George Washington Cable.

“Posson Jone.”

Notes to the next group

- Remove the cruft repace with figures

- Tables, picture descriptions, index, table of contents are left

A history of Louisiana

Magruder, Harriet

Class L^

Book /_,

Copyright N^

COPYRIGHT DEPOSn^

\

PREFACE

In writing this book my aim has been to give to Louisiana children the history of their State in a clear, simple, and interesting manner. Historic material has been collected from many sources, but only that has been used which comes within the comprehension of the child. An attempt has been made to foster State pride by dwelling on the sufferings and conflicts of the State, and of her final triumph through the courage, endurance, and love of freedom inherent in her citizens. An effort has also been made to put stress upon the importance of the struggle between the Latin and Anglo-Saxon races for our country, and the results leading to English domination and self-government.

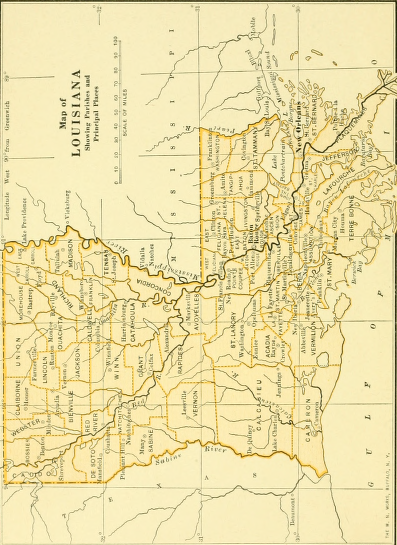

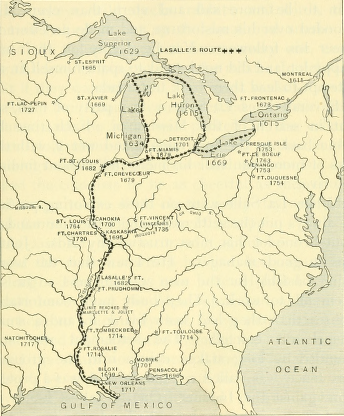

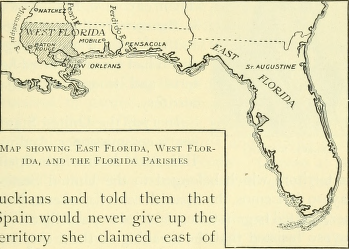

The teacher is urged to make frequent use of the maps. It is suggested that for the first lesson in Louisiana history a review be given on the maps of North America and the United States, the teacher showing the relation of Louisiana to the other parts of the country. Outline maps will also be found useful, as children will be interested in marking the discoveries and settlements as they progress.

Thanks are due many friends for their interest in the work during its preparation. I am especially indebted to Mr. Waddy Thompson, of Atlanta, Georgia, who wrote the introductory chapter, and who read and criticised the manuscript; to Dr. A, B. Coffey, of the Louisiana State University, who read portions of the manuscript; to Colonel T. D. Boyd, President of the State University, for his courtesy in placing maps at my disposal; and to Mr. T. H. Harris, Superintendent of Education, at whose instance, when teaching in his school several years ago, I was encouraged to write a history of Louisiana for children. My warmest thanks are due Dr. Walter L. Fleming, of the State University, for his untiring aid and helpful suggestions; while more than the usual indebtedness is due from me to my publishers.

HARRIET MAGRUDER. Baton Rouge, La., January, 1909.

Introductory

I. Hernando de Soto

II. Marquette, Joliet, and La Salle .

III. La Salle attempts to plant a Colony in Louisiana

IV. The End of La Salle's Colony

V. Iberville

VI. Iberville explores the Mississippi

VII. Iberville and Bienville

VIII. Bienville visits the Red River Country

IX. Bienville at the Head of the Government

X. Antoine Crozat

XI. St. Denis

XII. John Law

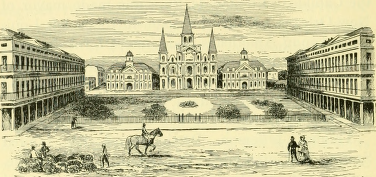

XIII. The Founding of New Orleans

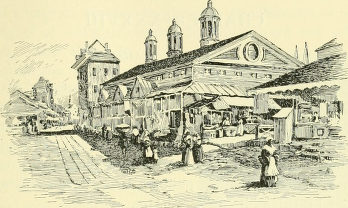

XIV. The Mississippi Bubble — New Orleans, the

tal

XV. The Ursuline Nuns — The Casket Girls

XVI. The Natchez Massacre ....

XVII. Defeat of the Natchez ....

XVIII. Bienville, the First Royal Governor .

XIX. Marquis de Vaudreuil ....

XX. The French and Indian War .

XXI. Louisiana ceded to Spain

XXII. The Acadians

XXIII. Don Antonio de Ulloa ....

XXIV. "The Revolution of 1768" .

V

Capi

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

XXV. Don Alexander O'Reilly .

XXV'I. Execution of the Revolutionists

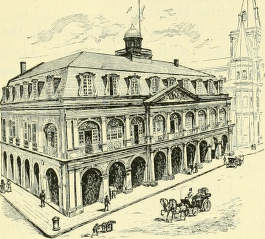

XXVII. The Cabildo ....

XXVIII. The American Revolution

XXIX. The Capture of Florida .

XXX. The Navigation of the Mississippi

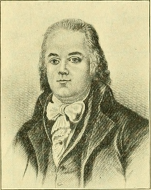

XXXI. Baron de Carondelet

XXXII. The New Treaty with Spain .

XXXIII. The Last Years of Spanish Rule

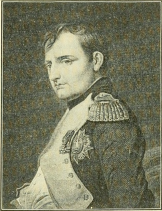

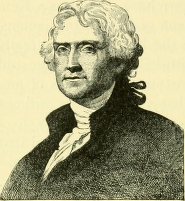

XXXIV. Louisiana ceded to the United States XXXV. The Formal Transfer of Louisiana

XXXVI. Territory of Orleans

XXXVII. The Land and the People in 1803

XXXVIII. William C. C. Claiborne .

XXXIX. The Floridas ....

XL. Aaron Burr

XLI. The Florida Parishes

XLII. Admission of Louisiana as a State

XLIII. The Baratarian Pirates .

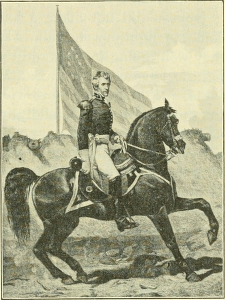

XLIV. General Andrew Jackson comes

Orleans

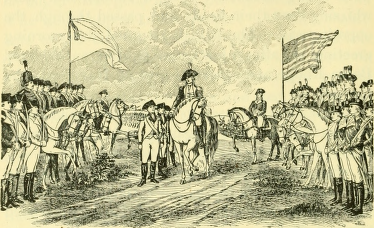

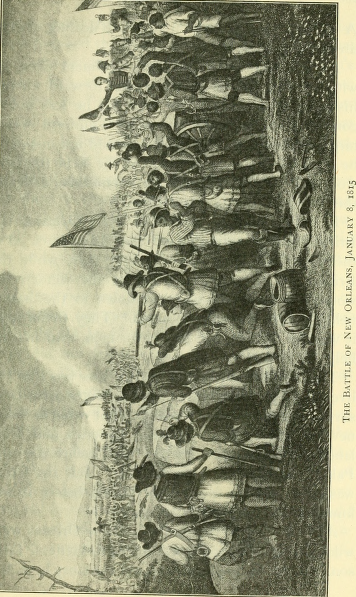

XLV. The Battle of New Orleans .

XLVI. The Middle Period .

XLVII. Zachary Taylor ....

XLVIII. Audubon

XLIX. The Causes of the Civil War .

L. The Early Years of the War .

LI. The War after the Capture of New Orleans

LI I. Louisiana in 1864

LIII. Life in Louisiana during the War

LIV. After the War ....

LV. The Ku Klux Klan .

TO

New

PAGE 148

i6o 166 172 179 187

193 198 205 212 218 224 229 234 239 244

249

256 262 271 277 285 291 298

304 310

315 321 326

CONTENTS

vu

PAGE CHAPTER

LVI. The Revolution of 1874 . , . • • 333 LVII. Development of the State . . • -337 LVIII. Louisiana Customs and Superstitions . • 344 LIX. Louisiana Customs and Superstitions {con

thmed} ....•••• 35° LX. Conclusion . . • 357

Appendix 3

Index ^5

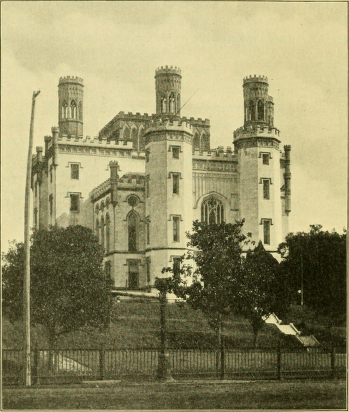

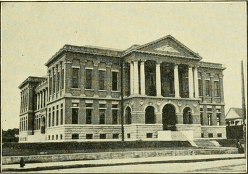

I'iiK Capitoi. at Baton Rou(;k

INTRODUCTORY

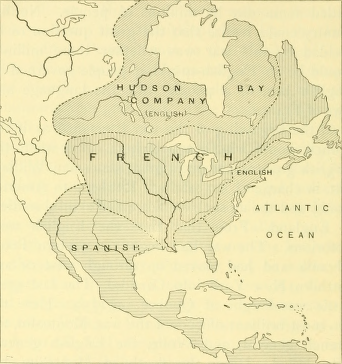

Consult Maps of North America and the United States.

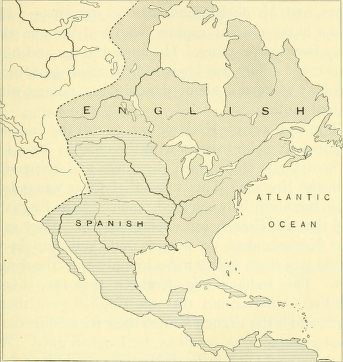

When Columbus discovered America (1492), he was serving the king and queen of Spain. For this reason Spain claimed all of America. It was not long before the Spaniards began to make settlements in the New World. They settled in the West Indies, in South America, Central America, and North America. Their settlements within the present limits of the United States were in what is now known as Florida, in the southeast, and what is now known as New Mexico, Arizona, and California, in the southwest.

Between these extreme points on the North American continent the Spaniards had not been able to make a settlement. The story of how the march of the Spaniards through Louisiana, under De Soto, ended in disaster is told in Chapter I.

The two nations of Europe that were in those days the rivals of Spain — the English and the French — did not acknowledge the claim of Spain to all of America; yet they were slow in making settlements in America to oppose the Spanish claim.

The first permanent English settlement in North America was made at Jamestown, in Virginia, in 1607, and in the following year the French founded Quebec, in Canada. From these settlements the English and French colonies grew steadily, though the English colonies grew the faster.

The English colonies spread up and down the Atlantic coast, from the French territory in Canada to the Spanish territory in Florida. On the other hand, the French settlements extended westward from the Atlantic coast of Canada to the region of the Great Lakes.

By this time Spain's power as a great nation had almost passed away. England and France had become the great nations of the world and, naturally, there was intense jealousy between them. Wars to decide which people should be master of the world became frequent between the English and the French. Each side realized that the nation that should finally control the North American continent would win in the struggle. The great region of North America known as the Mississippi Valley was then unoccupied by white people. Both the Enoflish and the French knew that whoever held the Mississippi Valley would control the continent.

The history of the present State of Louisiana begins in 1673, when Marquette and Joliet started from Canada to explore and claim for France the great valley drained by the Mississippi River. A full account of the journey of these brave explorers is given in Chapter IL

HISTORY OF LOUISIANA CHAPTER I

HERNANDO DE SOTO

All the boys and girls of Louisiana love their native State. When they learn of her early history, of her heroic struggles for liberty, and of her noble men and women, they will love her still more.

It is an interesting story. Louisiana has not always been as we know her: a rich and prosperous State, with large cities and towns and railroads and steamboats, and big plantations of rice, sugar cane, and cotton. About two hundred years ago the whole country was only a great forest, where panthers, bears, wild cats, and buffaloes roamed about, and the dreary swamps and bayous were the homes of alligators and snakes. The only people here then were Indians with their bows, arrows, and tomahawks; and the only houses were little huts, called wigwams, which were scattered through the forest.

It was in the year 1492 that Columbus bravely sailed from Spain across the unknown ocean and discovered the islands of the West Indies and later the mainland of Central and South America.

His followers made small settlements on Cuba and other islands. These Spaniards heard from the Indians wonderful stories of a beautiful land that lay not far distant across the blue waters, meaning what is now the southern part of the United States. They gave glowing accounts of the gold and silver and precious jewels that could be found in this country.

The Spaniards set out eagerly to find these riches. They visited Florida, the nearest point to Cuba, and it is thought that some coasted along the shore as far west as what is now Louisiana and sailed a short distance up the Mississippi River. They found no riches. Many died of hunger and cold, or were killed by the Indians. Those who did not die wandered forlornly through the country, and at last reached home half starved and nearly naked. Yet these men, who had found no gold or silver, and had seen only swamps and forests and Indians, told of the gold that was to be found in Florida. They said it was the richest land in the world.

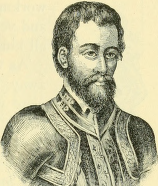

Hernando de Soto, a young Spanish nobleman living in Cuba, heard these stories and believed them. He had helped to conquer Peru in South America, and his share of the gold taken from the Indians there had amounted to a great fortune. He wanted still more riches, and he was ambitious to become a great conqueror and to govern the countries he should overcome.

Hernando De Soto

De Soto soon went to Spain to get permission from the king to conquer Florida. He laid his plans before the king and offered to bear all the expense. The king gave consent and appointed him governor for life over all the country he might conquer, and granted him an immense estate in his own right.

When it became known that De Soto, noted for his bravery and his wealth, and as one of the conquerors of Peru, was to undertake the conquest of Florida, he was the man in all Spain most to be envied. Young nobles from all over Spain and Portugal came to his casde and asked to go with him, offering to bear part of the expense. Some even went so far as to sell their homes to get the money. So De Soto was troubled, not to get enough men for the expedition, but to choose from the many who wished to go. He selected about a thousand, and among them vvere soldiers who had fought in many hard battles, and the pick and flower of Spanish cavaliers.

The expedition was fourteen months getting ready. Everything was put upon the ships which rich, luxury-loving people thought needful. There were beautiful clothes of velvet and satin, embroidered in gold and silver and pearls, chairs of exquisite workmanship, soft beds, and silken and velvet quilts, costly dishes, and all kinds of good things to eat.

As the fleet of ten vessels sailed away from Spain, flags on shore were waved, bands played, and the people shouted, wishing Godspeed to the most brilliant expedition that had ever left any shore. When the Spanish vessels neared Florida in the year 1539, they saw along the coast alarm fires which the Indians had built. But when they entered what is now Tampa Bay, lot an Indian was in sight. The Indians were there, though, gliding from tree to tree with a stealthy tread and peeping out with angry eyes. They watched the proud Spaniards as they came from the ships armed with swords and crossbows and clad in armor of glittering steel, leading their war horses covered with shining metal, no less proud than their masters, as they arched their necks and tossed their beautiful heads.

Though the Indians did not know these men, others of the same race had been in their country and had treated them so cruelly that they resolved

Spanish Knight of 16TH Century

that these strangers of such fearful beauty must be fought to the death.

f

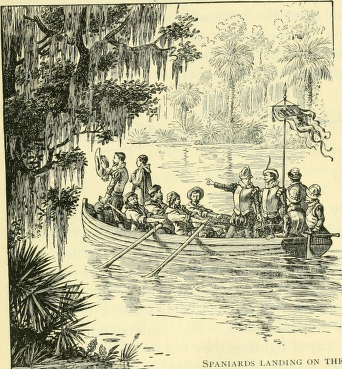

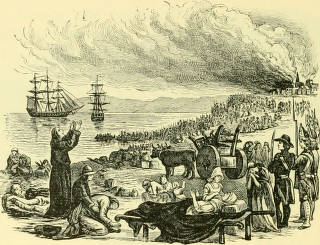

Spaniards landing on the Gulf Coast

The scenery is from nature.

The Spaniards, all unconscious of a hidden foe, raised the Spanish flag, and took possession of the country in the name of their king. It was in May that they landed, and it seemed as if all the flowers of all the earth were crowded together into this one spot, and had burst into bloom to welcome them. Tired after the long sea voyage, they threw themselves on the tender green, and drinking in long draughts of the perfumed air, laughed and sang and shouted in the very joy of life and youth and hope.

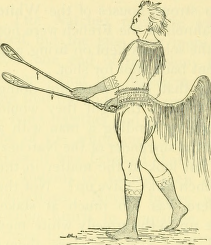

Indian Bow and Arrows

They talked late into the night, and their talk was of gold; and as they slept under the southern stars they dreamed of gold and glistening jewels.

The next morning, just when the stars were growing pale, they were awakened by the blood-curdling war cry of the Indians, who made a fierce attack upon the Spaniards. Not understanding the Indian way of fighting, they ran to their boats. Many of the Spaniards were killed. When the Indians went away, De Soto again took his men on shore, and after marching about six miles, camped near an Indian village. The Indians were afraid to attack them openly, but every Spaniard straying from the post was instantly killed. De Soto sent presents to the chief, and tried to gain his friendship, but he was not to be won over. Ten years before, Spaniards had taken his mother and before his eyes had caused her to be torn limb from limb by bloodhounds. He now sent back the presents with the scornful reply: "I want none of their presents; bring me their heads."

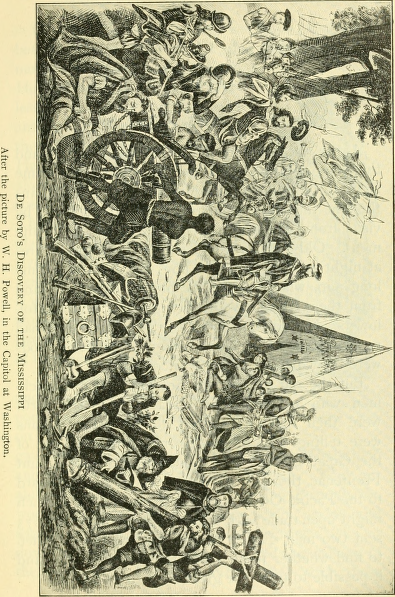

This was the beginning of De Soto's troubles, and it foretells the whole story. The Spaniards spent three years going through the present States of Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi. They found no rich cities, nor gold, nor silver. They found only miserable huts and half-clad savages as they cut their way through the pathless forests. Step by step the right of way was contested, and the tale is only one of cruelty and bloodshed as the Indians and the Spaniards struggled for mastery.

At last, worn out, sick, and hopeless, the few of the brilliant company who were left, stood on the bank of the Mississippi River. As De Soto gazed upon the waters of the great river, his thoughts must have wandered back to that morning when his fleet pushed out from the shores of Spain; to the fortunes wasted; to the hopes wrecked; to the nameless graves stretching from Florida to the Mississippi. He would have a name in history, but was it worth the price ?

Still determined to find gold, he crossed the river and marched on through what is now Louisiana and Arkansas; yet he found no gold. Disappointed at his failure, he returned to the Mississippi. Here he brooded so much over his tragic fate that he soon fell sick with a fever. The once darins: leader lay without a shelter over his head, surrounded by a few half-starved though loyal men. He asked his men to forgive him for all the trouble he had caused them, and named a leader to whom he told them to be true, as he would lead them home.

Finally the soul of the great explorer went out. In the darkness of the night three or four sternlooking men rowed into the middle of the river and gave the body of their chief into its keeping. All was over now, and their only thought was to get home. After many trials they reached the Spanish settlement in Mexico.

Questions. — I. Who lived in Louisiana before the white men came ?

2. Describe the country as it was then.

3. Who were the first Europeans to visit Louisiana ?

4. Tell the story of their expedition.

5. What was their object in exploring this country?

6. Describe De Soto's discovery of the Mississippi and the last months of his life.

CHAPTER II

MARQUETTE, JOLIET, AND LA SALLE

After the death of De Soto one hundred and thirty-one years passed before white men came again to the valley of the Mississippi. The Indians thought that they would be troubled no more by visits from the palefaces (as they called the white men). Old squaws would sit by the wigwam fires at night and tell the little boys and girls of a time long ago, when palefaces came to take their land from them, and how the strange chief and his followers went floating down the great river and had never been heard of since; and now the deep woods were their own for all time to come.

But the old squaws did not know that Frenchmen who had settled in Canada far to the north were then listening eagerly to the tales Indians were telling of a mighty river that flowed west of the Great Lakes. The Canadian governor, Count Frontenac, thought that this river flowed westward to the Pacific Ocean, and that through it the French might open trade with India. He therefore in 1673 sent two men. Father Marquette and Louis Joliet, to find whether these Indian stories were true, and if possible to trace the great river to its mouth.

Governor Frontenac could not have chosen two better men for the work. Father Marquette, as his name tells you, was a priest. He was noble-hearted and fearless. He had spent many years among the Indians, teaching them the Christian religion. He had learned how to get along with them and could speak six Indian languages. The Indians would therefore be glad to help him find the great river. Joliet was a shrewd business man, and the governor left it with him to decide whether it would pay to establish trade between Canada and the Indians of that part of the country.

The explorers took two canoes and some smoked meat and corn, and with five men started on their voyage. The Indians gave them directions how to get to the Mississippi, and made a kind of map to guide them. They got along very well, sometimes tramping through the woods carrying the canoes on their backs, and sometimes paddling their canoes across a lake or down a river. Finally they reached the village of the Wild-Rice Indians. When they told these Indians where they were going, they were advised to turn back, for there, tlie Indians said, sure death awaited them. These Indians told them that on the banks of the Mississippi there were ferocious tribes that killed every stranger who came among them, without giving him a chance to say why he came.

Father Marquette

From the statue by G. Trentenove, in the Capitol at Washington.

The Indians also said that in a certain part of the river was a terrible demon who roared so loudly that the ground trembled, and when travelers got near him, he sent up a whirl of water which drew them into the abyss below; that in other parts of the river were most hideous monsters who opened their wide jaws and took in canoes and men and chewed them up as if they were only a little taste.

People were very superstitious in those days and believed all sorts of foolish stories, and it is not unlikely that Joliet and Father Marquette believed these; but they went on. The good priest knew that many of his brother missionaries had been burned at the stake and horribly tortured in other ways, and that one of them had been roasted alive and eaten in the presence of his comrades. Yet he believed that, if souls were to be saved, no man should shrink from his duty.

Louis Joliet

After the bronze relief tablet by E. Kemys in the Marquette Building, Chicago.

So on they went, and in one of the Indian villages on a beautiful prairie stretching toward a grove of oaks they saw a cross erected, which the Indians called the Great Manitou of the French. It was the custom of the Indians to select some object and worship it as their god, calling it Manitou. Naturally, when they saw some Frenchmen who had previously been in the neighborhood erecting a cross, they thought the cross was the Frenchmen's Manitou. The Indians had decorated the cross with deerskins, red girdles, bows, and arrows. You may be sure that the Frenchmen were glad to see this sign that the Indians were friendly. The old chief of the tribe gave Father Marquette a pipe decorated with bricrht feathers. The giving of the pipe was to show that there was to be peace and friendship between the Indians and the white men, and not war. Such a pipe is called the calumet. The chief told the good father that if he came to any warlike tribes just to show the calumet, and he would not be harmed. A guide was also given them to the Wisconsin River. "^ After paddling down this river for ten days, the explorers saw a rapid stream dashing toward the south. It was the Mississippi River. Joyfully they guided their light canoes into this great body of water. They went as far south as the Arkansas River, and then, hearing that the Indians were very unfriendly below, decided to return. They had found out that the soil was rich, that many Indians lived on the banks of the newly discovered river, and that the river did not flow westward into the Pacific, but southward into the Gulf of Mexico.

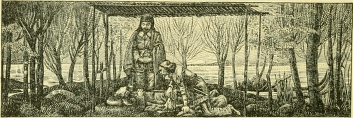

The Death of Maroueite

After the bronze relief tablet designed by H. A. McNeill, in the Marquette Building, Chicago.

The return trip upstream was very slow. Marquette, worn out by the hardships of the journey, died before the party reached Canada. When Joliet arrived in Canada and told the news of the discovery, the people were wild with delight, and in the city of Quebec they went in a procession to the cathedral, where they sang the Tc Dcuiu. The excitement did not last long. Joliet went back to his business affairs; the furor of the discovery died out; and the Mississippi seemed again forgotten.

There was one man in Canada who had not forgotten. This man was Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle. He was born in France and had spent several years in that country in a convent of the Jesuits.

From time to time there came to him in the quiet convent stories of the new world across the sea, and

La Salle became greatly interested in all he heard concerning Canada. He listened excitedly to how cities were being built, how immense tracts of land could be had for almost nothing, how fortunes could be quickly made by trading with the Indians for furs; and he felt that this new world, and not the convent, was the place for him. He therefore crossed the ocean to Canada and obtained a large tract of land near the city of Montreal, where he built houses for settlers and carried on a flourishing: trade in furs. He spent two years in exploration. What he learned of the Mississippi awakened ambitious dreams; he was no longer content with wealth, but wanted to gain power and fame by making great discoveries.

La Salle went to Governor Frontenac and laid his plans before him. He explained that while the Mississippi emptied into the Gulf, yet the rivers flowing into it from the west doubtless led to India; and that the exploration of these rivers might lead to an immense trade between the East and the French in America. Moreover, he saw that a chain of forts and trading posts encircling the Great Lakes and built all the way down the Mississippi to its mouth would secure the Mississippi Valley for France and would bring to its king and all who would join the enterprise such wealth as the world had never dreamed of.

The governor became as enthusiastic as La Salle; but this grand project would take a great deal of money, and as he had no right to give the government's money for such a purpose, he advised La Salle to go to France and submit his plans to the king. Governor Frontenac gave him letters of recommendation to influential men in Paris, who could bring him in touch with King Louis, among whom was Conti, a prince of the royal blood.

It was through Prince de Conti that La Salle was able to lay what was called a memorial before Colbert, the king's minister. In this memorial he told in glowing language of the beauty of the Mississippi Valley and the richness of the soil. He said, too, that aside from the fur trade, factories could be established, as the wild cattle had fine wool which would make good cloth and hats; that cotton also grew there, and fish, game, and venison were so plentiful that a colony could be supported at little expense. He told the king that if France did not act quickly, England would seize the country. Then he stated that the difficulties of the undertaking were due to the immense territory to be traveled, the cost of men, provisions, and ammunition, the danger from the Indians; then, most important of all, that he had no money.

In reply to his memorial, the king graciously gave him permission to continue his discoveries, but would give him no financial aid. La Salle had then to get the money as best he could.

Questions. — I. What nation sent the next explorers to the Mississippi Valley?

2. What was their purpose?

3. Tell about the two men who explored the upper Mississippi.

4. Describe their equipment for the journey.

5. Compare these Frenchmen's experiences with the Indians and the Spaniards' experiences.

6. How did La Salle plan to open the trade between Canada and India?

CHAPTER III

LA SALLE ATTEMPTS TO PLANT A COLONY IN LOUISIANA

When La Salle got back to Canada, the first thinghe did was to raise all the money he could; and as his relatives and friends believed in him, they let him have all they could spare. He spent some time in building large vessels and stocking them with everything that would be needed. In 1679 the expedition started westward by way of the Great Lakes. La Salle built a fort wherever the Indians would let him.

As he moved on his journey. La Salle collected a large supply of valuable furs. Before leaving the Great Lakes he sent the furs back to Canada on one of his vessels named the Griffin. The furs were to be exchanged for bright-colored blankets, clothes, beads, knives, axes, guns, ammunition, and other things that Indians like. By trading these things with the Indians he hoped to keep them friendly. He then went on to explore the Illinois River.

Two years had passed, and up to this time all had gone well, but now misfortunes came thick and fast. Provisions had almost given out, and there were no goods left to trade with the Indians. La Salle waited anxiously day after day for news of the Griffin. The vessel never returned, and word came that she had been wrecked and all her cargo lost. About this time, also, came the news that his property in Canada had been seized for debt.

But the greatest trouble La Salle had to meet was with his men. They had traveled many hundred miles, endured great hardships, and had made no money. They became discontented, had almost mutinied several times, and both feared and hated their leader. La Salle, though a man of remarkable energy and perseverance, did not know how to attach men to hini. He could command, but did not know how and when to give way; and this is a good thing for even a leader to know.

At last the men began to look upon La Salle as only an idle dreamer who was leading them a wildgoose chase; and on Christmas, the day when angels sang peace and good will to men, they tried to kill him by putting poison in his soup. No one could read La Salle's thouo^hts in his face,' and he did not talk of his disappointment. The only ex\ pression he gave of his feelings was in a very pathetic way. He built a new fort and named it Creve Coeur — Broken Heart.

RoBERr UK La Salle

By this time conditions became desperate. The men were nearly starved. Though it was midwinter, La Salle determined to walk back to Canada and get assistance for his party. He left the fort to Tonti, the only man in all the party who was still his friend. Tonti had come with him from France.

Some months later La Salle returned to the fort. He found it indeed the fort of the Broken Heart. While he was away, the terrible Iroquois had made a raid through the country. They had attacked the fort and left it a blackened ruin. Not a human being was there to greet him. La Salle thought that Tonti and his men had been killed. They, however, had been taken prisoners by the Iroquois. Through the intelligence and courage of Tonti, who had been an Italian officer, they finally escaped and joined La Salle.

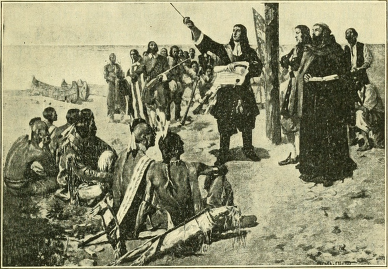

As they were now close to the Mississippi River, La Salle decided to push on rapidly to the great river. In February, 1682, they entered the Mississippi. They journeyed slowly downstream, visiting the Indian tribes on either side, and at the end of two months reached the mouth of the river. Eagerly the hardy band jumped on shore. After singing the Te Deum they nailed to a tree a cross bearing the arms of France, and La Salle took possession of the country in the name of King Louis XIV of France, and called it Louisiana in honor of the king.

For thirteen years La Salle had labored to reach the mouth of the Mississippi. At last he had done

La Salle at the Mouih of the Mississippi

SO. But there was more work yet to be done. In order that France m.ight hold the country bordering on the Mississippi, French colonies had to be planted in it. La Salle went back to Canada, and in a short while sailed for France. He wished to lay the newfound treasure of Louisiana at the feet of his king.

La Salle was received with honor at the court on account of his great achievement. The king listened to him favorably and gave him more help than he had expected toward establishing a colony in Louisiana. Four vessels were fitted out with what was necessary to start a new colony. There were drugs for the little drug store of the village to be built on the banks of the Mississippi, and articles for the dry goods store and for the grocery store. Then there was a priest to preach to the colonists. The stores that were planned for the new colony were not like ours, for everything was to be given to the settlers until they could make enough money in the new colony to buy what they wanted.

About a hundred soldiers went along to protect the colonists, and in the party were merchants, carpenters, laborers, several families with children, and young women w^ho went out to be married.

The future seemed very bright for La Salle and his colony, but sometimes a man fails when he has everything to help him, and the cause is in himself alone. La Salle knew notliing of the sea, yet he asked to be made sole commander of the expedition and that the sailors and pilots should sail just as he ordered them. But the king's minister would not allow this, though he did what ought to have satisfied a reasonable man. He put Beaujeu, a captain of the royal navy, in command while at sea, and La Salle was allowed to direct the course of the ships and have entire control of the soldiers and colonists when they should land.

Neither La Salle nor Beaujeu was satisfied with this arrangement, for they were very jealous of each other. By the time they were ready to sail, Beaujeu had all the sailors and half the colonists hating La Salle. La Salle might even then have made friends with the crew and the captain, for Beaujeu was not a bad-tempered man; but La Salle was cold and suspicious, and was too proud to care much what any one thouo-ht of him.

Questions. — i. What explorer first reached the mouth of the Mississippi?

2. Tell about the naming of Louisiana and the ceremony of taking possession of the country.

3. In what year did these events occur?

4. Tell what you know about the early trading with the Indians.

La Salle's Autograph

CHAPTER IV

THE END OF LA SALLE's COLONY

The fleet set sail from France in 1684. It was not a happy voyage, as the two leaders were so unfriendly. They safely reached the Gulf of Mexico, but as neither of tliem knew the coast, they passed the Mississippi without knowing it. On New Year's Day (1685) they landed on a low, sandy shore at a point in Texas which La Salle took to be the mouth of the Mississippi. He soon began to be uneasy, however, for fear he had made a mistake. He asked Beaujeu to turn back and coast along the shore in search of the Mississippi. Beaujeu refused to do so. He said he had advised against landing where they had landed, as the water was too shallow for the ships, but now the thing was done; and as the weather was stormy and the coast dangerous, he was going back to France. Beaujeu, leaving two vessels with the colonists, sailed away.

La Salle soon found that his colony would have been a failure no matter where it had been placed, for none of the soldiers were trained, some of them having been worthless beggars around the church doors in Paris. None of the mechanics knew their trade; all were discontented and blamed him for their troubles. As a final blow, the two vessels left him by Beaujeu were wrecked. The colony was now stranded indeed, for as long as the vessels remained there was a hope of getting away.

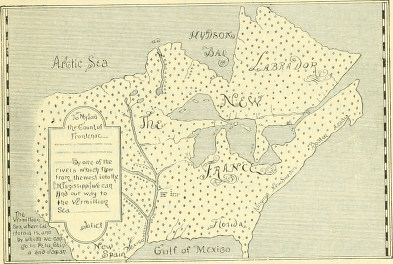

Map of the Country explored by La Salle

La Salle now saw that he had failed in what he had hoped to make the grand work of his life. He did not complain, but his disappointment caused him to be more sad and stern than ever. He brooded over his misfortune, and made no effort to cheer his followers. Yet he deeply felt their unhappy lot, and did not intend to spare himself in an attempt to lead them back to Canada.

Several times La Salle, with a party of men, set out in search of the Mississippi. Each time he came back to the fort ragged and weary, with the loss of more than half his men, and without finding the river.

When La Salle went on these exploring parties, he always put the settlement under the command of Joutel, one of his most trustworthy aids. Joutel was a good manager. He knew that the worst thing possible for the men was idleness, so he set them all to work. They built more comfortable houses than they had been living in, and a small chapel was erected. The settlement was surrounded by long stakes driven into the ground; this fence was called a palisade, and was a protection asfainst the Indians. On the tallest house in the fort were mounted eight pieces of cannon, two pieces at each corner of the building.

Sometimes Joutel gave the people a holiday, when all would 2:0 huntino;. The women and children always went too, because they could not be left behind for fear of an attack from the Indians. There was plenty of game on the wide Texas prairies. When the men had killed buffaloes, deer, wild turkeys, wild ducks, rabbits, and birds, the women helped to cut up the meat and smoke it. Then the colonists started home, every one, even the children, helping to carry the meat. Joutel said that if they wanted to eat, they must work.

After the colonists were settled in their new houses and the meat was packed in the cellars, Joutel told them that they might all gather in the evenings and sing and dance and play cards. He asked the colonists to be as cheerful as they could, and to go to the little chapel every day and pray that La Salle might find the Mississippi.

At last La Salle returned; again he had not found the river for which he had been searchino^ so long. The colonists now believed that La Salle would never find the Mississippi, and abandoned the hope to which they had clung that their king would send a ship to take them home. They could stand the strain no longer. Attacked by a disease caused by exposure and poor food, they did not have the strength to withstand it, and a large number died. La Salle nursed the sick as gently as a woman; and as soon as he could be spared, made the desperate resolve to seek help for his colony by going on foot from his settlement on the coast of Texas to Canada, a thousand miles away.

Of the forty men left he chose twenty and set out for Canada. Most of the men who accompanied La Salle on this trip hated him, and were ready at the least excuse to revolt. One day during his absence from camp, his nephew got into difficulty with one of the men and was killed. La Salle was not the man to let this pass unpunished. This the men knew well; so when he returned, one of the men hiding in the long grass shot him in the back. " There thou liest, great Bashaw," cried he. Then the men dragged his body into the long grass and left it.

La Salle's brother and two others of the party, one of whom was Joutel, got back to France. They tried to get the king to help the colony, but he refused. It is supposed that either the Lidians or the Spaniards killed all the remaining colonists. < You will remember that De Soto showed the way to the Mississippi Valley. La Salle traveled the whole length of the valley and added it to the French crown. Now let us see who will be the brave man to finish the work.

Questions. — Tell the history of the first settlement, in 1685;

|

I. |

The plans. |

|

2. |

The colonists. |

|

3 |

The leaders. |

|

4 |

The landing. |

|

5 |

Life in the Texas settlement, |

|

6. |

The fate of the colony. |

CHAPTER V

IBERVILLE

Shortly after the death of La Salle war broke out between France and England, and the French king had no time to think about Louisiana nor money to spend on her, for wars are very costly. During this time King Louis found that both England and Spain would be very glad to slip in and take Louisiana. Of course, this made him think his namesake was worth something; and when the treaty of peace was signed, Louis saw to it that England did not get any land in America south of Canada.

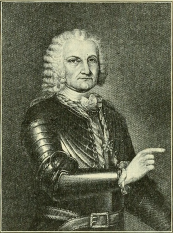

The French ministers of marine, Count Pontchartrain and his son, Count de Maurepas, were very patriotic men. They loved France and thought it would add to her wealth and importance to have flourishing colonies in America. When they learned that King Louis was thinking the same thing, both fatlier and son entered with energy into a scheme to send an expedition to Louisiana. It was to be managed differently from the last one. The ministers themselves would choose the man who should lead the mportant enterprise. They chose Pierre Lemoyne criberville, a voung Canadian officer. He and his ei"ht brothers were known to have fought bravely against the English, and Iberville had distinguished himself most of all. He was handsome, popular, and liked by both officers and men. Pontchartrain and Maurepas thought he was just the man for the work, and we think so too.

Count Pontchartrain

Two well-stocked frigates were given to Iberville. Before he sailed, he examined the provisions, the presents for the Indians, and the ammunition, and tried the guns to satisfy himself that everything was all right. The expedition left France in 1698. The Atlantic Ocean was crossed without any mishap. Iberville stopped on the coast of Florida. He liked the looks of the country so much that he thought he would take it also for France; but in a bay ahead he saw ships with tall masts. They belonged to a Spanish fleet. A Spanish officer came out in a boat and received him politely, but just as politely hinted that he had better pass on, as that part of the country belonged to Spain.

Pierre Lemoyne D'Ihervii.i.e

Iberville then sailed away in search of the Mississippi. He coasted around several beautiful little islands and entered Mobile Bay, but he was not interested in that harbor just then. Other islands were passed, and Iberville's brother Bienville, a boy of eighteen years, was sent ahead to find a good landing. He found a pass between two islands to the north, and one morning just as the dawn was breaking, Iberville in the ship Badinc, leading the way, landed at Ship Island. This island is off the coast of what is now the State of Mississippi, The men were tired after their long sea trip, and had a good time roaming about the island.

A little island that was near they named Cat Island, because they saw running about ever so many little animals which they took for cats." This is the kingdom of cats," exclaimed one of the men; but he was mistaken. They were raccoons. As soon as the sun came up, Iberville got out his spyglass, and across the water to the north about twenty miles distant he could see land. Indians were walking about the shore and some were paddling around in their canoes.

As soon as a few huts were built to protect the men from the weather, Iberville took Bienville and a few others and crossed over to the mainland. He carried with him some of his finest presents, for he was anxious to make friends with the Indians. As there were so many of them and so few French, he feared that if he did not make friends of them, they might kill all the French. Then, too, he wanted them to show him the way to the Mississippi. He need not have been afraid of the Indians, for they were equally afraid of him, and they all ran away just as the raccoons had done — all except one poor, old, sick Indian and a squaw, perhaps his wife, who peeped from behind a tree.

The next day the squaw brought several warriors of her tribe to see the French. Iberville asked them to go with him and look over his ship, but they were afraid to trust him. To show them he was honest, he said he would leave his brother with the tribe while the warriors were visiting the ship. Then the Indians went with him. Iberville gave them a good dinner, and the sailors showed them everything on the ship. There was not one on board who could speak the language of these Indians, but the French managed to understand that the savages knew nothing of the long-sought river.

The next day several Indians from another tribe came, and the French were able to make out enough to understand that they lived on the banks of a great river to the west. These Indians said that they were out hunting, and promised that on their way back they would stop and get Iberville and take him to the river„ But they did not keep their word, and that was the last seen of them. Then Iberville did what we must all do if we wish to succeed: he depended upon himself. The next day he set forth with two barges, about fifty Canadians, and enough provisions and ammunition to last a month. The mists and fog were so thick that they were soon in the gloomiest place they ever saw in their lives. They little knew that they were in the delta of the Mississippi. All day they moved slowly about the multitude of dreary-looking little islands, covered with long, quivering reeds growing up out of the water.

Their barges were too frail to battle with the tossing waves of the Gulf during the night; so they stopped on one of the islands which, even though overflowed, seemed more hospitable than the stormy sea. The men cut down reeds and piled them up so as not to have to lie or sit in water.

The next afternoon a fearful storm almost swept them from the island. If you had been there, you would have thought that if you were only spared, you would never wish to go out with an exploring party again. Perhaps some of these men thought so too, but they had started upon the work and had to go through with it; then, too, they were under the command of a man who did not stop till he had finished what he had undertaken. When the storm had subsided sufficiently for tliem to start out again on their journey, a strong wind blew them toward the mainland. Iberville kept as near the shore as possible for fear of making La Salle's mistake of passing the mouth of the river.

One afternoon, just about dusk, a furious wind was driving the barges against what seemed to be a rocky cape rising above the surging water. Some decision would have to be made quickly, for night was almost upon them. To remain in the open Gulf was certain death; to steer toward the rocks seemed almost as certain death. Iberville decided to make a desperate attempt to round the cape. He took hold of the tiller, and his barge plunged forward, followed closely by the other. To his amazement, the cape broke into crags with fresh, muddy water gushing out between them. The crags were not rocks at all. Iberville examined them and found they were only driftwood that had been coming down the river for hundreds of years, and had been stuck together with mud which the sun had hardened into a kind of cement. Iberville hoped that he had found the mouth of the Mississippi River.

Questions. — I. Tell what you can about the leader of the second expedition of colonists.

2. Where did they land and build their first houses?

3. Describe Iberville's hunt for the mouth of the Mississippi.

4. Where were the Spaniards settled in North America at this time?

CHAPTER VI

IBERVILLE EXPLORES THE MISSISSIPPI

The only thing for Iberville to do now was to keep on until he found out exactly where he was. After the boats had gone about a hundred and twenty miles up the river, they came upon some Indians who ran as the French came near; but one of them was a brave young fellow, and he stopped and faced the newcomers. They made friendly signs and persuaded him to get into their boat. He was a Bayougoula, and led them to the country of the Bayougoulas and Mongoulachas, who received the explorers kindly and gave them a supper of stewed chicken. The hungry men enjoyed this homelike dish and felt that they had found a pleasant country where chickens grew wild; but the Indians said they were only a few that had been taken from a wrecked vessel.

From what the Indians told Iberville he was more convinced than ever that he had found the river he was seeking, but he was not the kind of man to rest while there was the least doubt. He thought it best to go on up the river about five days' journey to the Houmas Indians.

35

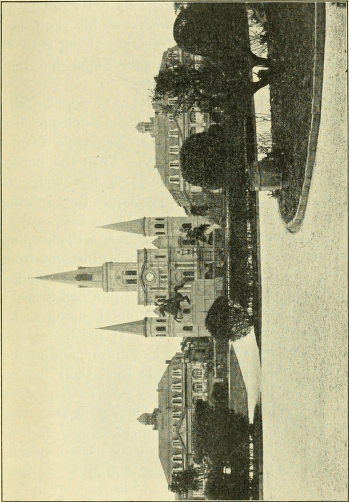

As the explorers passed up the river, they came to a part of the country which was higher than any they had seen. On the bank they noticed a long red pole, with heads of fish and pieces of bearmeat stuck on it, which some of the Indian hunters had offered to the spirits for giving them good luck. One of the Frenchmen said it was a " baton rouge " (red stick), and Baton Rouge it has been ever since, for the capital of your State is now where the long red stick once stood.

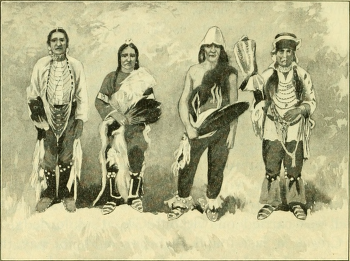

When they reached the Houmas, the chief came out to meet them, and Iberville gave him some of his most beautiful presents. The chief then entertained the French in the very best Indian style. A big dinner was given, and when they could eat no more, they smoked a long while. Iberville did not like to smoke, as it made him sick; but the Indians would have thought him very rude had he refused, so he puffed away, for he wanted to keep them in a good humor. After the dinner and smoking were over, some boys and girls in bright paint and brilliant feathers, with jingling pieces of metal on arms and wrists, bounded into an open space, dancing a wild, fantastic dance, moving their graceful feet and slender bodies in time with the music of pebbles rattled in hollow gourds. The musicians rattled softly at the slow parts, and more and more furiously as the dancers whirled round and round, and in and out. When the dancers retired, out came the young braves, throwing and catching their tomahawks and knives, and singing the terrible war song. This ended the entertainment.

When the young people were gone, the chief of the tribe and Iberville sat down for a long powwow, as the Indians called their conferences. The chief assured Iberville that he was sailing on the river he was looking for, and had once passed through the village, on his way to the Iberville's Autograhimouth of this same river in search of La Salle. Then one of the guides spoke up and told Iberville that the Mongoulacha chief had a letter which Tonti had left with him to be given to a man who would come up from the sea, meaning La Salle.

Iberville now felt that it was useless to 2:0 farther. He therefore told Bienville to go down the river to the Gulf, and cautioned him not to forget Tonti's letter. In the meantime Iberville took a few men and explored another part of the country He came to a small bayou which led to the Gulf through two broad lakes. He named these lakes Pontchartrain and Maurepas for the two ministers through whose influence he had been sent to Louisiana.

The two brothers reached Ship Island within a few days of each other. Bienville brought with hini the letter which Tonti had written to La Salle. Tonti wrote in the letter that, as he had heard that La Salle had left France with a party of emigrants for the Mississippi, he had gone to join him with twenty Canadians and thirty Indians. The faithful Tonti closed his letter by saying: "It is the greatest disappointment for me to have to return without having the fortune to find you. Though we have not found any trace of you, I do not despair that God will grant a full success to your enterprise. I hope this with all my heart, for you have not a more faithful follower than I, who sacrifice everything to follow you." The faithful friend of La Salle did not know that his leader had been murdered in Texas and his body thrown into the bushes.

Iberville was now sure that he had found the Mississippi. The next thing to do was to plant a settlement. It was necessary to build a fort as quickly as possible, as the supply of provisions was Quettins: low and he had to hasten back to France for more. He had wanted to build the fort on the Mississippi River, but he could not get his large ships through the passes of the delta. After looking at several places, he chose a piece of high ground on the shore of the Bay of Biloxi.

None of the men were skilled workmen, but they were so tired of roaming around and of being on shipboard that they were glad to get to work. Some cut down trees and built the fort, while others, taking the barges and httle boats, carried thino^s from the vessels to the fort. You children would have had a fine time if you had been there. After everything was clean and in good order Iberville went back to France. Before leaving he put Sauvole, one of his faithful ofificers, in command, and Bienville next in command.

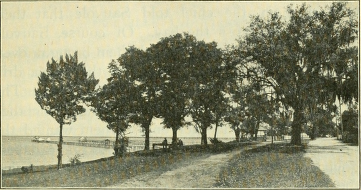

Copyrighl, iqoj, by Detroit Photographic Company.

The Coast at Biloxi

The settlers had not been in their new fort long before company came. The Bayougoula chief with some of his warriors came to return the visit of the French. It was now the Frenchmen's turn to entertain. It cost them something too, for the Indians expected to receive presents. After bright-colored shirts and other presents had been given, the Indians were taken over the fort. There are many things we never notice because we have been used to them all

our lives; but if you can imagine yourself a savage who has never been among civilized people, you can understand how many new and curious articles the Bayougoulas found to wonder at.

When the Indians saw there was so much to interest them, the chief told Sauvole that their squaws were across the bay. Of course, Sauvole gallantly took the hint and had them brought over. For their pleasure he put the men through a drill and marched them to the beating of the drum. The Indians thought this the most thrilling music they had ever heard, and each one of them wanted the drum; but Sauvole could not spare it. The Bayougoulas went away delighted, the chief promising the French the friendship of his tribe.

Questions, — I. Tell about the Frenchmen's first visit to the site of Baton Rouge.

2. Describe some of the Indian customs of amusement and their entertainment of guests.

3. Tell what you have read about the man for whom Lake Pontchartrain was named.

4. What place did Iberville select for building the first fort and settlement? Find it on the map in the front of this book.

CHAPTER VII

IBERVILLE AND BIENVILLE

Bienville had been Iberville's right-hand man in making friends with the Indians. He had Hved among them in Canada and had easily learned many of their languages. Moreover, he had a friendly, tactful way. He was fair in his dealings with the Indians, and they liked him. Before Iberville left for France, he had a talk with his brother and told him what he wished him to do while he was away. He said that he had heard that the English were thinking of sending a company of settlers to the Mississippi, and that Bienville must strengthen the French hold by exploring more of the country and making friends with as many Indian tribes as possible.

Bienville went first among the Indians on the northern shore of Lake Pontchartrain, and while there he was told that two days before they had been attacked by another tribe headed by two Englishmen. Several days later he was paddling down the Mississippi when, on turning a bend, he suddenly came upon an English vessel. Bienville rowed up to it and went on board. He found that he had known the commander, Captain Barr, in Canada; and in the course of their conversation the captain told him his government was about to send out several shiploads of people, and that he was examining the banks of the river to find a good place to settle, though he was not quite certain that he was on the Mississippi. Bienville told him that all this country belonged to the French, who had a strong fort and soldiers not far away. The English captain then turned and sailed away. Ever since that time the bend in the river has been called the English Turn.

When Iberville got back in the year 1700, Bienville told him what had occurred. Iberville became very uneasy, for he felt that the arrival of the English vessel on the Mississippi proved the truth of the report that England would try to settle Louisiana. He wished to follow his own ideas with regard to Louisiana; but the government, though interested in its settlement, left the matter in the hands of Pontchartrain, who agreed with Iberville that the only way to hold the country was to people it; yet they did not agree upon the way of doing this.

Iberville had seen what the difficulties would be and what the new settlements would need, to make them a success. He was a man with a great deal of common sense. His plan was to settle the country with people who had a little money, who had worked and were willing to work. With emigrants of that kind he believed the colony would soon be able to take care of itself.

But Pontchartrain would not listen to such a plan. He told Iberville to pay a great deal of attention to the tamino: of wild animals for the sake of their wool, to see if it were possible to teach the Indian girls to raise silkworms, to find out if there were valuable pearl fisheries in the Gulf, and to remember that the most important thing was the discovery of mines. To make sure that the last was attended to, a geologist, Le Sueur, was sent along with Iberville, with orders to search for a copper mine reported to be on the upper Mississippi. Iberville had not seen any gold or silver or copper in

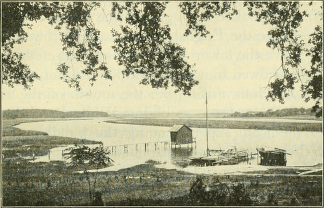

Copyright, iqoi, by Detroit Photographic Company.

Site of Old Fort Bayou The fort was built by Iberville on the east side of Biloxi Bay

Louisiana, and he knew that De Soto had found none. Nor did he liave much faith in the geologist's finding any. Yet he obeyed orders as nearly as he could, and in the meantime was sowing a crop of sugar cane and giving the Indians some orange, cotton, and apple seed to plant.

Next he looked for a good place to build another fort. Since the English were so active, it would not do to leave the lower Mississippi unprotected. The Indians showed him a place which did not overflow, about fifty-four miles from the mouth of the river. Here the new fort was built. While Iberville and Bienville .were superintending the building of the fort, their attention was attracted to a canoe cominor rapidly down the stream and steering for the bank where they stood. One of the men leaped ashore and introduced himself as the Chevalier de Tonti, the friend of La Salle. They were very glad to see him. He had heard the French were in Louisiana and had come to see if it were really true. He was eager to throw himself into the work, and offered his services to Iberville, who very gratefully accepted them. Iberville needed some one to visit the Indian tribes whom the English were urging to attack the tribes friendly to the French.

Tonti was therefore sent on a visit to the fierce Chickasaws, while Iberville himself visited the Natchez Indians. Iberville was greatly delighted with the country of the Natchez. He found them more civilized than any other Indians he had seen. Their chief was called the Great Sun, and his home was on a mound overlooking the villages of his subjects, which were dotted over a beautiful plain. This Great Sun was a very important person indeed. He chose his servants and his little son's playmates from the most aristocratic families. If a Great Sun died, his servants were strangled at his grave to wait on him in the next world; and if his boy died, the playmates had to follow their little master. So, while it was a great honor to be chosen to wait on royalty, it was an honor sometimes dearly paid for. The Great Sun could have any of his people put to death if he did not like them, and they supported him, while he did not work at all.

When the royal pantry was empty, an invitation was sent to the people to attend a great feast in the king's home. This seems a queer time for such an invitation, but the Natchez Indians' ways were not like ours. All the company came loaded down with something to eat; and after everybody had eaten a good dinner, there was enough left to last the Sun's family a long time. When food again gave out in the king's house, another invitation would be sent to the people to bring provisions to the royal household.

The next tribe the Frenchmen visited was the Tensas, among whom they saw something which they never forgot. They were awakened one night by a terrible hailstorm, such as we sometimes have in early spring, and were told the temple had been struck by lightning. When they reached the place, they saw the " medicine man " — who in every tribe was half doctor and half priest, and who looked more like a demon than a man — standing before the blazing temple and shrieking above the howling wind to the squaws that their god was angry and would not be at peace with them until they had offered their papooses (as the Indian babies were called) to him through the flames. Several mothers rushed up, and, throwing their little ones into the fire, stood by watching the flames wrap around the writhing, tender little forms. Iberville tried to make them feel the horror of the thing, but the women believed they had won a place in the happy hereafter by so great a sacrifice.

The Tensas' village was as far as Iberville went. Here, putting the expedition under the command of Bienville with instructions to explore the Red River country, he returned to Biloxi.

Questions. — I. How were the English prevented from settHng on the Mississippi?

2. Who was Bienville?

3. Tell the story of Tonti as given in Chapters III, VI, and VII.

4. What wise thing did Iberville do in the matter of starting crops?

5. What Indian customs have you learned about in this chapter?

CHAPTER VIII

BIENVILLE VISITS THE RED RIVER COUNTRY

Bienville proceeded to visit the Red River country. If he and his Canadians had not been hardy young fellows, they would have turned back after the first day's march. They moved steadily toward the north against a piercing March wind, with a sleety rain dashing into their faces. A great part of the time they traveled through water up to their waists. The Indians thought this was too much; they said they did not want to walk through ice water all day, and went back. The Frenchmen laughed and sang and got up into the trees to sleep and eat and dry themselves, and then went gayly on. They wanted to impress upon the Indians that they had come to stay, and were not to be put out by such small matters as cold winds and ice water.

It was owing to Bienville's courage, perseverance, and tact that his men stuck to him. They went as far as Natchitoches, and the knowledge orained of I that part of the country was of great value to the French. Iberville, sick with fever, again sailed for France. Before he left he put Bienville in command of the new fort on the Mississippi and Sauvole in command at Biloxi. As time passed the two young commanders did little more than hold the forts. No new settlers came; those already there had no money and could do nothing without the help of France. Bienville occupied his time in having his fort kept in fine condition and in seeing to the planting and working of vegetable gardens.

Sauvole was having a harder task. His men were more difficult to control; they had left Canada through the love of adventure, and liked to hunt, drink, and play cards; but they would not work. What little had been planted a long drought dried up; water, too, became very scarce, and this naturally caused sickness. Sauvole nobly devoted himself to nursing the worthless, trifling men, and lost his life in doing his duty.

Now the charge of both forts fell to Bienville. Many calls for aid were made upon him, but he managed economically and wisely, and was able to keep his own people from starving and to satisfy the Indians with food and presents.

Iberville returned to Louisiana in 1701. He tried to get Spain to cede Pensacola in Florida to France, but Spain refused to do so, and warned the French to keep away from her possessions. Iberville was determined to have a port on the Gulf coast, and since he could not get Pensacola, he ordered Bienville to build a fort and start a town

on the Mobile River and move the colony from Biloxi to Mobile. Iberville superintended the building of the fort and the laying out of a small town, and made arrangements for the landing of emigrants on what is now Dauphin Island.

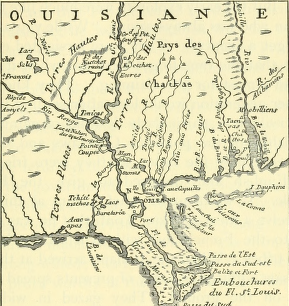

Map of the Country Around the Mouth of the Mississippi

From a map made in 1758.

Iberville looked upon what had been done with great satisfaction. The French now claimed a stretch of country encircling the Gulf from Mobile Bay to Matagorda Bay on the coast of Texas, where La Salle had landed. It may seem strange that they should want so much territory when they were able neither to work nor to settle what they had. But the early explorers were much like the old woman who was always saying, "While you are getting, get a plenty." They were farsightecl enough to see that the time to get land was when it might be had almost for the claiming. They knew that another generation would look after settling it.

Iberville was particularly desirous of gaining the friendship of the powerful Choctaws and Chickasaws, especially the latter, as they were friends of the English and disposed to give the French trouble. It was a great relief to him at this time to receive a message from Tonti that he was on the way to the French fort with chiefs from both of these tribes. When the Indians arrived at the fort, they saw a glittering array of presents spread temptingly on the ground. They gazed in wide-eyed astonishment and admiration. So much powder and balls, so many guns, they had not dreamed were in the world — to say nothing of the shining hatchets and knives, and gayly colored beads and curious trinkets.hey lost no time in getting out their peace-pipes, and made all the promises Iberville asked of them. But the red man in some re? spects is like his white brothers — sometimes he does not keep his word.

War had again broken out between France and England, and Iberville could not remain longer in Louisiana. He was needed to fight for France on the sea. He knew the war would cost a great deal of money and that France would need every cent she could raise, yet he was determined that no matter what happened, he would bear his colony in mind. Iberville was too level-headed to believe that soldiers in a fort and geologists with wild schemes of discovering gold and silver mines would ever make strong, permanent settlements. He knew that women were needed to make homes, and promised Bienville that when he returned to France he would lay this need before the government. He then sailed away, leaving Bienville in command — a governor only twentytwo years old. Iberville knew his young brother had learned much from experience, was firm, quiet, and strong-willed; and he believed that Bienville would prove worthy of the trust placed in him.

Questions. — I. What two forts did the French colonists have in 1700?

2. Tell something of life in the colony at this time.

3. Where was the next fort and settlement made?

CHAPTER IX

BIENVILLE AT THE HEAD OF THE GOVERNMENT

To be the sole representative of royal authority in the colony was a big responsibility to rest upon the young governor. Just now things were happening which made it important that Bienville should not make mistakes. It meant a good deal in those days to the colonies that France and England were at war, for when the mother countries quarreled, the children across the water took up the fight. English vessels cruising about the Gulf interrupted the flourishing trade which had sprung up between the colony and the West Indies, and, moreover, kept Bienville in constant fear of attack. The Indians who were allies of the Ensflish were also made bold by the nearness of their friends, and often attacked the Indians friendly to the French.

You have noticed, perhaps, that the French were on o-ood terms with most of the Indians. Though Bienville was just as fair in his dealings with them as ever, yet he now had a powerful rival in the English traders, who appealed to the Indian's self-interest — an instinct very strong in all of us. The English traders were everywhere going among the Indians, selling them better and cheaper goods and trying to draw them away from the French. When they could not do this, they encouraged the Indian allies of the English to attack the French Indians and murder the French missionaries.

Bienville, though he had few men and very little money, was forced to take sides. To keep his Indian friends, he must protect them. This led to a petty warfare which lasted for many years, was very annoying, and cost a good deal of money. Bienville probably managed as wisely as any one could have done in his place. It is wonderful that he was able to keep his little settlement from being wiped out, as the Indians could see how few men he had. Once when he was trying to impress a tribe with the greatness of the French nation, a chief said, " If your countrymen are as thick on their native soil as the leaves of our forests, how is it they do not send more of their warriors here to avenge the deaths of those fallen by our hands?"

Truly this year of 1703 was a gloomy one.

Bienville

Through Iberville did not forget his promise and sent over a ship laden with good things, — and twenty-three fresh-faced girls to become the wives of those young men, — yet the ship was not wholly a blessing. It had touched at Havana and brought into the colony yellow fever. Many of the people died, among whom, and the most deeply mourned of all, was the courageous man and true friend, Tonti.

From this time on Bienville had to bring to bear all his courage and self-control. The young women were disappointed, and did not hesitate to say so. They had been accustomed to the ordinary comforts of a city and had not the slightest idea of the meaning of pioneer life. When they were taken to log cabins, furnished with homemade furniture, and had nothing for breakfast, dinner, and supper but parched corn, they said that they had been deceived and that while the men might eat such stuff, they would leave on the first ship if better food were not given to them. As Bienville was a young bachelor, and most of his life had been spent among men, he must have been at a loss to know what to do.

This affair, however, was not so serious as the complaints and intrigues of some of the colonists who were jealous of young Bienville. They criticised Bienville and interfered with his authority. The quarrel grew until it was not long before everybody in the garrison was taking one side or the other.

Finally the enemies of Bienville wrote to France that Bienville was selling to the Spaniards the stores sent for the use of the colonists and putting the money in his own pocket. You know without beino^ told that Bienville would not bear this insult patiently. He wrote back to France, bitterly denying the charge, and accused the men of lying maliciously. Several years passed and every ship from Louisiana carried back accusations and denials, until at last Bienville was dismissed from office. It seems strange that the word of unreliable men should have been taken instead of Bienville's. It seems, too, that his interest in the colony and his services should have counted for something; but then, as now, a great deal depended upon political influence, and Bienville had none. Iberville, once powerful at court, had died. His friend, Count Pontchartrain, was also dead. The new minister, the new Count Pontchartrain, was a very different man from the old count, and neither knew Bienville nor felt any interest in him.

A new governor, who, however, died on the way, and a new commissary, Diron D'Artaguette, were sent out. Bienville, like the brave man and honorable gentleman he was, wanted to sail immediately for Paris and himself answer to the charges made against him, but D'Artaguette told him he v/ould be needed until a new governor had been appointed. D'Artaguette had a kind motive in this.

Though he did not tell Bienville, he had been ordered to look strictly into his conduct, and if the charges against him were true, to send him a prisoner to France.

D'Artafjuette did not want Bienville to oro to France until he had written a full and true account to the minister, for the royal commissary knew that it was easier to get into a French prison than to get out. He found nothing wrong with Bienville's administration; on the contrary, he found that Bienville had managed remarkably well with so little money. Instead of making money, neither Bienville nor his brothers had received their salaries for some time.

D'Artaguette saw that the colony was very poor; no emigrants were coming in; and through lack of money nothing was done to develop the country. Yet he knew that money had been appropriated for the colony. Where was it.^* After reading D'Artaguette's report, the French government discovered that the money had been stolen by officials before it ever left France.

Three years passed, and no ship and no governor came to the colony from France. The colony had either to starve or take care of itself. On account of overflows the fort on the Mobile River was removed to the site of the present city of Mobile; and to keep all from starving, Bienville sent some of the young men to live among the Indians. They hunted with the young braves, and at night danced and sang with the Indian girls, and had such a good time that they were not wilHng to go back to disciphne. If work were as much as mentioned to them, they ran off to the woods.

The future of ony had never seemed so gloomy, for never before had the mother country so utterly neglected it. But France had not forgotten the colony. She herself lacked money at this time; so Pontchartrain was looking about to see how he could best get rid of troublesome Louisiana.

Questions. — Tell about Bienville's first term as governor (1702-1712) :

I. Relations with the Indians.

2. The coming of women from France.

3. The yellow fever epidemic.

4. Bienville's enemies and the investigation of his government.

5. Hardships of life in the colony.

CHAPTER X

ANTOINE CROZAT

At this time there lived in France a man named Antoine Crozat. He had once been a poor country boy. He had been fortunate enough to have a chance of getting a very good education. As a boy he wanted to do things in life — something that his kinsfolk and comrades never dreamed of. He was not satisfied to spend his life as his forefathers had done, plodding along in the same old way.

When Antoine grew to be a man, he went to Paris and became a merchant. It was not many years before he was rich and lived in a fine house. He had servants and carriages and horses, and when he became very, very rich, he was presented at the court of the great King Louis XIV. He wore velvet and satin, with diamond buckles on his shoes, and sparkling rings on his fingers, and his wig curled in rows of glossy curls.

Now he was a fine gentleman indeed ! Even princes of the royal blood paid him attention. They asked him to dine with them and were so friendly as to borrow money from him. You think, perhaps, that he was perfectly happy; but not so.

There was something else he wanted. He wished to own large estates, for if they were only large enough, he might become a nobleman himself.

Pontchartrain knew Crozat's ambition and unfolded to him a fascinating scheme of chartering Louisiana. Pontchartrain told him that he could own estates in that province broader tlian those of any prince, and the mines would bring him such wealth as to make kings seem paupers.

Crozat was dazzled at the brilliant prospect before him. He had great confidence in himself; he had made his life a suecess so far; why should he not continue to do so? /Therefore a baro;ain was made between him and the I government in 1712. As some writer has said, Louisiana became through this bargain a royal farm, with King Louis the landlord and Crozat I the farmer. And the farmer felt hopeful of maky lying a fine crop.

Now this was the bargain: No one but Crozat should be allowed to trade in all that immense country between the Alleghany Mountains on the east and Mexico on the west, and from the Great Lakes on the north to the Gulf of Mexico on the south. F'or trading purposes he could carry whatever he pleased from France and trade in any way he liked. If other people should be caught trading in Louisiana without his permission, the king's soldiers would seize their goods. No one else could have factories in the colony. He alone could make silk and woolen and leather goods. He was also given the sole right to trade in furs, excepting beaver skins. This exception was made because the Canadians traded in beaver skins, and as they were Frenchmen, they must be protected in this trade. The last and most gracious favor of his Majesty to Crozat was to give him all the land he could cultivate and allow him to work the mines. He naturally could not expect to keep all the wealth that it was thought the mines would produce, and considered it generous that the king should reserve only one fourth of all the gold and silver found, and one tenth of the precious stones.

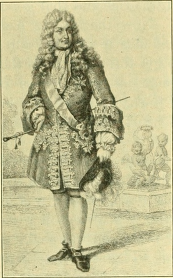

King Louis XIV

Crozat on his part was to bring over two shiploads of settlers every year, and after nine years was to pay the expense of all ofificers and soldiers stationed in the colony to protect it.

This indeed seemed to be the grand opportunity of his life. If Crozat had known as much about the geography of this country as you children do, he would have scratched his head and thought a long, long time before undertaking so much.

That Crozat's interest might be better served, it was thought wise to appoint a new governor and also a council which would govern the colony by the laws of France. But a mistake was made in the appointment of a governor. The new governor, Cadillac, belonged to one of the old families of France, was pompous, narrow-minded, and quarreled with every one who did not think as he did. He quarreled with one man because he got drunk, with another because he was a fool, and with Bienville because he did not take the holy communion.

Because Dauphin Island was the first land in Louisiana that he saw, Cadillac judged the whole country from that little spot, and said it was a miserable country with a few plum trees bearing two or three plums to a tree. When the settlers came to him to divide the land, he told them to take what they wanted, as none of it was of any account. He turned up his aristocratic nose at Bienville and his friends, and called them vagabonds and ruffians, without respect for law or religion.

Now this was the man who, as the governor, was supposed to work for the good of the colony as a whole. Crozat was too wrapt up in his schemes for making more money to take a broad view of the situation and to see that even for his own success it would be better to unite the colonists so that all would act together. To do this he simply needed to be just and give the colonies an interest in the enterprise. Instead of doing so, he attached Cadillac to himself by giving him a share in some mines, and ignored Bienville; but Bienville, of all men, was in close touch with the colonists and had their confidence. He felt very badly because he had been put aside for strangers.

Copyright iqoi, by Detroit Photographic Company.

Bay St. Louis On this coast one of the earliest settlements was made.

Bienville, sick at heart, asked to be given a command in the French navy, but Pontchartrain, knowintx how well he could manasre the Indians, ordered him to remain in Louisiana. He made no effort to hide his feelings, and thus the new administration began with almost an open quarrel.

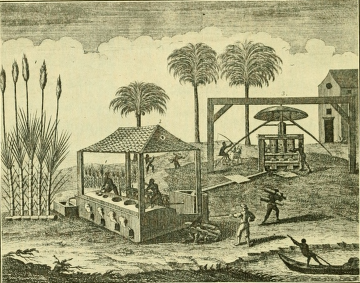

Crozat found it a difficult matter to make money from the bargain, which on paper had seemed so tempting. The land to be worked had to be stocked with everything needed on a big plantation, and, though he had been given the right to bring over from Africa a shipload of negroes every year to work the crops, these negroes must be fed and taught to work. Factories had to be built, and fitted with expensive machinery, and the raw material raised for use in the factories. As for the mines, there were none.

Crozat had hoped to establish a liv'ely trade with the Spaniards in Florida and Mexico, but Spain was now friendly to England and unfriendly to France, and consequently forbade the Spaniards in her colonies to trade with the French in Louisiana. The trade that Crozat could carry on with his own colonists amounted to little. They were poor and were scattered throughout the province. They preferred to trade with the Indians and the English, who gave better bargains. This trade was illegal, and was carried on without Crozat's knowledge.

Crozat at last found that he could not pay the expenses he had agreed to pay, and when one of his ships came in loaded with expensive goods, he had to give the cargo to the people for wages. But what could they do with such costly things ? They wanted money with which to buy something to eat. Their dissatisfaction added greatly to the troubles of Crozat, but before giving up, he determined to make one more effort to succeed.

Questions. — I. State the extent of the " farm " that was leased to Crozat.

2. What privileges was he given?

3. What was he required to do?