been detached from the squadron of Lieutenant Thomas Ap Catesby Jones (later the Commodore Jones who ran up the first American flag at Monterey, California, in 1847), who had been sent by Commodore Patterson with six gunboats, one tender, and a despatch boat, to watch and report the approach of the British. In case their fleet succeeded in entering the lake, he was to be prepared to cut off their barges and prevent the landing of the troops. If hard pressed by a superior force, his orders were to fall back upon a mud fort, the Petites Coquilles, near the mouth of the Rigolets and shelter his vessels under its guns.

“The two boats which had attracted the notice of the British Vice-Admiral, joined the others of the squadron that night near Biloxi. The next day, the 10th of December, at dawn, or as soon as the fog cleared off, Jones was amazed to observe the deep water between Ship and Cat Islands where the current flows, crowded with ships and vessels of every calibre and description. The Tonnant having anchored off the Chandeleurs, the Sea-horse was now the foremost ship. Jones immediately made for Pass Christian with his little fleet, where he anchored, and quietly awaited the approach of the British vessels.

“In compact and regular order, the fleet moved slowly through the passage between Cat and Ship Islands and along the east coast of the former island presenting, under a bright sun and cloudless sky, a most impressive marine panorama. Soon, however, the soundings warned

the British that they were getting into shallow water and the line-of-battle ships came to anchor. They were now, however, safe within American waters, almost in Lake Borgne, and preparations were actively commenced to relieve the ships of the impatient and restless mass of belligerent mortality with which they were crowded. The troops were therefore embarked on the transports and smaller vessels. Before, however, the landing could be attempted, it was necessary to clear the lake of the agile and well-managed little American gunboats, which hovered in their front and appeared ready to pounce down on any smaller craft that might trust themselves too far from the shelter of the batteries of the ships of the line.

“Vice-Admiral Cochrane, who directed all the movements relating to the landing of the troops, proceeded to organize an expedition of barges to attack and destroy the gun-boats. The command of this enterprise was confided to Captain Lockyer, the same naval officer who endeavored to persuade Jean Lafitte to come over to the English, who was presumed to be better acquainted with the coast than any other officer. Captain Lockyer had also commanded one of the sloops in the attack of Fort Bowyer and, no doubt, longed for an opportunity of wiping from the escutcheon of the British Navy the disgrace of that defeat. All the launches, barges and pinnaces of the fleet were collected together. The barges had been made expressly for this expedition, and were nearly as large as Jones’ gunboats, each carrying eighty men. To these were added the gigs of the Tonnant and Sea-horse. There were forty launches, mounting each one carronade 12, 18 or 24 calibre; one launch, with one long brass pounder; another with a brass nine-pounder; and three gigs, with small arms. There were, therefore, in all, forty-five boats and forty-two cannon, manned by a thousand sailors and marines picked from the crews of the ships.

“Captain Lockyer was ably seconded in the organization and direction of this formidable fleet by his subordinates, Montressor of the Manly, and Roberts of the Meteor, both veteran and experienced officers.

“On the evening of the 12th the flotilla moved in beautiful order from the anchorage of the squadron near Ship Island, in the direction of Pass Christian. It consisted of three divisions under the three officers named. Gallantly, and in perfect line, these divisions advanced along the white shores of what is now the coast of the State of Mississippi for a distance of thirty-six miles, the boats being rowed by the hardy sailors, without resting.

“When morning broke on the 13th, the flotilla had arrived near the Bay of St. Louis, whither three of the barges were detached to capture the small schooner Sea-horse, which Jones had sent into the bay for the purpose of removing some stores deposited there.

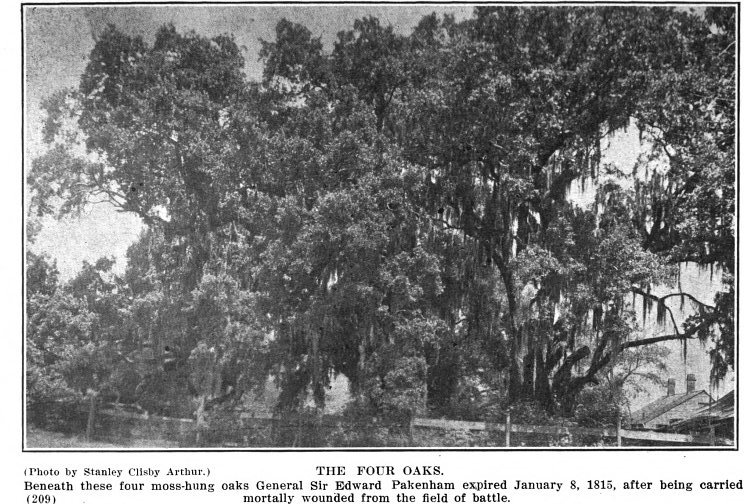

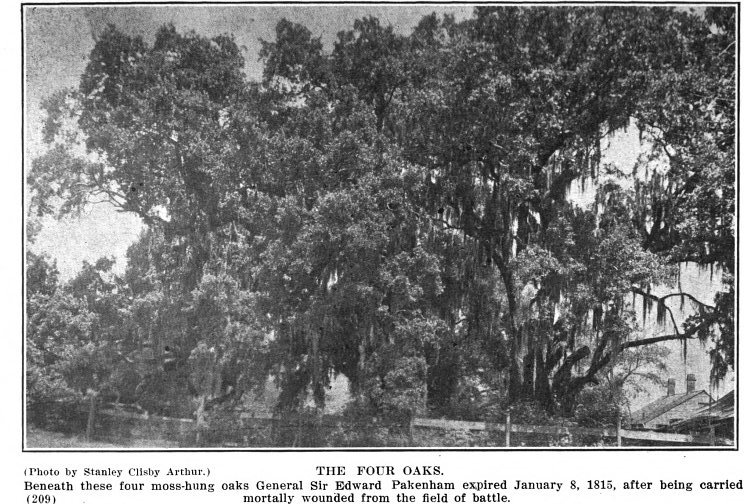

“As soon as the barges came within range of her guns, the Sea-horse opened upon them a well-directed and effective fire. At the same time two six pounders, placed in battery on the shore, followed up the discharge of the Seahorse and, striking the barges, wounded several of the men. The barges then drew off towards the main body of the flotilla when, thinking they had retired for reinforcement and apprehending a renewal of the attack by the whole force of Lockyer, the captain of the Sea-horse blew her up and set fire to the stores on shore, which were entirely destroyed.