Longfellow, Henry Wadsworth, 1807-1882

Scudder, Horace Elisha, 1838-1902

Longfellow, Alice M. (Alice Mary), 1850-1928

This book was produced in EPUB format by the Internet Archive.

The book pages were scanned and converted to EPUB format automatically. This process relies on optical character recognition, and is somewhat susceptible to errors. The book may not offer the correct reading sequence, and there may be weird characters, non-words, and incorrect guesses at structure. Some page numbers and headers or footers may remain from the scanned page. The process which identifies images might have found stray marks on the page which are not actually images from the book. The hidden page numbering which may be available to your ereader corresponds to the numbered pages in the print edition, but is not an exact match; page numbers will increment at the same rate as the corresponding print edition, but we may have started numbering before the print book's visible page numbers. The Internet Archive is working to improve the scanning process and resulting books, but in the meantime, we hope that this book will be useful to you.

The Internet Archive was founded in 1996 to build an Internet library and to promote universal access to all knowledge. The Archive's purposes include offering permanent access for researchers, historians, scholars, people with disabilities, and the general public to historical collections that exist in digital format. The Internet Archive includes texts, audio, moving images, and software as well as archived web pages, and provides specialized services for information access for the blind and other persons with disabilities.

Created with abbyy2epub (v.1.7.6)

Class V' o '£^ '2. U E Book ^ fi *

COPVRIGHT DEPOSIT.

ssued Weekly / Number I

March 17, 1886

»UHmtiinn4mi<:niumiiruof/riiUiMtmh»}\iimp.iU/imutaaumi//ittuiiiivwuutm^^

Single Numbers FIFTEEN CENTS Double Numbers THIRTY CENTS

Triple Numbers FORTY-FIVE CENTS Quadruple Numbers FIFTY CENTS Yearly Subscription $5.00

THE RIl/ERSIDE LIBRARY FOR YOUNG PEOPLE.

■4 series of volumes devoted to Historji, Biographv, Mechanics, Travel, Natural History, and Adventure. IVitb Maps, Portraits, etc. Designed especially for boys and girls who are laving the foundation of private libraries. Each volume, uniform; i6mo, y^ cents. Teachers' price, per volume, 64 cents, postpaid. Special price to libraries: each volume, 60 cents, postpaid ; the entire set of 11 volumes, $5.^0, not prepaid.

1. THE IV/IR OF INDEPENDENCE. By fohn Fiske. IVitb Maps. Pp. 200.

2. GEORGE IVASHINGTON. An Historical Biography. By Horace E. Scudder. fVilh 8 illustrations. Pp. 248.

J. BIRDS THROUGH AN OPERA-GLASS. By Florence A. Mcrriam. With 22 illustrations. Pp. 22}.

4. UP AND DOtVN THE BROOK'S. By Mary E. Barnford. IVith 55 illustrations. Pp. 222.

5. COAL AND THE COAL MINES. By Homer Greene, author of the Youth's Companion pri^e serial, " The Blind Brother." IVith /j illustrations. Pp. 246.

6. A NEIV ENGLAND GIRLHOOD, OUTLINED FROM MEMORY. By Lucy Larcom. Pp. 2^4.

Virtually an autobiography of the famous author.

7. JAVA: THE PEARL OF THE EAST. By Mrs. SJ. Higginson. fVith Index and Map. Pp. 204.

8. GIRLS AND IVOMEN. By E. Chester. Pp. 228.

9. A BOOK OF FAMOUS VERSE. Selected by Agnes Repplicr. With Notes, Index of Authors, Index of Titles, and Index of First Lines. Pp. 224.

10. JAPAN: IN HISTORY, FOLK-LORE, AND ART. By William Elliot Griffis, D. D. Pp. 2^0.

11. BRAVE LITTLE HOLLAND, AND WHAT SHE TAUGHT US. By William Elliot Griffi<, D. D. With 8 illustrations. Pp. 2^2.

Other vohnnes in preparation.

HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN AND COMPANY.

4 Park Street, Boston ; 11 East 1 yth Street, New York ; I ^8 Adams Street, Chicago.

p—^■"^""vesssE'

7» m^

5 A QA«^j>A 1. 2i^^-'-»-c^»

A SKETCH OF THE LIFE AND WRITINGS

OF

HENRY WADSWORTH LONGFELLOW.

I.

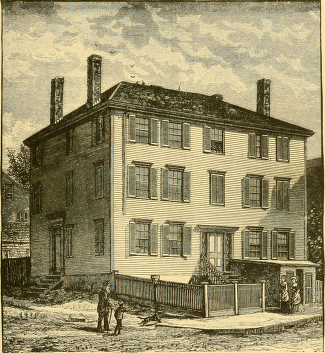

The house is still standing in Portland, Maine, — a large, square, wooden house at the corner of Fore and Hancock streets, — where Longfellow was horn, February 27, 1807. Longfellow's early life, however, was passed in what is known as the Longfellow House, a substantial brick mansion in Congress Street. Here lived his father, Stephen Longfellow, and his mother, Zilpha (Wadsworth) Longfellow. The father was a lawyer, who gathered honors through a long life, having been several times a member of the Massachusetts Legislature while Maine was a district of that State; a member of the Hartford Convention, for he was a stout Federalist; a presidential elector when Monroe was first elected ; and a member of the United States House of Representatives from 1823 to 1825. He died in 1849, after Evangeline had set its seal upon his son's growing reputation. The mother was daughter of General Peleg Wadsworth, who had fought in the Revolutionary War. Both parents were descended from Englishmen, who came to this country in the early days of the colony, and whose successors were marked men in the generations that followed. Upon his mother's side the poet ti'aced his ancestry to four of the Pilgrims who came in the Mayflower, two of these being Elder William Brewster and Captain John Alden.

iv HENRY WADSWORTH LONGFELLOW.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was the second son of the family, which contained four sons and four daughters. He took his name from his mother's brother. Lieutenant Henry Wadsworth, whose lieroic death was a fresh and tender memory in the family. Two years and a half before, on the night of September 4, 1804, he had been second in command of the bomb-ketch Litrepid, which was fitted up as an " infernal," and sent stealthily into the harbor of Tripoli to blow up the enemy's fleet. The officers and crew were to apply the match and escape in the boats; but when the Intrepid was still a quarter of a mile from her destination, the watching men in the American fleet outside saw a sudden line of light; in a moment a column of fire shot up from the vessel, and Avith a tremendous exj^losion bombs burst in every direction, and the masts and rigging flew into the air. Every soul on board perished. Something, perhaps, of this adventure entered into the poet's early associations, and deepened the ardor of his patriotism.

The sea, at any rate, and a sea-fight nearer home, made a part of his boyish recollections. In 1813, when he was six years old, the American brig Enterprise fell in with the English brig Boxer, outside of Portland harbor, and a fight took place, which could be heard from the shore. It lasted for three quarters of an hour, the Boxer's colors beingnailed to the mast. The Enterprise came into the harbor, bringing her captive, but both commanders had been killed in the engagement, and were buried side by side in the cemetery on Mount joy. In his poem My Lost Youth, Longfellow recalls the town g-s it then was, and this memorable fight: —

" I remember the black wharves aud the ships. And the sea-tides tossing free ; And Spanish sailoi-s with bearded lips, And the beauty and mystery of the ships, And the magic of the sea.

And the voice of that wayward song

MR. LONGFELLOW'S BIRTHPLACE, PORTLAND

Is singing and saying still: * A boy's will is the wind's will, And the thoughts of youth are long, long thoughts.'

" I remember the bulwarks by the shore, And the fort upon the hill; The sunrise gun, with its hollow roar. The drum-beat repeated o'er and o'er, And the bugle wild and shrill; And the music of that old song Throbs in my memory still: 'A boy's will is the wind's will. And the thoughts of youth are long, long thoughts.'

" I remember the sea-fight far away. How it thundered o'er the tide ! And the dead captains as they lay In their graves, o'erlooking the tranquil bay. Where they in battle died.

And the sound of that mournful song ■• Goes through me with a thrill:

' A boy's will is the wind's will, And the thoughts of youth are long, long thoughts."

In the same poem Longfellow speaks of the

" Gleams and glooms that dart Across the school-boy's brain."

The first school which he attended was a child's school, kept on Spring Street by a dame known in the New England vernacular as Marm Fellows. Later he went to the town school in Love Lane, now Centre Street, for a short time, and then to the private school of Nathaniel H. Carter, in a little one-story house on the west side of Preble Street, now Congress. He was prepared for college at the Portland Academy, which had for masters the same Mr. Cai'ter and Mr. Bezaleel Cushman, who subsequently was editor of the New York Evening Post. An usher, also, in the school was Mr. Jacob Abbott, who afterward became famous as a teacher and writer of books for children. His amiable and indulgent manner remained in the recollection of his pupil.

The promise of his life was fulfilled a little in those earliest days. Ten miles from Portland is the old Longfellow homestead at Gorham, and thither the boy was wont to go. In later life he sjjeaks of " my pleasant recollections of Gorham, the beautiful village, the elms, the farms, the pastures scented with pennyroyal, and the days of my boyhood, that have a perfume sweeter than field or flower." Here it was, perhaps, or in Deering Woods, that he had those early dreams to which he refers in the Prelude which opens his first published volume : —

" And dreams of that which cannot die,

Bright visions, came to me, As lapped in thought I used to lie, And gaze into the summer sky, Where the sailing clouds went by,

Like ships upon the sea;

" Dreams that the soul of youth engage

Ere Fancy has been quelled: Old legends of the monkish page, Traditions of the saint and sage, Tales that have the rime of age.

And chronicles of eld."

While he was still a school-boy he had begun to write and to print his poems. His first published poem was on Lo veil's Fight. His experience in the publication was recalled by him once, in a conversation with a younger poet, William Winter. He had droj^ped the manuscript with fear and trembling into the editor's box at the office of a weekly newspaper in Portland. When the next issue of the paper appeared the boy looked eagerly, but in vain, for his verses. " But I had another copy,'* he said, " and I immediately sent it to the rival weekly, and the next week it was published. I have never since had such a thrill of delight over any of my publications; " and he told how he had bought a C02)y of the paper, still damp from the press, and walked with it into a by-street of the town, where he opened it, and found his poem actually printed.

He was ready for college when he was fourteen, and his father entered him at Bowdoin, but for some reason he passed the greater part of his Freshman year at home. His college life was one which increased the expectation of his friends. One of his teachers in college, the late venerable Professor A. S. Packard, once gave his reminiscences of the poet, who entered with his brother Stephen. " He was," says Professor Packard, " an attractive youth, with auburn locks, clear, fresh, blooming complexion, and, as might be presumed, of well-bred manners and bearing."

During his college life he contributed to the periodicals of the day. The most important of these, in a literary point of view, was the United States Literary Gazette, which was published simultaneously in New York and Boston. It was founded by Theophilus Parsons. To this periodical Longfellow contributed seventeen poems; the first five included under the division Earlier Poems, in his collected writings, were among the seventeen. Fourteen of Longfellow's poems contributed to the Literary Gazette were included in a little volume published in 1826, under the title of Miscellaneous Poems selected from the United States^ Literary Gazette, and one of these was The Hymn of the Moravian Nuns, which has always remained a favorite. In 1872 a friend brought from England Coleridge's inkstand, which he gave to Mr. Longfellow, who, in acknowledging the gift, wrote : —

" This memento of the poet recalls to my recollection that Theophilus Parsons, subsequently eminent in Massachusetts jurisprudence, paid me for a dozen of my early pieces that appeared in his United States Literary Gazette with a copy of Coleridge's poems, which I still have in my possession. Mr. Bryant contributed the Forest Hymn, The Old Man's Funeral, and many other poems to the same periodical, and thought he was well paid by receiving two dollars apiece ; a price, by the way, which he himself placed upon the poems, and at least double the amount of my

honorarium. Truly, times have changed with us litth'atears during the last half century."

Longfellow graduated second in his class, and the class was one having a number of men of singular ability. It would have been a great class in any college which held Longfellow and Hawthorne, but this had also George B. Cheever and Jonathan Cilley, a young man of great promise, who died in early manhood, and John S. C. Abbott. Fifty years after graduation the surviving members met at Brunswick, and Longfellow celebrated the occasion by his noble Morituri Salutamus.

II.

Near the close of his college course an event took place in the order of academic life which had an interesting influence on the poet's career. The story is told by his classmate Abbott: " Mr. Longfellow studied Horace with great enthusiasm. There was one of his odes which he particularly admired. He had made himself as familiar with it as if it were written in his own mother tongue, and had translated it into his own glowing verse, which rivalled in melody the diction of Horace. There was at that time residing in Brunswick a very distinguished lawyer by the name of Benjamin Orr. Being a fine classical scholar, Horace was his pocket companion, from whose pages he daily read. He was, as one of the Trustees of Bowdoin College, accustomed to attend the annual examinations of the classes in the classics. In consequence of his accurate scholarship he was greatly dreaded by the students. The ode which pleased young Henry Longfellow so much was also one of his favorites. It so happened that he called upon Longfellow to translate that ode at, I think, our Senior examination. The translation was fluent and beautiful. Mr. Orr was charmed, and eagerly inquired the name of the brilliant scholar. Soon after this the trustees of the college met to choose a professor of modern languages. Mr. Orr, whose voice was

potent In that board, said, " Why, Mr. Longfellow is your man. He is an admirable classical scholar. I have seldom heard anything more beautiful than his version of one of the most difficult odes of Horace."

The poet was but nineteen when the appointment was made, and the confidence which elder men had in him is more noticeable since the professorship to which he was called was a new one, and there were few, If any, precedents In other colleges to determine its character. At the time when the appointment came to him Longfellow was reading law in his father's office, but this was probably only incidental to his larger interest in literature. At any rate he accepted at once the offer made to him, and went to Europe to qualify himself for the position by study and travel.

He remained away three years and a half, and returned to enter upon his college duties in the fall of 1829. He had spent his time of preparation in England, France, Germany, Spain, and Italy, and had laid the foundation of that liberal knowledge of modern European literature which served him In such good stead throughout his life. His journey did more than this for him. It gave him the large background to his thoughts which served to bi-ing out clearly the deeper purposes of life. In the glowing and affectionate dedication to Longfellow by George Washington Greene of his life of his grandfather. General Greene, there Is a distinct reference to this period of the poet's life.

" Thirty-nine years ago this month of April," he writes in April, 1867, " you and I were together at Naples, wandering up and down amid the wonders of that historical city, and consciously in some things, and unconsciously In others, laying up those precious associations which are youth's best preparation for age. We were young then, with life all before us; and, in the midst of the records of a great past, our thoughts would still turn to our own future. Yet even In looking forward they caught the coloring

of that past, making things bright to our eyes which, from a purely American point of view, would have worn a different asjject. From then till now the spell of those days has been upon us.

" One day — I shall never forget it — we returned at sunset fi'om a long afternoon amid the statues and relics of the Museo Borbonico. Evening was coming on, with a sweet promise of the stars: and our minds and hearts were so full that we could not think of shutting ourselves up in our rooms, or of mingling with the crowd on the Toledo. We wanted to be alone, and yet to feel that there was life all around us. We went up to the flat roof of the house, where, as we walked, we could look down into the crowded street, and out upon the wonderful bay, and across the bay to Ischia and Capri and Sorrento, and over the house-tops and villas and vineyards to Vesuvius. • . . And over all, with a thrill like that of solemn music, fell the splendor of the Italian sunset.

" We talked and mused by turns, till the twilight deepened and the stars came forth to mingle tlieir mysterious influences with the overmastering magic of the scene. It was then that you unfolded to me your plans of life, and showed me from what ' deep cisterns' you had already learned to draw. From that day the office of literature took a new place in my thoughts. I felt its forming power as I had never felt it before, and began to look with a calm resignation upon its trials, and with true appreciation upon its rewards."

It is interesting, as one thinks of Longfellow in his youth, and again in the splendor of his age, to turn to the words with which he closes the record of his first journey: —

" My pilgrimage is ended. I have come home to rest; and recording the time i)ast, I have fulfilled these things, and written them in this book, as it would come into my mind, — for the most part, when the duties of the day were over, and the world around me was hushed in sleep. . . .

The morning watches have begun. And as I write the melancholy thought intrudes upon me, To what end is all this toil ? Of what avail these midnight vigils ? Dost thou covet fame ? Vain dreamer ! A few brief days, and what will the busy world know of thee ? " He is described at this time as '' full of the ardor excited by classical pursuits. He liad sunny locks, a fresh complexion, and clear blue eyes, with all the indications of a joyous temperament."

He entered upon his work as professor with such spirit that he began very early to draw students to Bowdoin. Two years after entering upon his new duties, he was married to Mary Storer Potter, daughter of Hon. Barrett Potter and Anne (Storer) Potter, of Portland. Judge Potter was a man of strong character, and his daughter, by the testimony of those who knew her, was both strong in her intellectual nature and of rare beauty of person. It is thought that the reference is to her in the verses Footstej^s of Angels, where the poet, seeing in a reverie the forms of departed friends, sings: —

" And with them the Being Beauteous Who unto my youth was given, More than all things else to love me, And is now a saint in heaven.

" With a slow and noiseless footstep Comes that messenger divine, Takes the vacant chair beside me, Lays her gentle hand in mme.

" And she sits and gazes at me

With those deep and tender eyes, Like the stars, so still and saint-like. Looking downward from the skies."

Mr. Longfellow held his professorship at Bowdoin for five years, and during this time put forth his first formal publications. The eai'liest book with which he had to do was Elements of French Grammar, translated from the

French of C F. L'Homond, and published in 1830. Other works, edited or translated by him, and having direct reference to his occupation as a professor of modern languages and literature, appeared during these five years. The subjects of his more purely literary productions during this period were also closely connected with his profession. He published articles in the North Am.erican Review on the Origin and Progress of the French Language, a Defence of Poetry, on the Hlstorg of the Italian Language and Dialects, on Spanish Language and Literature, on Old English Romances, and on Sjyanish Devotional and Moral Poetry. In 1833 he took tliis last essay, and attaching to it a translation of Manrique's Coj^las, and of some sonnets by Lope de Vega and others, produced a volume entitled Coplas de Manrique, which may be regarded as his first purely literary venture in book form. His name was placed on the title-page with his title as professor, and the book was publislied by Allen & Ticknor, predecessors of the jwesent publishers of his works.

Meanwhile he was beginning to make use of the abundant material which he had gathered during his European sojourn, in the form of sketches of travel and little romances drawn from legendary lore. He began in The New England Magazine, a periodical long since dead, a series of papers under the title The Schoolmaster, but discontinued them after a few numbers and used some of this material and much more in his first considerable book, Outre-Mer.

This book appeared at first with no name attached, but it was probably well known who wrote it; and when the second part appeared, shortly afterward, Professor Longfellow's name was openly connected with it. The last three chapters of The Schoolmaster were not reprinted, and the serial was not resumed, perhaps because the author preferred the more satisfactory and more dignified appearance in book form. A prior publication in a magazine was

'

LIFE AND WRITINGS. xiii

more likely to obscure a book then than now. It is not impossible that the slight concejition of a schoolmaster was reserved, also, for future use in the tale of Kavanagh.

His work as an author and that as a professor were substantially one. " He proved himself," says one of his contemporaries at Bowdoln, " a teacher who never wearied of his work, who won by his gentle grace, and commanded respect by his self-respect and his respect for his office." He assumed the duties of librarian, also, and liis work was comprehensively literary. He was twenty-six years old, and had made a positive place in literature.

ni.

In a letter dated Boston, January 5, 1835, Mr. George Ticknor, then Professor of the French and Spanish Languages and of Belles Lettres at Harvard College, wrote as follows to his friend, C. S. Daveis, of Portland: "Besides wishing you a happy New Year, I have a word to say about myself. I have substantially resigned my place at Cambridge, and Longfellow is appointed substantially to fill it. I say suhstantlallij, because he is to pass a year or more in Germany and the North of Europe, and I am to continue in the place till he returns, which wiU be in a year from next Commencement, or thereabouts."

The transfer from Bowdoin to Harvard grew out of the increasing reputation of the young professor, and in taking another journey to Europe he was carrying forward the same spirit of thorough preparation, and was completing the survey of European languages and literature, by making acquaintance with those parts unvisited in his former residence abroad. His eighteen months of travel and study Avere very productive, but they were shadowed by the death of his wife, who was taken ill at Rotterdam, and died there November 29, 1835. The record of his life during this time is partially disclosed in the pages of Hyperion., and the mournful character of its early chapters may well be

xiv HENRY WADS WORTH LONGFELLOW.

taken as echoing the temper in which he pursued his solitary studies.

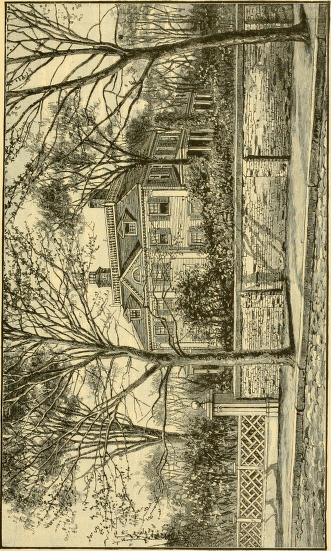

He returned to America in November, 1836, and after a short visit to his home in Portland he entered upon his new work at Cambridge. The house which is so identified with Longfellow's life was his home from the time he came to Cambridge until his death, although it was not till 1843 that he became actual owner of it. The ample, dignified mansion on Brattle Street has a generous surrounding of green fields, and a clear outlook across meadows to the winding Charles and the gentle hills beyond, but in 1836 it was even more rural in its position. The history of the house carries it back to the days of the rich Tory merchants, who were so loath to abandon the ease and dignity of the province for the anxieties and levelling of an independence of England. It was built by John Vassall in 1759, as a home for himself and his bride, who was a sister of the last royal lieutenant-governor of the province. At the outbreak of the Revolution Vassall fled to London, and the house passed into the hands of the provincial government. When soldiers flocked to Cambridge, after the Lexington and Concord fight, it was used by a battalion of Colonel John Glover's regiment of Marblehead fishermen. They held it but a short time, for upon Washington's arrival in Cambridge the house, as the most commodious in the place, was made ready for the general's headquarters. Here Washington and his military family remained during the siege of Boston.

Upon the transfer of military movements southward, Nathaniel Tracy, of Newbury port, who had grown rich by privateering, bought the estate; but his wealth vanished almost as rapidly as it was acquired, and in 1786 the place was sold to Thomas Russell, the first president of the United States Branch Bank ; and he in his turn sold it in 1792 to Andrew Craigie, who had been apothecary-general to the Continental Army, and had amassed a fortune in that

office. He became embarrassed in his affairs, and when he died his widow, who continued to live there, drew her income in part from the lease of rooms in her house to college officers and others. Mr. Sparks went there to live, and was at work upon his edition of the life and writings of Washington in the very room occupied by the general. Hither also came Dr. Edward Everett, and here lived and worked Dr. Joseph E. Worcester, the lexicographer.

The story is told that when Mr. Longfellow knocked at the door and asked the stately old lady if she would receive him as a lodger, she demurred.

" I am sorry to tell you," she said, " that I never have students to live with me."

" But I am not a student," he replied. " I am a professor in the University."

" A professor ?" She looked curiously at one so like most students in appearance.

" I am Professor Longfellow," he said.

" If you are the author of Outre-Mer, then you can come," said the old lady, and proceeded to show him her house. She led him up the broad staircase, and, proud of the historic mansion, opened one spacious room after another, only to close the door of each, saying, " You cannot have that," until at length she led him into the southeast corner room of the second story. " This was General AVashington's chamber," she said; " you may have this." And here he gladly set up his home.

Old Madam Craigie continued to live in the house until her death. On one occasion her poet lodger, entering her jDarlor in the morning, found her sitting by the open window, through which innumerable canker-worms had crawled from the trees they were devouring outside. They had fastened themselves to her dress, and hung in little writhing festoons from the white turban on her head. Her visitor, surprised and shocked, asked if he could do nothing to destroy the worms. Raising her eyes from the book which

she sat calmly reading, she said in tones of solemn rebuke, "Young man, have not our fellow-worms as good a right to live as we ? " Dr. Worcester bought the estate, and afterwai'd sold it to Mr. Longfellow.

He sjient seventeen years in Cambridge as professor, and he carried the title the rest of his days. It has not been customary of late years to associate Mr. Longfellow with academic life, but while he was engaged in it he gave himself to it with great assiduity. Under Mr. Ticknor's management, the modern languages and literature at Harvard had been erected into a department, with four foreigners for teachers, all being directed and supervised by the jirofessor in charge. Something of the nature of this department jilan, which was an innovation upon the customary college method, may be gathered from the letter of Mr. Ticknor already quoted, in which he announced the election of Mr. Longfellow. " Within the limits of the department," he writes, "I have entirely broken up the division of classes, established fully the principle and practice of progress accox-ding to proficiency, and introduced a system of voluntary study, which for several years has embraced from one hundred and forty to one hundred and sixty students; so that we have relied hardly at all on college discipline, as it is called, but almost entirely on the good dispositions of the young men and their desire to learn."

The traditions of this department were carried forward by Mr. Longfellow, as may be seen by an animated letter of reminiscences, written in 1881 by Rev. Edward Everett Hale, who was one of his students : —

" I was so fortunate as to be in the first ' section,' which Mr. Longfellow instructed personally when he came to Cambridge in 1836. Perhaps I best illustrate the method of his instruction when I say that I think every man in that section would now say that he was on intimate terms with Mr. Longfellow. We are all near sixty now, but I think that

every one of the section would expect to have Mr. Longfellow^ recognize him, and would enter into familiar talk with him if they met. From the first he chose to take with us the relation of a personal friend a few years older than we were.

" As it happened, the regular recitation rooms of the college were all in use, and indeed I think he was hardly expected to teach any language at all. He was to oversee the department and to lecture. But he seemed to teach us German for the love of it; I know I thought he did, and till now it never occurred to me to ask whether it were a part of his regular duty. Any way, we did not meet him in one of the rather dingy ' recitation rooms,' but in a sort of pai'lor. carpeted, hung with pictures, and otherwise handsomely furnished, which was, I believe, called ' the Corporation Room.' We sat round a mahogany table, which was reported to be meant for the dinners of the trustees, and the whole affair had the aspect of a friendly gathering in a private house, in which the study of German was the amusement of the occasion. These accidental surroundings of the place characterize well enough the whole proceeding.

" He began with familiar ballads, read them to us, and made us read them to him. Of course we soon committed them to memory without meaning to, and I think this was probably part of his theory. At the same time we were learning the paradigms by rote. But we never studied the grammar except to learn them, nor do I know to this hour what are the contents of half the pages in the regular German grammars.

" This was quite too good to last; for his regular duty was the oversight of five or more instructors, who were teaching French, German, Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese to two or three hundred undergraduates. All these gentlemen were of European birth, and you know how undergraduates are apt to fare with such men. Mr. Longfellow had a real administration of the whole department. His

title was ' Smith Professor of Modern Literature,' but we always called him ' the Head,' because he was head of the department. We never knew when he might look in on a recitation and virtually conduct it. We were delighted to liave him come. 'Any slipshod work of some poor wretch from France, who was tormented by wild-cat Sophomores, would be made straight and decorous and all right. We all knew he was a poet, and were proud to have him in the college, but at the same time we resjjected him as a man of affairs.

" Besides this, he lectured on authors or more general subjects. I think attendance was voluntary, but I know we never missed a lecture. I have full notes of his lectures on Dante's Dlvina Coviviedia, which confirm my recollections, namely, that he read the whole to us in English, and explained whatever he thought needed comment. I have often referred to these notes since. And though I suppose he included all that he thought worth while in his notes to his translation of Dante, I know that until that was published I could find no such reservoir of comment on the poem."

Another of his jjupils, T. W. Higginson, in recalling the days of Longfellow's professorship, writes : " In respect of courtesy his manners quite anticipated the present time, and were a marked advance upon the merely pedagogical relation which then prevailed. He was one of the few professors who then addressed his pupils as ' Mr.; ' his tone to them, though not paternal or brotherly, was always gentlemanly. On one occasion, during an abortive movement towai'd rebellion, some of the elder professors tried in vain to obtain a hearing from a crowd of angry students collected in the college yard ; but when Longfellow spoke, there was a hush, and the word went round, 'Let us hear Professor Longfellow, for he always treats us as gentlemen.' As an instructor he was clear, suggestive, and encouraging; his lectures on the great French writers were admirable, and his facility in equivalent phrases was of great use to

his jiupils and elevated their standai'd of translation. He was scrupulously faithful to his duties, and even went through the exhausting process of marking French exercises with exemplary patience. Besides his own classes in Moliere, Racine, and other poets, he had the general supei'vision of his department, which inclucled subordinate teachers in French, Spanish, Italian, and German. All these were under his authority, and he doubtless had the selection of all appointees. There was probably no coUege in the United States which had so large a corps of instructors in the modern languages as had Harvard at that time."

With the regular, methodical habits indicated in the foregoing reminiscences, the professor found place for the litterateur and poet. Contributions to the North American " were continued," and it is to be noted that one of these was a hearty recognition of Hawthorne's Twice - Told Tales, which appeared in 1837, and needed at the time all the encouragement which appreciative minds could give. How much pleasure it gave to Hawthoi'ne may be read in the letter which the story-teller was moved to write to the critic : —

Salem, June 19, 1837.

Dear Longfellow, — I have to-day received and read with huge delight your review of Hawthorne's Tivice-Told Tales. I frankly own that I was not without hopes that you would do this kind office for the book ; though I could not have anticipated how very kindly it would be done. Whether or no the public will agree to the praise which you bestow on uie, there are at least five persons who think you the most sagacious critic on earth, namely, my motlier and two sisters, my old maiden aunt, and finally the strongest believer of the whole five, my own self. If I doubt the sincerity and correctness of any of my critics, it shall be of those who censure me. Hard would be the lot of a poor scribbler, if he may not have this privilege. . . . Very sincerely yours,

Nath. Hawthorne.

Other papers of this period were articles on Teg tier's

Frith iof's Saga and Anglo-Saxo7i Literature, indicative of his scholastic work.

IV.

As Outre-Mer was. in some ways the report of his first journey to Europe, so Hyperion stands as expressive of his second. Outre-Mer is a record of travel, continuous in its geographical outline, but separated from ordinary itineraries by noting less the personal accidents of the traveller than the poetic and romantic scenes which, whether of the present or the past, marked the journey and transformed it into the pilgrimage of a devotee to art. In Hyperion a more deliberate romance is intended, but the lights and shades of the story are heightened or deepened by the passages of travel and study, which form the background from which the human figures are relieved. It is interesting to observe how, as the writer was more withdrawn from the actual Europe of his eyes, he used the Europe of his memory and imagination to wait upon the movements of a profounder study, the adventures of a human soul. These two books and the occasional critical papers are characterized by a strong consciousness of literary art. Life seems always to suggest a book or a picture, and nature is always viewed in its immediate relation to form and color. There is a singular discovery of the Old World, and while European writers like Chateaubriand, for example, were turning to America for new and unworn images, Longfellow, reflecting the awaking desire for the enduring forms of art which his countrymen were showing, eagerly disclosed the treasures to which the owners seemed almost indifferent. It is difficult to measure the influence which his broad, catholic taste and his refined choice of subjects have had upon American culture through the medium of these works, and that large body of his poetry which draws an inspiration from foreign life.

Hyjjerion at once became a general favorite. Barry Cornwall is said to have read it through once a year for the sake of its style. It is so faithful in its descriptions that it still serves as a companion to travellers on the Rhine, and is read at Heidelberg and elsewhei'e somewhat as Byron used to be read in Switzerland and Italy. It contains some translations also of German verse, which by their musical form obtained at once a popularity aside from the prose romance.

The same year, 1839, which saw the publication of Hyperion saw also the appearance of Longfellow's first volume given wholly to verse, a thin book entitled Voices of the Night. He had been contributing poems from time to time to the Knickerbocker Magazine, and he now collected these, some of the earlier poems contributed to the United States Literary Gazette, the poetry in the volume of Coplas de Manrique, the verses contained in Hypterion, and other translations. The most famous poem in this collection was the Psalm of Life. It was written, we are told by Mr. Fields, on a bright summer morning in July, 1838, as the poet sat at a small table between two windows, in the corner of his chamber. He kept it unpublished for some time, since it had a very close connection in his own mind with the troubles through which he had lately passed.

In 1841 the next volume of poems was issued, under the title of Ballads and other Poems, — a title still preserved in a division of his collected poems. It may be said to contain more of his famous short poems than any other volume which he issued, for it opens with The Skeleton in Armor ; it holds The Wreck of the Hesperus, The Village Bldcks7mtJi, The Rainy Day, To the River Charles, Maidenhood, and Excelsior. In the notes to his poems Mr. Longfellow has himself related the slight incidents which led to the writing of The Skeleton in Armor.

A letter from Mr. Longfellow to Mr. Charles Lanman

gives an interesting account of the circumstances attending the production of The Wreck of the Hesperus : —

Cambridgk, November 24, 1871.

My dear Sir, — Last night I had the pleasure of receiving your friendly letter and the beautiful pictures that came with it, and I thank you cordially for the welcome gift and the kind remembrance that prompted it. They are both very interesting to me ; pax'ticularly the Keef of Norman's Woe. What you say of the ballad is also very gratifying, and induces me to send yon in return a bit of autobiography.

Looking over a journal for 1839, a few days ago, I found the following entries : —

" December 17. — News of shipwrecks, horrible, on the coast. Forty bodies washed ashore near Gloucester. One woman lashed to a piece of wreck. There is a reef called Norman's Woe, where many of these took place. Among others the schooner Hesperus. Also, the Seaflower, on Black Rock. I will write a ballad on this.

" December 30. — Wrote last evening a notice of Allston's poems, after which sat till 1 o'clock by the fire, smoking ; when suddenly it came into my head to write the Ballad of the Schooner Hesperus, which I accordingly did. Then went to bed, but could not sleep. New thoughts were running in my mind, and I got up to add them to the Ballad. It was 3 by the clock."

All this is of no importance but to myself. However, I like sometimes to recall the circumstances under which a poem was written, and as you express a liking for this one it may perhaps interest you to know why and when and how it came into existence. I had quite forgotten about its first publication ; but I find a letter from Park Benjamin, dated January 7, 1840, beginning (you will recognize his style) as follows : —

" Your ballad. The Wreck of The Hesperus, is grand. Inclosed are twenty-five dollars (the sum you mentioned) for it, paid by the proprietors of ' The New Worixl,' in which glorious paper it will resplendently coruscate on Saturday next."

Pardon this gossip, and believe me, with renewed thanks, yours faithfully,

Henry W. Longfellow.

The word excelsior happened to catch his eye one evening as he was reading a bit of newspaper, and his mind began to kindle over the suggestion of the word. He took the nearest scrap of paper, which happened to be a letter from Charles Sumner, and wrote the verses with corrections on the back. The scrap is still preserved and shown at the library of Harvard University. A pretty story is told of the fortunes of one of the poems in the volume, the well-known Maidenhood. Once when it was printed in an illustrated paper, it fell into the hands of a poor woman living in a lonely cabin in a sterile portion of the Northwest. She had papered the walls of her cabin with the journals which a friend had sent her, and this poem with its picture was upon the wall by her table. Here, as slie stood at her bread-making or ironing, day after day, she gazed at the picture and read the poem until, by long brooding over it, she understood it and absorbed it as people rarely possess the words they read. The friend who sent her the papers was himself a man of letters, and coming afterward to see her in her loneliness, stood amazed and humbled as she talked to him artlessly about the poem, and disclosed the depths of her intelligence of its beauty and thought.

In 1842 he paid a third visit to Europe. It was on his return voyage in October that he wrote the Poems on Slavery which made his next volume, and formed his conti'ibution to the discussion which was then engrossing so much of the thought of the country.

In July, 1843, he married Miss Fanny Appleton, daughter of the late Nathan Appleton, of Boston, a lady of noble bearing, of great beauty of person and dignity of character, whom he had met on his recent journey in Europe. By her he had two sons and three daughters. Mrs. Longfellow died July 9, 1861, under circumstances which caused a terrible shock. She had been amusing her children with some seals which she made, when some of the burning wax fell upon her light summer dress, and

before help could be given she had received severe burns, from which she died in a few hours. The shock to the poet was so great that for a time it seemed as if reason itself was in danger; but the firmness and calmness of his nature reasserted itself, and he slowly came back to his singing. His friends were wont to obsei've, however, his increased signs of age and the greater silence of his life. " I have never heard him make but one allusion to the great grief of his life," said an intimate friend. " We were speaking of Schiller's fine poem, ' The Ring of Polycrates.' He said, ' It was just so with me. I was too happy. I might fancy the gods envied me, if I could fancy heathen gods.' "

To return to his publications in the order of their appearance. The Spanish Student came out in 1843, and in 1845 he edited a little collection of jioems called The Waif. In the same year, also, he made the important collection known as The Poets and Poetry of Europe^ containing biographical and critical sketches, with translations by various English poets, his own contribution being considerable. In 1846 appeared The Belfry of Bruges and other Poems, and the next year came Evangeline.

Two years later, in 1849, appeared Mr. Longfellow's latest prose work, Kavanagh, a tale of New England life, and in 1850 a new volume of poems, entitled The Seaside and the Fireside. The dedication of this volume, addressed to no one name, is a graceful acknowledgment of the multitudinous responses which he was now receiving. " Thanks," he says, —

" Thanks for the sympathies that ye have shown ! Thanks for each kindly word, each silent token, That teaches me, when seeming most alone,

Friends are around us, though no word be spoken.

" Kind messages, that pass from land to land ;

Kind letters, that betray the heart's deej) history, In which we feel the pressure of a hand, —

One touch of fire, — and all the rest is mystery!"

And the Dedication closes with words which had a truly prophetic meaning: —

" Therefore I hope, as no unwelcome guest,

At your warm fireside, when tlie lamps are lighted, To have my place reserved among the rest, Nor stand as one unsought and uninvited!''

The longest poem in the collection was The Building of the Ship, —" that admirably constructed poem," as Dr. Holmes says, " beginning with the literal description, passing into the higher region of sentiment by the most natural of transitions, and ending with the noble climax,

" ' Thou too sail on, 0 Ship of State,'

which has become the classical expression of patriotic emotion." It would be curious if it should prove that the ode of Horace, the translation of which led to Mr. Longfellow's appointment to a professorship at Bowdoin, was that one beginning —

" 0 navis referent in mare te novi,"

which the poet so nobly repeated in higher sti'ains at the close of The Building of the Ship. Mr. Noah Brooks, in a paper on " Lincoln's Imagination," which he contributed to Scribner's Monthly (August, 1879), mentions that he found the President one day attracted by these closing stanzas, which were quoted in a political speech. " Knowing the whole poem," he adds, " as one of my early exercises in recitation, I began, at his request, with the description of the launch of the ship, and repeated it to the end. As he listened to the last lines, —

" ' Our hearts, our hopes, are all with thee, Our hearts, our hopes, our prayers, our tears. Our faith triumphant o'er our fears, Are all with thee, — are all with thee !'

his eyes filled with tears, and his cheeks were wet. He did not speak for some minutes, but finally said with sim

plicity, ' It is a wonderful gift to be able to stir men like that.' "

The critics had complained of the European flavor of Mr. Longfellow's verse. He was steadily keeping on his way, however, expressing his nature honestly, and finding a noble delivery in such national poems as The Buildiiig of the ShijJ.

It is noticeable how^ much more fully the tide of his poetry set in the direction of America after the publication of Evangeline; while The Golden Legend was published in 1851, and is perhaps the most perfect expression of the Old World in his verse. The Song of Hiawatha appeared in 1855, and awakened an enthusiasm which was unexampled in the history of his literary career.

The story is told that in the summer of 1857 acting Governor Stanton, of Kansas, paid a visit to the citizens of Lawrence, in that State. After partaking of the hospitalities shown him by Governor Robinson, he addressed, by request, a crowd of some five hundred free-state men, who did not hesitate to manifest their disapprobation at such portions of his speech as did not accord with their peculiar political views. At the close of his speech Mr. Stanton pictured in glowing language the Indian tradition of Hiawatha, of the " peace pipe" shaped and fashioned by Gitche Manito, and by which he called tribes of men together, closing with the lines, —

" I am weary of your quarrels, Weary of your wars and bloodshed, Weary of your prayers for vengeance, Of your wrangliug-s and dissensions ; All your strengtli is in your union, All your danger is in discord ; Therefore be at peace henceforward, And as brothers live together."

The aptness of the quotation from so favorite a poem acted

like a charm for the time in pacifying the crowd, who applauded vociferously.

Innumerable discussions arose over the faithfulness of the poem to Indian traditions, but the most renowned Indian scholars supported the claims of the poem to truthfulness, and the liquid names passed at once into common use. It may fairly be said that by this work a popularity was given to Indian names which did much to preserve them from disuse as titles to rivers, mountains, and districts.

The Courtship of Miles Standish appeared in 1858, and the volume bearing this title contained also a number of short poems, under the collective title Birds of Passage. The Atlantic Monthly had been established the year befoi-e, and in the first number Mr. Longfellow published his jioem Santa Filomena. He became a very frequent contributor, and some of the poems in this volume were those which had thus far appeared in The Atlantic. Indeed, after this date, his smaller volumes of original verse were for the most part collections from time to time of poenis which were first printed in that magazine. In the following year the poet received the degree of Doctor of Laws from Harvard.

In the fall of 1863 was published Tales of a TVayside Inn, with a few poems added under the title Birds of Passage, Flight the Second. The Tales constitute the division known as the First Day, for the volume as now published contains also two other parts. The Prelude to this first part, introducing the characters who share in the festivities of the Inn, has always been a favorite," and the several personages have been identified with more or less confidence, the Inn itself being the old Howe Tavern, which still stands by the turnpike which runs through Sudbury, in Massachusetts: the landlord is easily said to stand for Lyman Howe; the theologian for Professor Treadwell, the pliysicist, who was also an unprofessional student of theol

ogy; the poet for T. W. Parsons, the musician for Ole Bull, the student for Heniy Wales, and the Sicilian for Luigi Monti. The original, if there was one, of the Spanish Jew is not known.

Flower-de-Luce was the title of a small volume of poems published in 1867, and the same year appeared the first of the three volumes containing the poet's translation of Dante, a work which was completed by the press in 1872. One of his friends states that his translation of the Inferno " was the result of ten minutes' daily work at a standing desk in his library, while his coffee was reaching the boiling point on his breakfast table." As he was an orderly man, and like all highly organized natures set a high value on time, this may well have been; but the final result was obtained only after a long and careful consideration, in which the poet invited the aid of Mr. Lowell, Professor Norton, Mr. Howells, and other Italian scholars, who met with him in a little club for the discussion of the work.

In May, 1868, Mr. Longfellow again visited Europe with his, family, and, going now with the accumulating honors of his eminent career, his presence was the occasion there of marked homage. Esjiecially was this true in England, where he received abundant social and civic honors. The University of Cambridge conferred on him the degree of Doctor of Laws, and Oxford gave him the title of Doctor of Civil Law the next year. An English reporter describes him as he appeared at Cambridge in the scarlet robes of an academic dignitary : —

" The face was one which, I think, would have caught the spectator's glance even if his attention had not been called to it by the cheers which greeted Longfellow's appearance in the robes of an LL. D. Long white silken hair and a beard of patriarchal length and whiteness inclosed a young, fresh-colored countenance, with fine-cut features and deepsunken eyes, overshadowed by massive black eyebrows. Looking at him, you had the feeling that the white head of

hair and beard were a mask put on to conceal a young man's face; and that if the poet chose he could throw off the disguise, and appear as a man in the jjrime and bloom of life."

VI.

Mr. Longfellow returned to his home in the fall of 1869. During his absence The New England Tragedies had been published, and in 1872 came out The Divine Tragedy. At the same time the poet published his Christies, which consists of The Divine Tragedy, The Golden Legend, and The Neiv England Tragedies, as a consecutive trilogy, and it is to be regarded as the poet's most serious and profound undertaking. In the same year appeared also Three Books of Song, which contained the Second Day of Tales of a Wayside Inn, Judas Maccabceus, and a number of translations. In 1874 was published Aftermath, which comprised the completion of Tales of a Wayside Inn and the Third Flight of Birds of Passage. The Masque of Pandora and other poems followed in 1875.

This volume contained the poem Morituri Salutamus, read by the poet at the gathering of his classmates upon the fiftieth anniversary of graduation at Bowdoin. The occasion was one of singular interest, and the fact that the poet had never publicly recited one of his poems except in the case of the Phi Beta Kappa poem at Harvard in 1833, gave a special value to the services in the plain church building at Brunswick. He expressed his relief when he found that he could read his poem from the pulpit, for, as he said, " Let me cover myself as much as possible; I wish it might be entirely." In the same volume was The Hanging of the Crane, the delightful domestic poem which had been previously issued with abundant illustrations the year before, after it had been first printed in The New York Ledger, the poet receiving for its publication there the unprecedented sum of four thousand dollars. The

Masque of Pandora was adapted for the stage and set to music by Alfred Cellier, and brought out at the Boston Theatre in 1881.

Shortly after the publication of this volume there began to appear a series of volumes, edited by Mr. Longfellow, entitled Poems of Places, which were published at intervals during the next four years, and extended to thirty-one volumes; the woi'k of sifting and arranging these poems gave him an agreeable occupation, for he was always at home in the best poetry of the world. While the series was in progress he issued, in 1878, Keratnos a7id other Poems, which gathered up the poems which he had been publishing the past three yeai'S. It is noticeable that in these later volumes the sonnet held a conspicuous place. Among these is the touching one entitled A Navieless Grave, of which the origin is told by Mrs. Apphia Howard: —

" I found in 1864, on a torn scrap of the Boston Sat^irday Evening Gazette, a description of a burying - ground in Newport News, where on the head-board of a soldier might be read the words ' A Union Soldier mustered out,' and this was the only inscription. The correspondent told the brief story very effectively, and, knowing Mr. Longfellow's intense patriotism and devotion to the Union, I thought it would impress him greatly. I knew also that the account would seem vital to him from the fact that his own son Charles was a Union soldier and severely wounded during the war.

" After carefully pasting the broken bits together on a bit of cardboard I sent it to Mr. Longfellow by Mr. [G. W.] Greene, who did not think Longfellow would use it, for he declared ' a poet could not write to order.' In a few days Mr. LongfelloAv acknowledged it by a letter, which I did not at all expect, as follows : —

"' In the writing of letters, moi'e, perhaps, than in anything else, Shakespeare's words are true ; and

' " The flighty purpose never is o'ertook Unless the deed go with it."

For this reason, the touching incident you have sent me has not yet shaped itself poetically in my mind, as I hope it some day will. Meanwhile, I thank you most sincerely for bringing it to my notice, and I agree with you in thinking it very beautiful.' " It was ten years and more before the sonnet was printed ; how long it may have lain in the poet's drawer we do not know.

The last published volume was Ultima Thule, issued in 1880, and containing a few melodious verses. A singular interest attaches to the volume. It is dedicated to his lifelong friend George Washington Greene, whose tender dedication to the poet of his life of his grandfather disclosed a little of the poet's inner life also. It touches upon the friendships of the jioet, that for Bayard Taylor and for the poet Dana, and it contains the lines Frdvi my Arm-Chair., which have set a precious seal upon the poet's relation to childhood. The origin of the poem is well known, but deserves to be repeated. The poem The Village Blacksm/lth had been a great favorite, and visitors to Cambridge did not fail to seek the spreading chestnut under which the smithy once stood. The smithy disappeared several years ago ; but the tree remained until 1876, when the city government, with a prudent zeal which no remonstrance of the poet and his friends could divert, ordered it to be cut down, on the plea that its low branches endangered drivers upon high loads passing upon the road beneath it.

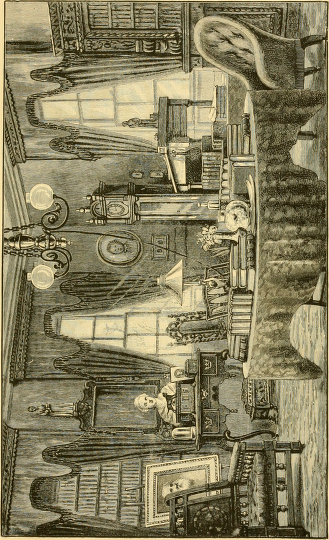

The after-thought came to construct some memento of the tree for the poet, and the result was the presentation, upon the poet's seventy-second birthday, by the children of Cambridge, of a chair made from the wood of the tree. The' color is a dead black, the effect being produced by ebonizing the wood. The upholstering of the arms and the cushion is in green leather. The casters are glass balls set in sockets. In the back of the chair is a circular piece of

carving, consisting of hoi-se-chestnut leaves and blossoms. Horse-chestnut leaves and burrs are presented in varied combinations at other points. Underneath the cushion is a brass j^late, on which is the following inscription : —

To

The Author

of

The Village Blacksmith

This chair, made from the wood of the

spreading chestuut-tree,

is presented as

An expression of gratefid regard and veneration

by

The Children of Cambridge,

who with their friends join in best wishes

and congratulations

on

This Anniversary,

February 27, 1879.

Around the seat, in raised German text, are the lines from the poem, —

" And children coming home from school Look in at the open door; And catch the burning sparks that fly Like chaff from a threshing floor."

The poem From viy Arm-Chair was the poet's response to the gift. In 1880, when the city of Cambridge celebrated the two hundred and fiftieth anniversary of the founding of the town, December 28th, there was a children's festival in the morning at Sanders Theatre, and the chair stood ])rominently on the platform, where the thousand school-children gathered could see it. The poem was read to them by Mr. Riddle, and, better than all, the poet himself came forward, to the surprise of all who knew how absolute was his silence on public occasions, and standing,

the picture of beautiful old age, he spoke smilingly these few words to the delighted childi-en : —

My dear Young Friends, — I do not rise to make an address to you, but to excuse myself from making one. I know the proverb says that he who excuses himself accuses himself, and I am willing on this occasion to accuse myself, for I feel very much as I suppose some of you do when you are suddenly called upon in your class-room, and are obliged to say that you are not prepared. I am glad to see your faces and to hear your voices. I am glad to have this opportunity of thanking you in prose, as I have already done in verse, for the beautiful present you made me some two years ago. Perhaps some of you have forgotten it, but I have not ; and I am afraid — yes, I am afraid — that fifty years hence, when you celebrate the three hundredth anniversary of this occasion, this day and all that belongs to it will have passed from your memory ; for an English philosopher has said that the ideas as well as children of our youth often die before us, and our minds represent to us tliose tombs to which we are approacliing, where, though the brass and marble remain, yet the inscriptions are effaced by time, and the imagery moulders away.

The chair gave the children a proud feeling of proprietorshiji in the poet, and hundreds of little boys and girls presented themselves at the door of the famous house. None were ever turned away, and pleasant memories will linger in the minds of those who boldly asked for the poet's hospitality, unconscious of the tax which they laid upon him. A pleasant story is told by Luigi Monti, who had for many years been in the habit of dining with the poet every Saturday. One Christmas, as he was walking toward the house, he was accosted by^ a girl about twelve years old, who inquired where Mr. Longfellow lived. He told her it was some distance down the street, but if she would walk along with him he would show her. When they reached the gate, she said, —

" Do you think I can go into the yard ? "

" Oh, yes," said Signor Monti. " Do you see the room

on the left ? That is where Martha Washington held her receptions a hundred years ago. If you look at the windows on the right you will probably see a white-haired gentleman reading a i)aper. Well, that will be Mr. Longfellow."

The child looked gratified and happy at the unexpected pleasure of really seeing the man whose poems she said she loved. As Signer Monti drew near the house he saw Mr. Longfellow standing with his back against the window, his head out of sight. When he went in, the kind-hearted Italian said, —

" Do look out of the window and bow to that little girl, who wants to see you very much."

" A little girl wants to see me very much ? Where is she ? " He hastened to the door, and, beckoning with his hand, called out, " Come here, little girl; come here, if you want to see me." She came forward, and he took her hand and asked her name. Then he kindly led her into the house, showed her the old clock on the stairs, the children's chair, and the various souvenirs which he had gathered. This was but one little instance of many.

Indeed, it was not to children alone that he was kind. Numberless were the acts of courtesy which he showed not to the courteous only, but to those whom others would have turned away. " Bores of all nations," says INIr. Norton, " especially of our own, persecuted him. His long-suffering ])atience was a wonder to his friends. It was, in truth, the sweetest charity. No man was ever before so kind to these moral mendicants. One day I ventured to remonstrate with him on his endurance of the persecutions of one of the worst of the class, who to lack of modesty added lack of honesty, — a wretched creature, — and when I had done he looked at me with a pleasant, reproving, humorous glance, and said, ' Charles, who would be kind to him if I were not ? ' It was enough."

" I happened," says a writer, " to be often brought into

LIFE AND WRITINGS. xxxv

contact with a very intelligent but cynical and discontented laboring man, who never lost an opportunity of railing against the rich. To such men wealth and poverty are the only distinctions in life. In one of his denunciations I heard him say, ' I will make an exception of one rich man, and that is Mr. Longfellow. You have no idea how much the laboring men of Cambridge think of him. There is many and many a family that gets a load of coal from Mr. Longfellow, without anybody knowing where it comes from.' . . . The people of Cambridge delighted in Mr. Longfellow's loyalty to the town of his residence and its society. They could not fail to be gratified that he and his family did not seek the society of the neighboring metropolis, or rather usually declined its solicitations, and preferred the simjjle and familiar ways and old friends of the less pretentious suburban community. Nothing could be more charming than tlie apparently absolute unconsciousness of distinction which pervaded the intercourse of Mr. Longfellow and his family with Cambridge society."

The title of Ultima Thule was a tacit confession that the poet had reached the border of earth, but the last poem in the volume. The Poet and his Sonz/s, was a truer confession that the singer must sing when the songs come to him ; and thus from time to time, in the last year of his life, Mr. Longfellow uttered his poems, reading the proof, indeed, of one, Mad River, but a few days before his death, the poem appearing in the May number of The Atlaiitic.

As the seventy-fifth anniversary of the poet's birth drew near, there was a spontaneous movement throughout the country looking to the celebration of the day, especially among the school-children. The recitation of his poems by thousands of childish voices was the happiest possible form of honoring him. In his own city of Cambridge all the schools thus remembered him, and numberless schools in the "West and South also took the same form of celebration ; while the Historical Society which had its home in hia

XXXvi HENRY WADSWORTH LONGFELLOW,

birthplace held a meeting, and its members gave themselves up to pleasant reminiscences of the poet.

He had been confined to the house for several weeks before his last sickness, but in the warm days of early spring had ventured upon his veranda. A neighbor recalls the pretty sight of the gray-haired poet playing with his little grandchild one day in March. It was not until Monday, March 20th, that the fatal illness caused serious alarm ; and on Friday, the 24th, the bells tolled his death. His neighbors and the whole community showed their solicitude in those few days. The very children were heard to say, as they passed his gate, " We must tread gently, for Mr. Longfellow is very sick." The message of his death was sent round the world, and probably not a journal in Christendom but had some words, few or many, in regret and honor, upon receipt of the news. On Sunday, March 2C, 1882, he was buried from his home, where his family and a few of his nearest friends were gathered. He was laid in Mount Auburn Cemetery, in Cambridge; and that afternoon Appleton Chapel, of Harvard University, was opened for a simple memorial service, thronged by a silent multitude, who listened to the tender discourse of two of the college clergy, to the hymns of the college choir, and to the consolation of the sacred Scriptures.

1.0NGFELL0W IN HOME LIFE.

BY ALICE M. LONGFELLOW.

Many people are full of poetry without, perhaps, recognizing it, because they have no power of expression. Some have, unfortunately, full power of expression, with no depth or richness of thought or character behind it. With Mr. Longfellow, there was complete unity and harmony between his life and character and the outward manifestation of this in his poetry. It was not worked out from his brain, but was the blossoming of his inward life.

His nature was thoroughly poetic and rhythmical, full of delicate fancies and thoughts. Even the ordinary details of existence were invested with charm and thoughtfulness. There was really no line of demarcation between his life and his poetry. One blended into the other, and his daily life was poetry in its truest sense. The rhythmical quality showed itself in an exact order and method, running through every detail. This was not the precision of a martinet; but anything out of place distressed him, as did a faulty rhyme or defective metre.

His library was carefully arranged by subjects, and, altliough no catalogue was ever made, he was never at a loss where to look for any needed volume. His books were deeply beloved and tenderly handled. Beautiful bindings were a great delight, and the leaves were cut with the utmost care and neatness. Letters and bills were kept in the same orderly manner. The latter were paid as soon as rendered, and he always personally attended to those in Die Tieighborhood. An unpaid bill weighed on him like a night

mare. Letters were answered day by day, as they accumulated, although it became often a weary task. He never failed, I think, to keep his account books accurately, and he also used to keep the bank books of the servants in his employment, and to lielp them with their accounts.

Consideration and thoughtfulness for others were strong characteristics with Mr. Longfellow. He, indeed, carried it too far, and became almost a prey to those he used to call the " total strangers," whose demands for time and help were constant. Fortunately he was able to extract much interest and entertainment from the different types of humanity that were always coming on one pretext or another, and his genuine sympathy and quick sense of humor saved the situation from becoming too wearing. This constant drain was, however, very great. His unselfishness and courtesy prevented him from showing the weariness of spu"it he often felt, and many valuable hours were taken out of his life by those with no claim, and no appreciation of what they were doing.

In addition to the " total strangers " was a long line of applicants for aid of every kind. " His house was known to all the vagrant train," and to all he was equally genial and kind. There was no change of voice or manner in talking with the humblest member of society ; and I am inclined to think the friendly chat in Italian with the organgrinder and the little old woman peddler, or the discussions with the old Irish gardener, were quite as full of pleasure as more important conversations with travelers from Elurope.

One habit Mr. Longfellow always kept up. Whenever he saw in a newspaper any pleasant notice of friends or acquaintances, a review of a book, or a subject in which they were interested, he cut it out, and kept the scraps in an envelope addressed to the person, and mailed them when several had accumulated.

He was a great foe to procrastination, and believed in attending to everything without delay. In connection with

HOME LIFE. xxxix

this I may say, that when he accepted the invitation of his classmates to deliver a poem at Bowdoin College on the fiftieth anniversary of their graduation, he at once devoted himself to the work, and the poem was finished several months before the time. During these months he was ill with severe neuralgia, and if it had not been for this habit of early preparation tlie j)oem would probably never have been written or delivered.

Society and hospitality meant something quite real to Mr. Longfellow. I cannot remember that there were ever any formal or obligatory occasions of entertainment. All who came were made welcome without any special preparation, and without any thought of personal inconvenience.

Mr. Longfellow's knowledge of foreign languages brought to him travelers from every country, — not only literary men, but public men and women of every kind, and, during the stormy days of European jjolitics, great numbers of foreign patriots exiled for their liberal opinions. As one Englishman pleasantly remarked, " There are no ruins in your country to see, Mr. Longfellow, and so we thought we would come to see you."

Mr. Longfellow was a true lover of peace in every way, and held war in absolute abhorrence, as well as the taking of life in any form. He was strongly opposed to capital punishment, and was filled with indignation at the idea of men finding sport in hunting and killing dumb animals. At the same time he was quickly stirred by any story of wrong and oppression, and ready to give a full measure of help and sympathy to any one struggling for freedom and liberty of thought and action.

With political life, as such, Mr. Longfellow was not in full sympathy, in spite of his life-long friendship with Charles Sumner. That is to say, the principles involved deeply interested him, but the methods displeased him. He felt that the intense absorption in one line of thought prevented a full development, and was an enemy to many of

xl HENRY WADS WORTH LONGFELLOW.

the most beautiful and important things in life. He considered that his part was to cast his weight with what seemed to him the best elements in public life, and he never omitted the duty of expressing his ojiinion by his vote. He always went to the polls the first thing in the morning on election day, and let nothing interfere with this. He used to say laughingly that he still belonged to the Federalists.

Mr. Longfellow came to Cambridge to live in 1837, when he was thirty years old. He was at that time professor of literature in Harvard College, and occupied two rooms in the old house then owned by the widow Craigie, formerly Washington's Headcpiarters. In this same old house he passed the remainder of his life, being absent only one year in foreign travel. Home had great attractions for him. He cared more for the quiet and repose, the comjjanionsliip of his friends and books, than for the fatigues and adventures of new scenes. Many of the friends of his youth were the friends of old age, and to them his house was always open with a warm welcome.

Mr. Longfellow was always full of reserve, and never talked much about himself or his work, even to his family. Sometimes a volume would appear in print, without his having mentioned its preparation. In spite of his general interest in people, only a few came really close to his life. With these he was always glad to go over the early days passed together, and to consult with them about literary work.

The lines descriptive of the Student in the Wayside Inn might apply to Mr. Longfellow as well: —

" A youth was there, of qiiiet ways, A Student of old books and days. To whom all tongues and lands were known, And yet a lover of his own; With many a social virtue graced. And yet a friend of solitude; A man of such a genial mood The heart of all things he emhraced, And yet of such fastidious taste, He never found the best too good."

EVANGELINE: A TALE OF ACADIE.

HISTORICAL INTRODUCTION.

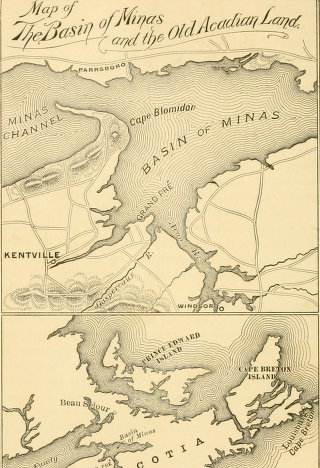

The country now known as Nova Scotia, and called formerly Acadie by the French, was in the hands of the French and English by turns until the year 1713, when, by the Peace of Utrecht, it was ceded by France to Great Britain, and has ever since remained in the possession of the English. But in 1713 the inhabitants of the peninsula were mostly French farmers and fishermen, living about Minas Basin and on Annapolis River, and the English government exercised only a nominal control over them. It was not till 1749 that the English themselves began to make settlements in the country, and that year they laid the foundations of the town of Halifax. A jealousy soon sprang uj) between the English and French settlers, which was deepened by the great conflict which was impending between the two mother countries ; for the treaty of peace at Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748, which confirmed the English title to Nova Scotia, was scarcely more than a truce between the two powers which had been struggling for ascendency during the beginning of the century. The French engaged in a long controversy with the English respecting the boundaries of Acadie, which had been defined by the treaties in somewhat general terms, and intrigues were carried on with the Indians, who were generally in sympathy with the French, for the annoyance of the English settlers. The Acadians were allied to the French by blood and by religion, but they claimed to have the rights of neutrals, and that these rights had been

granted to them by previous English ofi&cers of the crown. The one point of special dispute was the oath of allegiance demanded of the Acadians by the English. This they refused to take, except in a form modified to excuse them from bearing arms against the French. The demand was repeatedly made, and evaded with constant ingenuity and persistency. Most of the Acadians were probably simple* minded and peaceful people, who desired only to live imdisturbed upon their farms ; but there were some restless spirits, especially among the young men, who compromised the reputation of the community, and all were very much under the influence of their priests, some of whom made no secret of their bitter hostility to the English, and of their determination to use every means to be rid of them.

As the English interests grew and the critical relatiqns between the two countries approached open warfare, tho question of how to deal with the Acadian problem became the commanding one of the colony. There were some who coveted the rich farms of tli,e Acadians ; there were some who were inspired by religious hatred ; but the prevailing spirit was one of fear for themselves from the near presence of a community which, calling itself neutral, might at any time offer a convenient ground for hostile attack. Yet to require these people to withdraw to Canada or Louisburg would be to strengthen the hands of the French, and make these neutrals determined enemies. The colony finally resolved, without consulting the home government, to remove the Acadians to other parts of North America, distributing them through the colonies in such a way as to preclude any concert amongst the scattered families by which they should return to Acadia. To do this required quick and secret preparations. There were at the service of the Enghsh governor a number of New England troops, brought thither for the capture of the forts lying in the debatable land about the head of the Bay of Fundy. These were under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel John Winslow, of Massachu