George Washington Cable.

“Posson Jone.”

notes to next group

- we combined 1 and 2 and proofread them the rest of the files need to be imported and proofread.

Part 1: Introduction

As we commemorate its bicentennial, the famous Lewis and Clark Expedition evokes pride and awe in countless Americans who reflect upon its achievements. Its dynamism and sweep carried American explorers across the breadth of a vast continent for the first time. Its scientific agenda brought back invaluable information about flora, fauna, hydrology, and geography. Its benign intent established fruitful trade relations and encouraged peaceable commerce with Native Americans encountered en route. The Expedition was, all things considered, a magnificent example of our young nation�s potential for progress and creative good.

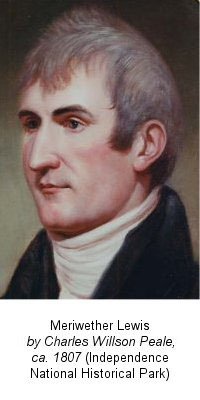

While most Americans have some inkling of the importance of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, relatively few recognize that it was an Army endeavor from beginning to end, officially characterized as the “Corps of Volunteers for North Western Discovery.” It is no accident that the new nation and its president, Thomas Jefferson, turned to the Army for this most important mission. Soldiers possessed the toughness, teamwork, discipline, and training appropriate to the rigors they would face. The Army had a nationwide organization even in that early era and thus the potential to provide requisite operational and logistical support. Perhaps most important, the Army was already in the habit of developing leaders of character and vision; Meriwether Lewis, William Clark, and the outstanding noncommissioned officers who served with them being cases in point.

This brochure was prepared in the U.S. Army Center of Military History by David W. Hogan, Jr., and Charles E. White. We truly hope you will enjoy this brief and engaging account of a stirring and significant event in our American military heritage.

JOHN S. BROWN

Brigadier General, USA

Chief of Military History

Part 2: President Jefferson's Vision

Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration of Independence and third president of the United States, did much to help create the new nation. Perhaps his greatest contribution was his vision. Even before he became president, Jefferson dreamed of a republic that spread liberty and representative government from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean. As one of the leading scientific thinkers of his day, he was curious about the terrain, plant and animal life, and Indian tribes of the vast, unknown lands west of the Mississippi River. As a national leader, he was interested in the possibilities of agriculture and trade in those regions and suspicious of British, French, Spanish, and Russian designs on them.

On 18 January 1803, months before President Jefferson had acquired the region from France through the famous Louisiana Purchase, he sent a confidential letter to Congress, requesting money for an overland expedition to the Pacific Ocean. Hoping to find the Northwest Passage, Jefferson informed Congress that the explorers would establish friendly relations with the Indians of the Missouri River Valley, help the American fur trade expand into the area, and gather data on the region�s geography, inhabitants, flora, and fauna.

the pics are in the DONE folder

To

conduct the expedition, Jefferson turned to the U.S. Army. Only the

military possessed the organization and logistics, the toughness and

training, and the discipline and teamwork necessary to handle the combination

of rugged terrain, harsh climate, and potential hostility of the endeavor.

The Army also embodied the American government�s authority in a

way that civilians could not. Indeed, the Army provided Jefferson with

a readily available, nationwide organization that could support the

expedition � no small consideration in an era when few national

institutions existed. Although the expedition lay outside the Army�s

usual role of fighting wars, Jefferson firmly believed that in time

of peace the Army�s mission went beyond defense to include building

the nation. Finally, the man that Jefferson wanted to lead the expedition

was an Army officer: his personal secretary, Capt. Meriwether Lewis.

To

conduct the expedition, Jefferson turned to the U.S. Army. Only the

military possessed the organization and logistics, the toughness and

training, and the discipline and teamwork necessary to handle the combination

of rugged terrain, harsh climate, and potential hostility of the endeavor.

The Army also embodied the American government�s authority in a

way that civilians could not. Indeed, the Army provided Jefferson with

a readily available, nationwide organization that could support the

expedition � no small consideration in an era when few national

institutions existed. Although the expedition lay outside the Army�s

usual role of fighting wars, Jefferson firmly believed that in time

of peace the Army�s mission went beyond defense to include building

the nation. Finally, the man that Jefferson wanted to lead the expedition

was an Army officer: his personal secretary, Capt. Meriwether Lewis.

A friend and neighbor of Jefferson�s, the 28-year-old Lewis had joined the Virginia militia to help quell the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794 and then had served for eight years as an infantry officer and paymaster in the Regular Army. In Lewis, Jefferson believed he had an individual who combined the necessary leadership ability and woodland skills with the potential to be an observer of natural phenomena.

Part 3: Preparations

Army to provide transportation for his nearly four tons of supplies

and equipment from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh. Lewis then set off for

Washington for a final coordination meeting with President Jefferson.

Army to provide transportation for his nearly four tons of supplies

and equipment from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh. Lewis then set off for

Washington for a final coordination meeting with President Jefferson.