Strang and Moore.

“Longfellow's Evangeline.”

NOTES TO THE NEXT GROUP

- Start proofreading at STOPPED HERE. It's p. 62 in the .pdf.

- Fix the list at the beginning.

- Correct typos, Change to italics where needed, and format footers

- Integrate the footnotes.

Longfellow's Evangeline

Longfellow, Henry Wadsworth, 1807-1882

Strang, H. I. (Hugh Innes), 1841-1919

Moore, A. J

LONGFELLOW'S EVANGELINE

Edited by Strang and Moore.

NOTE.

At the request of several teachers we have prefixed to this edition a topical synopsis of the poem, with suggestions as to compositions based on it, and also a few general questions on the poem as a whole. For these we are indebted to the courtesy of J. M. Field, B.A., Modern Language Master of Goderich Collegiate Institute.

The topics marked with an asterisk in the synopsis will serve as excellent subjects for composition.

EVANGELINE

The scene is laid. The tragedy is anticipated. The theme of the tale is the beauty and the strength of woman's devotion.

- Grand-Pré. (Lines 20-57.)

- a. Benedict Lafontaine. (58-64.)

- Evangeline. (65-81.)

- Their home. (82-102.)

- a. Basil the blacksmith and Gabriel (103-122.)

- The smithy. (123-133 )

4. The children play and grow up together. (134-147.)

II.

*1. Indian summer. (148-170.)

*2. A summer's evening on Benedict's farm. (171-217.)3. The arrival of the English ships. (218-266.)

III.*1. The notary and his story. (207-329.)2. The marriage contract. The la.st evening together. (330 381.)

4. The feast of betrothal (382-419.)

2. The proclamation of the English. (4'r'0-459.)

3. The priest calms the tumult of his people. (460-486.)

4. Evangeline ministers to the sad and mournful hearts of the people.

(487-523.)

V.

1. The scene on the eve of the exile. (524-612.)^2. The burning of Grand-Pré. (613-635.)

3. The death and burial of Benedict. (636-660.)

4. The Acadians go into exile. The confusion of embarkation. (661

665.)

ii

EVANGELINE. Ul

Part the Second.

#

1. A Break in the narrative? years have passed since the exile. (1-27.)

2. Evangeline, separated from Gabriel after embarkation, wanders

over the land in search of him. ('28-52.)

3. Her heart is fortified Ly the words of the priest. (53-75.)

II.

*1. Evangeline and Father Felician accompany a band of their

countrymen down the Ohio river. (76-1(31.)*2. They miss Gabriel during the night. (IG2-17G.)

3. Evangeline's vision. (177-197.)*4. Sunset. (198-222.)

III.*1. The home of Basil the herdsman. (22.3-262.)2. Basil gives news of Gabriel, and tells how they must have missed

him. (263-293.)*3. Michael the fiddler. (294-300.) .*4. The exiles' re-union and feast. (S00-3;"5.)

5. Evangeline, full of thoughts of her lover, goes apart, where she

gives herself up to an ecstasy of despair and hope. (350-393.)

6. They continue their search. (394-412.)

IV.

1. The far West. They follow Gabriel's footsteps unceasingly, but

without overtaking him. (413-450.)

2. The Shawnee woman. *Her tale. Sympathy. (451-499.)*3. The Indian mission. (500-541.)

4. They pass the autumn and the winter at the mission, and leave

in the spring when they receive news of Gabriel. Again she meets with disappointment. (542-573.)

5. Evangeline becomes faded and old in the search. (574-586.)

1. Back to Philadelphia, where she had landed years before, an

exile. Her heart is as true and devoted to her lover as at that time. (587-620.)

2. She becomes a Sister of Mercy. (621-632.)

3. The plague. She nurses the stricken. She discovers Gabriel

among the patients. His death. (633-715.)

4. The lovers sleep side by side in nameless graves. They have

found rest after their wanderings. (716-724.)

5. Evangeline is remembered in her native land. (725-end,)

IV EVANGELINE.

The topics suggested as subjects for composition may be further out-lined somewhat as follows :

Grand-Pré.

1. Its position geographically, in general and in detail, with special

reference to picturesqueness.

2. The surrounding physical features? meadows, dikes, Blomidon,

enclosed valley.

3. The farms, houses, and the village street.

4. The inhabitants, their dress, etc.

5. The priest.

6. The simple, happy, and peaceful lives of the inhabitants.

THE VILLAGE SMITHY.

1. The exterior.

2. The blacksmith and his apprentice.

3. General features of the interior.

4. The picturesque elements,(a) The sounding anvil.

{h) The flying sparks and the blazing forge.

5. The horses and the operation of shoeing.

6. The picture remains in the memory as a vivid scene of the

recollections of childhood.

GENERAL QUESTIONS ON THE POEM.

1. Draw a map illustrating the wanderings of Evangeline and

Father Felician.

2. What would have been the effect on the tale if Longfellow had

brought it to a happy issue ? Would it have improved it or marred it ? Give reasons.

3. Discuss Longfellow's appreciation of humor from the following:(rt) Haggard, and hollow, and wan, and without either thought or

emotion.E'en as the face of a clock from which the hands have been taken.{b) Sweet was her breath as the breath of kine that feed in the meadows.

4. Show how the poem presents good opportunities for the dis-

play of melancholy hopefulness and cheerfulness.

5. By what means has Longfellow idealized the story of Evangeline?

6. (a) What are the historical facts in connection with the expatriation-

of the Acadians ?{b) To what extent has Longfellow been unjust to the British ?(o) Was his reason poetical or due to prejudice ? Explain.

LIFE OF LONGFELLOW

Longfellow was of New England stock. A John Alden and a Priscilla Mullens,1 who came out together in the Mayflower,by their union became the ancestors of Zilpah Wadsworth, the poet's mother. About sixty years later a William Longfellow,from Yorkshire, like the Puritan Priscilla first mentioned,settled in Massachusetts, and was the ancestor of Stephen, the poet's father. His mother's people were at first in no way distinguished, and the earlier Longfellows had but in difierent headpieces, but as the streams of descent converged towards our poet, the refining influence of education and wealth, or the mysterious power of natural selection began to be felt. Thus in the times of the Revolution one grandfather, Peleg Wads worth,of Portland, in the state of Maine, figured as a General, active in the war, while about the same time, and in the same town,his other grandfather, Stephen Longfellow, became a Judge ofCommon Pleas.

Here in February, 1807, Henry Wads worth was born, the second of a family of eight. His father, a graduate of HarvardLaw School, a refined, scholarly and religious man, bestowed every attention on his children's education and manners. His mother knew but little else than her Bible and Psalm book, but was esteemed by all as a lady of piety and Christian endeavor,and transmitted her gentle nature as well as her handsome features to her favorite son. He grew up, a slim, long-legged lad, quite averse to sport or rude forms of exercise, and from his earliest school going was studious in the extreme. It is in-

teresting to note his favorite books. He loved Cowper's poems, Lalla Rookh, Ossian, the Arabian Nights, and Don Quixote, but above all he was enamored of the Sketch Book. In the few boyish attempts at verse-writing which are preserved we can scarcely see either the fruit of his reading or the germ of his future excellence. The child was not in his case the promise of the man.

Longfellow carried his studious habits, his shyness, and his slowness of speech to Bowdoin College.2 Some of his class-mates there were afterwards men of note, e. g., Abbott, the historian; Pierce, the politician; and Cheever, the preacher and author ; but undoubtedly the most eminent of all was NathanielHawthorne. Longfellow graduated with distinction when but nineteen, and was one of the orators of his year. Just here an incident occurred which shows how often mere chance has the shaping of a career. At this final examination a leading trustee of the College was so taken with Longfellow's translation of an ode of Horace, that he proposed him for the new Chair of Modern Languages, then just established. The Board agreed,his father was willing to bear the expense, and so this youth of twenty was shipped off to Europe to fit himself by study and travel for his new duties. During his college course he had contributed some twenty poems to the pioneer literary magazines, the Monthly Magazine and the Gazette, but these, although marked by purity and graceful language, certainly showed little originality or scope of fancy.

He remained in France, chiefly in Paris, and vicinity, eight months, a close student of the French language and literature.Thence, in February, 1827, he set out for Spain, on a similar errand, and while in Madrid he made the acquaintance of Washington Irving, then engaged on his life of Columbia. We next find him at Rome (December), and a year after in Ger-many. Letters from ail these places were frequent, but it is

something of a wonder that they are of so little worth, and contain no description, no observations of any acuteness or value. Probably language-learning consumed his time, and he trusted to his retentive memory for the rest. Years after, these memories of travel are reproduced in both prose and poetry,and seem to lose but little in vividness by their delayed utterance. At length the traveller-student returned to his native land, and became, at the age of twenty-two, Professor of Modern Languages in his own Alma Mater. And there is little doubt that at that time and in that walk he was the beet furnished Professor in all America.

Behold now Longfellow a full-fledged professor, amiable, of gentlemanly manners, handsome, and just turned twenty-two. Industrious, too, neglecting no interest of his pupils, and as a natural consequence from so many virtues greatly beloved of all Just two years after his assumption of the professor's robe, he married Mary Potter, the daughter of his father's most intimate friend. Then followed a few years of perfect happiness,of congenial labor,3 of scholarly associates, and with the companionship of a beautiful and intelligent woman.

There seems to have been leisure also for production, for in 1833 appeared his first volume, a translation from a dull Spaniard. But in the same year appeared something of much more inter-est, the first part of Outre-Mer, A Pilgrimage beyond Sea. In this pleasant and at the time very popular book, we find the record of his European tour.

The influence of the Sketch Book is apparent, and he openly enough imitates both Irving and Goldsmith. The style,indeed, is as graceful as Irving's style, but the descriptions are more downright, and wanting in his delicate touches, while his humor is almost entirely wanting. However devoid of interest Outre-Mer may now be, after the lapse of nearly sixty years,

when half the descriptions would not be true, and when the moralisings would be thought commonplace, it had a consider-able effect on Longfellow's fortunes.

At the end of 1834 he was offered a similar Professorship at Harvard, at the largely increased salary of fifteen hundred dollars. As he was weakest in German and the Teutonic languages generally, he was allowed a year's travel before entering on his duties, and his wife and he set out in the spring of 1835. In Tendon, during a three weeks' stay, they visited a few celebrities, Carlyle the chief ; thence they went to Stockholm and Copenhagen, and afterwards to Amsterdam, where he again became the earnest student of languages. It was at Rotterdam that Longfellow experienced the first and greatest sorrow of an exceptionally fortunate and favored life. Here his wife fell ill and died, after a lingering and painful illness.Of a nature reticent and retiring, that shrank from the exposure of his inmost feelings, the depth of the loss to him we can never fully know, but that she ever remained a sad and tender memory we have ample evidence from his poems.4

In the spring he went on to Heidelberg, where he made the acquaintance of several German literati, and for the first time met Bryant. Some pleasure he took with those friends about the old University town, but the bulk of the time was dogged study, given to Goethe, Tieck, Richter, and other authors.In the summer we find him in the Tyrol, in the autumn at Interlaken, and in December of the same year (1836), back atHarvard, entering on his duties.

He took up lodgings at Craigie House, once the abode ofGeorge Washington for some months after the battle of Bunker's

H even occupying his very room. Here after a whileHawthorne renewed his acquaintance, sending him a copy of his Twice-told Tales, which Longfellow very kindly reviewed in the North American. At Harvard, Longfellow had less to do than at Bowdoin, and had therefore more leisure for purely literary ways? His lot was, indeed, a fortunate and enviable one; a long life still before him, perfect health, an honorable and not burdensome position, a comfortable home, no money anxieties, and a few scholarly men of his own age5 to give him counsel and perhaps suggestions. This last was the stimulus that Longfellow needed. He resumed his verse making, submitting it from time to time to the kindly criticism of his friendsThe first published was Flowers, and the second the Psalm ofLife, July, 1838,6 appearing anonymously in the Knickerbocker Magazine. In 1839 a volume was issued with the title Voices of the Night, including the above and the other pieces usually so headed in the editions of his poems, together with his earlier poems and a few translations.

A few months previously he had published Hyperion, his prose romance. The hero, Paul Flemming, is no doubt himself,the heroine, Mary Ashburton, was with as little doubt a MissFrances Appleton, whom he had met when at Interlaken. So evident is the suggestion and portrayal of scenes and incidents occurring only in her company that the poet's mind u plainly disclosed, and clearly presages some coming events. Indeed,the spring and motive was so apparent m to give rise to the charge of indelicacy.

He has managed in this book to impart a great amount of local colour by criticisms and quotations from German authors

and renderings from German song. Hyperion was no doubt a bid for the primacy in American prose fiction. With more narrative than Outre-Mer it is not nearly so good as to style ; is as subjective as the former is objective, and is too frequently moralising and sentimental. Hyperion is still read and is still interesting, and its strictures on men and books are still of some value as mere literature. But of German philosophy Longfellow had no grasp, and he may be said wholly to ignore those great social and scientific trends of human action and thought which now engage to some extent the pen of every great traveller and novelist.

His diary shows us that several schemes of future works were at this time developing in the poet's mind, but we must leave the names and the consideration of these to another place. In 1842 he made n trip to England on the score of health, and while there visited Dickens, and otherwise thoroughly enjoyed himself. While returning he wrote on ship-board his poems on Slavery, published this same year, of which the Slave's Dream and the Quadroon are the strongest and best. Next year came the realization of Mary Ashburton Miss Appleton had been seriously offended by the too evident references of Hyperion, but she finally succumbed to the combined attractions of his handsome person, his assured position,and his growing fame.

The bride's father, who was a wealthy man, did not allow his daughter to go unportioned. He bought the Craigie House and estate, and presented them to the newly married couple. For the rest of his life Longfellow was thus in easy circum-stances, not dependent on his professorship or the sale of his works. Few poets have had their lines cast in such pleasant places?an ample fortune, a beautiful young wife, the prospect of gaining an assured place in the affections of his countrymen,and all these at the early age of 36. Yet his innate modesty still remained, and stranger still, his industry did not slacken.

In the same year as his marriage Longfellow published the Spanish Student, his best dramatic poem. The plot is a commonplace one. The heroine, a Gypsy dancer, is unnatural in her want of passion; the hero, a student madly in love with the aforesaid maiden, is spiritless and quite too metaphysical and instructive in his conversation. There is no deep emotion in the play, and as Longfellow has nowhere else displayed any sense of the comic or ridiculous, he has been suspected of cribbing his best character.7 Some fine descriptions, some moral reflections,some pretty songs8 adapt it well enough for parlor theatricals, but there is not strength enough in it to make a stage success.

In 1845 appeared a work written to order, The Poets and Poetry of Europe, four hundred and more translations from a dozen different languages, a few by Longfellow himself, as were also the critical introductions. In November of the same year he began the Old Clock on the Stairs. A fortnight later his diary says: " Set about Gabrielle, my idyl in hexameters, in earnest. I do not mean to let a day go by without adding something to it, if it be but a single line. Felton and Sumner are both doubtful of the measure. To me it seems the only one for such a poem." After several changes of name it was finally christened Evangeline. The discussion of this and of some other pieces in his volume of 1846, will be found else-where. In 1849, two years after Evangeline appeared, he published Kavanagh, a tale of New England life, about which no one ever has been or ever will be in raptures. The scenes are true enough, but in the humdrum affairs of a country village,there are not many worth depicting. Longfellow seems to have been quite incapable of understanding that a plot is one great essential to an interesting story. Next year, however, his new volume of poems contained two pieces which would have atoned

for a much duller tale than Kavanagh namely, Resignation and The Building of the Ship. This last, modelled as to form on Schiller's Song of the Bell, is one of the noblest of Longfellow's poems, and the concluding lines* have always been enthusiastically received by American audiences.

The Golden Legend (1851) is of the 13th century, and attempts the reproduction of Mediaeval machinery. Bands of angels, troops of devils, Lucifer himself, monks and choristers and minnesingers are the dramatis personæ. A Mystery or Miracle play is introduced, as are also a friar's sermon, and here and there Latin hymns. As an imitation and illustration ofthe superstitions, customs and manners of the Middle Ages, it must be considered as both accessful and instructive. As the burden of the play is the misleading of a Prince by the Evil One, and the treatment not dissimilar, it might almost be called a version of Goethe's Faust

Hitherto nearly all Longfellow's work had an Old World coloring, born of a student's natural reverence for the past, and his sojourn in land, richer in poetic material than his native America. But Hiawatha was distinctly a venture in a quiteoriginal field. Hope saw in the Indian only an object of com-passion ; Fenimore Cooper invested him with some dignity and other virtues; Longfellow found in him and his surroundingsmaterial for poetry ! But this was before the advent of the white man,

"In his great canoe with pinions,From th? regioiu of the morning.From the ihining land of Waboa."

before the use of firearms and firewater had begun their deadly work,

" When wild in native woods the noble savage ran."

It seemed fit to Longfellow that a new measure not hitherto used for the poetry of civilization should be the vehicle of its presentation. This he found in the great Finnish epic, the Kalevada. The Finnish poetry, like the early Anglo Saxon, had as a distinguishing feature, regularly recurring alliteration; and, in addition, what has been called parallel structure, i.e., the repetition in successive lines of a word or phrase at the begin-ning. Longfellow omitted much of the former, but madelarge use of the latter.9 He got his material from the Indian legends current in New England, and from Schoolcraft's Indians of the U.S. The song of Hiawatha, however, is not a continuous epic narrative, but a series of hymns, descriptive of episodes in the life of a mythical Indian chief, and the un-rhymed swinging of the short trochaic lines seems not ill adapted for the desired effect of unusualness and of being native to the soil as a purely New World product. Its success was marvellous. Vast editions of the poem were sold during the half-dozen years succeeding its first issue (1855). "The charms of the work are many; the music is deftly managed; the ear

does not tire of the short-breathed lines; no poet bnt Longfellow could have come out of the difficult experiment thus triumphantly; the poet has adorned the naked legends of Schoolcraft with all sorts of enrichment; it is highly improbable that the Red Indian will ever again receive an apotheosis" so beautiful as this at the hands of any poet."10

In 1867 when the Atlantic Monthly was launched, with JR. Lowell, as editor, Longfellow became a regular contributor, and in the succeeding twenty years contributed to it about fortypoems. In 1858 appeared The Courtship of Miles Standish, a second trial of hexameter verse. The stern Puritans and their sombre religious views furnish but indifferent material for poetry, and the poem, though not wanting in many beautiful lines and descriptions, is manifestly inferior to Evangeline. Four years before, he had resigned his professorship in order to give his whole time to literary labor. He continued to reside at Craigie House with his wife and children, a truly beautiful and loving household. In the summers they were to be found at Nahant,a pleasant seaside village near Boston. Here in a great framehouse of many rooms Longfellow passed the hot season, and sometimes entertained a friend, for he was much given to hospitality.

But in the full flower of his fame, and in the perfection of his powers, the second great calamity of his life overtook him. In 1861 his wife's clothing accidentally caught fire, and she was so severely burned that she lived but a few days. The poet, as in the case of his first wife, made no loud demonstration of grief, but, for that very reason perhaps, the shock to him was the more serious. From that day he rapidly and visibly aged; his wonted erectness and alertness sensibly diminished, some of his constant cheerfulness deserted him?even his diary and methodical habits of study were for a long time intermitted.

The plan of the Tales of a Waysids Inn (1863) was, no doubt, suggested by the Canterbury Tales, A landlord, astudent, and a Jew, a theologian, a musician, a Sicilian and a poet meet at a Wayside Inn, and each tells a story for the amusement of the company. The Landlord's Tale, Paul Revere's Ride, has always been popular; the others, while not equal to it, have perhaps not been appreciated in the degree they merit. The Prelude, describing the characters, is superior to the majority of the tales themselves in this respect, being, as some think, similar to Chaucer's Prologue.11

In 1868 Longfellow revisited the old world, and remained about a year and a half, visiting England mainly, but going as far as Italy. He was much lionized, as became the most famous and popular poet of America, Cambridge and Oxford gave him honorary degrees, all sorts of people were anxious to invite him to dinner, Mr. Gladstone shook him warmly by the hand, and even Royalty itself requested the honor of his company. He got back to Craigie House about the time of the publication of the last volume of his Dante.

He had been at work for years on this translation of The Divine Comedy. His success as a skillful translator had been very great. He had that artistic taste, that line literary instinct, that fastidiousness as to form and sound, which a goodtranslator must have. His work has been severely criticised on the score of its extreme literalness, which, indeed, is surprising in a verse translation. The beginner in Italian who usesLongfellow as a " crib," will scarcely need a dictionary. "This method of literal translation is not likely to receive anymore splendid illustration; throughout the English world his name will always be associated with that of the great Florentine."If Longfellow had attempted the other method of

*The scenes and characters are not imaginary, but drawn from the author's experienoe. The "Wayside Inn" was a tavern in Sudbury: its proprietor "the landlord;" the "musician" was Ole Bull, the noted violinist, etc.

translation, had ignored the mere syntax and word equivalence, had tried to reproduce the inner meaning and power of the great original, wherein is sounded the whole gamut of woe and despair, would he have succeeded! It is very doubtful; and competent judges have thought that he chose the wiser part. The measure of the poem is adopted, but not the rhyming; the impassioned spirit, the heat and the light of the Italian are wanting, but on the whole it is a most beautiful version.

The Hanjing of the Crane, 1874, is one of the most admired of his poems. As a beautiful picture of the formation of a household, and a poetic illustration of that family life which is said to be distinctive of the English races, we are sure no nobler example can be found. It is said to have been written in honor of Thomas Bailey Aldrich and his young wife. Many poems not mentioned in this short sketch also appeared in separate volumes from year to year. We can only mention Keramos (1878). With this appeared the last flight (the 5th)of his Birds of Passage. The first appeared with Miles Stand-ish, the second with Tales of a Wayside Inn, the third and fourth with other volumes. These Flights include some of the best of his shorter pieces, as On the Fiftieth Birthday of Agassiz, the Children's Hour, etc.

Ultima Thule was the title of his last volume (1880), which contained a selection of his latest and best occasional pieces. In the early days of March, 1882, he wrote his last poem (The Bells of San Bias). And on the 24th of the same month this most gentle, beloved, and popular of all the American poets was gathered to his fathers.

We may well say that by his death a nation was plunged into mourning. He was absolutely without personal enemies. His sweet and sunny nature had endeared him to the Americans, as did also the general character of his poetry, the incentives to manly endeavor, the steady encouragement to something better, higher, and purer, the unflinching faith in God's goodness

What short of the best could be the reward of this good and great man of blameless life, whose work had ever the loftiest aims? May we not well trust the burden of his own requiem, chanted as the bearers lowered his body to mother earth.

He is dead, the sweet musician !

He is gone from us forever !

He has moved a little nearer

To the Master of all music,

To the Master of all singing ! *

List of Poems referring to incidents in the poet's life:

Miles Standish. Psalm of Life.

Footsteps of Angels. The Old Clock on the Stairs.

To the River Charles. A Gleam of Sunshine.

The two Angels. My Lost Youth.

The Children's Hour. Three Friends of Mine.

Morituri Salutamus. From My Arm Chair.

In the Long Watches of the Night. Tales of a Wayside Inn.

XV. Hiawatha's Lamentation

COME BACK HERE LATER

LONGFELLOW'S LIFE AND WORKS.

AMERICAN LITERATURE.

ENGLISH LITERATURE.

1809

1812

18141816

18181819

18221826

18261827

1829

Born at Portland,Feb. 27.

Goes to Bowdoin.Graduates.

Goes to Europe?at

Paris.At Madrid, ai Rome

In Germany.Professor ak

doin.Marriage.

Bow-

1838 First Volume ? aTranslation.

1884 Professor at Har-vard.Outre Mer, RcNisitsEurope, death ofwile.

1836 At Harvard, 1837Psalm of Life.

18401841

184S

184S

Voices af the Night,

Hyperion.Wreck of the He*-

perut.Ekccehior.

Srd visit to Europe,

Poemt on Slavery.

Spanish Student,

2nd Marriage.

I Pottt and Poetry

\ ^ Surf.

Whittier, Agassiz, Haw-thorne, 6.

Holmes, Poe, b., Irving'eHist, of yew York.

ThanatopttM.

Motley, 6.Heavysege, b.

Lowell, Whitman, b.Bracebridge Hall, The Spy.

Dana's Biuxaneers, flal-leck's Ist vol. Cooper"!Prairie,

Irvinj^B Coluvibus.

Poe'8 l?t volume.

1832, Bryant's Ist. volume,Irving'i Alhambra.

Hourt of Idleneti, Mar-! mion (1808),I Gertrude of Wyoming,i Qtieeri Mab, Curte of. Kehama, Lady of LakeI (1810).

{ Dickens, Browning ft.I Thackeray, 1811, Child*i Harold, Cantos I., II.

Wav rley, The Excursion.

Old Mortality, Christabel,Lalla Rookh (1817).

Endymion, ChUde Haroldcomplete.

Rubkin b., Jvanho*, Prom-ethetis (Inbound.

Macaulay'8 Essay on MU-ton.

I Tennyson's Iflt toL 1880.

1832, Scott d.

Tennyson's 2nd vol. SartorReaartu*.

ITtpo Year* b^ore ih* Maai. | Browning's Para?tU%u.

1837, Ferdinand and Isch-

bslla, Twice Told Tales,

Sam Slick.Bret Harte, b., \yhittier'i

Ballads (1838).Bancroft's History of Col-

onizaiion.Emerson's Ist series oi

Essays, Lowell's 1st voL

of poema.CJhanning, d.

Conquegt of Mexioo.

Foe's Raven.

1837, Pickwick Paper t,Carlyle's Fr. Revolution.

Macanlay'i Lays, Loeksle%

HaU.Diokens' American Sotea.

Modem Paintert.CM^jle's CromveiL

CHRONOLOOICAL FARALLKL.

xix

L84e

1847

I860

18S1

185418551856

1857

18681861

1868

1864186818691.87018711873

18741876

1878

is?-<o

LOKOFKLLOW'S LiFl

ASD Works.

The Belfry of Bruget

Bvang0lit%4.Kavanoffk.

TheBuilditig^ftheShip.

71U Golden Legend.

Resits Professoiv

ship.Hiaicatfia,

Miles Standieh.

Death of 2n(l wife.

TtUee qf m WaysideJnn.

Dcmte, completed.

AMUIOIW LiTBB^miL

KMaLBH L4TIB.ATUBJL

Aftermath.

The Hanging of theCrane.

Kerainoe.mtima Thule,Death, Manjh 24.

A^assix at Harrard,

Bon's l8t vol. of poemi.

Uoeiee /rom un old

Manse.Conquest ^f Peru, Holme*

at Harvard , 1848, Big-

low Fapert,Poe d., Emereon'i Repres-entative Men, Irvug'e

Ooldsmith.Whlttler'8 Somjs of Labor,

Uncle Tom's Cabin. The

Scarlet Letter, Irving'!

Mahomet,House of Seven Gables,Coop?r, Webster, CUky,d.Lowell eucsceeda him.

Leaves of Grass, PresootVi

Ph^Hp II.Kmenjon'i Eng. Traits, The

Dutch RepublicA utocrat of the Bre<ikffistTable, Heavysege'g Saul.The Atlantic Monthly

hegun.Preecott d, (1869).

1860, The United Nether-land's, Sangf8t?r'8 Hes-perus.

WTiittier'i In War Time.

Hawthorne d., Heavysegfe'sJephtha's Daughter.

Emereon'a 2nd volume ofpoems.

Lowell's Undsr the Wil-lows.

Emerson's Srd volume ofE^ssaj's, B. Harte's Poems.

Lowell's My St'jdy Win-dows, Emerson'8 4th vol.

1872, Hohnes' Professorand Poet at the Break-fast Table.

Whittier's Mabel Martin,Agassis, d., Bancroft'sHist, of America, oom-pleted.

Emerson's Letters andSocial Aims.

Whittier's CentennialHymn, Gabriel C<>nroy.

Bryant d.. Motley d. aS77).

Lowell, Minister at London,

Em?r- I VmnOp #'s4r.

Th* Prinetu.

Macaulay'9 Hist, of Bn^i..

PendPHiiix, David Copperfield.

Wordsworth d., Jr* ^-'^h-oriatn. Ode on d*-^A ofWellington.

Henry ISsmoTuLThe NewcomeM.

Carlyle'g Frederick theGrent. ^lacaulvy, D?Quino>' d. (1659)1

Mrs. Browning d.

Browning'* Ring and theBook.

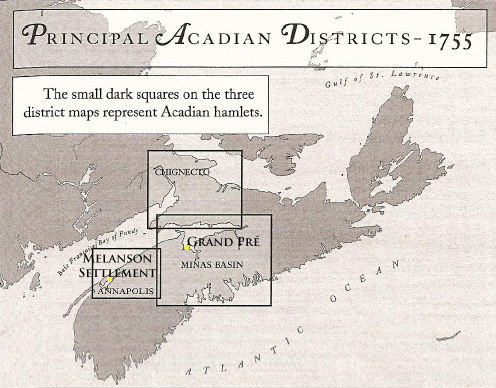

HISTORICAL GROUND WORK FOR EVANGELINE

In April, 1713, was signed the treaty of Utrecht. By its 12th article, all Nova Scotia, or Acadia, 'comprehended withinits ancient boundaries,' was ceded to the Queen of Great Britain and her crown forever. The term 'ancient boundaries,' at the time seemed explicit enough, but the limits of Acadia afterwards became a great national question, the English claiming all east of a line from the mouth of the Kennebec to Quebec as Acadia, the French restricting it to the southern half of the Nova Scotian peninsula. The inhabitants at the time numbered some twenty-five hundred souls, at the three chief settlements, Port Royal, Minas, Chignecto. They were given a year to remove with their effects, but, if electing to remain, were to have the free exercise of their religion, as far as the laws of England permitted, to retain their lands and enjoy their property as fully and freely as the other British subjects. But, British subjects they must be, and accordingly the oath of allegiance was tendered them. For some time there was a general refusal, because the Acadians rightly judged this carried with it the obligation of bearing arms against their countrymen. In 1730, however, Phillips, the then governor of Nova Scotia, was able to inform the Lords of the Admiralty, that all but a few families had taken the oath. But Phillips seems to have admitted, and the Acadians always afterwards assumed, thatthere was a tacit, if not expressed understanding, that they were to be exempt from serving against France.

Things went on with some smoothness for many years after this. But at last the thirty years' peace came to an end. France was lupporting Frederick the Great of Prussia, England

Maria Theresa of Austria. War accordingly recommenced in the Colonies, and the French had hope of reconquering Acadia. But although the news of the declaration of war reached them seven weeks later, the New Englanders were the first to act. La Loutre, the French missionary, who had been ever the inveterate enemy of the English, and the fomenter of discontent among the Acadians, stirred up the Indians to attack the English at Annapolis. But they were beaten off, till Gov. Shirley of Massachusetts, sent help from Boston. In that town there was great excitement, which took the form of volunteering against Louisburg. This town was the strongest place in America, Its walls of stone were nearly two miles in circuit, and thirty feet high, surrounded by a ditch eight feet wide, and defended by a hundred and fifty cannon. The entrance at the west gate was defended by sixteen heavy guns, while the island in the harbor mouth was furnished with sixty more. No wonder then, that this great fortress was regarded with fear and hatred by all the English in America. Yet, this 'Dunkirk of America' as the New Englanders termed it, was taken in exactly seven weeks, by an army of rustics from Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Connecticut, led by a man who from his youth up had been a trader, who knew absolutely nothing of military drill or organization, and had never seen a cannon trained on an enemy.

This expedition sent by Gov. Shirley, and headed by Gen. Pepperell, and consisting of 4,000 irien, 13 vessels, and 200 cannon, reached Louisburg on the 1st May, 1745. The garrison was completely surprised, and before they had recovered, the English were in possession of the outworks. In 49 days the surrender took place, and six hundred regulars, thirteen hundred militia, and some thousands of the townsfolk were shippedback io France. Hannay says, apparently with some bitterness : "The news was received in Europe with incredulous surprise. Had such a deed of arms been done in Greece, two thousand years ago, the details would have been taught in the

schools generation after generation, great poets would have wedded them to immortal verse. But as the people who won this triumph were not Greeks or Romans, but only colonists, the affair was but the talk of a day, and most of the books called histories of England, ignore it altogether." The heroism was expended in vain, for in 1748, the colonists saw with feelings of indignation, the island of Cape Breton and the fortress of Louisburg, given back to France, to become once more their menace, and once more their prize.

During all this time the Acadians were accused of acting with duplicity, secretly furnishing aid to the French, and secretly stirring up the Indians. In the summer of 1749, when Halifax was founded, Governor Cornwallis plainly told them this, and that all must take a new oath of allegiance by the end of October. If not, they must leave the country, and leave their effects behind them. This was refused, and the relations between them rapidly became strained, even to the verge of belligerence. There is no doubt that La Loutre, the missionary before mentioned, who was at that time Vicar-General of Acadia, under the Bishop of Quebec, stirred up the Micmacs to revolt, and induced the Acadians to be obstinate.

By persuasion or threats he had already induced some two thousand Acadians to leave their homes and cross the boundary. This boundary was the Missiquash river; on its north side was the fort Beau Sejour, erected by the French; and there wereother forts with settlements about them at Baie Verte and St. John. Many were in a miserable condition, and wished to return to their lands, but would not take the proffered oath.* La Loutre lost no opportunities by sermons and emissaries to create ill will to the English garrisons at Minas, Piziquid, Chignecto and other places. The English complained that the Acadians were hostile in every sense, short of open rebellion,

"Je promets et Jure sincrement que je serai fid?le, et que je porteral une loyaut? parfaite vers sa Majest? George Second"

carrying their supplies of provisions across the Bay, and it even required a mandate from Halifax to induce them to sell wood to the English forts. Thus everything was ripe for war when war again began.

The commission to settle the limits of Acadia had failed, and both sides were preparing for the struggle. The English, as in 1745, were first ready to strike, and sailing from the same port of Boston, were as fortunate as before, for they succeeded in reducing the French forts at Beau S?jour, Baie Verte and St. John. In fact of the four expeditions of that year, (1755) this alone had a complete measure of success.

And now the expatriation of the Acadians was resolved on. That such an extreme measure was justifiable we can hardly believe Yet, much can be said in extenuation. It was at the beginning of a mortal and doubtful straggle between these two nations for the supremacy of a continent. Half way measures might mean ruin. The Acadians claimed to be regarded as neutrals, yet they had not remained so; positive proof existed of their aiding the French, and stirring up the savages to revolt and rapine. Allowed the free exercise of their faith, and any number of priests, till these were found acting as political agents, with no taxation but a tithe to their own clergy, they were growing rich, and were much better off in every way than their compatriots in France, and immeasurably more so than the wretched Canadians under the rapacious Bigot. British settlement had been retarded by their presence. Surely every government had the right to demand an unconditional oath of allegiance against all enemies whatsoever.

This was the burden of Gen, Lawrence's address to the protesting delegations from the various settlements. But as they still obstinately refused the oath, active measures were at once set on foot for their removal from the colony. Expeditions were sent out to burn houses and destroy all places of shelter. Resistance was not to be anticipated, as they had been deprived

of arms some time before, yet, at Chignecto and some otherplaces, they met with resistance, and suffered considerable loss from the French and Indians. On Minas Basin, Colonel Winslow had no opposition.

On Friday, the 5th September, all males of 10 years and up-wards were ordered to attend at the church in Grand-Pré. Over four hundred attended and remained prisoners till the time of embarkation. Vessels were collected from vadous quarters, and as much as possible of the people's household effects was taken, similar measures were taken at the other settlements, the troops employed doing the work of collecting the people, and embarking them aa quietly and tenderly as possible. Care was taken not to separate families, but some sad separations there must have been. They were taken to Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Virginia, Greorgia, the Carolinas, and the West Indies. The number is much disputed. Hannay, who sums up against the Acadians on most points, puts it at a little over three thousand, two-thirds of whom after a time returned. Bysome the number is put as high as eight thousand, of which three thousand only returned.*

ORIGIN OF THE POEM.

It was to Hawthorne that the poet was, indirectly at least, indebted for the subject. The circumstances under which it was suggested, and the preparation made for writing the poem, are thus told in Robertspn's Lift.

* Dr. Kingsford, in the 8rd vol. of his History of Canada, takes an even more decided position against the Acadians than Hannay, so that Longfellow's pictures of the people and of the priests as well, would seem utterly fictitious. He makes the most sweepins charges as to the politioal character and motives of the French priests, their never ending intrigues, and the instigation to outrage and massaore of the savages under their spiritual control. The Acadians are represented as anything but the peace-loving, religious, hospitable and brave people that our poet pictures. He shows clearly that the kings of France and the governors of Canada made use of La Loutre for their schemes and afterwards repudiated him.

Hawthorne one day dined at Craigie House, and brought with him a clergyman. The latter happened to remark that he had been vainly endeavoring to interest Hawthorne in a subjec that he himself thought would do admirably for a story. He then related the history of a young Acadian girl, who had been turned away with her people in that dire "'55," there-after became separated from her lover, wandered for many years in search of him, and finally found him in a hospital dying. 'Let me have it for a poem, then,' said Longfellow, and he had the leave at once. He raked up historical material from Haliburton's 'Nova Scotia,' and other books, and soon was steadily building up that idyl which is his true Oolden Legend. Beyond consulting records, he put together the material of Evangeline entirely out of his head ; that is to say, he did not think it necessary to visit Acadia and pick up local color. When a boy he had rambled about the old Wadsworth home at Hiram, climbing often to a balcony on the roof, and thence looking over great stretches of wood and hill; and from recollections of such a scene it was comparatively easy for him to imagine the forest primeval."

THE MEASURE OF EVANGILINE

is what is generally called dactylic hexameter. But as the number of accents and not the number of the syllables or the quantity of the vowels, is the true criterion for English verse, we may call it the hexameter verse of six accents, the feet being either dactyls or trochees. This measure has never become very popular with English poets. The cæsural pause is usually about the middle of the line, after the accented syllable of the 3rd or 4th foot In this measure a sing song monotony is the great evil to be guarded against, and Longfellow is very successful in avoiding an excess of it by dexterously shifting the place of the main verse pause. Trochees are inter-

changeable with dactyls, and occur very frequently everywhere,

but always conclude the line.

On' the | mor'row to | me'et in the | chu'rch || when hit | ma'jesty's | ma'ndate.

And a | no'n with his | wo'oden | shoes || beat | tim'e to the | mu'sic.

The following has been pointed out as a very perfect hexa.meter scansion :

Chanting the | Hundredth | Psalm—that | grand oLd | Puritan | Anthem.

And the following is almost comic in the violent wrench the scansion gives to the natural reading of the words :

Children's | children | sa't on his | kne'e || and | hea'rd his great |wa'tch tick.

We must be allowed to quote from the poet's most discriminating biographer; his remarks are so telling and to the point.

"The truth is that this measure, within its proper use, should be regarded not as a bastard classicism, but as a wholly modern invention. Impassioned speech more often breaks into pentameter and hexameter than into any other measure. Long-fellow himself has pointed to the splendid hexameters that abound in our Bible. 'Husbands love your wives, and be not bitter against them ;' 'God is gone up with a shout, the Lord with the sound of a trumpet.'" "Would Mr. Swinburne, simply because these are English hexameters, deny their lofty beauty? This form of verse will never, in all probability, become a favorite vehicle for poets' thoughts, but by a singular tour de force, Longfellow succeeded in getting rid of the popular prejudice against it, and whatever the classicists may say, he put more varied melody into his lines than Clough, Hawtrey, Kingsley, Howells or Bayard Taylor, attained in similar experiments. "—Robertson.

Longfellow, after much thought and some experiment, decided that this was the most fitting form, and we are now certain that his fine sense of harmony and form was not at fault. The har-

monious and slightly monotonous rise and fall of this uncommon but not un-English metre, is well adapted to convey that 'lingering melancholy' which pervades the tale, and that epic simplicity was in agreement with the supposed character of a people so far removed in time from us hard headed, unromantic,and therefore unattractive moderns.

Longfellow says, in his diary : "I tried a passage of it in the common rhymed English pentameter. It is the mocking-bird's song.

"Upon a spray, that overhang the stream, The mocking-bird, awaking from his dream, Poured such delicious music from his throat That all the air seemed listening to his note. Plaintive at first the song began and slow; It breathed of sadness, and of pain and woe; Then gathering all his notes, abroad he flung The multitudinous music from his tongue; As, after showers, a sudden gust again, Upon the leaves shakes down the rattling rain."

Now, let the student compare with this the lines of Evangeline,(part ii., 11. 208-217) and he will be satisfied, we think, that the latter ar preferable. The jingle of the rhyme and the shorter pulse of the line would have been less in agreement with that vein of protracted pathos and melancholy distinctive of the poem.

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE MAN AND OF HIS POETRY.

Longfellow was too broadly human to speak in the dogmatic manner of the creeds. His Unitarianism never peeps out. A poet's religion must of necessity be broad and tolerant, and Longfellow's, although truly Christian, was distinctly so. He was no controversialist or polemic; religion was with him amatter of the heart rather than of the head. The Roman Catholics are said to have at one time thought him tending in their direction; but the truth was simply this, that he was

easily led to commend whatever by its beauty or nobility gratified the artist instinct within him. In this way he was a religious eclectic. A child-like trust that God's way is the best, resignation to His will, and a resolve to do the duty that lies before him is the substance of Longfellow's moral philosophy. Lucifer, even,

. . . "Is God's minister. And labors for some good By us not understood."and again—

"What seem to us but sad, funereal tapers May be heaven's distant lamps."

Hope ever points the way, and should excite to action. His smaller pieces, such as The Psalm, Excelsior, and the Village Blacksmith, have been very successful, because they reflect the spirit of the Anglo-American race, their utilitarian and practical aims. To labor is our duty—success will be our reward. Do the duty that lies nearest you, and let there be no repining Act, act in the living present.

Some have sneered at these low ideals as poem-stuff; but the fact remains that these verses have become household words, and, although we are likely to be pitied for saying so, will perhaps be treasured when the flights of Shelley or the mysteries of Browning are forgotten or are still unintelligible.

Of dramatic power Longfellow had small share, for the absence of passion alone unfitted him for the inner conflict of the spirit His strength is in the portrayal of still life, i.e. external nature, or the comparatively uneventful and colorless course of domestic rural life. Of such he can see every minutest beauty, and from such extract every poetic grace.

In marking out a course for himself in the Prelude he lays:

"Look, then, into thy heart and write! Yes, into Life's deep stream!"

He never carried out his rule.It was not in his gentle, loving

nature to look on the seamy side of life. Of the "deepstream " he had little experience, and there are no great depths of sorrow or heights of joy in his life or writings. To the ear of this æsthetic litterateur this accomplished disciple (notapostle) of culture and beauty, their notes ever blend in harmony—

" I heard the sounds of sorrow and delight, The manifold, soft chimes.That filled the haunted chambers of the night, like some old poet's rhymes."

Love, as between the sexes, has scarcely any place in Longfellow's poetry, and of his smaller pieces not one is addressed to an individual in amatory and impassioned language. His conception of their relation is purely connubial—

" As unto the bow the cord is, So onto the man is woman; Though she bends him she obeys him. Though she draws him yet she foUows, Useless each without the other."

Malevolent humor forms a large portion of our dramatic literature, and Longfellow was by no means a good hater. In fact, he hated nobody and nothing. Added to all this, he was very deficient in the comie vein, and critics, with great unanimity, agree that of plot he had no just notion. Now, as we know that love, hate and jealousy, conjoined with planning, are main ingredients in the drama of life, and must be of the writing that mirrors it, we can easily see how Longfellow comes short of even moderate success in his dramatic efforts.

He shuts his eyes to the shadows of life ; he enjoins us to have a "heart for any fate," but he shrinks from picturing its stern and repulsive realities. Pope's sententious maxim, "Whatever is is best," is illustrated on almost every page. The devil himself we have seen to be Ood's minister; the rows of beds in the hospitals are an attractive object for him;

death is the " consoler and healer;" the grave is "a covered bridge leading from light to light." In his sermon-poems (and what restful, joyful sermons they are) we never hear of the gloomy doctrine of eternal punishment; it would seem quite foreign to the poet's creed.

In the imaginative faculty, that creative power that dis-tinguishes the poetry of, say Milton and Shelley, he was lacking, but in fertility of fancy he excels; he has always an eye and an ear for the suggestive side of a theme. It is almost a mannerism of his to compare an outward fact with an inward experience; hence his seeing and searching for similes with generally successful, but sometimes doubtful or weakening effect. This facile fancy of his had hosts of imitators, but they could not embellish it. with his tender and beautiful sayings, which have sunk so deeply into the hearts of the present generation.

He easily excels all poets of his day in the art of story-telling. His best stories are short enough to leave an impression of unity. Their brevity, their absence of intricate plots, the good judgment in the selection of subjects, the fitting verse-form and graceful treatment, have charmed a world of readers. He became very early aware that in this age of story-telling only the poetry that recounts will lastingly interest our boys and girls, and even our men and women. Consequently he strove to be interesting, and (as he himself confessed) to the people.

"In England Longfellow has been called the poet of the middle classes. Those classes include, however, the majority of intelligent readers, and Tennyson had an equal share of their favor. The English middle class form an analogue to the one great class of American readers. Would not any poet whose work might lack the subtlety that commends itself to professional readers be relegated by University critics to the middle-class wards? Caste and literary priesthood have ?ome

thing tc do with this. This point taken with regard to Longfellow is not unjust. So far as comfort, virtue, domestic tenderness, and freedom from extremes of passion and incident are characteristic of the middle classes, he has been their minstrel."As Mr. Stedman hints, in writing the above, the poetry whose melody and range of thought appeal to one and all has out-lasted, and will outlast, most of the poetry that requires a commentary.

Longfellow has been accused (by Poe especially) of being a plagiarist. It is true that he had but little invention, but we know that even the fields of invention have been pretty well ploughed over, and the greatest poets may be excused for borrowing theme and incident, if they transmute them into their own manner, clothe them in new language, and adorn them with new fancy. In this sense Longfellow was as original as most of his guild, and it must be confessed that he, in turn, has been freely drawn upon by others.

ELEMENTS AND QUALITIES OF STYLE.

Two characteristics of Longfellow are clearness and simplicity, alike in the vocabulary and the structure. It is true he is not so exclusively Saxon or monosyllabic in his language, but the metre chosen for Evangeline forced him somewhat to dissyllables and trisyllables. The structural simplicity is more marked than the verbal simplicity, agreeing perfectly with the laws of narrative. As a rule, only the simplest inversions occur, and there are probably not half a dozen instances in all the selections in which the construction is not at once apparent.In figures of speech, especially the simile, he is sometimes not very clear, i.e. the reader does not at once catch the likeness.To this attention has been frequently drawn in the notes. Another point should be noticed, that he is never obscure, either from excessive brevity and condensation, as Byron often

is, or from involved complex sentences. But we should say that he must frequently be obscure to many, owing to his too remote or out of the way allusions.

Picturesqueness is the middle ground between the intellectual and the emotional qualities of style, i.e. it asists the understanding, and, at the same time, it operates on the feelings. It is a fairly strong point with Longfellow. He makes large use of similitude. So fond, indeed, is he of comparisons for wayside flowers to adorn his narrative that the resemblance oftenturns upon something not sufficiently relevant to the circumstances. He makes far greater use of simile than of metaphor, to which fact is very largely owing his lack of strength. These figures are oftener, too, on the intellectual side than on the emotional side, which accounts for the criticism generally made upon him, that in vividness and strength of color he occupies but a middle place. As might be expected when such a verdict is given, transferred and single epithets are less common than phrasal and appended ones.

His strongest point is harmony. Rarely does he choose ametre ill-fitting his theme; and the critical world seems coming round to the belief that the metre of Evangeline is, after all, eminently suitable to this idyl of a primitive people. Alliteration, both open and veiled, is common with him. He is frequently imitative of sounds and onomatopoetic: favorable to words with liquid letters, and avoids harsh combinations of consonants, as, for instance, a clashing of mutes.

He is deficient in impressiveness and energy, making little use of the figures of contrast, and in general of the epigrammatic or pointed style. From the nature of his poetry, mainly narrative, he can make but little use of interrogation and climax. In Evangeline the monotony of the line was no doubt some hindrance. But the main reasons are no doubt connected with the emotional qualities of his style. Malevolence and strong passion of any kind, and action depending thereon, are

seldom found in his poetry; the pathetic and the persuasive are more in consonance with even flow and melody of language.

OPINIONS AHD QUESTIONS.

Everything suggested an image to him. and the imagery sometimes reacted and suggested a new thought. Thus, in Evangeline,

"Bent like a laboring oar that toils in the surf of the ocean "

is not a good comparison, as it suggests turmoil foreign to the life of the notary and the Acadians generally, but it suggests a new line, which somewhat restores the idea of still continuing virility—

"Bent, but not broken, by age was the form of the notary public."

"Evangeline is already a little classic, and will remain one as surely as the Vicar of Wakefield the Deserted Village, or any other sweet and pious idyl of the English tongue. There areflaws, and petty fancies, and homely passages, but it is thus far the flower of American idyls.—Stedman.

There is great disagreement among literary men not so much in their general estimate of his range and power as in regard to the order of excellency of his different poems. The following questions are taken, some from examination papers, and a few from Mr. Grannett's Outlines for the Study of Longfellow

(Houghton, Mifflin & Co.):

(1) Should you call him self-revealing or self-hiding in his poems?

(2) Which are the prettiest of the village scenes in Evangeline, in doors and out of doors?

(3 Who besides Longfellow has used the hexameter? Is it right to call it an un-English metre ?

(4) Is Evangeline an epic, an idyl or a tragedy? Give your reasons.

(5) Is the maiden strongly outlined in person and in character? Point out the lines that best describe each.

(6) Which are the finest landscapes in Evangeline. Does he picture nature vividly, and to give it expression or impiession?

(7) Mention lines that justify the appellations given to himof poet of the afiections, of the night, of the sea.

(8) Can you discover the American, the Puritan, the scholar in these selections? Where?

(9) He is said to be "intensely national" and of " universal nationality." Are these contradictory?

(10) Mention the poems which are most American in incident and in spirit.

"Much of his time and talent was devoted to reproducing in English the work of foreign authors. In the smaller pieces his talent is most conspicuous, for in them sentiment is condensed into a few stanzas. His copious vocabulary, his sense for the value of words, his ear for rhythm, fitted him in a peculiar degree to pour fancy from one vessel into another."—Frothingham.

"Longfellow had not Bryant's depth of feeling for ancient history or external nature. Morality to Emerson was the very breath of existence; to Longfellow it was a sentiment. Poe's best poetic efforts are evidence of an imagination more self-sufficient than Longfellow's was. In the best of Whittier's poems, the pulse of human sympathy beats more strongly than in any of our poet's songs. Still more unlike his sentimentality is the universal range of Whitman's manly outspoken kinsmanship with all living things. How then has he out distanced these men so easily! By virtue of his artistic eclecticism."—Robertson.

The full answer as given by Robertson may be summed up as follows :—He had more variety than Bryant, in measure and choioe of subject; his humanitariauism is not pitched too high for common peoplo to grasp, aa Emerson's often is; he was a

man of more moral principle and common sense than Poe; beauty and moral goodness went together with Longfellow; by reason of his culture and learning he appealed to wider audiences than Whittier; and lastly his poetry is wholly free from the grosaness of Whitman, and, while as easily understood by the many, is at the same time more attractive in form and treatment.

(1) Has Longfellow a deep sense of the mystery of nature, or any sense of it as hate? Point out some passages of trust and worship.

(2) Would you from your list of selections call him a religious poet? a moral poet ?

(3) Which of bis poems have "man" in thought? Is the effect of his poetry as here given active or passive, restful or stirring, to teach duty or simply to give pleasure? Distinguish the passages.

CHARACTERISTICS OF POETIC DICTION.*

1. It is archaic and non-colloquiaL

(a) Poetry, being less conversational than prose, is less affected by the changes of a living tongue, and more influenced by the language and traditions of the poetry of past ages.

(b) Not all words are adapted for metre.

(c) Certain words and forms of expression being repeated by successive poets acquire poetic associations, and become part ofthe common inheritance of poets.

2. It is more picturesque than prose.

(a) It prefers specific, concrete, and virid terms to generic, abstract, and vague ones.

(b) It often uses words in a sense different from their ordinary meaning.

*See Genung's Rhetoric, pp. 48-68.

(e) It often substitutes an epithet for the thing denoted.

Note.—Distinguish between ornamental epithets, added to give color, interest and life to the picture, and essential epithets, necessary to convey the proper meaning.

3. It is averse to lengthiness.

(a) It omits conjunctions, relative pronouns and auxiliaries, and makes free use of absolute and participial constructions.

{b) It substitutes epithets and compounds for phrases and clauses.

(c) It makes a free use of ellipsis.

(d) It avoids long common-place worda

Note.—Sometimes, however, for euphony, euphemism, or pictures-queness it substitutes a periphrasis for a word.

4. It pays more regard to euphony than prose does.

5. It allows inversions and constructions not used in prose.

6. It employs figures of speech much more freely than prose.

Qualities of Style.

1. Intellectual, including Clearness (opposed to Obscurity and Ambiguity), Simplicity (opposed to Abstruseness), Impressiveness and Picturesqueness.

2. Emotional, including Strength (Force), Feeling (Pathos), the Ludicrous (Wit, Humor and Satire).

3. Æsthetic, including Melody, Harmony (of Sound and Sense), Taste.

EVANGELINE.

A TALE OF ACADIE.

1847.

PREFATORY NOTE.

The story of "EVANGELINE" is founded on a painful occurrence which took place in the early period of British colonization in the northern part of America.

In the year 1713, Acadia, or, as it is now named. Nova Scotia, was ceded to Great Britain by the French. The wishes of the inhabitants seem to have been little consulted in the change, and they with great difficulty were induced to take the oaths of allegiance to the British Government. Some time after this, war having again broken out between the French and British in Canada, the Acadians were accused of having assisted the French, from whom they were descended, and connected by maay ties of friendship, with provisions and ammunition, at the siege of Beau Séjour. Whether the accusation was founded on fact or not, has not been satisfactorily ascertained; the result, however, was most disastrous to the primitive, simple-minded Acadians. The British Government ordered them to be removed from their homes, and dispersed throughout the other colonies, at a distance from their much-loved land. This resolution was not communicated to the inhabitants till measures had been matured to carry it into immediate effect; when the Governor of the colony, having issued a summons calling the whole people to a meeting, informed them that their lands, tenements, and cattle of all kinds were forfeited to the British crown, that he had orders to remove them in vessels to distant colonies, and they must remain in custody till their embarkation.

The poem is descriptive of the fate of some of the persons involved in these calamitous proceedings.

INTRODUCTION

THIS is the forest primeval. The murmuring pines and the hemlocks,

Bearded with moss, and in garments green, indistinct in the twilight,

Stand like Druids of eld, with voices sad and prophetic,

Stand like harpers hoar, with beards that rest on their bosoms.

Loud from its rocky caverns, the deep-voiced neighboring ocean

Speaks, and in accents disconsolate answers the wail of the

forest.

This is the forest primeval; but where are the hearts that beneath it

Leaped like the roe, when he hears in the woodland the voice of the huntsman?

Where is the thatch-roofed village, the home of Acadian farmers, —

Men whose lives glided on like rivers that water the woodlands,

Darkened by shadows of earth, but reflecting an image of heaven?

Waste are those pleasant farms, and the farmers forever departed!

Scattered like dust and leaves, when the mighty blasts of October

Seize them, and whirl them aloft, and sprinkle them far o’er the ocean.

Naught but tradition remains of the beautiful village of Grand-Pré.

Ye who believe in affection that hopes, and endures, and is patient,

Ye who believe in the beauty and strength of woman’s devotion,

List to the mournful tradition still sung by the pines of the forest;

List to a Tale of Love in Acadie, home of the happy.

I.

IN the Acadian land, on the shores of the Basin of Minas,

Distant, secluded, still, the little village of Grand-Pré

Lay in the fruitful valley. Vast meadows stretched to the eastward,

Giving the village its name, and pasture to flocks without number.

Dikes, that the hands of the farmers had raised with labor incessant,

Shut out the turbulent tides; but at stated seasons the flood-gates

Opened, and welcomed the sea to wander at will o’er the meadows.

West and south there were fields of flax, and orchards and cornfields

Spreading afar and unfenced o’er the plain; and away to the northward

Blomidon rose, and the forests old, and aloft on the mountains

Sea-fogs pitched their tents, and mists from the mighty Atlantic

Looked on the happy valley, but ne’er from their station descended.

There, in the midst of its farms, reposed the Acadian village.

Strongly built were the houses, with frames of oak and of chestnut,

Such as the peasants of Normandy built in the reign of the Henries.

Thatched were the roofs, with dormer-windows; and gables projecting

Over the basement below protected and shaded the door-way.

There in the tranquil evenings of summer, when brightly the sunset

Lighted the village street, and gilded the vanes on the chimneys,

Matrons and maidens sat in snow-white caps and in kirtles

Scarlet and blue and green, with distaffs spinning the golden

Flax for the gossiping looms, whose noisy shuttles within doors

Mingled their sound with the whir of the wheels and the songs of the maidens.

Solemnly down the street came the parish priest, and the children

Paused in their play to kiss the hand he extended to bless them.

Reverend walked he among them; and up rose matrons and maidens,

Hailing his slow approach with words of affectionate welcome.

Then came the laborers home from the field, and serenely the sun sank

Down to his rest, and twilight prevailed. Anon from the belfry

Softly the Angelus sounded, and over the roofs of the village

Columns of pale blue smoke, like clouds of incense ascending,

Rose from a hundred hearths, the homes of peace and contentment.

Thus dwelt together in love these simple Acadian farmers, —

Dwelt in the love of God and of man. Alike were they free from

Fear, that reigns with the tyrant, and envy, the vice of republics.

Neither locks had they to their doors, nor bars to their windows;

But their dwellings were open as day and the hearts of the owners;

There the richest was poor, and the poorest lived in abundance.

Somewhat apart from the village, and nearer the Basin of Minas,

Benedict Bellefontaine, the wealthiest farmer of Grand-Pré,

Dwelt on his goodly acres; and with him, directing his household,

Gentle Evangeline lived, his child, and the pride of the village.

Stalworth and stately in form was the man of seventy winters;

Hearty and hale was he, an oak that is covered with snow-flakes;

White as the snow were his locks, and his cheeks as brown as the oak-leaves.

Fair was she to behold, that maiden of seventeen summers.

Black were her eyes as the berry that grows on the thorn by the wayside,

Black, yet how softly they gleamed beneath the brown shade of her tresses!

Sweet was her breath as the breath of kine that feed in the meadows.

When in the harvest heat she bore to the reapers at noontide

Flagons of home-brewed ale, ah! fair in sooth was the maiden.

Fairer was she when, on Sunday morn, while the bell from its turret

Sprinkled with holy sounds the air, as the priest with his hyssop

Sprinkles the congregation, and scatters blessings upon them,

Down the long street she passed, with her chaplet of beads and her missal,

Wearing her Norman cap, and her kirtle of blue, and the ear-rings,

Brought in the olden time from France, and since, as an heirloom,

Handed down from mother to child, through long generations.

But a celestial brightness — a more ethereal beauty —

Shone on her face and encircled her form, when, after confession,

Homeward serenely she walked with God’s benediction upon her.

When she had passed, it seemed like the ceasing of exquisite music.

Firmly builded with rafters of oak, the house of the farmer

Stood on the side of a hill commanding the sea; and a shady

Sycamore grew by the door, with a woodbine wreathing around it.

Rudely carved was the porch, with seats beneath; and a footpath

Led through an orchard wide, and disappeared in the meadow.

Under the sycamore-tree were hives overhung by a penthouse,

Such as the traveller sees in regions remote by the roadside,

Built o’er a box for the poor, or the blessed image of Mary.

Farther down, on the slope of the hill, was the well with its moss-grown

Bucket, fastened with iron, and near it a trough for the horses.

Shielding the house from storms, on the north, were the barns and the farm-yard,

There stood the broad-wheeled wains and the antique ploughs and the harrows;

There were the folds for the sheep; and there, in his feathered seraglio,

Strutted the lordly turkey, and crowed the cock, with the selfsame

Voice that in ages of old had startled the penitent Peter.

Bursting with hay were the barns, themselves a village. In each one

Far o’er the gable projected a roof of thatch; and a staircase,

Under the sheltering eaves, led up to the odorous corn-loft.

There too the dove-cot stood, with its meek and innocent inmates

Murmuring ever of love; while above in the variant breezes

Numberless noisy weathercocks rattled and sang of mutation.

Thus, at peace with God and the world, the farmer of Grand-Pré

Lived on his sunny farm, and Evangeline governed his household.

Many a youth, as he knelt in the church and opened his missal,

Fixed his eyes upon her, as the saint of his deepest devotion;

Happy was he who might touch her hand or the hem of her garment!

Many a suitor came to her door, by the darkness befriended,

And, as he knocked and waited to hear the sound of her footsteps,

Knew not which beat the louder, his heart or the knocker of iron;

Or at the joyous feast of the Patron Saint of the village,

Bolder grew, and pressed her hand in the dance as he whispered

Hurried words of love, that seemed a part of the music.

But, among all who came, young Gabriel only was welcome;

Gabriel Lajeunesse, the son of Basil the blacksmith,

Who was a mighty man in the village, and honored of all men;

For, since the birth of time, throughout all ages and nations,

Has the craft of the smith been held in repute by the people.

Basil was Benedict’s friend. Their children from earliest childhood

Grew up together as brother and sister; and Father Felician,

Priest and pedagogue both in the village, had taught them their letters

Out of the selfsame book, with the hymns of the church and the plain-song.

But when the hymn was sung, and the daily lesson completed,

Swiftly they hurried away to the forge of Basil the blacksmith.

There at the door they stood, with wondering eyes to behold him

Take in his leathern lap the hoof of the horse as a plaything,

Nailing the shoe in its place; while near him the tire of the cart-wheel

Lay like a fiery snake, coiled round in a circle of cinders.

Oft on autumnal eves, when without in the gathering darkness

Bursting with light seemed the smithy, through every cranny and crevice,

Warm by the forge within they watched the laboring bellows,

And as its panting ceased, and the sparks expired in the ashes,

Merrily laughed, and said they were nuns going into the chapel.

Oft on sledges in winter, as swift as the swoop of the eagle,

Down the hillside bounding, they glided away o’er the meadow.

Oft in the barns they climbed to the populous nests on the rafters,

Seeking with eager eyes that wondrous stone, which the swallow

Brings from the shore of the sea to restore the sight of its fledglings;

Lucky was he who found that stone in the nest of the swallow!

Thus passed a few swift years, and they no longer were children.

He was a valiant youth, and his face, like the face of the morning,

Gladdened the earth with its light, and ripened through into action.

She was a woman now, with the heart and hopes of a woman.

“Sunshine of Saint Eulalie” was she called; for that was the sunshine

Which, as the farmers believed, would load their orchards with apples;

She, too, would bring to her husband’s house delight and abundance,

Filling it full of love and the ruddy faces of children.

II.

NOW had the season returned, when the nights grow colder and longer,

And the retreating sun the sign of the Scorpion enters.

Birds of passage sailed through the leaden air, from the ice-bound,

Desolate northern bays to the shores of tropical islands.

Harvests were gathered in; and wild with the winds of September

Wrestled the trees of the forest, as Jacob of old with the angel.

All the signs foretold a winter long and inclement.

Bees, with prophetic instinct of want, had hoarded their honey

Till the hives overflowed; and the Indian hunters asserted

Cold would the winter be, for thick was the fur of the foxes.

Such was the advent of autumn. Then followed that beautiful season,

Called by the pious Acadian peasants the Summer of All-Saints!

Filled was the air with a dreamy and magical light; and the landscape

Lay as if new-created in all the freshness of childhood.

Peace seemed to reign upon earth, and the restless heart of the ocean

Was for a moment consoled. All sounds were in harmony blended.

Voices of children at play, the crowing of cocks in the farm-yards,

Whir of wings in the drowsy air, and the cooing of pigeons,

All were subdued and low as the murmurs of love, and the great sun

Looked with the eye of love through the golden vapors around him;

While arrayed in its robes of russet and scarlet and yellow,

Bright with the sheen of the dew, each glittering tree of the forest

Flashed like the plane-tree the Persian adorned with mantles and jewels.

Now recommenced the reign of rest and affection and stillness.

Day with its burden and heat had departed, and twilight descending

Brought back the evening star to the sky, and the herds to the homestead.

Pawing the ground they came, and resting their necks on each other,

And with their nostrils distended inhaling the freshness of evening.

Foremost, bearing the bell, Evangeline’s beautiful heifer,

Proud of her snow-white hide, and the ribbon that waved from her collar,

Quietly paced and slow, as if conscious of human affection.

Then came the shepherd back with his bleating flocks from the seaside,

Where was their favorite pasture. Behind them followed the watch-dog,

Patient, full of importance, and grand in the pride of his instinct,

Walking from side to side with a lordly air, and superbly

Waving his bushy tail, and urging forward the stragglers;

Regent of flocks was he when the shepherd slept; their protector,

When from the forest at night, through the starry silence, the wolves howled.

Late, with the rising moon, returned the wains from the marshes,

Laden with briny hay, that filled the air with its odor.

Cheerily neighed the steeds, with dew on their manes and their fetlocks,

While aloft on their shoulders the wooden and ponderous saddles,

Painted with brilliant dyes, and adorned with tassels of crimson,

Nodded in bright array, like hollyhocks heavy with blossoms.

Patiently stood the cows meanwhile, and yielded their udders

Unto the milkmaid’s hand; whilst loud and in regular cadence

Into the sounding pails the foaming streamlets descended.

Lowing of cattle and peals of laughter were heard in the farm-yard,

Echoed back by the barns. Anon they sank into stillness;

Heavily closed, with a jarring sound, the valves of the barn-doors,

Rattled the wooden bars, and all for a season was silent.

In-doors, warm by the wide-mouthed fireplace, idly the farmer